Yasumasa Morimura Theater of the Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yasumasa Morimura

YASUMASA MORIMURA BORN: 1951, Osaka, Japan. Lives in Osaka. 1978 B.A. Graduated from Kyoto City University of Art AWARDS The International Research Center for the Arts, Kyoto, artist-in-residence Fellow SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2007 “Yasumasa Morimura: Reflections,” John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI. 2006 “An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo,” Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Inc., Moscow, Russia (catalogue) 2005 "One Artist's Theater," Gary Tatintsian Gallery, Moscow, Russia “Los Nuevos Caprichos,” Galerie Taddeus Ropac, Paris, France Galeria Juana De Aizpuru, Madrid, Spain “Los Nuevos Caprichos,” Luhring Augustine, New York “Los Nuevos Caprichos,” SHUGOARTS, Tokyo, Japan 2003 “Barco Negro on the table”, MEM, Osaka “The Artist’s Treasures” Shugoarts, Tokyo “Polyhedron of Yasumasa Morimura / Kalei de Scope” B Gallery, Osaka Seikei University 2002 “Yasumasa Morimura” Galeria Juana de Aizpuru, Madrid “A Story of M’s Self-Portraits” Kawasaki City Museum, Kawasaki “A Photographic Show of Murmur and Hum” Bunkamura Gallery, Tokyo “Inside the Studio, Yasumasa Morimura,” Japan Society, New York (talk) SITE SantaFe, Santa Fe, New Mexico “Self-Portraits”, Ca di Fa, Milan, Italy “An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo (Self-Portraits), Gallery Juana de Aizpuru, Madrid, Spain 2001 “Story of M’s Portrait” Museum Eki, Kyoto “Self-Portraits: An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo,” Luhring Augustine, New York “Self-Portraits: An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo,” Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris, France “Gallery Talk,” Hammond Museum & Japanese Stroll Garden, North -

THE WARHOL EFFECT a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty

THE WARHOL EFFECT A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Joshua L. Morgan May, 2015 THE WARHOL EFFECT Joshua L. Morgan Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Interim School Director Mr. Neil Sapienza Mr. Neil Sapienza _______________________ _______________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Mr. Durand L Pope Dr. Chand Midha _______________________ _______________________ Committee Member Interim Dean of the Graduate School. Ms. Sherry Simms Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________ _______________________ Committee Member Date Mr. Charles Beneke ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES..………………………………………………………………...iv CHAPTERS I. MODERN DAY WARHOL...….…...……………………………………….…….1 II. ANDREW WARHOLA……..……………………………………………….……6 Early Life...……………..…………….........…………………………………6 Personal Life……………………………………………………………..…...8 III. THE ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS.…...…....13 IV. THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM….....……………………………………....15 V. GENESIS BREYER P’ORRIDGE..……………………….…………………...18 VI. DEBORAH KASS…………………………………….………………………...23 VII. YASUMASA MORIMURA…………………….……………………………..31 VIII. THE WARHOL EFFECT.…………………………………………………….34 BIBLIOGRAPHY.……………………………………………………………….….35 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 5.1 English Breakfast, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, 2009…………………..…...19 5.2 Amnion Folds, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, 2003………………………….. 22 6.1 Superman, Andy Warhol, 1961….…………………………………………24 6.2 Puff -

