B-163714 Questionable Basis for Approving Certain Auxiliary Route

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report

The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report January 2003 Ove Arup & Partners International Ltd Admiral House, Rose Wharf, 78 East Street, Leeds LS9 8EE Tel +44 (0)113 242 8498 Fax +44 (0)113 242 8573 REP/FI Job number 68772 The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 Scope of the Report 9 1.2 Study Background and Objectives 9 1.3 Transport Trends 10 1.4 Planning Context 10 1.5 The Integrated Transport Initiative 11 1.6 Study Approach 13 1.7 Light Rapid Transit Systems 13 2. PHASE 1 APPRAISAL 18 2.1 Introduction 18 2.2 Corridor Review 18 2.3 Development Proposals 21 2.4 The City of Edinburgh Conceptual Network 22 2.5 Priorities for Testing 23 2.6 North Edinburgh Loop 24 2.7 South Suburban Line 26 2.8 Appraisal of Long List of Corridor Schemes 29 2.9 Phase 1 Findings 47 3. APPROACH TO PHASE 2 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Technical Issues and Costs 50 3.3 Rolling Stock 54 3.4 Tram Services, Run Times and Operating Costs 55 3.5 Environmental Impact 55 3.6 Demand Forecasting 56 3.7 Appraisal 61 4. NORTH EDINBURGH LOOP 63 4.1 Alignment and Engineering Issues 63 4.2 Demand and Revenue 65 4.3 Environmental Issues 66 4.4 Integration 67 4.5 Tram Operations and Car Requirements 67 4.6 Costs 68 4.7 Appraisal 69 5. -

Guide Signs for Freeways and Expressways Are Primarily Identified by the Name of the Sign Rather Than by an Assigned Sign Designation

2011 Edition Page 235 CHAPTER 2E. GUIDE SIGNS—FREEWAYS AND EXPRESSWAYS Section 2E.01 Scope of Freeway and Expressway Guide Sign Standards Support: 01 The provisions of this Chapter provide a uniform and effective system of signing for high-volume, high- speed motor vehicle traffic on freeways and expressways. The requirements and specifications for expressway signing exceed those for conventional roads (see Chapter 2D), but are less than those for freeway signing. Since there are many geometric design variables to be found in existing roads, a signing concept commensurate with prevailing conditions is the primary consideration. Section 1A.13 includes definitions of freeway and expressway. 02 Guide signs for freeways and expressways are primarily identified by the name of the sign rather than by an assigned sign designation. Guidelines for the design of guide signs for freeways and expressways are provided in the “Standard Highway Signs and Markings” book (see Section 1A.11). Standard: 03 The provisions of this Chapter shall apply to any highway that meets the definition of freeway or expressway facilities. Section 2E.02 Freeway and Expressway Signing Principles Support: 01 The development of a signing system for freeways and expressways is approached on the premise that the signing is primarily for the benefit and direction of road users who are not familiar with the route or area. The signing furnishes road users with clear instructions for orderly progress to their destinations. Sign installations are an integral part of the facility and, as such, are best planned concurrently with the development of highway location and geometric design. -

FINAL REPORT SWLRT Engineering Evaluation of Freight Rail

Submitted to Metropolitan Council Submitted by TranSystems March 21, 2014 FINAL REPORT SWLRT Engineering Evaluation of Freight Rail Relocation Alternatives SWLRT Engineering Evaluation of Freight Rail Relocation Alternatives FINAL REPORT Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... ........... 1 II. Background ............................................................................................................................... ............ 2 A. TC&W Network and Operations ....................................................................................................... 2 B. Freight Rail Industry Changes ........................................................................................................... 4 III. Scope of Engineering Evaluation ....................................................................................................... 6 IV. Review of Past Studies ...................................................................................................................... 7 A. St. Louis Park Railroad Study (March 1999) ...................................................................................... 7 B. TCWR Freight Rail Realignment Study (November 2009) ................................................................. 7 C. Minnesota Comprehensive Statewide Freight and Passenger Rail Plan (January 2010).................. 7 D. Freight Rail Study – Evaluation of TCWR Routing Alternatives -

