SESSION: Dangerous Worlds: Encounters of Art and Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for a New Day Artist Bio

Music for a New Day Artist bio Fariba Davody: Fariba Davody is a musician, vocalist, and teacher who first captured public eye performing classical Persian songs in Iran, and donating her proceeds from her show. She performed a lot of concerts and festivals such as the concert in Agha khan museum in 2016 in Toronto , concerts with Kiya Tabassian in Halifax and Montreal, and Tirgan festival in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2021 in Toronto. Fariba opened a Canadian branch of Avaye Mehr music and art school where she continues to teach. Raphael Weinroth-Browne: Canadian cellist and composer Raphael Weinroth- Browne has forged a uniQue career and international reputation as a result of his musical creativity and versatility. Not confined to a single genre or project, his musical activities encompass a multitude of styles and combine influences from contemporary classical, Middle Eastern, and progressive metal music. His groundbreaking duo, The Visit, has played major festivals such as Wave Gotik Treffen (Germany), 21C (Canada), and the Cello Biennale Amsterdam (Netherlands). As one half of East-meets-West ensemble Kamancello, he composed “Convergence Suite,” a double concerto which the duo performed with the Windsor Symphony Orchestra to a sold out audience. Raphael's cello is featured prominently on the latest two albums from Norwegian progressive metal band Leprous; he has played over 150 shows with them in Europe, North America, and the Middle East. Raphael has played on over 100 studio albums including the Juno Award-winning Woods 5: Grey Skies & Electric Light (Woods of Ypres) and Juno-nominated UpfRONt (Ron Davis’ SymphRONica) - both of which feature his own compositions/arrangements - as well as the Juno-nominated Ayre Live (Miriam Khalil & Against The Grain Ensemble). -

Social Media and Egypt's Arab Spring

Social Media and Egypt’s Arab Spring Lieutenant-Commander G.W. Bunghardt JCSP 40 PCEMI 40 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2014. ministre de la Défense nationale, 2014. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 40 / PCEMI 40 Social Media and Egypt’s Arab Spring By LCdr G.W. Bunghardt This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of stagiaire du Collège des Forces canadiennes one of the requirements of the Course of pour satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. Studies. The paper is a scholastic document, L'étude est un document qui se rapporte au and thus contains facts and opinions, which the cours et contient donc des faits et des opinions author alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not necessarily convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas reflect the policy or the opinion of any agency, nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion d'un including the Government of Canada and the organisme quelconque, y compris le Canadian Department of National Defence. -

Who Has a Voice in Egypt?

#Sisi_vs_Youth: Who Has a Voice in Egypt? ALBRECHT HOFHEINZ (University of Oslo) Abstract This article presents voices from Egypt reflecting on the question of who has the right to have a voice in the country in the first half of 2016. In the spirit of the research project “In 2016,” it aims to offer a snapshot of how it “felt to live” in Egypt in 2016 as a member of the young generation (al-shabāb) who actively use social media and who position themselves critically towards the state’s official discourse. While the state propagated a strategy focusing on educating and guiding young people towards becoming productive members of a nation united under one leader, popular youth voices on the internet used music and satire to claim their right to resist a retrograde patrimonial system that threatens every opposing voice with extinc- tion. On both sides, a strongly antagonistic ‘you vs. us’ rhetoric is evident. 2016: “The Year of Egyptian Youth” (Sisi style) January 9, 2016 was celebrated in Egypt as Youth Day—a tradition with only a brief histo- ry. The first Egyptian Youth Day had been marked on February 9, 2009; the date being chosen by participants in the Second Egyptian Youth Conference in commemoration of the martyrs of the famous 1946 student demonstrations that eventually led to the resignation of then Prime Minister Nuqrāshī. Observed in 2009 and 2010 with only low-key events, the carnivalesque “18 days” of revolutionary unrest in January-February 2011 interrupted what Rather than a conventional academic paper, this article aims to be a miniature snapshot of how it ‘felt’ to live in Egypt by mid-2016 as a member of the young generation (al-shabāb) who have access to so- cial media (ca. -