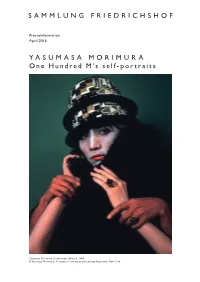

Yasumasa Morimura One Hundred M's Self-Portraits

SAMMLUNG FRIEDRICHSHOF Presseinformation April 2016 YASUMASA MORIMURA One Hundred M’s self-portraits Yasumasa Morimura, Doublonnage (Marcel), 1988 © Yasumasa Morimura; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York SAMMLUNG FRIEDRICHSHOF YASUMASA MORIMURA One Hundred M’s self-portraits Eröffnung Samstag, 30. 04. 2016 18.00 – 21.00 Einführende Worte Dr. Hubert Klocker (Direktor Sammlung Friedrichshof) Ort SAMMLUNG FRIEDRICHSHOF Römerstraße 7, 2424 Zurndorf, Burgenland Ausstellungsdauer 01. 05. 2016 – 20. 11. 2016 Der Künstler wird zur Finissage anwesend sein. Öffnungszeiten nach telefonischer Voranmeldung unter +43 (0) 676 7497682 www.sammlungfriedrichshof.at Die Ausstellung am Friedrichshof wird durch die Präsentation von Referenzwerken in der Wiener Dependance STADTRAUM ab 03. 05. 2016 begleitet. Druckfähiges Bildmaterial sowie Texte zur Arbeit Yasumasa Morimuras stehen auf unserer Homepage www.sammlungfriedrichshof.at unter Presseservice / Yasumasa Morimura zum Download bereit. Sollten Sie im Vorfeld bereits Bildmaterial benötigen, kontaktieren Sie uns gerne. Für nähere Auskünfte, Besichtigungstermine oder für die Organisation eines Interviews mit dem Künstler wenden Sie sich bitte an Marie Oucherif, [email protected] Die SAMMLUNG FRIEDRICHSHOF zeigt in den von Adolf Krischanitz ausgebauten Ausstellungsräumen ab April 2016 eine Neuhängung der Sammlungsbestände des Wiener Aktionismus mit Schwerpunkt auf Film. Dieser Präsentation werden einmal jährlich ausgewählte Positionen der Gegenwartskunst gegen- übergestellt. Wir -

Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura, Tokyo 2020 January 25 (Saturday) – June 7 (Sunday), 2020

2020/03/27 Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura, Tokyo 2020 January 25 (Saturday) – June 7 (Sunday), 2020 [1] No matter how deeply I searched within myself, I could never find anything resembling a center, much less any kind of truth. From the time I was a child, the only thing I knew for sure was that there was a vast emptiness there. If anything, things like truth, values and ideas, existed outside my body, and like clothes, I was free to change them whenever I liked. This concept made a lot more sense to me than anything else. from Ego Obscura The Hara Museum of Contemporary Art is proud to present Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura, Tokyo 2020. In his acclaimed photographic self-portraits, Morimura re-enacts famous paintings, movies and moments in history, injecting himself as the protagonist. By reincarnating himself through the skillful use of makeup and costume, he transcends the time, race and gender of the subject while imbuing it with a meta-commentary uniquely his own. Making a splash in 1985 with his debut work Portrait (Van Gogh), Morimura has persistently explored the theme of the "self" through his photographic works, and more recently through self-produced, -scripted and -acted video works and live performances. This exhibition comes on the heels of Morimura's highly successful Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura held last year at the Japan Society in New York. For this Tokyo version, he has rearranged his video work entitled Ego Obscura, which, along with a lecture performance, comprises the centerpiece of the show. In the video, Morimura appears as Emperor Hirohito, General Douglas MacArthur, Marilyn Monroe and Yukio Mishima – iconic figures that are deeply etched into the collective memory of the Japanese people. -

Las Meninas Reborn in the Night) December 13, 2014 – January 24, 2015 Opening Reception: Friday, December 12, 6 - 8Pm

Yasumasa Morimura Las Meninas Renacen de Noche (Las Meninas Reborn in the Night) December 13, 2014 – January 24, 2015 Opening Reception: Friday, December 12, 6 - 8pm Luhring Augustine is pleased to present Las Meninas Renacen de Noche (Las Meninas Reborn in the Night), a recent body of photographs by Yasumasa Morimura. In these self-portraits, the artist reimagines Diego Velázquez’s 1656 Las Meninas by assuming the role of each character in the renowned work. Morimura photographed Velázquez’s painting in situ at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, using the museum as a stage for his study. In his exploration of Las Meninas, Morimura creates new narratives by altering the positioning of the subjects both in the original composition and in the visual space of the museum. The artist first used imagery from Velázquez in 1990, when he impersonated Princess Margarita, or “The Infanta,” a portrait that appears in one photograph from this new series. In addition to the eleven personalities he assumes from Las Meninas, for the first time Morimura portrays himself, undisguised, as the artist. In his reconsideration of this iconic painting, Morimura further investigates the questions that Velázquez posed in regard to perspective, authorship, and identity. Morimura has been working as a conceptual photographer and filmmaker for more than three decades. Through extensive use of props, costumes, makeup, and digital manipulation, the artist masterfully transforms himself into recognizable subjects, often from the Western cultural canon. Morimura has based works on seminal paintings by Édouard Manet, Frida Kahlo, Vincent Van Gogh, and he also uses images culled from historical materials, mass media, and popular culture in his practice. -

