Supplemental Analyses for Convenience, the 42 Cov-Vips With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mouse Fscn3 Conditional Knockout Project (CRISPR/Cas9)

https://www.alphaknockout.com Mouse Fscn3 Conditional Knockout Project (CRISPR/Cas9) Objective: To create a Fscn3 conditional knockout Mouse model (C57BL/6J) by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Strategy summary: The Fscn3 gene (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_019569 ; Ensembl: ENSMUSG00000029707 ) is located on Mouse chromosome 6. 7 exons are identified, with the ATG start codon in exon 1 and the TAG stop codon in exon 6 (Transcript: ENSMUST00000031719). Exon 2 will be selected as conditional knockout region (cKO region). Deletion of this region should result in the loss of function of the Mouse Fscn3 gene. To engineer the targeting vector, homologous arms and cKO region will be generated by PCR using BAC clone RP24-176I9 as template. Cas9, gRNA and targeting vector will be co-injected into fertilized eggs for cKO Mouse production. The pups will be genotyped by PCR followed by sequencing analysis. Note: Exon 2 starts from about 9.71% of the coding region. The knockout of Exon 2 will result in frameshift of the gene. The size of intron 1 for 5'-loxP site insertion: 1817 bp, and the size of intron 2 for 3'-loxP site insertion: 839 bp. The size of effective cKO region: ~1197 bp. The cKO region does not have any other known gene. Page 1 of 7 https://www.alphaknockout.com Overview of the Targeting Strategy Wildtype allele 5' gRNA region gRNA region 3' 1 2 3 7 Targeting vector Targeted allele Constitutive KO allele (After Cre recombination) Legends Homology arm Exon of mouse Fscn3 cKO region loxP site Page 2 of 7 https://www.alphaknockout.com Overview of the Dot Plot Window size: 10 bp Forward Reverse Complement Sequence 12 Note: The sequence of homologous arms and cKO region is aligned with itself to determine if there are tandem repeats. -

Multiple Activities of Arl1 Gtpase in the Trans-Golgi Network Chia-Jung Yu1,2 and Fang-Jen S

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2017) 130, 1691-1699 doi:10.1242/jcs.201319 COMMENTARY Multiple activities of Arl1 GTPase in the trans-Golgi network Chia-Jung Yu1,2 and Fang-Jen S. Lee3,4,* ABSTRACT typical features of an Arf-family GTPase, including an amphipathic ADP-ribosylation factors (Arfs) and ADP-ribosylation factor-like N-terminal helix and a consensus site for N-myristoylation (Lu et al., proteins (Arls) are highly conserved small GTPases that function 2001; Price et al., 2005). In yeast, recruitment of Arl1 to the Golgi as main regulators of vesicular trafficking and cytoskeletal complex requires a second Arf-like GTPase, Arl3 (Behnia et al., reorganization. Arl1, the first identified member of the large Arl family, 2004; Setty et al., 2003). Yeast Arl3 lacks a myristoylation site and is an important regulator of Golgi complex structure and function in is, instead, N-terminally acetylated; this modification is required for organisms ranging from yeast to mammals. Together with its effectors, its recruitment to the Golgi complex by Sys1. In mammalian cells, Arl1 has been shown to be involved in several cellular processes, ADP-ribosylation-factor-related protein 1 (Arfrp1), a mammalian including endosomal trans-Golgi network and secretory trafficking, lipid ortholog of yeast Arl3, plays a pivotal role in the recruitment of Arl1 droplet and salivary granule formation, innate immunity and neuronal to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (Behnia et al., 2004; Panic et al., development, stress tolerance, as well as the response of the unfolded 2003b; Setty et al., 2003; Zahn et al., 2006). -

Protein Interaction Network of Alternatively Spliced Isoforms from Brain Links Genetic Risk Factors for Autism

