Hormonal Changes in the Menopause Transition † HENRY G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter V FOLLICULAR DYNAMICS and REPRODUCTIVE

Chapter V FOLLICULAR DYNAMICS AND REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGIES IN BUFFALO Giuseppina Maria Terzano Istituto Sperimentale per la Zootecnia (Animal Production Research Institute) Via Salaria 31, 00016 Monterotondo (Rome), Italy The general characteristics of reproduction like seasonality, cyclicity and ovulation differ widely in mammals for the following reasons: a) reproductive activity may take place during the whole year or at defined seasons, according to the species and their adaptation to environmental conditions; thus, photoperiod plays a determinant role in seasonal breeders such as rodents, carnivores and ruminants (sheep, goats, buffaloes, deer, etc.,). An extreme situation is observed in foxes with only one ovulation per year, occurring in January or February; b) mammals may be distinguished according to the absence or presence of spontaneous ovulations: in the first group of mammals ( rabbits, hares, cats, mink, camels, Llama), the ovulation is induced by mating and cyclicity is not obvious; in the second group, ovulation occurs spontaneously in each cycle, separating the follicular phase from the luteal phase; c) the length of cycles is quite different among species: small rodents have short cycles of four or five days, farm animals and primates have longer cycles (sheep: 17 days; cow, goat, buffalo, horse and pig: 21 days; primates: 28 days), and dogs are characterized by long cycles of six to seven months, including a two month luteal phase (Concannon, 1993); d) ovulation rates differ widely among species and breeds within a given species: in sheep for example, Merinos d'Arles or Ile-de-France breeds have only one ovulation per cycle, whereas average rates of two to four ovulations per cycle are observed in prolific breeds like Romanov or Finn (Land et al., 1973). -

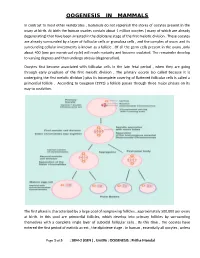

Oogenesis in Mammals

OOGENESIS IN MAMMALS In contrast to most other vertebrates , mammals do not replenish the stores of oocytes present in the ovary at birth. At birth the human ovaries contain about 1 million oocytes ( many of which are already degenerating) that have been arrested in the diplotene stage of the first meiotic division . These oocytes are already surrounded by a layer of follicular cells or granulosa cells , and the complex of ovum and its surrounding cellular investments is known as a follicle . Of all the germ cells present in the ovary ,only about 400 (one per menstrual cycle) will reach maturity and become ovulated. The remainder develop to varying degrees and then undergo atresia (degeneration). Oocytes first become associated with follicular cells in the late fetal period , when they are going through early prophase of the first meiotic division . The primary oocyte (so called because it is undergoing the first meiotic division ) plus its incomplete covering of flattened follicular cells is called a primordial follicle . According to Gougeon (1993) a follicle passes through three major phases on its way to ovulation. The first phase is characterized by a large pool of nongrowing follicles , approximately 500,000 per ovary at birth. In this pool are primordial follicles, which develop into primary follicles by surrounding themselves with a complete single layer of cuboidal follicular cells . By this time , the oocytes have entered the first period of meiotic arrest , the diplotene stage . In human , essentially all oocytes , unless Page 1 of 5 : SEM-2 (GEN ) , Unit#6 : OOGENESIS : Pritha Mondal they degenerate ,remain arrested in the diplotene stage until puberty ; some will not progress past the diplotene stage until the woman’s last reproductive cycle (age 45 to 55 years). -

Dental Considerations in Pregnancy and Menopause

J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3(2):e135-44. Pregnancy and menopause in dentistry. Journal section: Oral Medicine and Pathology doi:10.4317/jced.3.e135 Publication Types: Review Dental considerations in pregnancy and menopause Begonya Chaveli López, Mª Gracia Sarrión Pérez, Yolanda Jiménez Soriano Valencia University Medical and Dental School. Valencia (Spain) Correspondence: Apdo. de correos 24 46740 - Carcaixent (Valencia ), Spain E-mail: [email protected] Received: 01/07/2010 Accepted: 05/01/2011 Chaveli López B, Sarrión Pérez MG, Jiménez Soriano Y. Dental conside- rations in pregnancy and menopause. J Clin Exp Dent. 2011;3(2):e135-44. http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/volumenes/v3i2/jcedv3i2p135.pdf Article Number: 50348 http://www.medicinaoral.com/odo/indice.htm © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - eISSN: 1989-5488 eMail: [email protected] Abstract The present study offers a literature review of the main oral complications observed in women during pregnancy and menopause, and describes the different dental management protocols used during these periods and during lac- tation, according to the scientific literature. To this effect, a PubMed-Medline search was made, using the following key word combinations: “pregnant and dentistry”, “lactation and dentistry”, “postmenopausal and dentistry”, “me- nopausal and dentistry” and “oral bisphosphonates and dentistry”. The search was limited to reviews, metaanalyses and clinical guides in dental journals published over the last 10 years in English and Spanish. A total of 38 publi- cations were evaluated. Pregnancy can be characterized by an increased prevalence of caries and dental erosions, worsening of pre-existing gingivitis, or the appearance of pyogenic granulomas, among other problems. -

