Lecture Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Functions of a Single Variable a Detailed Development

ANALYSIS OF FUNCTIONS OF A SINGLE VARIABLE A DETAILED DEVELOPMENT LAWRENCE W. BAGGETT University of Colorado OCTOBER 29, 2006 2 For Christy My Light i PREFACE I have written this book primarily for serious and talented mathematics scholars , seniors or first-year graduate students, who by the time they finish their schooling should have had the opportunity to study in some detail the great discoveries of our subject. What did we know and how and when did we know it? I hope this book is useful toward that goal, especially when it comes to the great achievements of that part of mathematics known as analysis. I have tried to write a complete and thorough account of the elementary theories of functions of a single real variable and functions of a single complex variable. Separating these two subjects does not at all jive with their development historically, and to me it seems unnecessary and potentially confusing to do so. On the other hand, functions of several variables seems to me to be a very different kettle of fish, so I have decided to limit this book by concentrating on one variable at a time. Everyone is taught (told) in school that the area of a circle is given by the formula A = πr2: We are also told that the product of two negatives is a positive, that you cant trisect an angle, and that the square root of 2 is irrational. Students of natural sciences learn that eiπ = 1 and that sin2 + cos2 = 1: More sophisticated students are taught the Fundamental− Theorem of calculus and the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra. -

Variables in Mathematics Education

Variables in Mathematics Education Susanna S. Epp DePaul University, Department of Mathematical Sciences, Chicago, IL 60614, USA http://www.springer.com/lncs Abstract. This paper suggests that consistently referring to variables as placeholders is an effective countermeasure for addressing a number of the difficulties students’ encounter in learning mathematics. The sug- gestion is supported by examples discussing ways in which variables are used to express unknown quantities, define functions and express other universal statements, and serve as generic elements in mathematical dis- course. In addition, making greater use of the term “dummy variable” and phrasing statements both with and without variables may help stu- dents avoid mistakes that result from misinterpreting the scope of a bound variable. Keywords: variable, bound variable, mathematics education, placeholder. 1 Introduction Variables are of critical importance in mathematics. For instance, Felix Klein wrote in 1908 that “one may well declare that real mathematics begins with operations with letters,”[3] and Alfred Tarski wrote in 1941 that “the invention of variables constitutes a turning point in the history of mathematics.”[5] In 1911, A. N. Whitehead expressly linked the concepts of variables and quantification to their expressions in informal English when he wrote: “The ideas of ‘any’ and ‘some’ are introduced to algebra by the use of letters. it was not till within the last few years that it has been realized how fundamental any and some are to the very nature of mathematics.”[6] There is a question, however, about how to describe the use of variables in mathematics instruction and even what word to use for them. -

A Quick Algebra Review

A Quick Algebra Review 1. Simplifying Expressions 2. Solving Equations 3. Problem Solving 4. Inequalities 5. Absolute Values 6. Linear Equations 7. Systems of Equations 8. Laws of Exponents 9. Quadratics 10. Rationals 11. Radicals Simplifying Expressions An expression is a mathematical “phrase.” Expressions contain numbers and variables, but not an equal sign. An equation has an “equal” sign. For example: Expression: Equation: 5 + 3 5 + 3 = 8 x + 3 x + 3 = 8 (x + 4)(x – 2) (x + 4)(x – 2) = 10 x² + 5x + 6 x² + 5x + 6 = 0 x – 8 x – 8 > 3 When we simplify an expression, we work until there are as few terms as possible. This process makes the expression easier to use, (that’s why it’s called “simplify”). The first thing we want to do when simplifying an expression is to combine like terms. For example: There are many terms to look at! Let’s start with x². There Simplify: are no other terms with x² in them, so we move on. 10x x² + 10x – 6 – 5x + 4 and 5x are like terms, so we add their coefficients = x² + 5x – 6 + 4 together. 10 + (-5) = 5, so we write 5x. -6 and 4 are also = x² + 5x – 2 like terms, so we can combine them to get -2. Isn’t the simplified expression much nicer? Now you try: x² + 5x + 3x² + x³ - 5 + 3 [You should get x³ + 4x² + 5x – 2] Order of Operations PEMDAS – Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally, remember that from Algebra class? It tells the order in which we can complete operations when solving an equation. -

