Effects of Caffeine, Alcohol and Smoking on Fertility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Reproduction and Childbirth

8083DV HUMAN REPRODUCTION AND CHILDBIRTH DVD Version ISBN-13: 978-1-55548-681-5 ISBN: 1-55548-681-9 HUMAN REPRODUCTION AND CHILDBIRTH CREDITS Executive Producer Anson W. Schloat Producer Peter Cochran Script Karin Rhines Teacher’s Resource Book Karin Rhines Former Program Director, Westchester County (NY) Department of Health Copyright 2009 Human Relations Media, Inc. HUMAN RELATIONS MEDIA HUMAN REPRODUCTION AND CHILDBIRTH HUMAN REPRODUCTION AND CHILDBIRTH TABLE OF CONTENTS DVD Menu i Introduction 1 Learning Objectives 2 Program Summary 3 Note to the Teacher 4 Student Activities 1. Pre/Post Test 5 2. Male Anatomy 7 3. Female Anatomy 8 4. Comparative Anatomy 9 5. Matching Quiz 12 6. What Happens When? 14 7. The Fertilization Process 17 8. Care Before Birth 19 9. Research Project 20 10. Being a Parent 22 11. Stem Cells 23 Fact Sheets 1. The Menstrual Cycle 24 2. The Production of Sperm 26 3. Prenatal Care 27 4. Fetal Development 28 5. Screening Newborns for Inherited Diseases 31 6. Prenatal Pictures 32 7. Eating for Two 33 8. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome 35 9. What About Multiples? 36 10. Resources 38 11. Bibliography 39 Other Programs from Human Relations Media 40 HUMAN RELATIONS MEDIA HUMAN REPRODUCTION AND CHILDBIRTH HUMAN REPRODUCTION AND CHILDBIRTH DVD MENU MAIN MENU PLAY CHAPTER SELECTION From here you can access many different paths of the DVD, beginning with the introduction and ending with the credits. 1. Introduction 2. The Male Reproductive System 3. The Female Reproductive System 4. Fertilization and Pregnancy 5. First Trimester 6. Second and Third Trimester 7. -

Chapter V FOLLICULAR DYNAMICS and REPRODUCTIVE

Chapter V FOLLICULAR DYNAMICS AND REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGIES IN BUFFALO Giuseppina Maria Terzano Istituto Sperimentale per la Zootecnia (Animal Production Research Institute) Via Salaria 31, 00016 Monterotondo (Rome), Italy The general characteristics of reproduction like seasonality, cyclicity and ovulation differ widely in mammals for the following reasons: a) reproductive activity may take place during the whole year or at defined seasons, according to the species and their adaptation to environmental conditions; thus, photoperiod plays a determinant role in seasonal breeders such as rodents, carnivores and ruminants (sheep, goats, buffaloes, deer, etc.,). An extreme situation is observed in foxes with only one ovulation per year, occurring in January or February; b) mammals may be distinguished according to the absence or presence of spontaneous ovulations: in the first group of mammals ( rabbits, hares, cats, mink, camels, Llama), the ovulation is induced by mating and cyclicity is not obvious; in the second group, ovulation occurs spontaneously in each cycle, separating the follicular phase from the luteal phase; c) the length of cycles is quite different among species: small rodents have short cycles of four or five days, farm animals and primates have longer cycles (sheep: 17 days; cow, goat, buffalo, horse and pig: 21 days; primates: 28 days), and dogs are characterized by long cycles of six to seven months, including a two month luteal phase (Concannon, 1993); d) ovulation rates differ widely among species and breeds within a given species: in sheep for example, Merinos d'Arles or Ile-de-France breeds have only one ovulation per cycle, whereas average rates of two to four ovulations per cycle are observed in prolific breeds like Romanov or Finn (Land et al., 1973). -