6 Ways Your Brain Transforms During Menopause

6 Ways Your Brain Transforms During Menopause By Aviva Patz Movies and TV shows have gotten a lot of laughs out of menopause, with its dramatic hot flashes and night sweats. But the midlife transition out of our reproductive years—marked by yo-yoing of hormones, mostly estrogen—is a serious quality-of-life issue for many women, and as we're now learning, may leave permanent marks on our health. "There is a critical window hypothesis in that what is done to treat the symptoms and risk factors during perimenopause predicts future health and symptoms," explains Diana Bitner, MD, assistant professor at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine and author of I Want to Age Like That: Healthy Aging Through Midlife and Menopause. "If women act on the mood changes in perimenopause and get healthy and take estrogen, the symptoms are much better immediately and also lifelong." (Going through menopause and your hormones are out of whack? Then check out The Hormone Reset Diet to balance your hormones and lose weight.) For many decades, the mantra has been that the only true menopausal symptoms are hot flashes and vaginal dryness. Certainly they're the easiest signs to spot! But we have estrogen receptors throughout the brain and body, so when estrogen levels change, we experience the repercussions all over—especially when it comes to how we think and feel. Two large studies, including one of the nation's longest longitudinal investigations, have revealed that there's a lot going on in the brain during this transition. "Before it was hard to tease out: How much of this is due to the ovaries aging and how much is due to the whole body aging?" says Pauline Maki, PhD, professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Immediate Past President of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). -

The Effectiveness and Safety of the Early Follicular Phase Full-Dose Down

The effectiveness and safety of the early follicular phase full-dose down- regulation protocol for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: a randomized, paralleled controlled, multicenter trial 2018-12-29 Background Since the first “tube baby”, Louise Brown, was born in the United Kingdom in 1978, many infertile couples have been benefitted from in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). It is reported that there are over 5 million babies born with the help of assisted reproductive technology (ART). According to the 2015 national data published by Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA, 48,147 women received 61,726 IVF/ICSI cycles and gave birth to 17,041 newborns [1]. In the United States, 169,602 IVF/ICSI cycles were performed in 2014 and 68,791 tubal babies were born [2]. China has a huge population base, and therefore has a substantial number of infertile couples. Although a late starter, China is developing rapidly in ART and playing a more and more important role in the area of reproductive medicine. In spite of the continuous development in ART, so far, the overall success rate of IVF/ICSI is still hovering around 25-40%. The live birth rate per stimulated cycle is 25.6% in the UK in 2015, fluctuating from 1.9% in women aged 45 and elder to 32.2% in women younger than 35 years old [1]. The IVF/ICSI success rate in 2014 in the US is similar [2]. In China, according to the data submitted by 115 reproductive medicine centers on the ART data reporting system developed by Chinese Society of Reproductive Medicine, the delivery rate is about 40% [3]. -

Relation of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Women Approaching Menopause

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Women’s Health Research Faculty Publications Women's Faculty Committee 2006-02-24 Relation of cardiovascular risk factors in women approaching menopause to menstrual cycle characteristics and reproductive hormones in the follicular and luteal phases Karen A. Matthews Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/wfc_pp Part of the Cardiology Commons, Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons, and the Preventive Medicine Commons Repository Citation Matthews KA, Santoro N, Lasley WL, Chang Y, Crawford SL, Pasternak RC, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Sowers M. (2006). Relation of cardiovascular risk factors in women approaching menopause to menstrual cycle characteristics and reproductive hormones in the follicular and luteal phases. Women’s Health Research Faculty Publications. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-1057. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/wfc_pp/43 This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women’s Health Research Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cardiovascular Risk Factors 1 Are the Cardiovascular Risk Factors of Women Approaching Menopause associated with Menstrual Cycle Characteristics and Reproductive Hormones in the Follicular and Luteal Phase?: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Daily Hormone Study Karen A. Matthews, PhD. 1 Nanette Santoro, MD 2, Bill Lasley, PhD. 3, Yuefang Chang, PhD. 4, Sybil Crawford, PhD. 5, Richard C. Pasternak, MD 6, Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, DrPH 4, and Mary Fran Sowers, PhD. 7 1 Departments of Psychiatry, Epidemiology and Psychology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. -

