Draft Introduction to Volume 49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater London Authority

Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London March 2009 Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London A report by Experian for the Greater London Authority March 2009 copyright Greater London Authority March 2009 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 84781 227 8 This publication is printed on recycled paper Experian - Business Strategies Cardinal Place 6th Floor 80 Victoria Street London SW1E 5JL T: +44 (0) 207 746 8255 F: +44 (0) 207 746 8277 This project was funded by the Greater London Authority and the London Development Agency. The views expressed in this report are those of Experian Business Strategies and do not necessarily represent those of the Greater London Authority or the London Development Agency. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................... 5 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 5 CONSUMER EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS .................................................................................... 6 CURRENT COMPARISON FLOORSPACE PROVISION ....................................................................... 9 RETAIL CENTRE TURNOVER........................................................................................................ 9 COMPARISON GOODS FLOORSPACE REQUIREMENTS -

GUNNERSBURY PARK Options Appraisal

GUNNERSBURY PARK Options Appraisal Report By Jura Consultants and LDN Architects June 2009 LDN Architects 16 Dublin Street Edinburgh EH1 3RE 0131 556 8631 JURA CONSULTANTS www.ldn.co.uk 7 Straiton View Straiton Business Park Loanhead Midlothian Edinburgh Montagu Evans LLP EH20 9QZ Clarges House 6-12 Clarges Street TEL. 0131 440 6750 London, W1J 8HB FAX. 0131 440 6751 [email protected] 020 7493 4002 www.jura-consultants.co.uk www.montagu-evans.co.uk CONTENTS Section Page Executive Summary i. 1. Introduction 1. 2. Background 5. 3. Strategic Context 17. 4. Development of Options and Scenarios 31. 5. Appraisal of Development Scenarios 43. 6. Options Development 73. 7. Enabling Development 87. 8. Preferred Option 99. 9. Conclusions and Recommendations 103. Appendix A Stakeholder Consultations Appendix B Training Opportunities Appendix C Gunnersbury Park Covenant Appendix D Other Stakeholder Organisations Appendix E Market Appraisal Appendix F Conservation Management Plan The Future of Gunnersbury Park Consultation to be conducted in the Summer of 2009 refers to Options 1, 2, 3 and 4. These options relate to the options presented in this report as follows: Report Section 6 Description Consultation Option A Minimum Intervention Option 1 Option B Mixed Use Development Option 2 Option C Restoration and Upgrading Option 4 Option D Destination Development Option 3 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction A study team led by Jura Consultants with LDN Architects and Montagu Evans was commissioned by Ealing and Hounslow Borough Councils to carry out an options appraisal for Gunnersbury Park. Gunnersbury Park is situated within the London Borough of Hounslow and is unique in being jointly owned by Ealing and Hounslow. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) a Classic Deep

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) A classic deep amber APA with fruity and refreshing flavours £4.50 Brixton Atlantic APA 5.4% (Brixton) Burst of tropical fruits for a refreshing American pale finish £4.50 INDIAN PALE ALE Mondo Kemosabe IPA 6.4% (Battersea) Dry, malty IPA, a mingle of flavours on the nose classic £4.50 Pressure Drop Mimic 6.2% (Tottenham) A rye IPA, zesty with a subtle spice £4.50 Hackney Push Eject 6.5 (Hackney) Heavily hopped, unfiltered & unfined. Hazy with tropical notes £4.50 SESSION IPA Mondo Little Victories 4.3% (Battersea) A well balanced session IPA, nice body and a hint of sweetness £4.50 LAGER Portobello Pils 4.6% (White City) Full rounded continental flavoured pilsner £3.95 Mondo All Caps 4.9% (Battersea) Corn like sweetness for this American pils £4.50 Brick Peckham Pils 4.8% (Peckham Rye) Czech style pilsner, light & refreshing £4.50 AMBER Gipsy Hill Southpaw 4.2% (Gipsy Hill) Mouthful of malt and hops meet citrus balance £4.50 SOUR Signature Jam Sour 4% (Leyton) A dry hopped raspberry sour, sharp, sweet, topical and zingy £4.50 Weird Beard Sour Slave 4% (Hanwell) Dry hopped kettle sour with a clean citrus acidity (Vg) £4.50 PALE ALE Hackney Kapow! 4.5% (Hackney) Juicy, tropical dry hopped pal. Unfiltered for bigger flavours £4.50 PORTER Bianca Road Vanilla Coffee Porter 4.5% (Bermondsey) Bitter and sweet combine with a hint of vanilla £4.50 BELGIAN & GRISETTE Structure of Matter 4.5% (Ilford) Smooth and quaffable, orangey hops, spicy and malty taste £4.50 Hello, Grisette me you’re looking for? 4.1% (Hanwell) A taste of fresh fruit salad with £4.50 a wheat serenade STOUT £4.50 Brixton Windrush Stout 5% (Brixton) Rich, chocolatey & smooth, with a creamy finish £5.00 Lord Malmölé 7.2% (Battersea) Mondo and Malmo brewery combine for this wonderful stout £4.25 Belleville Southie Stout 5.1% (Wandsworth) Rich and silky with a citrusy-herbal kick. -

