Exploring Worldwide Collecting Consumption Behaviors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

WILDLIFE WATCHING and TOURISM a Study on the Benefits and Risks of a Fast Growing Tourism Activity and Its Impacts on Species IMPRINT

WILDLIFE WATCHING AND TOURISM A study on the benefits and risks of a fast growing tourism activity and its impacts on species IMPRINT Published by United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Secretariat of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). Wildlife Watching and Tourism: A study on the benefits and risks of a fast growing tourism activity and its impacts on species UNEP / CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 68 pages. Produced by UNEP / CMS Convention on Migratory Species and TUI Author Richard Tapper, Environment Business & Development Group, E-mail: [email protected] Editing & Coordinator Paola Deda, CMS Secretariat, E-mail: [email protected] Publishing Manager Muriel M. Mannert Design Karina Waedt © 2006 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) / Convention on Migratory Species (CMS). This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permis- sion in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. DISCLAIMER The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP or contributory organizations.The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contri- butory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area in its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

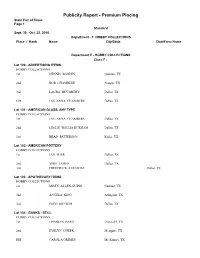

2016 Pub Rpt HOBBY COLLECTIONS Revised

Publicity Report - Premium Placing State Fair of Texas Page 1 Standard Sept. 30 - Oct. 23, 2016 Department - F HOBBY COLLECTIONS Place / Rank Name City/State Club/Farm Name Department F - HOBBY COLLECTIONS Class F - Lot 100 - ADVERTISING ITEMS HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st DENNIS BARDIN Quinlan, TX 2nd BOB CHAMBLEE Prosper, TX 3rd LAURA MCCARTHY Dallas, TX HM LOU ANNA CHAMBERS Dallas, TX Lot 101 - AMERICAN GLASS, ANY TYPE HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st LOU ANNA CHAMBERS Dallas, TX 2nd LESLIE WALLIS DURHAM Dallas, TX 3rd BRAD PATTERSON Keller, TX Lot 102 - AMERICAN POTTERY HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st JAN WIER Dallas, TX 2nd MIKE JAMES Dallas, TX 3rd FREDERICK STANWISE Dallas, TX Lot 103 - APOTHECARY ITEMS HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st MISTY ALLEN-GUINN Garland, TX 2nd ANGELA KING Arlington, TX 3rd PATTI BREWER Dallas, TX Lot 104 - BANKS - STILL HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st CHARLES BERG DALLAS, TX 2nd EVELYN CHEEK Mesquite, TX HM CAROL A GRIMES Mc Kinney, TX Lot 105 - BARBER ITEMS HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st RICK LEAL Grand Prairie, TX 2nd COLLIN PITTMAN Dallas, TX 3rd JANET L BLACKWELL Richardson, TX Lot 106 - BASKETS-CRYSTAL OR GLASS ONLY HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st JUDY SPENCER CREED Euless, TX Lot 107 - BELT BUCKLES HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st ERNEST CARR Duncanville, TX 2nd ANN PERDUE Carrollton, TX 3rd SUE TURNER FERRIS, TX Printed At 09/06/2016 12:59:42 PM Publicity Report - Premium Placing State Fair of Texas Page 2 Standard Sept. 30 - Oct. 23, 2016 Department - F HOBBY COLLECTIONS Place / Rank Name City/State Club/Farm Name Lot 108 - BOOKS, CHILDREN'S HOBBY COLLECTIONS 1st LINDA ROE -