Leibniz and the Infinite

Quaderns d’Història de l’Enginyeria volum xvi 2018 LEIBNIZ AND THE INFINITE Eberhard Knobloch [email protected] 1.-Introduction. On the 5th (15th) of September, 1695 Leibniz wrote to Vincentius Placcius: “But I have so many new insights in mathematics, so many thoughts in phi- losophy, so many other literary observations that I am often irresolutely at a loss which as I wish should not perish1”. Leibniz’s extraordinary creativity especially concerned his handling of the infinite in mathematics. He was not always consistent in this respect. This paper will try to shed new light on some difficulties of this subject mainly analysing his treatise On the arithmetical quadrature of the circle, the ellipse, and the hyperbola elaborated at the end of his Parisian sojourn. 2.- Infinitely small and infinite quantities. In the Parisian treatise Leibniz introduces the notion of infinitely small rather late. First of all he uses descriptions like: ad differentiam assignata quavis minorem sibi appropinquare (to approach each other up to a difference that is smaller than any assigned difference)2, differat quantitate minore quavis data (it differs by a quantity that is smaller than any given quantity)3, differentia data quantitate minor reddi potest (the difference can be made smaller than a 1 “Habeo vero tam multa nova in Mathematicis, tot cogitationes in Philosophicis, tot alias litterarias observationes, quas vellem non perire, ut saepe inter agenda anceps haeream.” (LEIBNIZ, since 1923: II, 3, 80). 2 LEIBNIZ (2016), 18. 3 Ibid., 20. 11 Eberhard Knobloch volum xvi 2018 given quantity)4. Such a difference or such a quantity necessarily is a variable quantity. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) • His father, a professor of Philosophy, died when he was small, and he was brought up by his mother. • He learnt Latin at school in Leipzig, but taught himself much more and also taught himself some Greek, possibly because he wanted to read his father’s books. • He studied law and logic at Leipzig University from the age of fourteen – which was not exceptionally young for that time. • His Ph D thesis “De Arte Combinatoria” was completed in 1666 at the University of Altdorf. He was offered a chair there but turned it down. • He then met, and worked for, Baron von Boineburg (at one stage prime minister in the government of Mainz), as a secretary, librarian and lawyer – and was also a personal friend. • Over the years he earned his living mainly as a lawyer and diplomat, working at different times for the states of Mainz, Hanover and Brandenburg. • But he is famous as a mathematician and philosopher. • By his own account, his interest in mathematics developed quite late. • An early interest was mechanics. – He was interested in the works of Huygens and Wren on collisions. – He published Hypothesis Physica Nova in 1671. The hypothesis was that motion depends on the action of a spirit ( a hypothesis shared by Kepler– but not Newton). – At this stage he was already communicating with scientists in London and in Paris. (Over his life he had around 600 scientific correspondents, all over the world.) – He met Huygens in Paris in 1672, while on a political mission, and started working with him. -

Mathematical Analysis, Second Edition

PREFACE A glance at the table of contents will reveal that this textbooktreats topics in analysis at the "Advanced Calculus" level. The aim has beento provide a develop- ment of the subject which is honest, rigorous, up to date, and, at thesame time, not too pedantic.The book provides a transition from elementary calculusto advanced courses in real and complex function theory, and it introducesthe reader to some of the abstract thinking that pervades modern analysis. The second edition differs from the first inmany respects. Point set topology is developed in the setting of general metricspaces as well as in Euclidean n-space, and two new chapters have been addedon Lebesgue integration. The material on line integrals, vector analysis, and surface integrals has beendeleted. The order of some chapters has been rearranged, many sections have been completely rewritten, and several new exercises have been added. The development of Lebesgue integration follows the Riesz-Nagyapproach which focuses directly on functions and their integrals and doesnot depend on measure theory.The treatment here is simplified, spread out, and somewhat rearranged for presentation at the undergraduate level. The first edition has been used in mathematicscourses at a variety of levels, from first-year undergraduate to first-year graduate, bothas a text and as supple- mentary reference.The second edition preserves this flexibility.For example, Chapters 1 through 5, 12, and 13 providea course in differential calculus of func- tions of one or more variables. Chapters 6 through 11, 14, and15 provide a course in integration theory. Many other combinationsare possible; individual instructors can choose topics to suit their needs by consulting the diagram on the nextpage, which displays the logical interdependence of the chapters. -