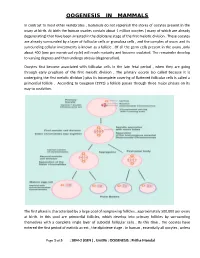

Oogenesis in Mammals

OOGENESIS IN MAMMALS In contrast to most other vertebrates , mammals do not replenish the stores of oocytes present in the ovary at birth. At birth the human ovaries contain about 1 million oocytes ( many of which are already degenerating) that have been arrested in the diplotene stage of the first meiotic division . These oocytes are already surrounded by a layer of follicular cells or granulosa cells , and the complex of ovum and its surrounding cellular investments is known as a follicle . Of all the germ cells present in the ovary ,only about 400 (one per menstrual cycle) will reach maturity and become ovulated. The remainder develop to varying degrees and then undergo atresia (degeneration). Oocytes first become associated with follicular cells in the late fetal period , when they are going through early prophase of the first meiotic division . The primary oocyte (so called because it is undergoing the first meiotic division ) plus its incomplete covering of flattened follicular cells is called a primordial follicle . According to Gougeon (1993) a follicle passes through three major phases on its way to ovulation. The first phase is characterized by a large pool of nongrowing follicles , approximately 500,000 per ovary at birth. In this pool are primordial follicles, which develop into primary follicles by surrounding themselves with a complete single layer of cuboidal follicular cells . By this time , the oocytes have entered the first period of meiotic arrest , the diplotene stage . In human , essentially all oocytes , unless Page 1 of 5 : SEM-2 (GEN ) , Unit#6 : OOGENESIS : Pritha Mondal they degenerate ,remain arrested in the diplotene stage until puberty ; some will not progress past the diplotene stage until the woman’s last reproductive cycle (age 45 to 55 years). -

World Fertility and Family Planning 2020: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/440)

World Fertility and Family Planning 2020 Highlights ST/ESA/SER.A/440 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division World Fertility and Family Planning 2020 Highlights United Nations New York, 2020 The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. The Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs provides the international community with timely and accessible population data and analysis of population trends and development outcomes for all countries and areas of the world. To this end, the Division undertakes regular studies of population size and characteristics and of all three components of population change (fertility, mortality and migration). Founded in 1946, the Population Division provides substantive support on population and development issues to the United Nations General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council and the Commission on Population and Development. It also leads or participates in various interagency coordination mechanisms of the United Nations system. -

Knowledge About Human Reproduction and Experience of Puberty 4

KNOWLEDGE ABOUT HUMAN REPRODUCTION AND EXPERIENCE OF PUBERTY 4 4.1 KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCE OF PUBERTY Knowledge of the physiology of human reproduction and the means to protect oneself against sexual or reproductive problems and diseases should be available to adolescents. Better knowledge of these subjects among young adults will lead to correct attitudes and responsible reproductive health behavior. 4.1.1 Knowledge of Physical Changes In the 2002-2003 Indonesia Young Adult Reproductive Health Survey (IYARHS), respondents were asked several questions to measure their knowledge about human reproduction and the experience of puberty. They were asked to name any physical changes that a boy or a girl goes through during the transition from childhood to adolescence. The responses were spontaneous, without any prompting from the interviewer. The findings are presented in Table 4.1. It is interesting to note that while the respondents may have experienced some of the physical changes listed in the questionnaire, some may not have recognized them as part of the process of growing up into adulthood; others may not report them to the interviewer. Table 4.1 Knowledge of physical changes at puberty Percentage of unmarried women and men age 15-24 who know of specific physical changes in a boy and a girl at puberty, by age, IYARHS 2002-2003 Women Men Indicators of physical changes 15-19 20-24 Total 15-19 20-24 Total In a boy Develop muscles 26.3 27.7 26.8 33.1 30.4 32.0 Change in voice 52.2 65.6 56.7 35.5 44.6 39.2 Growth of facial hair, pubic hair, -

The Effectiveness and Safety of the Early Follicular Phase Full-Dose Down

The effectiveness and safety of the early follicular phase full-dose down- regulation protocol for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: a randomized, paralleled controlled, multicenter trial 2018-12-29 Background Since the first “tube baby”, Louise Brown, was born in the United Kingdom in 1978, many infertile couples have been benefitted from in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). It is reported that there are over 5 million babies born with the help of assisted reproductive technology (ART). According to the 2015 national data published by Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA, 48,147 women received 61,726 IVF/ICSI cycles and gave birth to 17,041 newborns [1]. In the United States, 169,602 IVF/ICSI cycles were performed in 2014 and 68,791 tubal babies were born [2]. China has a huge population base, and therefore has a substantial number of infertile couples. Although a late starter, China is developing rapidly in ART and playing a more and more important role in the area of reproductive medicine. In spite of the continuous development in ART, so far, the overall success rate of IVF/ICSI is still hovering around 25-40%. The live birth rate per stimulated cycle is 25.6% in the UK in 2015, fluctuating from 1.9% in women aged 45 and elder to 32.2% in women younger than 35 years old [1]. The IVF/ICSI success rate in 2014 in the US is similar [2]. In China, according to the data submitted by 115 reproductive medicine centers on the ART data reporting system developed by Chinese Society of Reproductive Medicine, the delivery rate is about 40% [3]. -