ARTICLE Received 24 Aug 2013 | Accepted 14 Mar 2014 | Published 11 Apr 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms4650 OPEN Protein interaction network of alternatively spliced isoforms from brain links genetic risk factors for autism Roser Corominas1,*, Xinping Yang2,3,*, Guan Ning Lin1,*, Shuli Kang1,*, Yun Shen2,3, Lila Ghamsari2,3,w, Martin Broly2,3, Maria Rodriguez2,3, Stanley Tam2,3, Shelly A. Trigg2,3,w, Changyu Fan2,3, Song Yi2,3, Murat Tasan4, Irma Lemmens5, Xingyan Kuang6, Nan Zhao6, Dheeraj Malhotra7, Jacob J. Michaelson7,w, Vladimir Vacic8, Michael A. Calderwood2,3, Frederick P. Roth2,3,4, Jan Tavernier5, Steve Horvath9, Kourosh Salehi-Ashtiani2,3,w, Dmitry Korkin6, Jonathan Sebat7, David E. Hill2,3, Tong Hao2,3, Marc Vidal2,3 & Lilia M. Iakoucheva1 Increased risk for autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is attributed to hundreds of genetic loci. The convergence of ASD variants have been investigated using various approaches, including protein interactions extracted from the published literature. However, these datasets are frequently incomplete, carry biases and are limited to interactions of a single splicing isoform, which may not be expressed in the disease-relevant tissue. Here we introduce a new interactome mapping approach by experimentally identifying interactions between brain-expressed alternatively spliced variants of ASD risk factors. The Autism Spliceform Interaction Network reveals that almost half of the detected interactions and about 30% of the newly identified interacting partners represent contribution from splicing variants, emphasizing the importance of isoform networks. Isoform interactions greatly contribute to establishing direct physical connections between proteins from the de novo autism CNVs. Our findings demonstrate the critical role of spliceform networks for translating genetic knowledge into a better understanding of human diseases. -

Associated Marks Are Enriched in Imprinted Gene Regions and Predict Allele-Specific Modification

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 4, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Methods Overlapping euchromatin/heterochromatin- associated marks are enriched in imprinted gene regions and predict allele-specific modification Bo Wen,1,4 Hao Wu,2,4 Hans Bjornsson,1 Roland D. Green,3 Rafael Irizarry,2 and Andrew P. Feinberg1,5 1Department of Medicine and Center for Epigenetics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA; 2Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA; 3NimbleGen Systems, Inc., Madison, Wisconsin 53711, USA Most genome-level analysis treats the two parental alleles equivalently, yet diploid genomes contain two parental genomes that are often epigenetically distinct. While single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can be used to distinguish these genomes, it would be useful to develop a generalized strategy for identifying candidate genes or regions showing allele-specific differences, independent of SNPs. We have explored this problem by looking for overlapping marks in the genome related to both euchromatin (histone H3 dimethyl lysine-4 [H3K4Me2]) and heterochromatin (DNA methylation [DNAm]). “Double hits” were defined by the intersection of H3K4Me2 and DNAm. For the top 5% of marks, defined by a sliding window, imprinted gene regions were enriched for double hits 5.4-fold. When the location information of CTCF binding sites were integrated, the “triple hits” were enriched 76-fold for known imprinted genes in the regions studied. The double hits in imprinted genes were found to occur usually at the site of alternative or antisense transcripts. In addition, four of four imprinted genes tested showing double hits also showed allele-specific methylation. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Genome Structural Variation

Genome Structural Variation Evan Eichler Howard Hughes Medical Institute University of Washington January 18th, 2013, Comparative Genomics, Český Krumlov Disclosure: EEE was a member of the Pacific Biosciences Advisory Board (2009-2013) Genome Structural Variation Deletion Duplication Inversion Genetic Variation Types. Sequence • Single base-pair changes – point mutations • Small insertions/deletions– frameshift, microsatellite, minisatellite • Mobile elements—retroelement insertions (300bp -10 kb in size) • Large-scale genomic variation (>1 kb) – Large-scale Deletions, Inversion, translocations – Segmental Duplications • Chromosomal variation—translocations, inversions, fusions. Cytogenetics Introduction • Genome structural variation includes copy- number variation (CNV) and balanced events such as inversions and translocations—originally defined as > 1 kbp but now >50 bp • Objectives 1. Genomic architecture and disease impact. 2. Detection and characterization methods 3. Primate genome evolution Nature 455:237-41 2008 Nature 455:232-6 2008 Perspective: Segmental Duplications (SD) Definition: Continuous portion of genomic sequence represented more than once in the genome ( >90% and > 1kb in length)—a historical copy number variation Intrachromosomal Interchromosomal Distribution Interspersed Configuration Tandem Importance: Structural Variation A B C TEL A B C TEL Non Allelic Homologous Recombination GAMETES NAHR A B C A B C TEL TEL Human Disease Triplosensitive, Haploinsufficient and Imprinted Genes Calvin Bridges Alfred Sturtevant -