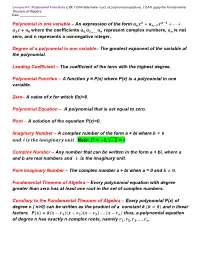

Lesson 4-1 Polynomials

Lesson 4-1: Polynomial Functions L.O: I CAN determine roots of polynomial equations. I CAN apply the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra. Date: ________________ 풏 풏−ퟏ Polynomial in one variable – An expression of the form 풂풏풙 + 풂풏−ퟏ풙 + ⋯ + 풂ퟏ풙 + 풂ퟎ where the coefficients 풂ퟎ,풂ퟏ,…… 풂풏 represent complex numbers, 풂풏 is not zero, and n represents a nonnegative integer. Degree of a polynomial in one variable– The greatest exponent of the variable of the polynomial. Leading Coefficient – The coefficient of the term with the highest degree. Polynomial Function – A function y = P(x) where P(x) is a polynomial in one variable. Zero– A value of x for which f(x)=0. Polynomial Equation – A polynomial that is set equal to zero. Root – A solution of the equation P(x)=0. Imaginary Number – A complex number of the form a + bi where 풃 ≠ ퟎ 풂풏풅 풊 풊풔 풕풉풆 풊풎풂품풊풏풂풓풚 풖풏풊풕 . Note: 풊ퟐ = −ퟏ, √−ퟏ = 풊 Complex Number – Any number that can be written in the form a + bi, where a and b are real numbers and 풊 is the imaginary unit. Pure imaginary Number – The complex number a + bi when a = 0 and 풃 ≠ ퟎ. Fundamental Theorem of Algebra – Every polynomial equation with degree greater than zero has at least one root in the set of complex numbers. Corollary to the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra – Every polynomial P(x) of degree n ( n>0) can be written as the product of a constant k (풌 ≠ ퟎ) and n linear factors. 푷(풙) = 풌(풙 − 풓ퟏ)(풙 − 풓ퟐ)(풙 − 풓ퟑ) … . -

Variables: Syntax, Semantics, and Situations

VARIABLES: SYNTAX, SEMANTICS AND SITUATIONS JOHN T. BALDWIN ABSTRACT. We expand the usual mathematical treatment of the syntax and semantics of variable to include consideration of the assignment of concrete referents in order to apply the mathematics to a real world situation. We lay out this framework in the context of high school algebra and discuss its use in analyzing teaching and learning. Keywords: equation,function, School algebra, Tarski semantics, syntax, variables Developing the concept of variable seems to be a major obstacle for students in learning algebra [KN04, MC01, LM99, Usi88]. In this article we describe in the context of high school algebra a framework for understanding the notion of variable. Two components of this framework, syntax and semantics, are standard mathematical notions. Since their precise formulation might not be familiar to the reader, we summarize the ideas in the high school algebra context and place them in a historical framework. But this analysis suffices only for ‘naked math’. We then discuss the third component: situation. If we view these three notions as the vertices of a triangle, our claim is that all three vertices of the triangle are essential elements of learning algebra. The goal of this paper is to lay out this mathematical and epistemological framework; in future work we intend to employ this analysis as a tool to explore specific lessons and student work. This paper expands one section of our joint work with Hyung Sook Lee and Alexander Ra- dosavljevic [BLR00]. We acknowledge helpful comments by Sergei Abramovich, Daniel Chazan, William Howard, Cathy Kessel, Lena Khisty, Dan Miltner, Mara Martinez, Aria Razfar, Kelly Rivette, Judah Schwartz and Kristin Umland. -