Alcohol, Caffeine, and Ivf Success Pesticide Residues

E N V I R O N M E N T A N D R E P R O D U C T I V E H E A L T H ( E A R T H ) S T U D Y N E W S L E T T E R SPRING 2018 | VOL 3 HARVARD T.H. CHAN SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH, MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL ALCOHOL, CAFFEINE, AND IVF SUCCESS GREETINGS, Alcohol and caffeine have often been the focus of dietary research We are excited to share our recent findings studies on fertility. Results of these studies have been inconsistent; from the Environment and Reproductive some show benefits while others show no effect or possibly reduced Health (EARTH) Study in our 2018 newsletter! fertility. In the EARTH Study, we found that low to moderate consumption of alcohol and caffeine in the year prior to infertility It has been almost 15 years since the EARTH treatment was not associated with IVF outcomes. Our results suggest Study first began. Thanks to your that women's alcohol intake of less than one alcoholic beverage per participation, we continue to learn more day and caffeine intake below 200mg/day (less than one 12oz cup of about the impact of the environment and coffee per day) in the year prior to IVF did not affect their chances of diet on fertility and pregnancy outcomes successful fertility treatment. We also found that men’s caffeine and among couples recruited from the alcohol consumption did not affect their semen quality (Abadia et al, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Human Reproduction 2017; Karmon et al., Andrology 2017). -

Knowledge, Intentions, and Beliefs About Fertility and Assisted

KNOWLEDGE, INTENTIONS, AND BELIEFS ABOUT FERTILITY AND ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY AMONG ILLINOIS COLLEGE STUDENTS by Akilah Morris Smith B.S., Illinois State University, 2006 M.S., Illinois State University, 2008 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy Department of Public Health and Recreation Professions in the College of Education Southern Illinois University Carbondale Spring 2018 Copyright by Akilah Morris Smith, 2018 All Rights Reserved i DEDICATION I want to thank My Heavenly Father for all his guidance, support and love during this time. Thanks for challenging and blessing me. I have learned that you are authentic and real in my life. I also want to thank my mother and father Olivia and Arthur Morris for loving and supporting me unconditionally through this time. I am grateful for the best brother in the world Oheni Morris, thank you for your light heartedness, positivity and love. Thanks to my husband Wayon Smith III, son Wayon Smith IV (KJ) and in laws Mr. and Mrs. Wayon Simth Jr. and Mrs. Faye Freeman Smith for helping me during graduate school. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to my extended family and friends who listened and added valuable input during this season of my life. Special thanks to Dr. Ogletree, Dr. Wallace, Dr. Melonie Ewing, Dr. Shelby Caffey, and Dr. Diehr for their commitment in seeing me through this process. iii AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF AKILAH MORRIS SMITH, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Public Health, presented on April 11th 2018, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: KNOWLEDGE, INTENTIONS, AND BELIEFS ABOUT FERTILITY AND ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY AMONG ILLINOIS COLLEGE STUDENTS MAJOR PROFESSOR: Roberta Ogletree H.S.D and Juliane P. -

Variability in the Length of Menstrual Cycles Within and Between Women - a Review of the Evidence Key Points

Variability in the Length of Menstrual Cycles Within and Between Women - A Review of the Evidence Key Points • Mean cycle length ranges from 27.3 to 30.1 days between ages 20 and 40 years, follicular phase length is 13-15 days, and luteal phase length is less variable and averages 13-14 days1-3 • Menstrual cycle lengths vary most widely just after menarche and just before menopause primarily as cycles are anovulatory 1 • Mean length of follicular phase declines with age3,11 while luteal phase remains constant to menopause8 • The variability in menstrual cycle length is attributable to follicular phase length1,11 Introduction Follicular and luteal phase lengths Menstrual cycles are the re-occurring physiological – variability of menstrual cycle changes that happen in women of reproductive age. Menstrual cycles are counted from the first day of attributable to follicular phase menstrual flow and last until the day before the next onset of menses. It is generally assumed that the menstrual cycle lasts for 28 days, and this assumption Key Points is typically applied when dating pregnancy. However, there is variability between and within women with regard to the length of the menstrual cycle throughout • Follicular phase length averages 1,11,12 life. A woman who experiences variations of less than 8 13-15 days days between her longest and shortest cycle is considered normal. Irregular cycles are generally • Luteal phase length averages defined as having 8 to 20 days variation in length of 13-14 days1-3 cycle, whereas over 21 days variation in total cycle length is considered very irregular. -