Creative Industries

KEY INDUSTRY CREATIVE INDUSTRIES Colorado is a global leader in the creative INDUSTRY FACTS industries, which include six creative sub-groups: design, film and media, heritage, literary and publishing, performing arts, and visual arts and crafts: • Design applies artistic content to commercial products, services and the $300 environment, and includes companies that purchase fabrics, design, cut, sew and assemble garments and other sewn products ranging from footwear to handbags and luggage. Companies that provide design-related services (such as architectural, MILLION home interiors, graphic, and advertising-related agencies) are also included. EXPORTS 2013 TOTAL • Film and media companies provide technical and distributive elements of EXPORT Colorado’s entertainment industry, including companies that provide technical TOP 3 MARKETS production support systems such as sound, lighting, digital art, animation, sets and studios, broadcasting and distribution channels via motion picture, video and music 1. Canada production companies. • Heritage includes Colorado’s historical sites, museums and botanical gardens. 2. Mexico • Literary and publishing companies print newspapers, books, labels, stationary 3. Japan and other materials, and perform support activities such as data imaging and bookbinding. Companies that wholesale and publish newspapers, magazines, books, directories and mailing lists, and software are also included. • Performing arts includes actors, musicians, promoters, producers and directors and the venues at which they perform. Musical instrument and supply stores are also NUMBER OF included. COMPANIES • Visual arts and crafts companies manufacture metal, wood, jewelry, silverware, dolls and stuffed toys, games, musical instruments, wholesale toy and hobby goods, jewelry and precious metals. Photography studios, galleries, photofinishing laboratories, fine arts schools, art dealers, and sewing and needlework stores are also included. -

MM Redesigned.Indd

� �� � � � � � � � � � � � RESORTS PRSRT STD PRSRT PARKS AND AND PARKS WALT DISNEY DISNEY WALT U.S. POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S. FEB 2005 happiest celebration ON EARTH PO Box 10045 • Lake Buena Vista, FL 32830-0045 Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Walt ©Disney 4050200CMD0302 3 mickey monitor news Happiest Celebration On Earth starts May 5 If you recall any of the elaborate Disney celebrations, you know it takes something really gigantic to outdo every single one of them. But this event is truly the most exciting ever—because it’s the first global celebration. In honor of the 50th anniversary of Disneyland® Park, we’re celebrating half a century of Theme Park and Resort magic with the biggest bash in Disney history. Get ready And you’ll enjoy more Walt Disney World® fun than ever, because new attractions and entertainment are coming as part of the festivities. for the biggest “The shows and attractions Guests love best at Disney Parks worldwide were selected for the celebration,” says Joe Rand, bash of all Walt Disney World Segment Manager. “All this great fun was gathered up and will be brought to the four Walt Disney World Theme Parks in Florida.” In other words, we throw the party, and you get new fun to enjoy as your “gifts.” As a Passholder, you’ll have the inside track on every new attraction and show even before it comes to life. Read on for more details on all the new fun in this special pre- view issue, or visit happiestcelebration.com. Go behind-the-scenes at Happiest Celebration On Earth Hey, check out Talk about your golden opportunities. -

Theme Park Fandom Theme Park Fandom

TRANSMEDIA Williams Theme Fandom Park Rebecca Williams Theme Park Fandom Spatial Transmedia, Materiality and Participatory Cultures FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Theme Park Fandom FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence The book series Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence provides a platform for cutting-edge research in the field of media studies, with a strong focus on the impact of digitization, globalization, and fan culture. The series is dedicated to publishing the highest-quality monographs (and exceptional edited collections) on the developing social, cultural, and economic practices surrounding media convergence and audience participation. The term ‘media convergence’ relates to the complex ways in which the production, distribution, and consumption of contemporary media are affected by digitization, while ‘participatory culture’ refers to the changing relationship between media producers and their audiences. Interdisciplinary by its very definition, the series will provide a publishing platform for international scholars doing new and critical research in relevant fields. While the main focus will be on contemporary media culture, the series is also open to research that focuses on the historical forebears of digital convergence culture, including histories of fandom, cross- and transmedia franchises, reception studies and audience ethnographies, and critical approaches to the culture industry and commodity -

2021 Outdoor Participation Trends Report Table of Contents

2021 OUTDOOR PARTICIPATION TRENDS REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Outdoor Participant Diversity The Next A Detailed Methodology Summary Participation Profile Generation Look Snapshot EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In 2020, 53 percent of Americans ages 6 and over participated in outdoor recreation at least once, the highest participation rate on record. As the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged communities and forced a nationwide shutdown, outdoor spaces became places of refuge to safely socialize, improve physical and mental health, connect with family and recover from screen fatigue. Remarkably, 7.1 million more Americans participated in outdoor recreation in 2020 than in the year prior. Despite these gains, nearly half of the U.S. population did not share in the proven, positive health outcomes of outdoor physical activity. COVID-19 inspired huge TERMINOLOGY participation growth, as detailed throughout this report. These PARTICIPANT A survey respondent who reported one-year gains, however, did Outdoor Foundation’s Thrive Outside participating in at least one outdoor activity not fundamentally alter the initiative is focused on reversing the in calendar year 2020. Participants often report undertaking multiple activities long-term challenges faced declining trend of outdoor engagement. multiple times throughout the year. by the outdoor industry. To build and strengthen networks that provide children and families with The outdoor industry and its PARTICIPATION RATE repeat and reinforcing experiences in partners are positioned to The proportion of a group that participated the outdoors, Thrive Outside awards in outdoor recreation or in an outdoor champion new ways to engage multiyear, capacity-building grants to activity. For example, if 6 in 10 teenagers outdoor participants and invest diverse communities. -