Garden Show & Festival Site Report

Garden Show & Festival Site Report RHS Chelsea Flower Show Authors: Bennis 1: Key Facts Name: RHS Chelsea Flower Show (outdoors) Show Category: Built show gardens, floral displays, sales, entertainment, food Location: Royal Hospital Chelsea, London SW3 4SL UK Venue: Parkland of the hospital grounds Gross Floor Area: 11 acres (4 hectares) Dates: 20-24 May 2014; 19-23 May 2015 Origins: 1862 for the first RHS Spring Show; 1833 for first RHS flower shows; first Chelsea Flower Show 1913 Theme: Five Days that Shape the Gardening Year (more of a title than theme) Opening Times: 20-23 May 08.00-20.00; 24 May 08.00-17.30 Ticket Prices: Tuesday 20 May All day Members only £68 3.30pm Members only £38 5.30pm Members only £28 Wednesday 21 May All day Members only £58 3.30pm Members only £36 5.30pm Members only £26 Thursday 22 May All day Members £45 3.30pm Members £32 5.30pm Members £23 All Day Public £58 3.30 Public £36 5.30 Public £30 Friday 23 May All day Members £45 3.30pm Members £32 5.30pm Members £23 All Day Public £58 3.30 Public £36 5.30 Public £30 Saturday 24 May All day Members £45 All day Public £58 Charity Gala Preview: Limited numbers with champagne, canapés and music. Tickets start at £392 for individual tickets; RHS members receive a £25 discount There are no group rates and all tickets must be booked in advance; there are no ticket sales at the gate. Members can book a total of four tickets at members price Public tickets subject to £2 fee per transaction. -

Thames Path Walk Section 2 North Bank Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge

Thames Path Walk With the Thames on the right, set off along the Chelsea Embankment past Section 2 north bank the plaque to Victorian engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, who also created the Victoria and Albert Embankments. His plan reclaimed land from the Albert Bridge to Tower Bridge river to accommodate a new road with sewers beneath - until then, sewage had drained straight into the Thames and disease was rife in the city. Carry on past the junction with Royal Hospital Road, to peek into the walled garden of the Chelsea Physic Garden. Version 1 : March 2011 The Chelsea Physic Garden was founded by the Worshipful Society of Start: Albert Bridge (TQ274776) Apothecaries in 1673 to promote the study of botany in relation to medicine, Station: Clippers from Cadogan Pier or bus known at the time as the "psychic" or healing arts. As the second-oldest stops along Chelsea Embankment botanic garden in England, it still fulfils its traditional function of scientific research and plant conservation and undertakes ‘to educate and inform’. Finish: Tower Bridge (TQ336801) Station: Clippers (St Katharine’s Pier), many bus stops, or Tower Hill or Tower Gateway tube Carry on along the embankment passed gracious riverside dwellings that line the route to reach Sir Christopher Wren’s magnificent Royal Hospital Distance: 6 miles (9.5 km) Chelsea with its famous Chelsea Pensioners in their red uniforms. Introduction: Discover central London’s most famous sights along this stretch of the River Thames. The Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s The Royal Hospital Chelsea was founded in 1682 by King Charles II for the Cathedral, Tate Modern and the Tower of London, the Thames Path links 'succour and relief of veterans broken by age and war'. -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

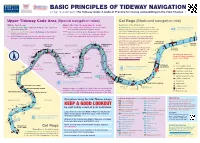

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

Battersea Area Guide

Battersea Area Guide Living in Battersea and Nine Elms Battersea is in the London Borough of Wandsworth and stands on the south bank of the River Thames, spanning from Fairfield in the west to Queenstown in the east. The area is conveniently located just 3 miles from Charing Cross and easily accessible from most parts of Central London. The skyline is dominated by Battersea Power Station and its four distinctive chimneys, visible from both land and water, making it one of London’s most famous landmarks. Battersea’s most famous attractions have been here for more than a century. The legendary Battersea Dogs and Cats Home still finds new families for abandoned pets, and Battersea Park, which opened in 1858, guarantees a wonderful day out. Today Battersea is a relatively affluent neighbourhood with wine bars and many independent and unique shops - Northcote Road once being voted London’s second favourite shopping street. The SW11 Literary Festival showcases the best of Battersea’s literary talents and the famous New Covent Garden Market keeps many of London’s restaurants supplied with fresh fruit, vegetables and flowers. Nine Elms is Europe’s largest regeneration zone and, according the mayor of London, the ‘most important urban renewal programme’ to date. Three and half times larger than the Canary Wharf finance district, the future of Nine Elms, once a rundown industrial district, is exciting with two new underground stations planned for completion by 2020 linking up with the northern line at Vauxhall and providing excellent transport links to the City, Central London and the West End. -