Supplementary Data

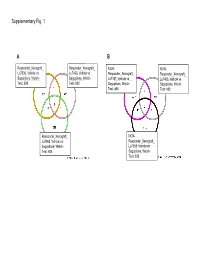

Supplementary Fig. 1 A B Responder_Xenograft_ Responder_Xenograft_ NON- NON- Lu7336, Vehicle vs Lu7466, Vehicle vs Responder_Xenograft_ Responder_Xenograft_ Sagopilone, Welch- Sagopilone, Welch- Lu7187, Vehicle vs Lu7406, Vehicle vs Test: 638 Test: 600 Sagopilone, Welch- Sagopilone, Welch- Test: 468 Test: 482 Responder_Xenograft_ NON- Lu7860, Vehicle vs Responder_Xenograft_ Sagopilone, Welch - Lu7558, Vehicle vs Test: 605 Sagopilone, Welch- Test: 333 Supplementary Fig. 2 Supplementary Fig. 3 Supplementary Figure S1. Venn diagrams comparing probe sets regulated by Sagopilone treatment (10mg/kg for 24h) between individual models (Welsh Test ellipse p-value<0.001 or 5-fold change). A Sagopilone responder models, B Sagopilone non-responder models. Supplementary Figure S2. Pathway analysis of genes regulated by Sagopilone treatment in responder xenograft models 24h after Sagopilone treatment by GeneGo Metacore; the most significant pathway map representing cell cycle/spindle assembly and chromosome separation is shown, genes upregulated by Sagopilone treatment are marked with red thermometers. Supplementary Figure S3. GeneGo Metacore pathway analysis of genes differentially expressed between Sagopilone Responder and Non-Responder models displaying –log(p-Values) of most significant pathway maps. Supplementary Tables Supplementary Table 1. Response and activity in 22 non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) xenograft models after treatment with Sagopilone and other cytotoxic agents commonly used in the management of NSCLC Tumor Model Response type -

The Function and Therapeutic Targeting of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Brandon Golding, Anita Luu, Robert Jones and Alicia M

Golding et al. Molecular Cancer (2018) 17:52 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0810-4 REVIEW Open Access The function and therapeutic targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Brandon Golding, Anita Luu, Robert Jones and Alicia M. Viloria-Petit* Abstract Lung cancer is the leading cause of death by cancer in North America. A decade ago, genomic rearrangements in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) receptor tyrosine kinase were identified in a subset of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) patients. Soon after, crizotinib, a small molecule ATP-competitive ALK inhibitor was proven to be more effective than chemotherapy in ALK-positive NSCLC patients. Crizotinib and two other ATP-competitive ALK inhibitors, ceritinib and alectinib, are approved for use as a first-line therapy in these patients, where ALK rearrangement is currently diagnosed by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. The clinical success of these three ALK inhibitors has led to the development of next-generation ALK inhibitors with even greater potency and selectivity. However, patients inevitably develop resistance to ALK inhibitors leading to tumor relapse that commonly manifests in the form of brain metastasis. Several new approaches aim to overcome the various mechanisms of resistance that develop in ALK-positive NSCLC including the knowledge-based alternate and successive use of different ALK inhibitors, as well as combined therapies targeting ALK plus alternative signaling pathways. Key issues to resolve for the optimal implementation of established and emerging treatment modalities for ALK-rearranged NSCLC therapy include the high cost of the targeted inhibitors and the potential of exacerbated toxicities with combination therapies. -

Oracle Health Sciences Omics Data Bank Programmer’S Guide Release 3.0.2.1 E35680-12

Oracle® Health Sciences Omics Data Bank Programmer’s Guide Release 3.0.2.1 E35680-12 March 2016 Oracle Health Sciences Omics Data Bank Programmer’s Guide Release 3.0.2.1 E35680-12 Copyright © 2013, 2016, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation of the programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, shall be subject to license terms and license restrictions applicable to the programs. -