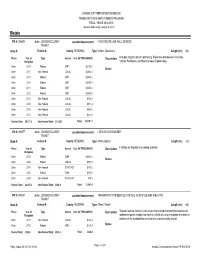

Project Listing Final

KANSAS CITY METROPOLITAN REGION TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM FISCAL YEARS 2012-2016 Revision Date: Friday, August 30, 2013 Bistate TIP #: 956004 Juris: JOHNSON COUNTY Location/Improvement: FIXED ROUTE LINE HAUL SERVICE TRANSIT State #: Federal #: County: REGIONAL Type: Vehicle Operations Length (mi): N/A Phase Year of Type Source Cost (IN THOUSANDS) Description: Includes Capital Cost of Contracting, Preventive Maintenance Activities, Obligation Vehicle Purchases, and Miscellaneous Capital Items. Other2010 Federal 5307 $2,125.0 Status: Other2011 Non-Federal LOCAL $2,062.5 Other2013 Federal 5307 $1,950.0 Other2014 Federal 5307 $1,800.0 Other2011 Federal 5307 $1,650.0 Other2012 Federal 5307 $1,650.0 Other2013 Non-Federal LOCAL $760.0 Other2010 Non-Federal LOCAL $531.3 Other2014 Non-Federal LOCAL $450.0 Other2012 Non-Federal LOCAL $412.5 Federal Total: $9,175.0 Non-Federal Total: $4,216.3 Total: $13,391.3 TIP #: 996077 Juris: JOHNSON COUNTY Location/Improvement: I-35 BUS ON SHOULDER TRANSIT State #: Federal #: County: REGIONAL Type: Other (capital) Length (mi): 19.0 Phase Year of Type Source Cost (IN THOUSANDS) Description: I-35 Bus on Shoulder and related activities Obligation Other2004 Federal 5309 $1,500.0 Status: Other2006 Federal 330-KS $397.4 Other2004 Non-Federal STATE-KS $375.0 Other2005 Federal 5309 $300.0 Other2005 Non-Federal STATE-KS $75.0 Federal Total: $2,197.4 Non-Federal Total: $450.0 Total: $2,647.4 TIP #: 996087 Juris: JOHNSON COUNTY Location/Improvement: TRANSPORTATION SERVICE FOR THE JO ROUTES 669/I AND 677/R TRANSIT State #: Federal #: County: REGIONAL Type: Other (Transit) Length (mi): N/A Phase Year of Type Source Cost (IN THOUSANDS) Description: Maintain service on two current routes that provide transportation services to Obligation welfare recipients, eligible low-income individuals, and employees who work in Other2012 Non-Federal LOCAL $124.4 portions of the metropolitan area that are underserved by transit. -

Long Range Transportation Plan 2016

LONG RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” -- Benjamin Franklin 2016 PENNSYLVANIA LONG RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Message................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Purpose of ‘PA On Track’ .................................................................................................................................................3 History of Transportation Planning in Pennsylvania .........................................................................................................4 Document Navigator ........................................................................................................................................................5 Outreach Summary ................................................................................................................................ 7 Stakeholder Involvement .................................................................................................................................................7 Public Outreach ...............................................................................................................................................................7 Planning Context ................................................................................................................................. -

RECEIVED Hon

PILLAR AND MULROY, P.C. ATTORNEYS-AT-LAW SUITE 700 312 BOULEVARD OF THE ALLIES PITTSBURGH, PA 15222 TELEPHONE (412) 471-3300 FAX: (412) 471-6068 JOHN A. PILLAR THOMAS M. MULROY December 6, IS'^O " ANTHONY A. SEETHALER, JR. Re: Transamerican Trucking Service, Inc.—Purchase (Portion)— 'Off. Nicklaus Freight Lines, Inc. File No. 1342 RECEIVED Hon. Jerry Rich, Secretary Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission DEC 81990 P. O. Box 3265 SECRETARY'S Gr-HuE Harrisburg, PA 1712 0 Public UtiJity Commission Dear Mr. Rich: We enclose herewith for filing the original and two copies of the application of Transamerican Trucking Service/ Inc. to purchase a portion of the operating rights of Nicklaus Freight Lines, Inc. The filing fee of $350.00 is also enclosed. Please acknowledge receipt on the duplicate copy of this letter of transmittal and return it to the undersigned. If any further information is required, please advise. Very, truly yours JOHN A. PILLAR sw Enclosures cc: Transamerican Trucking Service, Inc William J. Lavelle, Esq. F mm^S5 UP.-190 : Transfer ^Rev 8/88) APPLICATION FOR APPROVAL OF TRANSFER^ / ' ^ 9c AND EXERCISE OF COMMON OR CONTRACT CARRIER-RIGHTS BEFORE THE PENNSYLVANIA PUBLIC UTILITY COMMISSIQNr*-^^-*^ Application of TRANS AMERICAN TRUCKING SERVICE, INC. (Appl icant/Transferee-Buyer) for approval of the transfer and to exercise the right PUC USE ONLY as a common carrier, described at Docket Docket No. /D 1 7 1 3 (common-contract) Folder No. No. A -iO{flOl Folder No. , issued to NICKLAUS FREIGHT LINES, INC (Transferor-Seller) for transportation of property (persons-property) DEC 81990 iSECRETARY'S'OFBIGE Public utility Commission SEE INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE COMPLETING^APPLICATION ym TRANS AMERICAN TRUCKING SERVICE, INC. -