The Creative Economy of Houston

JULY 2012 THECREATIVE ECONOMY OF HOUSTON A comprehensive sTUDY OF creaTIVE-SECTor INDUStrieS and their IMPACT ON THE HOUSTON ECONOMY Commissioned by Houston Arts Alliance and University of Houston in partnership with Greater Houston Partnership Data and Analysis by EMSI Thank you to all of the many thoughtful participants in bringing this study to a reality. Nearly three years WELCOME LETTER ago, Houston Arts Alliance and University of Houston convened a group of creative, academic and policy leaders to discuss the broad creative sector in Houston. A few preliminary take-aways have informed the work since then. Among them is the sense that the delineation between the for-profit creative sectors and the non-profit arts is now highly porous. Artists and other creatives move fluidly between work in major arts institutions, community-based organizations, film, design and other creative endeavors. The “arts” today are about creative expression and creative experience, and don’t fall neatly within for-profit and non-profit parameters. We need to shift the perception from the arts as a quality of life attraction for a well-qualified workforce, to the creative sectors as a tremendously powerful component of the economy unto itself. I believe this study reflects these early ideas. This is a conservative study. By design, we asked our colleagues at EMSI to mirror the study as much as possible to successful studies in other major US cities, but to tailor it to Houston. The result are findings that are defendable, easy to grasp, and are presented within the context of Houston’s job sectors. -

Economic Analysis of Outdoor Recreation in Washington State 2020

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF OUTDOOR RECREATION IN WASHINGTON STATE 2020 UPDATE AUTHORS Johnny Mojica Project Director, Earth Economics Angela Fletcher Project Director (Ecosystem Services), Earth Economics Suggested Citation: Mojica, J., Fletcher, A., 2020. Economic Analysis of Outdoor Recreation in Washington State, 2020 Update. Earth Economics. Tacoma, WA. The authors are responsible for the content of this report. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Research support was provided by Ken Cousins, Trygve Madsen, and Will Golding (Earth Economics) Report design by Cheri Jensen (Earth Economics) Map design by Corrine Armistead (Earth Economics) Project Oversight by Maya Kocian (Earth Economics) Funding provided by: Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office, Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI) We would also like to thank: Wendy Brown (RCO), Kaleen Cottingham (RCO), Jon Snyder (Office of the Governor), Brock Milliern (DNR), Leah Dobey (DNR), Cassie Bordelon (DNR), Tom Bugert (DNR), and Marc Berejka (REI). Earth Economics’ Board of Directors Morgan Collins, David Cosman, Judy I. Massong, Nan McKay, Craig Muska, Ingrid Rasch, and Molly Seaverns. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary 3 2 Introduction 7 Report Overview 7 Background on Washington State 7 3 Concepts and Methods 9 The Outdoor Recreation Economy 10 Consumer Surplus and Environmental Benefits 11 Recreation Expenditure Flow 12 4 Expenditures and Economic Contribution of Outdoor Recreation in Washington State 13 Outdoor Recreation Participation and Spending -