Introduction to the Abercorn Papers Adobe

INTRODUCTION ABERCORN PAPERS November 2007 Abercorn Papers (D623) Table of Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................2 Family history................................................................................................................3 Title deeds and leases..................................................................................................5 Irish estate papers ........................................................................................................8 Irish estate and related correspondence.....................................................................11 Scottish papers (other than title deeds) ......................................................................14 English estate papers (other than title deeds).............................................................17 Miscellaneous, mainly seventeenth-century, family papers ........................................19 Correspondence and papers of the 6th Earl of Abercorn............................................20 Correspondence and papers of the Hon. Charles Hamilton........................................21 Papers and correspondence of Capt. the Hon. John Hamilton, R.N., his widow and their son, John James, the future 1st Marquess of Abercorn....................22 Political correspondence of the 1st Marquess of Abercorn.........................................23 Political and personal correspondence of the 1st Duke of Abercorn...........................26 -

Were Celtic Identities Constructed by Archaeologists..?

Were Celtic identities constructed by archaeologists..? Tacitus (1970:62), an eye witness to the Pre-Roman Britons, wrote a non-judgmental analysis of the pre-historic inhabitants saying “it seems likely that Gauls settled in the island lying so close to their shores” and that the peoples had similar language, religious beliefs and courage. In 1705 Abbé Pezron began the construction of Celtic identity by reasoning that Celts spoke Celtic and that Edward Lhuyd added to this by assuming that the Welsh, Scots and Irish were Celtic (Collis 2006:12). James (1999:47-49) added that Lhuyd was a Welsh patriot with a political addenda for this proposal and that Lhuyd’s ideas became accepted “as established fact … with remarkable speed” and ‘Celtic’ was used to define ancient monuments and material remains. Morse (2005:9) explains that national identity of the British Isles was not a new topic and, for example, works by Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1135), John Major (1535) and George Buchanan (1582) – under the patronage of Kings and Popes - had presented different lineages for political ends linking their identity to Trojans, Druids, and Gallia Celtica. In France, supporting a growing nationalism, interest in Celtic speaking people and their achievements and, similar to England, resulted in “fanciful speculation” (Trigger 2008:89). Napoleon III, during the 1860s, to form a national culture to unite France, financially supported excavations of a Celtic town at Alésia which revealed a resemblance to the La Tène culture. During 1985, over one-hundred years later, on a nearby ancient hilltop at Bibracte President Mitterrand launched an appeal for national unity (Dietler 1994:584) claiming that this was were the “first act of our history took place”. -

Thames Tideway Tunnel

www.WaterProjectsOnline.com Wastewater Treatment & Sewerage Thames Tideway Tunnel - Central Contract technical, logistical and operational challenges have required an innovative approach to building the Super Sewer close to some of London’s biggest landmarks by Matt Jones hames Tideway Tunnel is the largest water infrastructure project currently under construction in the UK and will modernise London’s major sewerage system, the backbone of which dates back to Victorian times. Although Tthe sewers built in the mid-19th century are still in excellent structural condition, their hydraulic capacity was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette for a population and associated development of 4 million people. Continued development and population growth has resulted in the capacities of the sewer system being exceeded, so that when it rains there are combined sewer overflows (CSO) to the tidal Thames performing as planned by Bazalgette. To reduce river pollution, risk to users of the river and meet bespoke dissolved oxygen standards to protect marine wildlife, discharges from these combined sewer overflows (CSOs) must be reduced. The Environment Agency has determined that building the Tideway Tunnel in combination with the already completed Lee Tunnel and improvements at five sewage treatment works would suitably control discharges, enabling compliance with the European Union’s Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive. Visualisation showing cross section through the Thames Tideway Tunnel Central Victoria CSO site – Courtesy of Tideway Project structure and programme There is also a fourth overarching systems integrator contract The Thames Tideway Tunnel closely follows the route of the river, providing the project’s monitoring and control system. Jacobs intercepting targeted CSOs that currently discharge 18Mm3 of Engineering is the overall programme manager for Tideway.