39UTR Shortening Identifies High-Risk Cancers with Targeted Dysregulation

OPEN 39UTR shortening identifies high-risk SUBJECT AREAS: cancers with targeted dysregulation of GENE REGULATORY NETWORKS the ceRNA network REGULATORY NETWORKS Li Li1*, Duolin Wang2*, Mengzhu Xue1*, Xianqiang Mi1, Yanchun Liang2 & Peng Wang1,3 Received 1 2 15 April 2014 Key Laboratory of Systems Biology, Shanghai Advanced Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, College of Computer Science and Technology, Jilin University, 3School of Life Science and Technology, ShanghaiTech University. Accepted 3 June 2014 Competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) interactions form a multilayered network that regulates gene Published expression in various biological pathways. Recent studies have demonstrated novel roles of ceRNA 23 June 2014 interactions in tumorigenesis, but the dynamics of the ceRNA network in cancer remain unexplored. Here, we examine ceRNA network dynamics in prostate cancer from the perspective of alternative cleavage and polyadenylation (APA) and reveal the principles of such changes. Analysis of exon array data revealed that both shortened and lengthened 39UTRs are abundant. Consensus clustering with APA data stratified Correspondence and cancers into groups with differing risks of biochemical relapse and revealed that a ceRNA subnetwork requests for materials enriched with cancer genes was specifically dysregulated in high-risk cancers. The novel connection between should be addressed to 39UTR shortening and ceRNA network dysregulation was supported by the unusually high number of P.W. (wangpeng@ microRNA response elements (MREs) shared by the dysregulated ceRNA interactions and the significantly sari.ac.cn) altered 39UTRs. The dysregulation followed a fundamental principle in that ceRNA interactions connecting genes that show opposite trends in expression change are preferentially dysregulated. This targeted dysregulation is responsible for the majority of the observed expression changes in genes with significant * These authors ceRNA dysregulation and represents a novel mechanism underlying aberrant oncogenic expression. -

A SARS-Cov-2 Protein Interaction Map Reveals Targets for Drug Repurposing

Article A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9 A list of authors and affiliations appears at the end of the paper Received: 23 March 2020 Accepted: 22 April 2020 A newly described coronavirus named severe acute respiratory syndrome Published online: 30 April 2020 coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has infected over 2.3 million people, led to the death of more than Check for updates 160,000 individuals and caused worldwide social and economic disruption1,2. There are no antiviral drugs with proven clinical efcacy for the treatment of COVID-19, nor are there any vaccines that prevent infection with SARS-CoV-2, and eforts to develop drugs and vaccines are hampered by the limited knowledge of the molecular details of how SARS-CoV-2 infects cells. Here we cloned, tagged and expressed 26 of the 29 SARS-CoV-2 proteins in human cells and identifed the human proteins that physically associated with each of the SARS-CoV-2 proteins using afnity-purifcation mass spectrometry, identifying 332 high-confdence protein–protein interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and human proteins. Among these, we identify 66 druggable human proteins or host factors targeted by 69 compounds (of which, 29 drugs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, 12 are in clinical trials and 28 are preclinical compounds). We screened a subset of these in multiple viral assays and found two sets of pharmacological agents that displayed antiviral activity: inhibitors of mRNA translation and predicted regulators of the sigma-1 and sigma-2 receptors. -

The Transcriptional Roles of ALK Fusion Proteins in Tumorigenesis

cancers Review The Transcriptional Roles of ALK Fusion Proteins in Tumorigenesis 1, 2, , 1, Stephen P. Ducray y , Karthikraj Natarajan y z, Gavin D. Garland z, 1, , 2,3, , Suzanne D. Turner * y and Gerda Egger * y 1 Division of Cellular and Molecular Pathology, Department of Pathology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB20QQ, UK 2 Department of Pathology, Medical University Vienna, 1090 Vienna, Austria 3 Ludwig Boltzmann Institute Applied Diagnostics, 1090 Vienna, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.D.T.); [email protected] (G.E.) European Research Initiative for ALK-related malignancies; www.erialcl.net. y These authors contributed equally to this work. z Received: 7 June 2019; Accepted: 23 July 2019; Published: 30 July 2019 Abstract: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is a tyrosine kinase involved in neuronal and gut development. Initially discovered in T cell lymphoma, ALK is frequently affected in diverse cancers by oncogenic translocations. These translocations involve different fusion partners that facilitate multimerisation and autophosphorylation of ALK, resulting in a constitutively active tyrosine kinase with oncogenic potential. ALK fusion proteins are involved in diverse cellular signalling pathways, such as Ras/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and Janus protein tyrosine kinase (JAK)/STAT. Furthermore, ALK is implicated in epigenetic regulation, including DNA methylation and miRNA expression, and an interaction with nuclear proteins has been described. Through these mechanisms, ALK fusion proteins enable a transcriptional programme that drives the pathogenesis of a range of ALK-related malignancies. Keywords: ALK; ALCL; NPM-ALK; EML4-ALK; NSCLC; ALK-translocation proteins; epigenetics 1. Introduction Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) was first successfully cloned in 1994 when it was reported in the context of a fusion protein in cases of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) [1].