Vanderbilt University

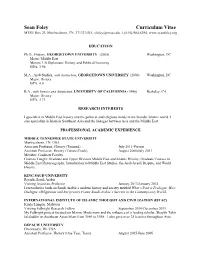

Sean Foley Curriculum Vitae MTSU Box 23, Murfreesboro, TN, 37132 USA, [email protected], 1-(615)-904-8294, www.seanfoley.org EDUCATION Ph.D., History, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY (2005) Washington, DC Major: Middle East Minors: US Diplomatic History and Political Economy GPA: 3.96 M.A., Arab Studies, with distinction, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY (2000) Washington, DC Major: History GPA: 4.0 B.A., with honors and distinction, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA (1996) Berkeley, CA Major: History GPA: 3.73 RESEARCH INTERESTS I specialize in Middle East history and the political and religious trends in the broader Islamic world. I also specialize in Islam in Southeast Asia and the linkages between Asia and the Middle East. PROFESSIONAL ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY Murfreesboro, TN USA Associate Professor, History (Tenured) July 2011-Present Assistant Professor, History (Tenure-Track) August 2006-July 2011 Member, Graduate Faculty Courses Taught: Graduate and Upper Division Middle East and Islamic History, Graduate Courses in Middle East Historiography, Introduction to Middle East Studies, the Arab-Israeli Dispute, and World History. KING SAUD UNIVERSITY Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Visiting Associate Professor January 2013-January 2014 I researched a book on Saudi Arabia’s modern history and society entitled What’s Past is Prologue: How Dialogue, Obligations and Reciprocity Frame Saudi Arabia’s Success in the Contemporary World. INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ISLAMIC THOUGHT AND CIVILIZATION (ISTAC) Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Visiting Fulbright Research Fellow September 2010-December 2011 My Fulbright project focused on Islamic Modernism and the influence of a leading scholar, Shaykh Tahir Jalaluddin on Southeast Asian Islam from 1869 to 1958. I also gave over 25 lectures throughout Asia. -

A Sociolinguistic Study of Code Choice Among Saudis on Twitter

A Sociolinguistic Study of Code Choice among Saudis on Twitter by Saeed Ali Al Alaslaa A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Near Eastern Studies) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mohammad T. Alhawary, Chair Associate Professor Abdulkafi Albirini, Utah State University Professor Marlyse N. Baptista Professor Emeritus Raji M. Rammuny Saeed A. Al Alaslaa [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-0527-2334 © Saeed A. Al Alaslaa 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENT First and foremost, all praise is to the Almighty God for His grace and blessings throughout my entire life. Second, I would like to express my sincere gratitude and deep appreciation to my dissertation committee members for their constructive feedback and the time they dedicated to reading and offering suggestions on the writing of my dissertation. In addition, I want to convey my endless thanks to my advisor, Professor Mohammad Alhawary, who has expanded my knowledge of Arabic linguistics on both levels, theoretical and applied. The Arabic theoretical linguistics classes that I have taken with him were immensely beneficial, including Arabic syntax, semantics, phonology, morphology, historical linguistics, and dialectology. From the applied linguistics perspective, I really benefited from the courses he taught me, such as Arabic second language acquisition, Arabic teaching methodology, as well as the independent classes through which my research topic and interests have evolved and thrived. I am indebted to him for his outstanding direction, guidance, support, patience, and generosity with his time and advice. I hold in the highest esteem everything he has done for me. -

THIS ISSUE THIS ● Sector to Yemen'sfuture ● Ocean Acidification Khettara: a Traditionalyetviable Irrigationoption

Volume 13 - Number 2 February – March 2017 £4 THIS ISSUE: Environment ● West Asia and the Global Environment Outlook ● Ocean acidification● The political ecology of virtual water in Palestine ● The main challenge to Yemen's future ● The challenges of integrating off-grid electricity in Oman's domestic sector ● Sustainable energy planning in MENA ● The evolution of the Nile regulatory regime ● Khettara: a traditional yet viable irrigation option ● PLUS Events in London Volume 13 - Number 2 February – March 2017 £4 THIS ISSUE: Environment ● West Asia and the Global Environment Outlook ● Ocean acidification● The political ecology of virtual water in Palestine ● The main challenge to Yemen's future ● Can Oman’s domestic electricity go off-grid? ● Sustainable energy planning in MENA ● The evolution of the Nile regulatory regime ● Khettara : a traditional yet viable irrigation option ● PLUS Events in London Ibrahim El Dessouki, m3, salteries, 2006. Courtesy of About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Bibliotheca Alexandrina The London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle Volume 13 – Number 2 East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defined and helps to create links between individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. February – March 2017 With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, the LMEI is further strengthened by its academic membership – the largest concentration of Middle East expertise in any institution in Europe. The LMEI also has access to the SOAS Library, which houses over 150,000 volumes dealing with all aspects of the Middle Editorial Board East. -

Amendment to Registration Statement Washington, Dc 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 08/14/2020 3:38:35 PM OMB No. 1124-0003; Expires July 31, 2023 U.S. Department of Justice Amendment to Registration Statement Washington, dc 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended INSTRUCTIONS. File this amendment form for any changes to a registration. Compliance is accomplished by filing an electronic amendment to registration statement and uploading any supporting documents at https://www.fara.gov. Privacy Act Statement. The filing of this document is required for the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, 22 U.S.C. § 611 et seq., for the purposes of registration under the Act and public disclosure. Provision of the information requested is mandatory, and failure to provide the information is subject to the penalty and enforcement provisions established in Section 8 of the Act. Every registration statement, short form registration statement, supplemental statement, exhibit, amendment, copy of informational materials or other document or information filed with the Attorney General under this Act is a public record open to public examination, inspection and copying during the posted business hours of the FARA Unit in Washington, DC. Statements are also available online at the FARA Unit’s webpage: https://www.fara.gov. One copy of eveiy such document, other than informational materials, is automatically provided to the Secretary of State pursuant to Section 6(b) of the Act, and copies of any and all documents are routinely made available to other agencies, departments and Congress pursuant to Section 6(c) of the Act. The Attorney General also transmits a semi-annual report to Congress on the administration of the Act which lists the names of all agents registered under the Act and the foreign principals they represent. -