Variability in the Length of Menstrual Cycles Within and Between Women - a Review of the Evidence Key Points

Variability in the Length of Menstrual Cycles Within and Between Women - A Review of the Evidence Key Points • Mean cycle length ranges from 27.3 to 30.1 days between ages 20 and 40 years, follicular phase length is 13-15 days, and luteal phase length is less variable and averages 13-14 days1-3 • Menstrual cycle lengths vary most widely just after menarche and just before menopause primarily as cycles are anovulatory 1 • Mean length of follicular phase declines with age3,11 while luteal phase remains constant to menopause8 • The variability in menstrual cycle length is attributable to follicular phase length1,11 Introduction Follicular and luteal phase lengths Menstrual cycles are the re-occurring physiological – variability of menstrual cycle changes that happen in women of reproductive age. Menstrual cycles are counted from the first day of attributable to follicular phase menstrual flow and last until the day before the next onset of menses. It is generally assumed that the menstrual cycle lasts for 28 days, and this assumption Key Points is typically applied when dating pregnancy. However, there is variability between and within women with regard to the length of the menstrual cycle throughout • Follicular phase length averages 1,11,12 life. A woman who experiences variations of less than 8 13-15 days days between her longest and shortest cycle is considered normal. Irregular cycles are generally • Luteal phase length averages defined as having 8 to 20 days variation in length of 13-14 days1-3 cycle, whereas over 21 days variation in total cycle length is considered very irregular. -

The Evolutionary Ecology of Age at Natural Menopause

1 The Evolutionary Ecology of Age at Natural 2 Menopause: Implications for Public Health 3 4 Abigail Fraser1,3, Cathy Johnman1, Elise Whitley1, Alexandra Alvergne2,3,4 5 6 7 1 Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, UK 8 2 ISEM, Université de Montpellier, CNRS, IRD, EPHE, Montpellier, France 9 3 School of Anthropology & Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford, UK 10 4 Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford, UK 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Author for correspondence: 20 [email protected] 21 22 23 Word count: 24 Illustrations: 2 boxes; 3 figures; 1 table 25 26 27 Key words: reproductive cessation, life-history, biocultural, somatic ageing, age at 28 menopause, ovarian ageing. 29 1 30 31 Abstract 32 33 Evolutionary perspectives on menopause have focused on explaining why early 34 reproductive cessation in females has emerged and why it is rare throughout the 35 animal kingdom, but less attention has been given to exploring patterns of diversity in 36 age at natural menopause. In this paper, we aim to generate new hypotheses for 37 understanding human patterns of diversity in this trait, defined as age at final menstrual 38 period. To do so, we develop a multi-level, inter-disciplinary framework, combining 39 proximate, physiological understandings of ovarian ageing with ultimate, evolutionary 40 perspectives on ageing. We begin by reviewing known patterns of diversity in age at 41 natural menopause in humans, and highlight issues in how menopause is currently 42 defined and measured. Second, we consider together ultimate explanations of 43 menopause timing and proximate understandings of ovarian ageing. -

Trends and Patterns in Menarche in the United States: 1995 Through 2013–2017 by Gladys M

National Health Statistics Reports Number 146 September 10, 2020 Trends and Patterns in Menarche in the United States: 1995 through 2013–2017 By Gladys M. Martinez, Ph.D. Abstract older, have older friends, and be more likely to engage in negative behaviors Objective—This report presents national estimates of age at first menstrual period such as missing school, smoking, and for women aged 15–44 in the United States in 2013–2017 based on data from the drinking (8–11). The younger the age at National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Estimates for 2013–2017 are compared first menstrual period and first sexual with those from previous NSFG survey periods (1995, 2002, and 2006–2010). intercourse, the longer the interval Methods—Data for all survey periods analyzed are based on in-person interviews young women will potentially spend at with nationally representative samples of women in the household population aged risk of pregnancy. Differences in age at 15–44 in the United States. For the 2013–2017 survey period, interviews were menarche across population subgroups conducted with 10,590 female respondents aged 15–44. In 2015–2017, the age range may help explain differences in timing of the NSFG included women aged 15–49, but only those aged 15–44 were included of first sexual intercourse and timing of in this analysis. The response rate for the 2013–2017 NSFG was 67.4% for women. first births. The relationship between age Measures of menarche in this report include average age at first menstrual period, at menarche and the timing of first sexual probability of first menstrual period at each age, and the relationship between age at intercourse in the United States has menarche and age at first sexual intercourse. -