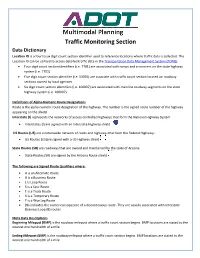

Data Dictionary Location ID Is a Four to Six Digit Count Section Identifier Used to Reference Locations Where Traffic Data Is Collected

Traffic Monitoring Section Data Dictionary Location ID is a four to six digit count section identifier used to reference locations where traffic data is collected. The Location ID can be utilized to access detailed traffic data in the Transportation Data Management System (TDMS) • Four digit count section identifiers (i.e. 7701) are associated with ramps and crossovers on the state highway system (i.e. 7701) • Five digit count section identifier (i.e. 53035) are associate with traffic count section located on roadway sections owned by local agencies • Six digit count section identifiers (i.e. 100007) are associated with mainline roadway segments on the state highway system (i.e. 100007) Definitions of Alpha-Numeric Route Designations Route is the alpha numeric route designation of the highway. The number is the signed route number of the highway appearing on the shield. Interstate (I) represents the networks of access controlled highways that form the National Highway System • Interstates (I) are signed with an Interstate Highway shield US Routes (US) are a nationwide network of roads and highways that form the Federal Highways • US Routes (US)are signed with a US Highway shield State Routes (SR) are roadways that are owned and maintained by the state of Arizona. • State Routes (SR) are signed by the Arizona Route shield The following are Signed Route Qualifiers where: • A is an Alternate Route • B is a Business Route • L Is Loop Route • S is a Spur Route • T is a Truck Route • X is a Temporary Route • Y is a Wye Leg Route • (N) indicates the numerical sequence of a discontinuous route. -

USRN Application Updated 2011

Updated August 1, 2016 American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials An Application from the State Highway or Transportation Department of North Carolina for: Elimination of a U.S. (Interstate) Route AASHTO Use Only Establishment of a U.S. (Interstate) Route I-587 (Future) Extension of a U.S. (Interstate) Route Relocation of a U.S. (Interstate) Route Establishment of a U.S. Alternate Route Establishment of a Temporary U.S. Route **Recognition of a Business Route on U.S. (Interstate) Route **Recognition of a By-Pass Route on U.S. Route Between US-64 in Zebulon (Wake County) and US-264 in Greenville (Pitt County) The following states or states are involved: North Carolina • **“Recognition of…”A local vicinity map needed on page 3. On page 6 a short statement to the effect that there are no deficiencies on proposed routing, if true, will suffice. • If there are deficiencies, they should be indicated in accordance with page 5 instructions. • All applications requesting Interstate establishment or changes are subject to concurrence and approval by the FHWA DATE SUBMITTED: September 16, 2016 SUBMIT APPLICATION ELECTRONICALLY TO [email protected] • *Bike Routes: this form is not applicable for US Bicycle Route System The purpose of the United States (U.S.) Numbered Highway System is to facilitate travel on the main interstate highways, over the shortest routes and the best available roads. A route should form continuity of available facilities through two or more states that accommodate the most important and heaviest motor traffic flow in the area. The routes comprising the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways will be marked with its own distinctive route marker shield and will have a numbering system that is separate and apart from the U.S. -

Scanned Document

SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON US ROUTE NUMBERING (USRN) ACTIVITY REPORT 2016 AMENDED 11/14/20165 Officers: Chair Mark McConnell, MS, Region 2 Members: Richard Tetreault, VT, Region 1 Mark Van Port Fleet, MI, Region 3 Joshua Laipply, CO Region 4 Marty Vitale, AASHTO, Secretary Below you will find the seven applications sent to AASHTO for review and approval from seven member departments. There will be no meeting conducted by the committee in Boston, MA. Its decisions are presented to the Standing Committee on Highways in this document and will be voted on by SCOH at its meeting on November 13, 2016 for approval and announcement to the AASHTO Board of Directors. It is important to note that all applications are examined carefully as being compliant with the purpose and policy set forth by the Standing Committee on Highways and the AASHTO Board of Directors. MEMBER DOT ROUTE Description Decision Alabama Interstate 22- Between I-65 in Birmingham, AL and Coalburg Road in 4 Approve Establish Birmingham, AL Route begins at mile marker 96.480 and the (segment) junction of I-65 in Birmingham, AL from the junction of I-65 in Birmingham, AL., westerly to Coalburg Road (Exit 93) in Birmingham, AL Traveling over existing Future Interstate 22 and continuing west to Birmingham, AL. and Jasper, AL for 2.879 miles. Route ends at mile marker 93.601 and the junction of Coalburg Road in Birmingham, AL. Idaho USBR 10- This is to address a safety issue at the intersection of Leclerc 4 Approve Realignment Road and U.S. Hwy 2 in Oldtown, ID (just east of Newport, WA), the route has been modified to now have cyclists first travel westbound to cross US 2 at a signalized intersection with ID Hwy 41 before heading eastbound on US 2 (see rows 5-9 on attachment B) Kentucky US 431- Between US 431 in Russellville and US 68 in Russellville Begins: 4 Approve Relocation US 431 originate south of Owensboro, Kentucky. -

