Bonus Marchers & False Economies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wininger Family History

WININGER FAMILY HISTORY Descendants of David Wininger (born 1768) and Martha (Potter) Wininger of Scott County, Virginia BY ROBERT CASEY AND HAROLD CASEY 2003 WININGER FAMILY HISTORY Second Edition Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 87-71662 International Standard Book Number: 0-9619051-0-7 First Edition (Shelton, Pace and Wininger Families): Copyright - 2003 by Robert Brooks Casey. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be duplicated or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the authors. This book may be reproduced in single quantities for research purposes, however, no part of this book may be included in a published book or in a published periodical without written permission of the authors. Published in the United States by: Genealogical Information Systems, Inc. 4705 Eby Lane, Austin, TX 78731 Additional copies can be ordered from: Robert B. Casey 4705 Eby Lane Austin, TX 78731 WININGER FAMILY HISTORY 6-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................6-1-6-8 Early Wininger Families ............6-9-6-10 Andrew Wininger (31) ............6-10 - 6-11 David Wininger (32) .............6-11 - 6-20 Catherine (Wininger) Haynes (32.1) ..........6-21 James S. Haynes (32.1.1) ............6-21 - 6-24 David W. Haynes (32.1.2) ...........6-24 - 6-32 Lucinda (Haynes) Wininger (32.1.3).........6-32 - 6-39 John Haynes (32.1.4) .............6-39 - 6-42 Elizabeth (Haynes) Davidson (32.1.5) ........6-42 - 6-52 Samuel W. Haynes (32.1.7) ...........6-52 - 6-53 Mary (Haynes) Smith (32.1.8) ..........6-53 - 6-56 Elijah Jasper Wininger (32.2) ...........6-57 Samuel G. -

The Natio Egionnaire Dedicated to the the Firing Line

I The Natio egionnaire Dedicated to the the Firing Line entered M »eeoml clau mallei 1>J0 J 3 Indianapolis, Indiana, August a, 1946 at postolllce, liniianatxiiia, Iri.ii.i::.' ' I Vol. 12 <J I TERMINAL LEAVE PAY BILL AND PENSION INCREASE ARE PASSED 100 Boys in Washington, D. G, Legion Radio Voice Measures to White House Is Never Silenced For President's Signature For Forum on Government There's a 15-Minute Pro- Legislative Review Shows Insurance Bill Signed; Boys Slates' Top Officers and High School Leaders Are gram for Every Quarter Universal Military Training Stymied, Guests of American Legion for Practical Course Hour in 1946 Other Bills Hanging Fire of Study at National Capital American Legion radio activities ■WASHINGTON, D. C—A strong tension gripped Capitol averaging more than one complete One hundred young men are gathered in Washington, D. C., Hill as American Legion legislative representatives thrust a foot 15-minute program for every quar- into closing Congressional doors and staged a spectacular last as we go to press, as guests of the national organization of'Ine ter hour of 1946 are included in minute rally to ram through the Terminal Leave and Pension American Legion, for a five-day Boys' Forum of National Cov- the schedules of the Radio Branch, Increase bills, as a brilliant climax to the Legion's most success- The American Legion's National crnment. , ful legislative year. These young men come from practically every domest.c de- Public Relations Division. The Terminal Leave bill was passed on July 31 and was sent Latest surveys show that Indi- partment of The American Legion-two from each state. -