Uses and Gratification of Spiritual and Religious Music in Egypt: a Descriptive Analysis

Arab Media & Society (Issue 26, Summer/Fall 2018) Uses and Gratification of Spiritual and Religious Music in Egypt: A Descriptive Analysis Hend El Taher Abstract Media is one important constituent of the culture in a society. Its importance is reflected in the contents it presents especially in religion and music. The way both religion and music are blended and used as a medium to gratify certain needs is the interest of this study. In this context, the relationship between religions and music is examined, how music was perceived historically by religious figures, what disputes the music provoked, and how spiritual music is used as an intrapersonal, interpersonal, or a mass communication tool to influence the audience cognitively, behaviorally, and attitudinally. Accordingly, a descriptive survey was conducted on a purposive sample in six academic institutions in Egypt: the American University in Cairo, the British University in Egypt, the German University in Cairo, Cairo University, Ain Shams University, and Al-Azhar University. The Uses and Gratifications and Social Identity theories helped to interpret the data that were collected from 383 respondents. Based on the results, 66.8% of 337 participants use spiritual and religious music for the purposes of emotional therapy. However, using the medium as emotional therapy did not encourage cultural activities such as attending concerts, buying or selling related products, or reading books. "Whenever the soul of the music and singing reaches the heart, then there stirs in the heart that which it preponderates” Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali (Al-Ghazali, 2005; MacDonald, 2009) Introduction Because of its universal language, music has been an important medium throughout the ages. -

Download Hamza Namira Full Album Download Hamza Namira Full Album

download hamza namira full album Download hamza namira full album. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66a3fea76b05c3fc • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. .Insan album mp3 إﻧﺴﺎن - Hamza Namira Insan Released: 2011 Category: Country, Folk Album rating: 4.1 Votes: 912 Size MP3: 1765 mb Size إﻧﺴﺎن :Performer: Hamza Namira Title FLAC: 1894 mb Size WMA: 1486 mb Other formats: XM AUD MMF TTA FLAC AA VOC. Tracklist Hide Credits. Companies, etc. Recorded At – Maestro Studio Recorded At – dB اﺳﺘﻮدﯾﻮ اﻟﺘﻜﺎﻣﻞ – Mastered At – The Cutting Room Recorded At – Leila Studios Recorded At Music Recorded At – Studio Emrec Recorded At – Erekli Tunç Studio Recorded At – Göksun Çavdar Studios Distributed By – Marathon Arabia Manufactured By – Crystalline. Credits. Accordion – Wael El-Naggar* Acoustic Guitar – Gültekin Kaçar, Uğur Varol Acoustic Guitar, Electric Guitar – Erdem Sökmen, Gökay Semercioğlu Backing Vocals – Ahmed Yassin*, Adham Ezzat*, Amir Hossam El-Din*, -

I V the Weight of Hope: Independent Music Production And

The Weight of Hope: Independent Music Production and Authoritarianism in Egypt by Yakein Abdelmagid Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Rebecca L. Stein, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne Allison ___________________________ Charles D. Piot ___________________________ Louise Meintjes ___________________________ miriam cooke Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 i v ABSTRACT The Weight of Hope: Independent Music Production and Authoritarianism in Egypt by Yakein Abdelmagid Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Rebecca L. Stein, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne Allison ___________________________ Charles D. Piot ___________________________ Louise Meintjes ___________________________ miriam cooke An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Yakein Abdelmagid 2018 Abstract This dissertation is an ethnographic study of the independent music scene in Cairo, in which music producers and cultural entrepreneurs who came of age during the 2011 revolution and 2013 counterrevolution hope to constitute alternative music cultures and markets -