2019 Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry

2019 ESSENTIAL FACTS About the Computer and Video Game Industry Foreword Table of Contents 2018 was a record-breaking year for our industry, with total video game sales exceeding $43.4 billion. Over 164 million adults in the United States play video games, and three-quarters of all Americans have at least one gamer in their Foreword 3 household. It’s now more important than ever to understand who America’s video At-A-Glance 5 game players really are and what’s driving them. Average Gamer 6 That’s why I’m thrilled to share the 2019 Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry. For the first time, we at the Entertainment Software Social & Lifestyle 9 Association have taken a comprehensive look at the individual Americans who enjoy video games and their lifestyles in order to better understand their profiles Parents of Gamers 10 and interests. Households with Children 13 The resulting data speaks for itself. Video game players represent a diverse cross- Who Plays 15 section of the American population spanning every age, gender, and ethnicity. They live healthy lives, are civically engaged, and are socially active. More than Purchasing 20 three-quarters report that video games provide them with mental stimulation (79%) as well as relaxation and stress relief (78%). The role of video games in the ESA Partners 22 American family is also changing: nearly three-quarters (74%) of parents believe video games can be educational for their children, and more than half (57%) enjoy ESA Members 23 playing games with their child at least weekly. -

America's Creative Economy: a Study of Recent Conceptions, Definitions, and Approaches to Measurement Across the USA

America's Creative Economy: A Study of Recent Conceptions, Definitions, and Approaches to Measurement Across the USA Christine Harris Christine Harris Connections Margaret Collins Center for Creative Economy Dennis Cheek National Creativity Network This project was supported in part or in whole by an award from the Research: Art Works program at the National Endowment for the Arts: Grant# 12-3800-7015. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Office of Research & Analysis or the National Endowment for the Arts. The NEA does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information included in this report and is not responsible for any consequence of its use. AMERICA’S CREATIVE ECONOMY A STUDY OF RECENT CONCEPTIONS, DEFINITIONS, AND APPROACHES TO MEASUREMENT ACROSS THE USA A REPORT FROM THE CREATIVE ECONOMY COALITION (CEC) A WORKING GROUP OF THE NATIONAL CREATIVITY NETWORK CHRISTINE HARRIS MARGARET COLLINS DENNIS CHEEK NATIONAL CREATIVITY NETWORK, OKLAHOMA CITY, OK, IN COLLABORATION WITH CREATIVE ALLIANCE MILWAUKEE, AUGUST 2013 AMERICA’S CREATIVE ECONOMY A STUDY OF RECENT CONCEPTIONS, DEFINITIONS, AND APPROACHES TO MEASUREMENT ACROSS THE USA A Report from the Creative Economy Coalition (CEC), a Working Group of the National Creativity Network ! Oklahoma City, OK: National Creativity Network Reproduction Rights: in collaboration with Creative Alliance Milwaukee, Organizations and individuals may freely August 2013 reproduce this report in whole or in part subject to the following requirements: 1) No copies may be sold, and 2) Excerpts must contain the full Christine Harris, M.Sc. citation of the report as follows: “Reproduced Principal Researcher and Lead Author with permission from America’s Creative Economy: Founder and CEO, Christine Harris Connections A Study of Recent Conceptions, Definitions, and Milwaukee, WI Approaches to Measurement across the USA. -

Towards a Classification of Cultural Tourists

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TOURISM RESEARCH Int. J. Tourism Res. 4, 29±38 +2002) DOI: 10.1002/jtr.346 Towards a Classi®cation of Cultural Tourists Bob McKercher* Department of Hotel and Tourism Management, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Hong Kong, SAR ABSTRACT consumer base, without considering that dif- ferent types of cultural tourists may seek This paper proposes a model to segment the qualitatively different experiences or may be cultural tourism market according to two capable of engaging attractions at different dimensions: i) the importance of cultural levels. motives in the decision to visit a destination This paper proposes a model to segment the and ii) depth of experience. The model is cultural tourism market according to two tested empirically using Hong Kong as a case dimensions: +i) the importance of cultural study. The test identi®ed ®ve discrete motives in the decision to visit a destination cultural tourism market segments that and +ii) depth of experience.The model is exhibited substantially different behaviour. tested empirically using Hong Kong as a case Copyright # 2002 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. study.The model has been proposed to advance the examination of cultural tourism as a tourism activity. Received 8 September 2000; revised 6 December 2000; accepted In this paper, terms such as shallow, deep, 12 December 2000 super®cial and meaningful are used to de- scribe different types of experiences engaged Keywords: cultural tourism; classi®cation in by cultural tourists.The terms are used as system; segmentation; Hong Kong. descriptors only; they are not used in a judgmental sense to imply that one type of INTRODUCTION activity is preferable to another or that one type of tourist is a more worthy type of cultural n spite of the fact that it has been recognised tourist than another.