Law Alumni Journal

et al.: Law Alumni Journal A PUBLICATION OF THE LAW ALUMNI SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Fall 1965 Volume!, Number 1 Published by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, 2014 1 Penn Law Journal, Vol. 1, Iss. 1 [2014], Art. 1 'law Alwnni Journal - Editor: VOLUME I NUMBER 1 FALL 1965 Barbara Kron Zimmerman, '56 Associate Editor: James D. Evans, Jr. TABLE OF CONTENT S Alumni Advisory Committee: Robert V. Massey, '31 ABORTING STATE COURT TRIAL IN CRIMINAL J. Barton Harrison, '56 CIVIL RIGHTS PROSECTIONS by Professor Anthony G. Amsterdam, '60 The Law Alumni Journal is published three times a year by the Law Alumni CHURCH AND STATE CONFERENCE HELD AT Society of the University of Pennsylvania LAW SCHOOL 2 for the information of its members. BICENTENNIAL FELLOWS 3 Please address all communications and manuscripts to: THE EVIL PRACTICE OF MAJORITY OPINIONS 4 The Editor A Report by Arnold Cohen, '63, on Professor Law Alumni Journal University of Pennsylvania Haskins' Address to the Coif Chapter Law School CLASS OF 1968 SERVICE MINDED 4 Thirty-fourth and Chestnut Streets Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 LAw H JvLn.LLrVH LA~. vALG1viNG-FINAL REPOR r 1964 1765 5 Benjamin Franklin Associates 6 Century Club 6 Report of Classes 8 Contributors 10 Regarding Law School Annual Giving 13 Cover: Professor Noyes E. Leech, '48, A Glance at Ten Years of Annual Giving 14 teaching Creditor's Rights class in McKean Hall. Corporate Matching Gift Program 14 Summary of Regions 18 Law Alumni Day 19 KICKOFF LUNCHEON FOR 1965-66 ALUMNI ANNUAL GIVING 20 SPECIAL Al\INOUNCEMENT: PICTURE CREDITS GOWEN FELLOWSHIPS AVAILABLE 20 cover Peter Dechert pages 2, 3, 9, COMMENTS ON LAW IN THE AFRICAN 18,19,22 Frank Ross COUNTRIES 21 page 20 Walter Holt page 23 Cherry Hill Portrait Studio ALUMNI NOTES 22 page 24 Jules Schick Studio PROFESSOR A. -

Feature Article

3 ABOUT WISCONSIN 282 | Wisconsin Blue Book 2019–2020 Menomonie residents celebrated local members of the Wisconsin National Guard who served during the Great War. As Wisconsin soldiers demobilized, policymakers reevaluated the meaning of wartime service—and fiercely debated how the state should recognize veterans’ sacrifices. WHS IMAGE ID 103418 A Hero’s Welcome How the 1919 Wisconsin Legislature overcame divisions to enact innovative veterans legislation following World War I. BY JILLIAN SLAIGHT he Great War seemed strangely distant to Ira Lee Peterson, even as his unit camped mere miles from the front lines in France. Between drills and marches, the twenty-two-year-old Wisconsinite swam in streams, wrote letters home, and slept underneath the stars in apple orchards. TEven in the trenches, the morning of Sunday, June 16, 1918, was “so quiet . that all one could hear was the rats running around bumping into cans and wire.” Peterson sat reading a book until a “whizzing sound” cut through the silence, announcing a bombardment that sent him and his comrades scurrying “quick as gophers” into their dugout.1 After this “baptism with shell fire,” Peterson suffered a succession of horrors: mustard gas inhalation, shrapnel wounds, and a German 283 | Wisconsin Blue Book 2019–2020 COURTESY LINDA PALMER PALMER LINDA COURTESY WILLIAM WESSA, LANGLADE COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY HISTORICAL COUNTY LANGLADE WESSA, WILLIAM Before 1914, faith in scientific progress led people to believe that twentieth-century war would be less brutal. In reality, new technologies resulted in unprecedented death and disability. (left) American soldiers suffered the effects of chemical warfare despite training in the use of gas masks. -