IN the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the SECOND CIRCUIT the ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION for the VISUAL ARTS, INC., Plaintiff-Cou

Case 19-2420, Document 257, 05/03/2021, 3091950, Page1 of 30 19-2420 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT THE ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS, INC., Plaintiff-Counter-Defendant-Appellee, v. LYNN GOLDSMITH, LYNN GOLDSMITH, LTD., Defendants-Counter-Plaintiffs-Appellants. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York No. 17-cv-2532 (Hon. John G. Koeltl) CORRECTED BRIEF OF THE ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG FOUNDATION, ROY LICHTENSTEIN FOUNDATION, WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART, MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, AND THE SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEE’S PETITION FOR PANEL REHEARING AND REHEARING EN BANC Jaime A. Santos Andrew Kim GOODWIN PROCTER LLP 1900 N Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 346-4000 [email protected] [email protected] April 30, 2021 (corrected May 3, 2021) Counsel for Amici Curiae Case 19-2420, Document 257, 05/03/2021, 3091950, Page2 of 30 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE ......................................................................1 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................2 Artists Have Long Used Other Artists’ Work as “Raw Material” to Inspire the Creation of New Works Embedded with New Meaning. ................. 2 The Panel’s Erroneous Decision Will Have An Enormous Chilling Effect on Artists, -

How Do I Look: Identity and Photography in the Work of Nikki S

HOW DO I LOOK: IDENTITY AND PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE WORK OF NIKKI S. LEE by MATTHEW R. MCKINNEY (Under the Direction of Isabelle Wallace) ABSTRACT Often associated with self-revelation and truth, the self portraits of contemporary Korean photographer Nikki S. Lee sit uncomfortably within this genre and raise several interesting questions: What is a performance and what is real? If Lee is acting, what about the other participants in these snapshots? And most urgently, who is Nikki Lee? Throughout the entirety of Lee’s oeuvre, a body of work which includes both the Projects and Parts series as well as her upcoming film a.k.a. Nikki S. Lee , Lee destabilizes any preconceptions of a fixed self by appearing camouflaged, shifting her costume, mannerisms and props to assimilate to each subculture. This thesis, by providing a comprehensive account of Nikki Lee’s photography, will examine Lee’s fascination with the constructed nature of identity, and will consider how her work also prompts an interrogation of photography and its conventional association with truth and authenticity. INDEX WORDS: Nikki S. Lee, Photography, Snapshot, Identity, Masquerade, Projects Series, Parts Series HOW DO I LOOK: IDENTITY AND PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE WORK OF NIKKI S. LEE by MATTHEW R. MCKINNEY B.A., University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 2000 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Matthew R. McKinney All Rights Reserved HOW DO I LOOK: IDENTITY AND PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE WORK OF NIKKI S. -

