Non-Canonical Thinking for Targeting ALK-Fusion Onco-Proteins in Lung Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiple Activities of Arl1 Gtpase in the Trans-Golgi Network Chia-Jung Yu1,2 and Fang-Jen S

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2017) 130, 1691-1699 doi:10.1242/jcs.201319 COMMENTARY Multiple activities of Arl1 GTPase in the trans-Golgi network Chia-Jung Yu1,2 and Fang-Jen S. Lee3,4,* ABSTRACT typical features of an Arf-family GTPase, including an amphipathic ADP-ribosylation factors (Arfs) and ADP-ribosylation factor-like N-terminal helix and a consensus site for N-myristoylation (Lu et al., proteins (Arls) are highly conserved small GTPases that function 2001; Price et al., 2005). In yeast, recruitment of Arl1 to the Golgi as main regulators of vesicular trafficking and cytoskeletal complex requires a second Arf-like GTPase, Arl3 (Behnia et al., reorganization. Arl1, the first identified member of the large Arl family, 2004; Setty et al., 2003). Yeast Arl3 lacks a myristoylation site and is an important regulator of Golgi complex structure and function in is, instead, N-terminally acetylated; this modification is required for organisms ranging from yeast to mammals. Together with its effectors, its recruitment to the Golgi complex by Sys1. In mammalian cells, Arl1 has been shown to be involved in several cellular processes, ADP-ribosylation-factor-related protein 1 (Arfrp1), a mammalian including endosomal trans-Golgi network and secretory trafficking, lipid ortholog of yeast Arl3, plays a pivotal role in the recruitment of Arl1 droplet and salivary granule formation, innate immunity and neuronal to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (Behnia et al., 2004; Panic et al., development, stress tolerance, as well as the response of the unfolded 2003b; Setty et al., 2003; Zahn et al., 2006). -

Discovery and Optimization of Selective Inhibitors of Meprin Α (Part II)

pharmaceuticals Article Discovery and Optimization of Selective Inhibitors of Meprin α (Part II) Chao Wang 1,2, Juan Diez 3, Hajeung Park 1, Christoph Becker-Pauly 4 , Gregg B. Fields 5 , Timothy P. Spicer 1,6, Louis D. Scampavia 1,6, Dmitriy Minond 2,7 and Thomas D. Bannister 1,2,* 1 Department of Molecular Medicine, Scripps Research, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA; [email protected] (C.W.); [email protected] (H.P.); [email protected] (T.P.S.); [email protected] (L.D.S.) 2 Department of Chemistry, Scripps Research, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA; [email protected] 3 Rumbaugh-Goodwin Institute for Cancer Research, Nova Southeastern University, 3321 College Avenue, CCR r.605, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314, USA; [email protected] 4 The Scripps Research Molecular Screening Center, Scripps Research, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA; [email protected] 5 Unit for Degradomics of the Protease Web, Institute of Biochemistry, University of Kiel, Rudolf-Höber-Str.1, 24118 Kiel, Germany; fi[email protected] 6 Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry and I-HEALTH, Florida Atlantic University, 5353 Parkside Drive, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA 7 Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine, Nova Southeastern University, 3301 College Avenue, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Meprin α is a zinc metalloproteinase (metzincin) that has been implicated in multiple diseases, including fibrosis and cancers. It has proven difficult to find small molecules that are capable Citation: Wang, C.; Diez, J.; Park, H.; of selectively inhibiting meprin α, or its close relative meprin β, over numerous other metzincins Becker-Pauly, C.; Fields, G.B.; Spicer, which, if inhibited, would elicit unwanted effects. -

Structural Basis for the Sheddase Function of Human Meprin Β Metalloproteinase at the Plasma Membrane

Structural basis for the sheddase function of human meprin β metalloproteinase at the plasma membrane Joan L. Arolasa, Claudia Broderb, Tamara Jeffersonb, Tibisay Guevaraa, Erwin E. Sterchic, Wolfram Boded, Walter Stöckere, Christoph Becker-Paulyb, and F. Xavier Gomis-Rütha,1 aProteolysis Laboratory, Department of Structural Biology, Molecular Biology Institute of Barcelona, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Barcelona Science Park, E-08028 Barcelona, Spain; bInstitute of Biochemistry, Unit for Degradomics of the Protease Web, University of Kiel, D-24118 Kiel, Germany; cInstitute of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, University of Berne, CH-3012 Berne, Switzerland; dArbeitsgruppe Proteinaseforschung, Max-Planck-Institute für Biochemie, D-82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany; and eInstitute of Zoology, Cell and Matrix Biology, Johannes Gutenberg-University, D-55128 Mainz, Germany Edited by Brian W. Matthews, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, and approved August 22, 2012 (received for review June 29, 2012) Ectodomain shedding at the cell surface is a major mechanism to proteolysis” step within the membrane (1). This is the case for the regulate the extracellular and circulatory concentration or the processing of Notch ligand Delta1 and of APP, both carried out by activities of signaling proteins at the plasma membrane. Human γ-secretase after action of an α/β-secretase (11), and for signal- meprin β is a 145-kDa disulfide-linked homodimeric multidomain peptide peptidase, which removes remnants of the secretory pro- type-I membrane metallopeptidase that sheds membrane-bound tein translocation from the endoplasmic membrane (13). cytokines and growth factors, thereby contributing to inflammatory Recently, human meprin β (Mβ) was found to specifically pro- diseases, angiogenesis, and tumor progression. -

Metalloproteases Meprin Α and Meprin Β Are C- and N-Procollagen Proteinases Important for Collagen Assembly and Tensile Strength

Metalloproteases meprin α and meprin β are C- and N-procollagen proteinases important for collagen assembly and tensile strength Claudia Brodera, Philipp Arnoldb, Sandrine Vadon-Le Goffc, Moritz A. Konerdingd, Kerstin Bahrd, Stefan Müllere, Christopher M. Overallf, Judith S. Bondg, Tomas Koudelkah, Andreas Tholeyh, David J. S. Hulmesc, Catherine Moalic, and Christoph Becker-Paulya,1 aUnit for Degradomics of the Protease Web, Institute of Biochemistry, University of Kiel, 24118 Kiel, Germany; bInstitute of Zoology, Johannes Gutenberg University, 55128 Mainz, Germany; cTissue Biology and Therapeutic Engineering Unit, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique/University of Lyon, Unité Mixte de Recherche 5305, Unité Mixte de Service 3444 Biosciences Gerland-Lyon Sud, 69367 Lyon Cedex 7, France; dInstitute of Functional and Clinical Anatomy, University Medical Center, Johannes Gutenberg University, 55128 Mainz, Germany; eDepartment of Gastroenterology, University of Bern, CH-3010 Bern, Switzerland; fCentre for Blood Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z3; gDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA 17033; and hInstitute of Experimental Medicine, University of Kiel, 24118 Kiel, Germany Edited by Robert Huber, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany, and approved July 9, 2013 (received for review March 22, 2013) Type I fibrillar collagen is the most abundant protein in the human formation (22). A tight balance between synthesis and break- body, crucial for the formation and strength of bones, skin, and down of ECM is required for the function of all tissues, and tendon. Proteolytic enzymes are essential for initiation of the dysregulation leads to pathophysiological events, such as arthri- assembly of collagen fibrils by cleaving off the propeptides. -

Src Activation Plays an Important Key Role in Lymphomagenesis Induced by FGFR1 Fusion Kinases

Published OnlineFirst September 21, 2011; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1109 Cancer Tumor and Stem Cell Biology Research Src Activation Plays an Important Key Role in Lymphomagenesis Induced by FGFR1 Fusion Kinases Mingqiang Ren, Haiyan Qin, Ruizhe Ren, Josephine Tidwell, and John K. Cowell Abstract Chromosomal translocations and activation of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 1 (FGFR1) are a feature of stem cell leukemia–lymphoma syndrome (SCLL), an aggressive malignancy characterized by rapid transformation to acute myeloid leukemia and lymphoblastic lymphoma. It has been suggested that FGFR1 proteins lose their ability to recruit Src kinase, an important mediator of FGFR1 signaling, as a result of the translocations that delete the extended FGFR substrate-2 (FRS2) interacting domain that Src binds. In this study, we report evidence that refutes this hypothesis and reinforces the notion that Src is a critical mediator of signaling from the FGFR1 chimeric fusion genes generated by translocation in SCLL. Src was constitutively active in BaF3 cells expressing exogenous FGFR1 chimeric kinases cultured in vitro as well as in T-cell or B-cell lymphomas they induced in vivo. Residual components of the FRS2-binding site retained in chimeric kinases that were generated by translocation were sufficient to interact with FRS2 and activate Src. The Src kinase inhibitor dasatinib killed transformed BaF3 cells and other established murine leukemia cell lines expressing chimeric FGFR1 kinases, significantly extending the survival of mice with SCLL syndrome. Our results indicated that Src kinase is pathogenically activated in lymphomagenesis induced by FGFR1 fusion genes, implying that Src kinase inhibitors may offer a useful option to treatment of FGFR1-associated myeloproliferative/lymphoma disorders. -

FGF Signaling Network in the Gastrointestinal Tract (Review)

163-168 1/6/06 16:12 Page 163 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY 29: 163-168, 2006 163 FGF signaling network in the gastrointestinal tract (Review) MASUKO KATOH1 and MASARU KATOH2 1M&M Medical BioInformatics, Hongo 113-0033; 2Genetics and Cell Biology Section, National Cancer Center Research Institute, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan Received March 29, 2006; Accepted May 2, 2006 Abstract. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signals are trans- Contents duced through FGF receptors (FGFRs) and FRS2/FRS3- SHP2 (PTPN11)-GRB2 docking protein complex to SOS- 1. Introduction RAS-RAF-MAPKK-MAPK signaling cascade and GAB1/ 2. FGF family GAB2-PI3K-PDK-AKT/aPKC signaling cascade. The RAS~ 3. Regulation of FGF signaling by WNT MAPK signaling cascade is implicated in cell growth and 4. FGF signaling network in the stomach differentiation, the PI3K~AKT signaling cascade in cell 5. FGF signaling network in the colon survival and cell fate determination, and the PI3K~aPKC 6. Clinical application of FGF signaling cascade in cell polarity control. FGF18, FGF20 and 7. Clinical application of FGF signaling inhibitors SPRY4 are potent targets of the canonical WNT signaling 8. Perspectives pathway in the gastrointestinal tract. SPRY4 is the FGF signaling inhibitor functioning as negative feedback apparatus for the WNT/FGF-dependent epithelial proliferation. 1. Introduction Recombinant FGF7 and FGF20 proteins are applicable for treatment of chemotherapy/radiation-induced mucosal injury, Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family proteins play key roles while recombinant FGF2 protein and FGF4 expression vector in growth and survival of stem cells during embryogenesis, are applicable for therapeutic angiogenesis. Helicobacter tissues regeneration, and carcinogenesis (1-4). -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown Et Al

US 20030082511A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2003/0082511 A1 Brown et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 1, 2003 (54) IDENTIFICATION OF MODULATORY Publication Classification MOLECULES USING INDUCIBLE PROMOTERS (51) Int. Cl." ............................... C12O 1/00; C12O 1/68 (52) U.S. Cl. ..................................................... 435/4; 435/6 (76) Inventors: Steven J. Brown, San Diego, CA (US); Damien J. Dunnington, San Diego, CA (US); Imran Clark, San Diego, CA (57) ABSTRACT (US) Correspondence Address: Methods for identifying an ion channel modulator, a target David B. Waller & Associates membrane receptor modulator molecule, and other modula 5677 Oberlin Drive tory molecules are disclosed, as well as cells and vectors for Suit 214 use in those methods. A polynucleotide encoding target is San Diego, CA 92121 (US) provided in a cell under control of an inducible promoter, and candidate modulatory molecules are contacted with the (21) Appl. No.: 09/965,201 cell after induction of the promoter to ascertain whether a change in a measurable physiological parameter occurs as a (22) Filed: Sep. 25, 2001 result of the candidate modulatory molecule. Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 1 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 cDNA F.G. 1 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 2 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 49 - -9 G C EH H EH N t R M h so as se W M M MP N FIG.2 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 3 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 FG. 3 Patent Application Publication May 1, 2003 Sheet 4 of 8 US 2003/0082511 A1 KCNC1 ITREXCHO KC 150 mM KC 2000000 so 100 mM induced Uninduced Steady state O 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 Time (seconds) FIG. -

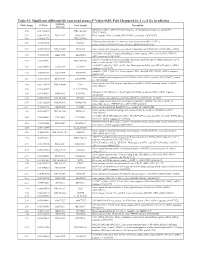

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Genome Structural Variation

Genome Structural Variation Evan Eichler Howard Hughes Medical Institute University of Washington January 18th, 2013, Comparative Genomics, Český Krumlov Disclosure: EEE was a member of the Pacific Biosciences Advisory Board (2009-2013) Genome Structural Variation Deletion Duplication Inversion Genetic Variation Types. Sequence • Single base-pair changes – point mutations • Small insertions/deletions– frameshift, microsatellite, minisatellite • Mobile elements—retroelement insertions (300bp -10 kb in size) • Large-scale genomic variation (>1 kb) – Large-scale Deletions, Inversion, translocations – Segmental Duplications • Chromosomal variation—translocations, inversions, fusions. Cytogenetics Introduction • Genome structural variation includes copy- number variation (CNV) and balanced events such as inversions and translocations—originally defined as > 1 kbp but now >50 bp • Objectives 1. Genomic architecture and disease impact. 2. Detection and characterization methods 3. Primate genome evolution Nature 455:237-41 2008 Nature 455:232-6 2008 Perspective: Segmental Duplications (SD) Definition: Continuous portion of genomic sequence represented more than once in the genome ( >90% and > 1kb in length)—a historical copy number variation Intrachromosomal Interchromosomal Distribution Interspersed Configuration Tandem Importance: Structural Variation A B C TEL A B C TEL Non Allelic Homologous Recombination GAMETES NAHR A B C A B C TEL TEL Human Disease Triplosensitive, Haploinsufficient and Imprinted Genes Calvin Bridges Alfred Sturtevant -

Integrated Genetic and Epigenetic Analysis Defines Novel Molecular

ARTICLE Received 7 Jan 2015 | Accepted 20 May 2015 | Published 3 Jul 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8557 OPEN Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis defines novel molecular subgroups in rhabdomyosarcoma Masafumi Seki1,*, Riki Nishimura1,*, Kenichi Yoshida2,3, Teppei Shimamura4,5, Yuichi Shiraishi4, Yusuke Sato2,3, Motohiro Kato1,6,7, Kenichi Chiba4, Hiroko Tanaka8, Noriko Hoshino9, Genta Nagae10, Yusuke Shiozawa2,3, Yusuke Okuno3,11, Hajime Hosoi12, Yukichi Tanaka13, Hajime Okita14, Mitsuru Miyachi12, Ryota Souzaki15, Tomoaki Taguchi15, Katsuyoshi Koh7, Ryoji Hanada7, Keisuke Kato16, Yuko Nomura17, Masaharu Akiyama18, Akira Oka1, Takashi Igarashi1,19, Satoru Miyano4,8, Hiroyuki Aburatani10, Yasuhide Hayashi20, Seishi Ogawa2,3 & Junko Takita1 Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft-tissue sarcoma in childhood. Here we studied 60 RMSs using whole-exome/-transcriptome sequencing, copy number (CN) and DNA methylome analyses to unravel the genetic/epigenetic basis of RMS. On the basis of methylation patterns, RMS is clustered into four distinct subtypes, which exhibits remarkable correlation with mutation/CN profiles, histological phenotypes and clinical behaviours. A1 and A2 subtypes, especially A1, largely correspond to alveolar histology with frequent PAX3/7 fusions and alterations in cell cycle regulators. In contrast, mostly showing embryonal histology, both E1 and E2 subtypes are characterized by high frequency of CN alterations and/ or allelic imbalances, FGFR4/RAS/AKT pathway mutations and PTEN mutations/methylation and in E2, also by p53 inactivation. Despite the better prognosis of embryonal RMS, patients in the E2 are likely to have a poor prognosis. Our results highlight the close relationships of the methylation status and gene mutations with the biological behaviour in RMS. -

Flotillins in Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling and Cancer

Cells 2014, 3, 129-149; doi:10.3390/cells3010129 OPEN ACCESS cells ISSN 2073-4409 www.mdpi.com/journal/cells Review Flotillins in Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling and Cancer Antje Banning, Nina Kurrle †, Melanie Meister and Ritva Tikkanen * Institute of Biochemistry, Medical faculty, University of Giessen, Friedrichstrasse 24, 35392 Giessen, Germany; E-Mails: [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (N.K.); [email protected] (M.M.) † Present address: Department of Molecular Haematology, Goethe University Medical School, 60590 Frankfurt, Germany. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-641-9947-420; Fax: +49-641-9947-429. Received: 11 December 2013; in revised form: 11 February 2014 / Accepted: 12 February 2014/ Published: 19 February 2014 Abstract: Flotillins are highly conserved proteins that localize into specific cholesterol rich microdomains in cellular membranes. They have been shown to be associated with, for example, various signaling pathways, cell adhesion, membrane trafficking and axonal growth. Recent findings have revealed that flotillins are frequently overexpressed in various types of human cancers. We here review the suggested functions of flotillins during receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and in cancer. Although flotillins have been implicated as putative cancer therapy targets, we here show that great caution is required since flotillin ablation may result in effects that increase instead of decrease the activity of specific signaling pathways. On the other hand, as flotillin overexpression appears to be related with metastasis formation in certain cancers, we also discuss the implications of these findings for future therapy aspects. -

"The Genecards Suite: from Gene Data Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses". In: Current Protocols in Bioinformat

The GeneCards Suite: From Gene Data UNIT 1.30 Mining to Disease Genome Sequence Analyses Gil Stelzer,1,5 Naomi Rosen,1,5 Inbar Plaschkes,1,2 Shahar Zimmerman,1 Michal Twik,1 Simon Fishilevich,1 Tsippi Iny Stein,1 Ron Nudel,1 Iris Lieder,2 Yaron Mazor,2 Sergey Kaplan,2 Dvir Dahary,2,4 David Warshawsky,3 Yaron Guan-Golan,3 Asher Kohn,3 Noa Rappaport,1 Marilyn Safran,1 and Doron Lancet1,6 1Department of Molecular Genetics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel 2LifeMap Sciences Ltd., Tel Aviv, Israel 3LifeMap Sciences Inc., Marshfield, Massachusetts 4Toldot Genetics Ltd., Hod Hasharon, Israel 5These authors contributed equally to the paper 6Corresponding author GeneCards, the human gene compendium, enables researchers to effectively navigate and inter-relate the wide universe of human genes, diseases, variants, proteins, cells, and biological pathways. Our recently launched Version 4 has a revamped infrastructure facilitating faster data updates, better-targeted data queries, and friendlier user experience. It also provides a stronger foundation for the GeneCards suite of companion databases and analysis tools. Improved data unification includes gene-disease links via MalaCards and merged biological pathways via PathCards, as well as drug information and proteome expression. VarElect, another suite member, is a phenotype prioritizer for next-generation sequencing, leveraging the GeneCards and MalaCards knowledgebase. It au- tomatically infers direct and indirect scored associations between hundreds or even thousands of variant-containing genes and disease phenotype terms. Var- Elect’s capabilities, either independently or within TGex, our comprehensive variant analysis pipeline, help prepare for the challenge of clinical projects that involve thousands of exome/genome NGS analyses.