And National Trades' Journal

VER ITABLE CHARTISIS. Q THE wrcs pontttiw. Very much ,obli ged to «v J ioeSBB,—I am " " '¦'¦"- ~" so laces. THE "T IMES. " who have invited me to man y p Sheffield at half-past two on ?tall be at TO THE EDITOR OP TllJJ NOjfTHEK.v star . attend the to Wednes day next, to soiree Sir , — Our " public inst ructor " are unquestion- ably a i vn I have been invited , and I shall be at most sage and consistent race of men. They stem perfect Friday nest. I will attend all the adepts in the art of deception and gul- I Sue on labil ity, Every ar ticle from their slop is i-nffed off from -which I ha re received ther towns soon as genuine , while the eommodiriesof their rivals ar e " , but I cannot yet name the day, as ueclar. d to be spurious and compounded of the 1not ati ons , is required in London now that most injuri ous ingredients *. Of courxe , each vend v pres ence the best and Company is being wound-u p—but I most efficaciou s remed y for perfecting 2a Land AND the cur e of a ' TRADES' nat ion in NATIONAL s ills, dilapidated , JOURNAL and restoring ^„„ nd trust God that I shall soon be nope «"» . _ » <-,!, - _ constitut ions to their pristine ?igour. Some o£ irit of Chartism.- once more. th ose hie to rouse the sp % philanth ropic gentr y declare tha t John Bull is 8 TOL , U86I. tull ot wounds atte nd ed the dinner given to K.OSSUTH on ¦ " BV P. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Jr

1946 .CONGRESSIONAL RECO_RP-HOUSE 4.559 Ralph Scheidenhelm Frank R. Thienpont Arthur L. Child 3d Ralph P. Parker Leonard F. Schempp,Edward W. Thomas Andrew s. Dowd Walter T.Pate, Jr. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Jr. John C. Thompson Stuart J. Evans John L: Prehn, Jr: Robert E. Schenk Robert W. Thompson · John E. Fjelsta Robert H. Pylkas TuESDAY, MAY 7, 1946 Stanley J. Schiller William F. Thompson Alton C. Gallup · George D. Riley, J:r, Charles H. Schnorr, Jr.Neil W. Thomson Nathaniel Heller Kenneth McD. Robin- The House met at 12 o'clock noon. John A. Schomaker John L. Thornton Arthur W. Holfield, Jr. son Rev. Bernard Braskamp, D. D., pastor Arnold R . SchuknechtFrank A. Thurtell Ben Johnson 3d Elliot R. Rose of the Gunton-Temple Memorial Presby Foster R. Schuler Thomas J. Tiernan Warren B. Johnson Louis P. Rossi Robert E . Schwartz Curran C. Tiffany terian Church, Washington, D. C., offered John F. Jones Rufus E. Sadler, Jr. the following prayer: Edward A. Scoles Herbert I. Tilles William B. Kash Charles H. Schoman, Robert L. Scott David R. Toll William K. Lampman Jr. 0 Thou gracious benefactor, whose William L. Scurlock Donald L. Toohill George H. L!ming Eugene A. Shaw heart responds to every human need, we Kenneth P . Sears John W. Townes, Jr. Edward B. Langmuir, Waldo D. Sloan, Jr. Chester H. Shaddeau,Earle N. Trickey thank Thee for the many tokens of the Jr.· Ralph McM. Tucker Jr. Richard J . Sowell eternal truth that Thou art man's unfail- Donald P. Shaver John G. Turner Herbert M. -

The Bonus Army - March on Washington

Name: edHelper The Bonus Army - March on Washington November 11, 1918 - Armistice Day. The War to End all Wars was over. Weary veterans came home. They left many slain companions behind and brought home a lifetime of bloody memories. The Great War had been one long horror of death and destruction. In the months that followed, soldiers and their families began the process of redefining their lives after the trauma of war. Many servicemen returned to find that their jobs had been taken by others. Besides that, the economic climate in America had shifted. While the soldiers were away sacrificing years of their lives, wages had gone up. Those who had not gone to war were enjoying much bigger paychecks than the veterans had earned in the same jobs before the war. Soldiers' pay and unemployment seemed a bitter reward for all the veterans had given. Disillusioned veterans began to press the government for compensation. In 1924, Congress approved the Soldiers' Bonus Act. The veterans received certificates that would be redeemable in 1945 for a cash value of about $1,000 each. It seemed a distant consolation, but perhaps it was better than nothing. Then came 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression. The sudden economic crisis jolted everyone, especially the disabled and the widows and children of soldiers killed in Europe. Unemployment was rampant. Many who had given everything for America on the battlefields of the Great War were now trying desperately to keep their families from starving. Naturally, veterans in these dire straits thought of the bonuses promised by the government. -