LUIS E NSI SILICON VALLEY RIDES BRANDS & BICULTURALISM STREET CRED to the TOP Or the CHARTS

APRIL 30, 2011 www.billboard.com www.billboard.biz THE LATIfIgUE. TOO LEGIT MC HAMMER'S LUIS E NSI SILICON VALLEY RIDES BRANDS & BICULTURALISM STREET CRED TO THE TOP or THE CHARTS. A NATION Of U.S.-BORN SPANISH /POP LIFE SPEAKERS SINGS ALONG k E SPRINGS PLUS I DATES ON HOW WRIGLEY, LOS ANGELES DR PEPPER, AT&T AND OTHERS LEARNED TO THE GENRE - FOO FIGHT FINALLY GET A Na I ALBUM 24-PAGE ak PROGRAM GUIDE TO THE 2011 a LATIN MUSIC CONFERENCE THE MAYOR or NASHVILLE, SOULJA ' S AGAIN, NARM GO FLEET FOXES REVIEWED, LAURA STORY BRE KS OUT AT CHRISTIAN, A HE NUMBER ONE ALBUM IN THE WORLD! I L. WASTING LIGHT "ROCK IS NOT DEAD" - US WEEKLY i CAREER DEFINING "...(WASTING) LIGHT IS A RETURN MUSCULAR ROCK AND ROLL THROWDOWN...A -" _Q - ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY "UNDIMINISHED INTENSITY.. "F00 FIGHTERS BLAZE LIKE * * * *° NEVER BEFORE - PEOPLE * * * - ROLLING STONE SVI ALBUM U.S. U.K. GERMANY CANADA AUSTRALIA SWEDEN NEW ZEALAND FINLAND NORWAY AUSTRIA SWITZERLAND SINGAPORE PRODUCED BY BUTCH VIG MIXED BY ALAN MOULDER °` fooFighters.com facebook.com /foofighters twitter.com /foofighters rcarecords.com poß0 02011 RCA Records, a unit of Sony Music Entertainment. Billboard 1 () I ON THE CHARTS -A IS ALBUMS PAGE ARTIST / TITLE THE BILLBOARD 38 F00 FIGHTERS / 200 WASTING LIGHT HEATSEEKERS ELBOW / 41 BUILD A ROCKET BOYSI TOP 45 ALISON KRAUSS + UNION STATION / COUNTRY PAPER AIRPLANE 45 ALISON KRAUSS + UNION STATION / BLUEGRASS PAPER AIRPLANE WIZ KHAUFA/ TOP R &B /HIP-HOP 46 ROLLING PAPERS CASTING CROWNS / CHRISTIAN 48 UNTIL THE WHOLE WORLD HEARS GOSPEL 48 KIRK FRANKLIN! -

Arab CELEBRITY 100 Rank Name Profession Country Total Social Media

ARAB CELEBRITY 100 RANK NAME PROFESSION COUNTRY TOTAL SOCIAL MEDIA 1 AMR DIAB Singer Egypt 30.26 Million 2 NANCY AJRAM Singer Lebanon 48.14 Million 3 ELISSA Singer Lebanon 43.48 Million 4 KADIM ALSAHER Singer Iraq 19.69 Million 5 NAJWA KARAM Singer Lebanon 26.58 Million 6 ADEL EMAM Actor Egypt 16.44 Million 7 ASSALA NASRI Singer Syria 22.61 Million 8 AHLAM ALSHAMSI Singer UAE 21.5 Million 9 RAGHEB ALAMA Singer Lebanon 13.05 Million 10 GEORGE WASSOUF Singer Syria 9.61 Million 11 AHMED HELMY Actor Egypt 19.55 Million 12 TAMER HOSNY Singer Egypt 29.8 Million 13 SHERINE ABDEL-WAHAB Singer Egypt 22.52 Million 14 MOHAMED HAMAKY Singer Egypt 19.8 Million 15 CYRINE ABDELNOUR Singer Lebanon 16.24 Million 16 WAEL JASSAR Singer Lebanon 15.45 Million 17 AHMED EL SAKKA Actor Egypt 14.96 Million 18 HUSSAIN AL JASSMI Singer UAE 14.31 Million 19 FAIRUZ Singer Lebanon 8.37 Million 20 SABER ALREBAI Singer Tunisia 7.89 Million 21 AMAL MAHER Singer Egypt 13.13 Million 22 MYRIAM FARES Singer Lebanon 23.14 Million 23 SAMIRA SAID Singer Morocco 8.3 Million 24 CAROLE SAMAHA Singer Lebanon 13.68 Million 25 HASSAN EL SHAFEI Composer Egypt 13.04 Million 26 MOHAMED MOUNIR Singer Egypt 8.09 Million 27 HEND SABRY Actor Tunisia 8.73 Million 28 DONIA SAMIR GHANEM Actor Egypt 10.32 Million 29 MOHAMMED ASSAF Singer Palestine 15.83 Million 30 MOHAMED SOBHI Actor Egypt 7.15 Million 31 NAWAL AL ZOGHBI Singer Lebanon 12.98 Million 32 YARA Singer Lebanon 16.39 Million 33 HAIFA WEHBE Singer Lebanon 21.96 Million 34 MAHER ZAIN Singer Lebanon 31.8 Million 35 RAMEZ GALAL Actor/Presenter