Interstate 50Th Anniversary: the Story of Oregon's Interstates

Interstate 50th Anniversary The Story of Oregon’s Interstates Table of Contents 1) Introduction ....................................................................................................................2 2) Oregon’s road-building legacy...................................................................................... 2 3) The interstate comes to Oregon .................................................................................. 5 i) Segments of interest on I-5............................................................................. 5 ii) Focus moves to I-80N (today’s I-84) ............................................................ 6 iii) Notable segments on I-84............................................................................... 6 iv) Oregon’s minor major interstate: I-82........................................................... 7 v) Oregon’s other interstates ............................................................................... 8 vi) Oregon’s interstate segments that weren’t.................................................... 10 4) Interstate finalization chart ........................................................................................... 12 5) Interstate-related issues in Oregon .............................................................................. 12 6) Highway beautification.................................................................................................. 14 7) What’s next?....................................................................................................................16 -

Kansas Crash Data Dictionary, 2005

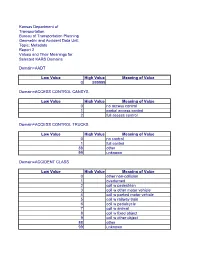

Kansas Department of Transportation Bureau of Transportation Planning Geometric and Accident Data Unit Topic: Metadata Report 2 Values and Their Meanings for Selected KARS Domains Domain=AADT Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 0 999999 Domain=ACCESS CONTROL CANSYS Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 0 no access control 1 partial access control 2 full access control Domain=ACCESS CONTROL TRUCKS Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 0 no control 1 full control 88 other 99 unknown Domain=ACCIDENT CLASS Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 0 other non-collision 1 overturned 2 coll w pedestrian 3 coll w other motor vehicle 4 coll w parked motor vehicle 5 coll w railway train 6 coll w pedalcycle 7 coll w animal 8 coll w fixed object 9 coll w other object 88 other 99 unknown Domain=ACCIDENT LOCATION Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 11 non-intersection-on roadway 12 intersection-on roadway 13 intrsection-related-on roadway 14 pklot-drvway access-on roadway 15 interchange area-on roadway 16 on crossover-on roadway 21 roadside-incl shldr-off rdwy 22 median-off roadway 23 pklot,rest area twy-off rdwy 88 other 99 unknown Domain=ACCIDENTS.ACCIDENT_KEY Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 1.99E+11 2.021E+11 Domain=ACCIDENTS.AMENDED_REPORT_IND Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 0 not amended 1 amended Domain=ACCIDENTS.CASE_STATUS Low Value High Value Meaning of Value C clean E error P passed R raw Domain=ACCIDENTS.CONTROL_SECTION Low Value High Value Meaning of Value 1 500 Domain=ACCIDENT_SUMMARY.NBR_OF_DISABLED Low Value High Value Meaning -

Response to Comments on Silver Spring to Glenmont Bikeway

Response to Comments on Silver Spring to Glenmont Bikeway CAG Member Page Comment Response Dennis The plan should indicate that over the long term there should Agreed. This was our intent but in rereading the introduction it be trails paralleling Georgia Avenue on both sides, both east is clear that this was not stated. and west. Dennis As there will likely be insufficient funds for some time to do Agreed. both, safe bike/ped crossings at every intersection on Georgia that has a traffic light should be a high priority. Dennis Suggest the Red route be modified and improved along the We agree with these comments and plan to incorporate them following lines: into our draft bikeway recommendations. 1. retain the northern section from Glenmont Metro south as far as Plyers Mill. This avoids the problems with the Wheaton CBD which may be surmountable someday, but not readily at this time. 2. Have the Red route continue along the route of the Green route east of Georgia Ave. from Plyers Mill to Forest Glen Road. This provides a safe, simple and relatively flat route without the complications and step hill that make this stretch of proposed Red line less desirable. 3. The Red route should cross Georgia at Forest Glen taking advantage of the safe bike/ped crossing that should be there. This eliminates the costly building of a new pike/ped bridge over the Beltway that the (proposed) Green line would require and allows the route to take advantage of the existing bike/ped bridge along Georgia Avenue that the proposed Blue and Red routes enjoy.