Texas and the Bonus Expeditionary Army

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 23 Issue 1 Article 7 3-1985 Texas and the Bonus Expeditionary Army Donald W. Whisenhunt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Whisenhunt, Donald W. (1985) "Texas and the Bonus Expeditionary Army," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol23/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 27 TEXAS AND THE BONUS EXPEDITIONARY ARMY by Donald W. Whisenhunt By 1932 the United States was in the midst of the most severe economic depression in its history. For several years, but especially since the Stock Market Crash of 1929, conditions had been getting worse by the month. By the summer of 1932 the situation was so bad that many plans to end the depression were put forward by various groups. Texas suffered from the Great Depression just as much as the rest of the country.' Rising uuemployment, a decline in foreign commerce, and the reduction of farm prices combined to make life a struggle during the 1930s. When plans, no matter how bizarre, were offered as solu tions, many Texans joined the movements. One of the most interesting and one that gathered much support was the veterans bonus issue. -

Thenatio WE HAVE WON THE

«•». Jin.v, 1945 W«/; /or Optometrists ;e Council of the ssociation of Boards n Optometry at its g in Indianapolis, B, 1945, adopted the ltion affecting vet- egionnaire POSTMASTER:TheNatio PLEASE DO NOT SEND NOTICE War II: ^v ON FORM 35TB if a notice has already been sent lere are many re- M J) to the publishers or The American Legion Magazine, Dedicated to the the Firing Line il of World War II Chicago. III., with respect to a copy similarly ented from taking addressed. iminations previous No. 8 ng into the armed Vol. 11 Indianapolis. Ind., August, 1945 t graduation; and lany returning 11- i of World War II /antageous to relo- states; now, there- tiat In view of the lls situation which yond the control of -e recommend that WE HAVE WON THE WAR; give special consid- lests for reciprocity by such honorably ?terans consistent itandards of the op- ston." WHAT ABOUT THE PEACE? . Scrugfiam, ionnaire, Dies f James G. Scrug- la, a past national r and past depart- NATIONAL CONVENTION IN CHICAGO NOV. 18-20; er of The American m June 23 at the in San Diego, Cal., ilment. rved as department ARMED FORCES ELIGIBLE TO JOIN LEGION NOW 1920; as national r during 1920-21; ber of the national Preserve Civilian Economy; Prevent Inflation and High Approval Now of nittee from 1920 to Full Delegate a member of Corn- Prices; Grant Job-Seeking Furloughs to Those Who Military Training Marshal Foch Tour Convention On rved on the national Want Them, Says National Commander Law Asked hy NEC mittee in 1920, 1922 As War Ends the national World SCHE1BERL1NO Prepare Now for the Fall ee in 1925; and was By EDWARD N. -

Historically Speaking the U.S

Historically Speaking The U.S. Army and the Great Depression he news of late has been eerily remi- By Brig. Gen. John S. Brown a government that knows how to deal Tniscent of our slide into the Great U.S. Army retired with a mob.” Depression. Once again, a perfect storm In March 1933, newly elected President combining declining demand, indebtedness, income in- Franklin Delano Roosevelt took a far less confrontational equities, speculative business practices, corporate malfea- approach. Waving aside concerns about deficit spending, sance and hemorrhaging confidence is shaking our eco- he quickly enacted a virtual “alphabet soup” of new federal nomic foundations. Fail-safes such as the FDIC and Social agencies. Most of these were designed to have a direct and Security, and the federal government’s enhanced capabili- immediate impact on working families, and some were ties to react, will undoubtedly mitigate the worst that simply federal job creation programs. The Civil Works Ad- could happen, but most analysts predict we are in for pro- ministration provided jobs to four million Americans, and longed hard times and a difficult recovery. Without overre- the Public Works Administration pumped $3.3 billion (a acting to contemporary circumstances, it might be worth- huge sum at the time) into construction and infrastructure. while to reflect on the ramifications our nation’s greatest Both initiatives drew heavily on the expertise of the Army economic disaster had on our Army. Corps of Engineers. Desperate people do desperate things. During the Great The Civilian Conservation Corps, which ultimately put Depression, waves of layoffs, foreclosures, estate auctions approximately two-and-a-half million young men to work and other bad news precipitated public unrest and often on arduous outdoor projects, involved the Army even more public violence. -