Performing Remains

Performing Remains At last, the past has arrived! Performing Remains is Rebecca Schneider's authoritative statement on a major topic of interest to the field of theatre and performance studies. It extends and consolidates her pioneering contributions to the field through its interdisciplinary method, vivid writing, and stimulating polemic. Performing Remains has been eagerly awaited, and will be appreciated now and in the future for its rigorous investigations into the aesthetic and political potential of reenactments. Tavia Nyong’o, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. I have often wondered where the big, important, paradigm-changing book about re-enactment is: Schneider’ s book seems to me to be that book. Her work is challenging, thoughtful and innovative and will set the agenda for study in a number of areas for the next decade. Jerome de Groot, University of Manchester. Performing Remains is a dazzling new study exploring the role of the fake, the false, and the faux in contemporary performance. Rebecca Schneider argues passionately that performance can be engaged as what remains, rather than what disappears. Across seven essays, Schneider presents a forensic and unique examination of both contemporary and historical performance, drawing on a variety of elucidating sources including the “America” plays of Linda Mussmann and Suzan-Lori Parks, performances of Marina Abramovic´ and Allison Smith, and the continued popular appeal of Civil War reenactments. Performing Remains questions the importance of representation throughout history and today, while boldly reassessing the ritual value of failure to recapture the past and recreate the “original.” Rebecca Schneider is Chair of the Department of the Theatre Arts and Performance Studies at Brown University. -

Yasumasa Morimura: in the Room of Art History September 14 – December 22, 2018 Opening Reception: Friday, September 14, 6-8Pm

Yasumasa Morimura: In the Room of Art History September 14 – December 22, 2018 Opening reception: Friday, September 14, 6-8pm Luhring Augustine Bushwick is pleased to present Yasumasa Morimura: In the Room of Art History, the artist’s eighth solo show with the gallery. At the center of Morimura’s photographs is the artist himself in full disguise. For decades Morimura has challenged the conventions of self-portraiture by assuming the likeness of others, demonstrating the plasticity of identity. His approach to image-making stems from a desire to step into and inhabit pictorial space. Using props, makeup, costumes, and digital manipulation, Morimura embodies the personas of prominent figures in history, art, and entertainment as they are represented in popular visual culture. Finding inspiration predominantly within Western iconography, Morimura recasts his subjects and considers his own internalization of the imagery, a reflection of the influx of Western culture in the postwar era in his native Japan. Though his images are not exact duplicates, they bear an uncanny resemblance to their respective sources, operating in a space in which fiction blends with reality, and thereby disrupting the audience’s preexisting associations of the depicted subjects. In the Room of Art History presents examples from two bodies of Morimura’s work: Self-Portraits through Art History (2016), in which the artist has derived his imagery from iconic masterpieces by Caravaggio, Vermeer, Magritte, and van Gogh; and his seminal One Hundred M’s self-portraits (1993-2000), where he emulates celebrities such as Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe, and Brigitte Bardot. In these works, Morimura presents intimate encounters with the artists and actors by reimagining their environments. -

RCA 2014 Body

The Body •Read blurb from syllabus •Focus for today: Contexts for understanding works of art (Artist/viewer) Zhang Huan? Fen Ma Liuming? Zhang Zeduan, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, 11th century Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1889 Mona Hatoum, Van Gogh’s Back, 1995 Photograph “I wanted it to appeal to your senses first maybe or to somehow affect you in a bodily way and then the sort of connotations and concepts that are behind that work can come out of that original physical experience. This is what I was aiming at in the work. I wanted it to be experienced through the body. In other words I want work to be both experienced sensually and intellectually rather than just one dimensionally if you like.” - Mona Hatoum “I don’t think art is the best place to be didactic; I don’t think the language of visual art is the most suitable for presenting clear arguments, let alone for trying to convince, convert or teach.” - Mona Hatoum Yasumasa Morimura, Olympia, 1999 Photograph Edouard Manet, Olympia, 1963 Painting (oil on canvas) “Throughout history artists have drawn, sculpted and painted the human form. Recent art history, however, reveals a significant shift in artists’ perceptions of the body, which has been used not simply as the ‘content’ of the work, but also as canvas, brush, frame and platform. Over the course of the last hundred years artists and others have interrogated the way in which the body has been depicted and how it has been conceived. The idea of the physical and mental self as a stable and finite form has gradually eroded, echoing influential twentieth-century developments in the fields of psychoanalysis, philosophy, anthropology, medicine and science. -