Changes Before the Change1.06 MB

Changes before the Change Perimenopausal bleeding Although some women may abruptly stop having periods leading up to the menopause, many will notice changes in patterns and irregular bleeding. Whilst this can be a natural phase in your life, it may be important to see your healthcare professional to rule out other health conditions if other worrying symptoms occur. For further information visit www.imsociety.org International Menopause Society, PO Box 751, Cornwall TR2 4WD Tel: +44 01726 884 221 Email: [email protected] Changes before the Change Perimenopausal bleeding What is menopause? Strictly defined, menopause is the last menstrual period. It defines the end of a woman’s reproductive years as her ovaries run out of eggs. Now the cells in the ovary are producing less and less hormones and menstruation eventually stops. What is perimenopause? On average, the perimenopause can last one to four years. It is the period of time preceding and just after the menopause itself. In industrialized countries, the median age of onset of the perimenopause is 47.5 years. However, this is highly variable. It is important to note that menopause itself occurs on average at age 51 and can occur between ages 45 to 55. Actually the time to one’s last menstrual period is defined as the perimenopausal transition. Often the transition can even last longer, five to seven years. What hormonal changes occur during the perimenopause? When a woman cycles, she produces two major hormones, Estrogen and Progesterone. Both of these hormones come from the cells surrounding the eggs. Estrogen is needed for the uterine lining to grow and Progesterone is produced when the egg is released at ovulation. -

Effects of Caffeine, Alcohol and Smoking on Fertility

Pre-Conception Health Special Interest Group Effects of caffeine, alcohol and smoking on fertility There is an increasing body of evidence that health behaviours affect fertility. As most health behaviours can be modified, providing advice and support in making healthy changes can promote fertility. The evidence relating to the effects on fertility of caffeine, alcohol consumption and smoking is reviewed here. Your Fertility is a national public education campaign funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing under the Family Planning Grants Program. 1 Updated October 2015 Pre-Conception Health Special Interest Group Effects of caffeine, alcohol and smoking on fertility Evidence review Caffeine Smoking Caffeine is widely consumed as it is present in coffee, tea, some soft drinks There is strong evidence that smoking adversely affects male and female and chocolate. Some evidence suggests that the consumption of caffeine, fertility. Smokers are more likely to be infertile [7, 20-21] and women with a possible dose-response effect, may prolong the time to pregnancy who are exposed to smoking take longer to conceive [22]. Furthermore, and affect the health of a developing foetus, although the mechanism for maternal smoking increases the risk of low birth weight and birth defects this is unclear. Caffeine may affect ovulation and corpus luteum functioning [23] and women who smoke reach menopause earlier than non-smokers through alterations to hormone levels [1] and has been shown to be associated [24]. Smoking can also damage sperm DNA. Heavy smoking (≥20 with elevated early follicular E2 levels in females [2]. Although some studies cigarettes per day) by fathers at the time of conception increases the have found a positive relationship between caffeine consumption and time child’s risk of childhood leukaemia and shortens reproductive lifespan to conception [3-6], study results are inconsistent and should be interpreted of daughters [25-26]. -

Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences

ISSN: 0975-8585 Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences Alcohol Affects Pregnancy by Hypothalamic- Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Derangement. Nwangwa EK1*, Ekhoye EI1, Naiho AO1, and Ekene N2. 1Department of Physiology, 2Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Delta State University, P.M.B. 001 Abraka. Delta State. Nigeria. ABSTRACT The present study investigated the deleterious effects of alcohol exposure on reproductive hormones during pregnancy. Forty Wistar albino rats (30 female & 10 male) were mated and randomized into 6 groups (n=5) and then administered with 25% alcohol daily through orogastric cannula from gestation day 0 to day 7 (Group 1), day 8 to day 14 (group 2) and day 15 to 21 (group 3). Group 4, 5 and 6 were control for 1, 2 and 3 respectively. At the end of each trimester, five rats were sacrificed from each experimental and corresponding control group and blood samples collected for FSH, LH, oestrogen and progesterone assay. The male rats were used for mating purposes only. One way analysis of Variance was used to compare means, p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. The result showed that alcohol decreased the FSH, LH, estrogen and progesterone levels during the course of the pregnancy with significance (p<0.05) especially in the third trimester. It was expected that there will be a rise in level of FSH and LH in response to decreasing oestrogen and progesterone level but that was not the case here This study therefore demonstrates that alcohol exposure adversely affects pregnancy through decrease in hormones that help in maintaining pregnancy especially in the third trimester possibly due to a derangement in the Hypothalamic- Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis.