CDC Ebola Response Oral History Project the Reminiscences Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin November, 17 (English)

VAID’S ICS LUCKNOW B-36, Sector-C, Aliganj, Lucknow Cont.9415011892/93 NOVEMBER-2017 Vaid’s ICS Lucknow B-36, Sector –C, Aliganj, Lucknow Mob: 9415011892/93, 8765163028 website: www.vaidicslucknow.com 1 VAID’S ICS LUCKNOW B-36, Sector-C, Aliganj, Lucknow Cont.9415011892/93 Content Pages 1. National Events 3 2. International Events 7 3. Economy 11 4. Science & Technology 14 5. Treaty & Agreements 16 6. Planning & Project 19 7. Conference 20 8. Sports 23 9. Awards & Honours 26 10. Persons in news 28 11. Places in news 29 12. Commissions & Committee 31 13. Operations & Campaign 32 14. Associations & Organizations 33 15. Law & Justice 34 16. Year, Day & Week 35 16. Miscellaneous 38 2 VAID’S ICS LUCKNOW B-36, Sector-C, Aliganj, Lucknow Cont.9415011892/93 • In the year 2014, 14.5 percent of the total NATIONAL EVENTS cases of crimes against women (49,262 cases) were held in Uttar Pradesh. After this, West Crime in India 2016- Statistics Bengal is at second with 9.6 percent (32,513) th • On November 30 , 2017, Union Home cases. Minister, Shri Rajnath Singh released the • Rape incidents rose 12.4 percent in the year ‘Crime in India – 2016’ published by the 2016 compared to year 2015. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), • According to the Reports, the highest rape Ministry of Home Affairs. cases took place in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar • It is for the first time, for 19 Metropolitan Pradesh. cities (having population above 2 million) also, • Out of total incidents, 12.5 percent were in chapters on “Violent Crimes”,” Crime Against Madhya Pradesh, 12.4 percent in UP and 10.7 Women”,” Crime Against Children”, “Juveniles percent in Maharashtra. -

Changing Kenya's Literary Landscape

CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE Part 2: Past, Present & Future A research paper by Alex Nderitu (www.AlexanderNderitu.com) 09/07/2014 Nairobi, Kenya 1 CHANGING KENYA’S LITERARY LANDSCAPE Contents: 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 2. Writers in Politics ........................................................................................................ 6 3. A Brief Look at Swahili Literature ....................................................................... 70 - A Taste of Culture - Origins of Kiswahili Lit - Modern Times - The Case for Kiswahili as Africa’s Lingua Franca - Africa the Beautiful 4. JEREMIAH’S WATERS: Why Are So Many Writers Drunkards? ................ 89 5. On Writing ................................................................................................................... 97 - The Greats - The Plot Thickens - Crime & Punishment - Kenyan Scribes 6. Scribbling Rivalry: Writing Families ............................................................... 122 7. Crazy Like a Fox: Humour Writing ................................................................... 128 8. HIGHER LEARNING: Do Universities Kill by Degrees? .............................. 154 - The River Between - Killing Creativity/Entreprenuership - The Importance of Education - Knife to a Gunfight - The Storytelling Gift - The Colour Purple - The Importance of Editors - The Kids are Alright - Kidneys for the King -

Tribune 25 Template V2009

C M C M Y K Y K WEATHER ! EW N McCOMBO OF THE DAY HIGH 84F THE PEOPLE’S PAPER – BIGGEST AND BEST LOW 74F The Tribune PARTLY SUNNY, T-STORM BAHAMAS EDITION www.tribune242.com Volume: 106 No.286 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 2010 PRICE – 75¢ (Abaco and Grand Bahama $1.25) CARS FOR SALE, S Perfect E Bootie S E R T D HELP WANTED U I R T S O A N P I E licious AND REAL ESTATE record! S F SEE WOMAN SECTION BAHAMAS BIGGEST SEE PAGE TWELVE Priest admits intimacy with fire death woman Deceased made MANGROVE CAY HIGH SCHOOL HITS THE HIGH NOTES rector beneficiary on life insurance A CATHOLIC priest before she died, but does admitted yesterday he was not remember how he got intimately involved with a home. woman who died in a fire at He claimed his last coher- her apartment four years ent memory was of eating a ago – the same day he had bowl of souse at the wom- to be pulled from a separate an’s apartment. blaze at his own home. Fr Cooper described his During the continuation relationship with the of the coroner’s inquest into deceased as “abnormal” the death of 35-year-old considering his vow of hotel worker Nicola Gibson, chastity, and revealed that Father David Cooper took Ms Gibson had made him a the stand, claiming he visited the deceased on the night SEE page 10 f f a t s e n Shooting leaves man in hospital u b i r POLICE are investigating a shooting that has left one man in T / e hospital. -

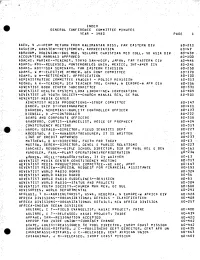

Index General Conference Committee Minutes Year - 1980� Page �2

INDEX GENERAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE MINUTES YEAR - 1980 PAGE 1 AAEN, A J--PERM RETURN FROM KALJMANTAN MISS, FAR EASTERN DIV . 80-211 AASEIIM, KARSTEN--RETIPEMENT, APPRECIATION 80-47 ABRAHAM, ROBINSON--BUS MGR, VELLORE CHRISTIAN MED COLL, SO ASIA DIV 80-439 - ACCOUNTING MANUALS APPROVED 80710.0 ADACHI, MARIKO--TEACHER, TOKYO SAN-HOSP, JAPAN, FAR EASTERN CIV '80;1,46 ADAMS4. Rty—RELEASED,' mONTEMORELOS UNIV, MEXICO, INT-AmER Ell 80-241 ADAMS, ROY--SDA SEMINARY, FAR EASTERN CIVISION 80-250 ADAMS,. W M--ELECTIVE MEMBER,-GEN CONE COMMITTEE 80-170. ADAMS, A M--RETIREMENT, APPRECIATION 80-100 ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEE INADCA/ - POLICY REVISION 60-313, ADONU, A N--TEACHER, SCA TEACHER TRG, GHANA, N EUROPE-V AFR CIV 80-256 ADV'ENTIST,BOOK CENTER SUBCOMMITTEE 80-331 ADVENTIST HEALTH SYSTEMS, LOMA LINDA--NEW CORPORATION 80-409 ADVENTIST JR YOUTH SOCIETY--CHURCH MANIAL REA, GC BUL 80-501, - ADVENTIST MEDIA CENTER ADVENTIST MEDIA' PRODUCTIONS--STUDY COMMITTEE' 80-147 GAMER', SKIP D--PHOTOGRAPHER. 80-411 . GARNED0', NEHEmIAS—QUALITY- OONTROLLER OFFICER 80-173 8IDWELL, D J--CONTROLLER ' ' 80-222 :BOARD AND:CORRORATE OFFICERS 80-318 BRASORD,, CURT/S—EVANGELIST,, VOICE OF PROPHECY' 80-424 CONSTITUENCY MEETING' -- ' 80-317 FiARDY,'GERALD—DIRECTOR, FIELD. SERVICES DEPT 80-227 cROOSIAD, A E—MANAGER/TREASVRER, IT IS WRITTEN 80-91' LIRE-OF CREDIT APPROVED . 80-237-, MATTHEwS, D S- DIRECTOR, FAITH FOR TODAY ' ' . 80-13 muSTOw„ DEREK--DIRECTOR, DEVEL E PUBLIC RELATIONS i80-2.Z4 SANCHEZ, REUBEN--BIBLE SCHOOL DIRECTOR, DIR OF PUBL REL CJ)Ev , 80-161 VANDULEK, PAUL--PLANT -

The Concept of Skin Bleaching and Body Image Politics in Kenya

“FAIR AND LOVELY”: THE CONCEPT OF SKIN BLEACHING AND BODY IMAGE POLITICS IN KENYA Joyce Khalibwa Okango A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2017 Committee: Jeffery A Brown, Advisor Jeremy Wallach Esther Clinton © 2017 Enter your First and Last Name All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown, Advisor The practice of skin bleaching or chemically lightening of skin has become a worldwide concern particularly in the past three decades. In Africa, these practices are increasingly becoming problematic due to the circumstances surrounding the procedure and the underlying health risks. Despite these threats, skin bleaching and other body augmentation procedures remain prevalent around the world. This thesis uses a multipronged approach in examining the concept of skin bleaching and body image politics in Kenya. I argue that colonial legacies, globalization, increase in the use of technology, and the digitization of Kenya television broadcasting has had a great impact on the spread and shift of cultures in Kenya resulting to such practices. I will also look at the role of a commercial spaces within a city in enabling and providing access to such practices to middle and lower class citizens. Additionally, this study aims at addressing the importance of decolonizing Kenyans concerning issues surrounding beauty and body image. iv This thesis is a special dedication to loving father, for believing in girl child education and sacrificing everything to see me succeed. For setting the bar so high for me and cheering me on as I made every stride. -

Third Culture Kids’: Migration Narratives on Belonging, Identity and Place

This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights and duplication or sale of all or part is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for research, private study, criticism/review or educational purposes. Electronic or print copies are for your own personal, non- commercial use and shall not be passed to any other individual. No quotation may be published without proper acknowledgement. For any other use, or to quote extensively from the work, permission must be obtained from the copyright holder/s. 1 ‘Third culture kids’: migration narratives on belonging, identity and place. Ms. Rachel May Cason Thesis submitted for consideration of Doctor of Philosophy degree status October 2015 Keele University 2 Contents: Abstract p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Chapter One: Introduction p. 5 Chapter Two: Mapping Third Culture Kids onto the Migration Landscape p. 19 Chapter Three: Experiences of Migration p. 47 Chapter Four: Multi-sited Methodologies p. 90 Chapter Five: The Third Culture Kid Experience – In the Field p. 123 Chapter Six: Third Culture Kids and a Sense of Belonging p. 156 Chapter Seven: Third Culture Kids and Identity p. 198 Chapter Eight: Third Culture Kids and Place p. 236 Chapter Nine: Cosmopolitanism, Identity and Experience p. 258 Chapter Ten: Conclusion – Migration narratives on belonging, identity and place p. 275 Bibliography p. 298 Appendices p. 326 3 Abstract Third Culture Kids are the children of people working outside their passport countries, and who are employed by international organisations as development experts, diplomats, missionaries, journalists, international NGO and humanitarian aid workers, or UN representatives. -

Knec Bulletin Mit I

JANUARY - JUNE YA NAT EN IO K N 2019 E A H L T E X IL A C M N IN OU ATIONS C IHAN KNEC BULLETIN MIT I THE KENYA NATIONAL EXAMINATIONS COUNCIL NEWS An Officer from KNEC Communication's Office, Maswai Johnpaul takes Amb (Dr) Amina Mohammed through KNEC Career Guidance Handbook during Skills and Career Event held at KICC Table of YA NAT EN IO K N E A H L T Monitoring Learners Progress........................... 4 KNEC sets record straight on Grade 3 E X IL A C MLP assessment............................................. 7 M N IN OU ATIONS C 2018 ndings on learners achievements........... 8 MITIHANI Parental Involvement................................ 16 KNEC showcases post school courses............. 18 THE KENYA NATIONAL DTE poor performances in maths and EXAMINATIONS COUNCIL science discussed............................................ 19 Group 4 subject assessment revised................ 20 NHC Building P.O. Box 73598 - 00200 Subject ofcers train on CBA............................ 21 City Square Nairobi, Kenya Customer care view......................................... 22 KNEC at KESSHA............................................. 23 Tel: +254 020 3341050/27 Fax: +254 020 2226032 KNEC at UoN open day..................................... 24 Email: [email protected] Bench marking tours........................................ 25 KNEC develops HIV/Aids policy........................ 27 Council Chairman Accessibility Audit............................................ 28 Dr. John Onsati, OGW Beyond Zero Marathon.................................... -

Writing for Kenya

Writing for Kenya Henry Muoria, London 1954. African Sources for African History Editorial Board Dmitri van den Bersselaar (University of Liverpool) Michel Doortmont (University of Groningen) Jan Jansen (University of Leiden) Advisory Board RALPH A. AUSTEN UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, USA WIM VAN BINSBERGEN AFRICA STUDIES CENTRE LEIDEN, NETHERLANDS KARIN BARBER AFRICA STUDIES CENTRE BIRMINGHAM, UK ANDREAS ECKERT UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG, GERMANY JOHN H. HANSON UNIVERSITY OF INDIANA, USA DAVID HENIGE UNIVERSITY OF MADISON, USA EISEI KURIMOTO OSAKA UNIVERSITY, JAPAN J. MATTHIEU SCHOFFELEERS UNIVERSITY OF LEIDEN, NETHERLANDS VOLUME 10 Writing for Kenya e Life and Works of Henry Muoria By Wangari Muoria-Sal, Bodil Folke Frederiksen, John Lonsdale and Derek Peterson LEIDEN • BOSTON 2009 Cover illustration: From the frontispiece of Henry Muoria’s rst pamphlet ‘Tungika atia iiya witu?’ or ‘What should we do, our people?’ (1945). For the text, see pp. 136-37. is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data Writing for Kenya : the life and works of Henry Muoria / by Wangari Muoria-Sal . [et al.]. p. cm. — (African sources for African history ; v. 10) Biographical material in English; texts of Muoria’s political pamphlets in Kikuyu with English translation. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17404-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Muoria, Henry. 2. Muoria, Henry—Family. 3. Journalists—Kenya—Biography. 4. Kenyans—England— London—Biography. 5. Kenyatta, Jomo. 6. Kikuyu (African people) 7. Kenya— Politics and government—To 1963. I. Muoria-Sal, Wangari. II. Muoria, Henry. III. Title. IV. Series. PN5499.K42M868 2009 070.92—dc22 [B] 2009010954 ISSN 1567-6951 ISBN 978 90 04 17404 7 Copyright 2009 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, e Netherlands. -

2013 Acropolis

Whittier College Wardman Library Poet Commons Acropolis (Yearbook) Archives and Special Collections 2013 2013 Acropolis Whittier College Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/acropolis lITTlER COLLEGE EST. 1887 I, iiàieMaiy, bc4J, )/%i1ie /0/ 'Mle &t ote'nL4 Welcome 2 13406 East Philadelphia St. Student Life 10 Whittier, CA 90602 Academics 28 562.298.0919 Societies 44 Organizations 70 Check out the new website! Sports 78 www.whittier.edu Seniors 122 Student population: 1643 Colophon 144 I '*, It is with my great pleasure in providing you with the 2012-2013 Acropolis Yearbook, a yearly produced media that documents the history of this Quaker campus. This year's book has been dedicated to the 125th Anniversary of Whittier College and the 100th Anniversary of the Rock. Much has happened this school year, and we have done our best in providing a look back at 6 everything in celebration of this mark in our history. Editor-in-Chief As you will see running along the bottom of every page of this year's book is a historic timeline. We have spent all year gathering facts and pictures to show the history of our entirety here in Whittier. From our start as a city, our founders, the creation of Whittier Academy, to the beginning die c4q of Whittier College, all the way until now. Our hope is that you will find it informing and gain a sense of pride for being a part of the Poet family and legacy. Our college holds a lot of value, and sometimes, it needs to be recognized more often than not. -

Cathrin Skog En Av Favoriterna I Miss World 2006

2006-09-18 11:21 CEST Cathrin Skog en av favoriterna i Miss World 2006 Cathrin Skog, 19 årig call-center agent från den lilla byn Nälden i närheten av Östersund är Sveriges hopp i årets Miss World 2006. Cathrins ambition i framtiden är att studera internationell ekonomi och hon älskar att måla och lyssna på musik, speciellt street, disco och funk. Hennes personliga motto i livet är att alltid se livet från den ljusa sidan och att aldrig ge upp. Finalen i Miss World 2006 kommer att hållas på lördagen den 30 september i Polen där den 56: e Miss World vinnaren kommer att koras av både en expertjury på plats och via internetröster från hela världen. Cathrin är en av förhandsfavoriterna och spelas just nu till 17 gånger pengarna. Miss Australien (Sabrina Houssami) och Miss Venezuela (Alexandra Federica Guzaman Diamante) delar på favoritskapet med spel till 8 gånger pengarna. För mer info om tävlingen, se www.missworld.com Odds Vinnarspel Miss World 2006 Miss Australia 8.00 Miss Venezuela 8.00 Miss Canada 11.00 Miss India 11.00 Miss Lebanon 13.00 Miss Angola 17.00 Miss Columbia 17.00 Miss Dominican Republic 17.00 Miss South Africa 17.00 Miss Sweden 17.00 Miss Mexico 19.00 Miss Philippines 19.00 Miss Puerto Rica 19.00 Miss Czech Republic 21.00 Miss Jamaica 21.00 Miss Martinique 21.00 Miss Spain 21.00 Miss Iceland 23.00 Miss Italy 26.00 Miss Panama 26.00 Miss Singapore 29.00 Miss Ukraine 29.00 Miss Brazil 34.00 Miss Chile 34.00 Miss China 34.00 Miss Greece 34.00 Miss Nigeria 34.00 Miss Peru 34.00 Miss Poland 34.00 Miss Turkey 34.00 Miss USA 34.00 -

The To-Do List in 2005, We Joined a Biker Couple on Their Epic

SEX ADVENTURE The To-Do List Two Ride the World: Part II MOROCCO W. SAHARA MAURITANIA In 2005, we joined a biker couple on their epic journey SENEGAL across Europe. Now, in Part II, we taste the true grit of Africa on the back of their GAMBIA MALI BMWs. Want to ride? Take your directions from GHANA this tip sheet UGANDA SAO TOME KENYA ZANZIBAR TANZANIA TRANS DANCE BY SIMON THOMAS PHOTOGRAPHS SIMON AND LISA THOMAS MALAWI ZAMBIA MOZAMBIQUE BOTSWANA NAMIBIA C R E D I T SOUTH AFRICA PHOTOGRAPH 168 MEN’S HEALTH MARCH 2007 MARCH 2007 MEN’S HEALTH 169 ADVENTURE Two Ride the World: Part II MOROCCO MALI THE ROUTE We arrive in Africa at Fes, Morocco, with Cape THE ROUTE “That’s a bloody river,” yells Lisa. Her con- Town, South Africa our southern destination on this vast con- cern is justified. The GPS and map list our watery obstacle tinent. It’s quite intimidating studying the map and taking as a stream. Our only option is to put both our heavy bikes into in the length of this massive chunk of land. Drive across Africa a small wooden dug-out to cross into Mali. “Well, the bikes are on a motorbike? Now there’s a challenge. Fortunately, our land- SENEGAL going to drown and our journey comes to a crocodile infested GHANA ing in Morocco takes us straight to the main course – the THE ROUTE Taking advantage of a little known piste, we end... or we make it, and have a great story.” Luckily the latter THE ROUTE By the time we slide, drop and skid our way to bustling old medina of Fes. -

SS6 August 2008

About Talented Cameroonians at Home and Abroad N° 013 Miss South Africa USA Miss Kenya USA Miss Liberia USA Miss Sierra Leone USA Miss Cameroon USA Miss Gambia USA Miss Guinea USA Nyasha Zimucha Victoria Njau Belloh Julius Philippa Lahai-Swaray Danielle Mingana Fochive Tanta Badjan Binta Diao Miami Florida Texas Georgia Georgia Maryland New York New Jersey Miss Zimbabwe USA Miss Ghana USA Miss Burundi USA Miss Nigeria USA Miss South Sudan USA Miss Ethiopia USA Miss Senegal USA Busi Mlambo Krystle Simpson Danielle Ntahonkiney Esosa Edosomwan Nathalie Zambakari Aziza Elteib Mariama Brown Texas Maryland Texas New York Georgia Georgia Miss Democratic Re- Miss Uganda USA Miss Zambia USA public of Congo Imat Akelo-Opio Mutinta Suuya Andrea Mvemba International Georgia ello Readers, Your favourite E-Magazine is one year old. We acknowledge that your interest and comments have been invaluable to our editorial work and so we hereby pledge our commitment to continue this initiative that ushers in a new era of hardwork, creativity and results that will accompany our country on the difficult path towards development. Things will never be the same again. H HEALTH FOR ALL has been a bestselling slogan and dream for so many decades in Cameroon like in other countries. While we all see Health For All as an achievement that permits everyone to get care in order to prevent or treat most common ailments at affordable prices, we still observe that despite all the individual, collective and government efforts aimed at improving on healthcare delivery systems , so many obstacles imposed by more communicable and non-communicable diseases still exist in an environment marked by poverty.