El Requiem De Morimura Yasumasa

DOI 10.3994/RIEAO 2010.01.011 Revista Iberoamericana de Estudios de Asia Oriental (2011) 4: EL REQUIEM DE MORIMURA YASUMASA * Julio César Abad Vidal Resumen: Morimura Yasumasa ᶁ⌠᰼ (Osaka, 1951) es un fotógrafo y performer japonés que ha venido desarrollando desde 1985 una de las más destacadas trayectorias internacionales consagradas a la práctica del apropiacionismo. La labor de Morimura se centra, en ese sentido, en la recreación de obras célebres de la pintura occidental, y japonesa en menor medida, en todos los casos asumiendo la integridad de los papeles que aparecen en escena, lo que le exige una extraordinaria planificación y caracterización. Morimura ha posado, asimismo, para imitar a actrices occidentales, con particular pertinacia, a Marilyn Monroe. Los últimos años, empero, Morimura ha tomado como base para su trabajo no tanto obras de arte cuanto imágenes históricas, a través de la recreación de instantáneas que han obtenido un status icónico en un mundo como el nuestro, saturado de imágenes hasta la extenuación. El * Julio César Abad Vidal es doctor en Estética y Teoría de las Artes y miembro del Grupo de Investigación Asia. Ha dedicado su tesis doctoral a la teoría y la práctica del apropiacionismo. 102 JULIO CÉSAR ABAD presente ensayo se dedicará a la exploración de este mecanismo en la reciente obra de carácter histórico de Morimura Yasumasa. Abstract: Morimura Yasumasa ᶁ⌠᰼ (Osaka, 1951) is a Japanese photographer and performer who has been developing since 1985 one of the most outstanding international careers devoted to the practice of the appropriation. Morimura’s work focuses on both the recreation of famous works by Western painters; and to a lesser extent by Japanese artists. -

Monster Marks March 25 - July 28 2018 Art Museum of the University of Memphis

MONSTER MARKS MARCH 25 - JULY 28 2018 ART MUSEUM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MEMPHIS MONSTER MARKS SHERRY. C.M. LINDQUIST Dorothy Kayser Hohenberg Chair of Excellence in Art History University of Memphis, 2017-19 LENDERS: Michael Allen, Art Museum of the University of Memphis, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Roger Cleaves, Elizabeth Edwards, Le Marquee La Flora, Sherry C.M. Lindquist, Richard Lou, Greely Myatt, Rhodes College, James Patterson, Rushton Patterson Jr., Elliot and Kimberly Perry, Nancy White WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: AMUM staff, Michael Allen, Linde Brocato, Christian Clement, Roger Cleaves, Lorelei Corcoran, Julie Darling, Elizabeth Edwards, Ali Fatemi, Kate Gerry, Austin Griffn, Anne Hogan, John Hochstein, Jed Jackson, Earnestine Jenkins, Vivien Johnson, Le Marquee La Flora, Richard Lou, David Lusk, Marilyn Masler, Asa Mittman, Greely Myatt, Mason Nolen, James Patterson, Rushton Patterson Jr., Elliot and Kimberly Perry, Shannon Perry, Patricia Podzorski, Samira Rahbe, Joshua Roberts, William Short, Virginia Solomon, Teong Tan, Tracy Treadwell, Ky Wagner, Nancy White, Hayley Wood, Kevin Ydrovo GUIDE DESIGN: A.J. Pappas Jason Miller Samira Rhabe REPRODUCTION PHOTOGRAPHY: Jason Miller Art on cover by Myatt Greely Cat. 1. There is something at work in my soul which I do not understand. Robert Walton in Frankenstein, by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley CONTENTS 6 | INTRODUCTION 28 | MONSTERS IN ART HISTORY 29 | SUPERNATURAL BEINGS 43 | MONSTERS AND RULERS 64 | SATIRE AND SOCIAL CRITICISM 72 | MONSTERS IN CONTEMPORARY ART 73 | RACE & RACISM 99 | THE MONSTROUS FEMININE & POSTHUMANISM 111 | B I B L I O G R A P H Y INTRODUCTION This exhibition at the Art Museum of the University of Memphis (AMUM) takes its title from Monster Marks, by Memphis artist Greely Myatt (cat.