18.01 Single Variable Calculus Fall 2006

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 18.01 Single Variable Calculus Fall 2006 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. Lecture 9 18.01 Fall 2006 Lecture 9: Linear and Quadratic Approximations Unit 2: Applications of Differentiation Today, we’ll be using differentiation to make approximations. Linear Approximation y y = b+a(x-x0) b = f(x0) ; a = f’(x0 ) y=f(x) (x0 ,f(x0 )) x Figure 1: Tangent as a linear approximation to a curve The tangent line approximates f(x). It gives a good approximation near the tangent point x0. As you move away from x0, however, the approximation grows less accurate. 0 f(x) ≈ f(x0) + f (x0)(x − x0) Example 1. f(x) = ln x; x0 = 1 (basepoint) 1 � f(1) = ln 1 = 0; f 0(1) = � = 1 � x �x=1 0 ln x ≈ f(1) + f (1)(x − 1) = 0 + 1 · (x − 1) = x − 1 Change the basepoint: x = 1 + u =) u = x − 1 ln(1 + u) ≈ u Basepoint u0 = x0 − 1 = 0. 1 Lecture 9 18.01 Fall 2006 Basic list of linear approximations In this list, we always use base point x0 = 0 and assume that jxj << 1. 1. sin x ≈ x (if x ≈ 0) (see part a of Fig. 2) 2. cos x ≈ 1 (if x ≈ 0) (see part b of Fig. 2) x 3. e ≈ 1 + x (if x ≈ 0) 4. ln(1 + x) ≈ x (if x ≈ 0) r 5. (1 + x) ≈ 1 + rx (if x ≈ 0) Proofs 0 Proof of 1: Take f(x) = sin x, then f (x) = cos x and f(0) = 0 0 0 f (0) = 1; f(x) ≈ f(0) + f (0)(x − 0) = 0 + 1:x So using basepoint x0 = 0; f(x) = x. -

Matrices and Linear Algebra

Chapter 2 Matrices and Linear Algebra 2.1 Basics Definition 2.1.1. A matrix is an m n array of scalars from a given field F . The individual values in the matrix× are called entries. Examples. 213 12 A = B = 124 34 − The size of the array is–written as m n,where × m n × number of rows number of columns Notation a11 a12 ... a1n a21 a22 ... a2n rows ←− A = a a ... a n1 n2 mn columns A := uppercase denotes a matrix a := lower case denotes an entry of a matrix a F. ∈ Special matrices 33 34 CHAPTER 2. MATRICES AND LINEAR ALGEBRA (1) If m = n, the matrix is called square.Inthiscasewehave (1a) A matrix A is said to be diagonal if aij =0 i = j. (1b) A diagonal matrix A may be denoted by diag(d1,d2,... ,dn) where aii = di aij =0 j = i. The diagonal matrix diag(1, 1,... ,1) is called the identity matrix and is usually denoted by 10... 0 01 In = . . .. 01 or simply I,whenn is assumed to be known. 0 = diag(0,... ,0) is called the zero matrix. (1c) A square matrix L is said to be lower triangular if ij =0 i<j. (1d) A square matrix U is said to be upper triangular if uij =0 i>j. (1e) A square matrix A is called symmetric if aij = aji. (1f) A square matrix A is called Hermitian if aij =¯aji (¯z := complex conjugate of z). (1g) Eij has a 1 in the (i, j) position and zeros in all other positions. -

Glossary from Math Analysis

A Glossary for Pre-calculus These terms were identified during the Cal-PASS deconstruction of the California State Standards for Math Analysis, Linear Algebra, and Trigonometry By the Cal-PASS Central San Diego Math Professional Learning Council Bruce Arnold, Brenda Kracht, Judy Ross, Terrie Teegarden and Maurice Tompkins 1 Preface: In the deconstruction of the California state standards for trigonometry, linear algebra and mathematical analysis for the Cal-PASS Content Standards Deconstruction projects, it became apparent that terms were used for which no definition was given. The San Diego Central Cal-PASS Math Professional Learning Council felt that many of these terms might be unfamiliar to a precalculus instructor. Hence, a list of key terms and their appropriate definitions were developed, resulting in this document. These descriptions are intended to be explanatory rather than to provide precise mathematical rigor. Some terms, such as logarithms, are not included even though they are essential for calculus preparation because they do not appear in the precalculus standards. Many high schools combine some of the standards from trigonometry, linear algebra, and mathematical analysis to form a pre-calculus course. Pre-calculus courses in community colleges and four year institutions also combine the content of these standards. This integrated approach reflects the fact that these topics do not exist in isolation, but rather work in unity with each other. It is also important to note that the order of the standards, or even groups of standards, may not reflect the order in which they might appear in standard textbooks or course outlines. Suggested topic sequence for a pre-calculus course: Mathematical Analysis 4 and 6 Note that there are many topics loosely associated with 4 that are not mentioned, such as the Rational Root Theorem, Descartes’ Rule of signs, etc.