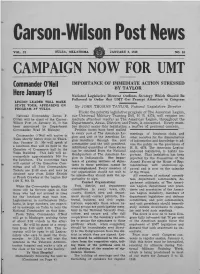

Carson-Wilson Post News

• Carson-Wilson Post News VOL. 12 TULSA, OKLAHOMA • JANUARY 2, 1948 NO. 16 CAMPAIGN NOW FOR UMT IMPORTANCE. OF IMMEDIATE ACTION STRESSED Commander O'Neil BY TAYLOR Here January 15 National Legislative Director Outlines Strategy Which Should Be Followed in Order that UMT Get Prompt Attention in Congress LEGION LEADER WILL MAKE STATE TOUR, APPEARING ON By JOHN THOMAS TAYLOR, National Legislative Director PROGRAM AT TULSA. Under the priority legislative program of The American Legion, National Commander James F. our Universal Military Training Bill, H. R. 4278, will require im O'Neil will be guest of the Carson mediate attention insofar as The American Legion, throughout the Wilson Post on January 15, it has Departments, Areas, Districts and Posts, is concerned. Every mem been announced by Department ber should make this legislation a ma{ter of personal concern. Commander Brad M. Risinger. Petition forms have been mailed to every post of The American Le meetings of luncheon clubs, and Commander O'Neil will arrive in gion and unit of the American Le other societies for the dissemination Tulsa shortly before noon on Thurs gion Auxiliary through the post of information and knowledge to ad day, January 15. He will speak at commander and the unit president. vise the public on the 'provisions of a luncheon that will be held in the Additional quantities of these lorms H. R. 4278, The American Legion Chamber of Commerce hall in the can be obtained from the National endorsed legislation, is highly im Tulsa Building. This hall win ac Headquarters of The American Le portant. -

The Independent Review

Volume 20, Number 1 Spring 2010 Unemployment Then and Now by William F. Shughart II* n March of 1933, when Mobilizing America for global war, outfitting Ithe Great Depression had youngsters of the so-called Greatest Generation driven the U.S. economy to with military uniforms, equipping them with M-1 rock bottom, the unemploy- rifles and sending many ment rate stood at 25 per- to die in France’s hedge- cent: One in four Americans rows or the South Pacific’s who had jobs in 1929 were jungles not only lowered queuing on bread lines rather than the overall unemploy- working on assembly lines. ment rate dramatically, The unemployment rate remained but also drew millions of at historically high levels throughout women into the workforce the following decade. De- to help manufacture the spite massive increases armaments that, in some in federal government cases, would maim or kill their fathers, spending under the husbands, and sons. programs of President Why did unemployment persist af- Roosevelt’s New Deal, ter FDR took the oath of office in March 14 percent of the labor 1933 pledging to end Herbert Hoover’s perceived force still had no jobs indifference to the visible economic hardships vis- in 1941. Unemployment ited on hordes of his fellow citizens, epitomized did not fall into single digits until after Pearl by General Douglas MacArthur’s brutal routing Harbor, when millions of men were drafted into of the “Bonus Army” gathered on the mudflats of the armed forces to fight the first axis of evil. Anacostia? Didn’t the alphabet soup of work relief programs the president subsequently launched— * William F.