Understanding Your Menstrual Cycle If You're Trying to Conceive

IS MY PERIOD NORMAL? Understanding Your Menstrual Cycle If You’re Trying to Conceive More than 70% 11% 95% of women have or more of of U.S. women start irregular menstrual American women their periods by cycles as menopause suffer from age 16. approaches. endometriosis.1 10% 12% of U.S. women are of women have affected by PCOS trouble getting or (polycystic ovary staying pregnant.3 syndrome).2 Fortunately, your menstrual cycle can tell you a lot about your fertility if you know what to look for. TYPES OF MENSTRUAL CYCLES Only 15% of About Normal = women have 30% of women are fertile only during 21 to 35 days the “perfect” the “normal” fertility 28-day cycle. window—between days 10 and 17 of the menstrual cycle. Day 1 Period starts (aka menses) 27 28 1 2 26 3 25 4 24 5 Day 15-28 23 6 Day 2-14 Luteal phase; Follicular phase; progesterone** 22 WHAT’S NORMAL? 7 FSH released, (follicle- uterine lining 21 8 stimulating matures Give or take a few days, hormone) and a normal cycle looks like this: estrogen released, 20 9 ovulation* begins 19 10 18 11 17 12 16 15 14 13 *ovulation: the process of an ovum (egg) being released from the ovary; occurs 10-14 days before menses. **progesterone: a steroid hormone that tells the uterus to prepare for pregnancy At least 30% of women have an “irregular” cycle either short, long or inconsistent. Short = Long = < 21 days > 35 days May be a sign of: May be a sign of: Hormonal imbalance Hormonal imbalance Ovaries with fewer eggs Lack of ovulation Approach of menopause Other fertility issues Reduced fertility4 Increased risk of miscarriage SIGNS TO WATCH FOR Your menstrual cycle provides valuable clues about your body’s reproductive health. -

Should Men Worry About Dry Orgasms? a Dry Orgasm?

The Online Resource for Sexual Health Patient Education SexHealthMatters.org is brought to you by the Sexual Medicine Society of North America, Inc. Should Men Worry About Dry Orgasms? A dry orgasm? For men, it sounds like a contradiction, doesn’t it? Men ejaculate semen at orgasm. Doesn’t that make orgasms, by definition, wet? The answer is: Not all the time. Some men reach orgasm – and feel great pleasure from it – but do not ejaculate any semen at all. Or, they might ejaculate a very small amount. This is what we mean by “dry orgasm.” While they might seem a bit unusual, dry orgasms are usually nothing to worry about. They can be a challenge for couples who would like to conceive, but they generally not a health risk. What causes dry orgasms? Men may have dry orgasms for a variety of reasons. Younger men with short refractory periods might have them occasionally. The refractory period is a period of time after orgasm during which a man’s body recovers and doesn’t respond to sexual stimulation. These intervals often don’t last long in younger men. In fact, it can be just minutes before a man is “ready to go” again. And he might climax several times during one sexual encounter. Eventually, however, the well runs dry. A man has a limited amount of semen to ejaculate and if he keeps going, that supply will be depleted. It’s not a cause for worry, though. In a day or two, the man’s body will produce semen to replace what has been ejaculated and he’ll be back to a full supply. -

Human Reproduction (Chapter- 3)

NOTES HUMAN REPRODUCTION (CHAPTER- 3) Study the following notes along with the N.C.E.R.T Practice all the diagrams in the practice register Refer to the video link at the end of the notes for a better understanding of the chapter Human beings are sexually reproducing, viviparous organisms with internal fertilization and internal development. The reproductive events in human beings include: - Gametogenesis - It is the formation of gametes through the process of meiosis inside the sex organs, that is, testis in males and ovaries in females. Gametes are called as sperms in males and ova or egg in females. - Insemination- It is the transfer of sperms from the male body into the genital tract of female. - Fertilization- It is the fusion of male and female gametes to form a diploid cell called zygote. - Cleavage- The zygote undergoes cleavage that is mitotic divisions to first form a morula and then the blastocyst. - Implantation- The blastocyst gets partially embedded in the walls of the uterus for attachment and nourishment. - Establishment of placenta- A foeto-maternal connective called Placenta develops for attachment, nutrition, respiration and excretion of embryo. - Embryonic development- The implanted embryo undergoes gastrulation (Establishment of the three primary germ layers) and then organogenesis(Development of various tissues, organs and organ systems) - Development and growth of foetus- There is growth of various parts and Systems of the foetus so that they become fully functional. The foetus is then converted into a young one and the period of total stay of embryo in the body of the mother is called gestation period (Pregnancy) - Parturition- The fully formed young one is delivered outside the mother’s body.