Names in Multi-Lingual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Uniform Was the Old Norse Religion?

II. Old Norse Myth and Society HOW UNIFORM WAS THE OLD NORSE RELIGION? Stefan Brink ne often gets the impression from handbooks on Old Norse culture and religion that the pagan religion that was supposed to have been in Oexistence all over pre-Christian Scandinavia and Iceland was rather homogeneous. Due to the lack of written sources, it becomes difficult to say whether the ‘religion’ — or rather mythology, eschatology, and cult practice, which medieval sources refer to as forn siðr (‘ancient custom’) — changed over time. For obvious reasons, it is very difficult to identify a ‘pure’ Old Norse religion, uncorroded by Christianity since Scandinavia did not exist in a cultural vacuum.1 What we read in the handbooks is based almost entirely on Snorri Sturluson’s representation and interpretation in his Edda of the pre-Christian religion of Iceland, together with the ambiguous mythical and eschatological world we find represented in the Poetic Edda and in the filtered form Saxo Grammaticus presents in his Gesta Danorum. This stance is more or less presented without reflection in early scholarship, but the bias of the foundation is more readily acknowledged in more recent works.2 In the textual sources we find a considerable pantheon of gods and goddesses — Þórr, Óðinn, Freyr, Baldr, Loki, Njo3rðr, Týr, Heimdallr, Ullr, Bragi, Freyja, Frigg, Gefjon, Iðunn, et cetera — and euhemerized stories of how the gods acted and were characterized as individuals and as a collective. Since the sources are Old Icelandic (Saxo’s work appears to have been built on the same sources) one might assume that this religious world was purely Old 1 See the discussion in Gro Steinsland, Norrøn religion: Myter, riter, samfunn (Oslo: Pax, 2005). -

The Nobility and the Manors

South Sweden, it is possible to discuss the reasons why noble families Gradually abandoned their manors from the early-eiGhteenth century on- wards. The Nobility and the Manors Since the Middle AGes, the Swedish population was divided into four es- tates, all of which were represented in the parliament: the nobility, the clerGy, the burghers and the freehold farmers. From the Middle AGes and onwards, freehold farmers owned at least O0% of the land, which increased in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to around Q0%. / The nobility of Sweden has its origins in an act of -ST0, in which the Swedish king formal- ized a pre-existing relationship between the king, the landowning lords and the freehold farmers. Tax exemptions and the right to found tax-exempt manors or noble ‘seats’ ( sätesgårdar ) were promised to those who could pay for horses and armoured men-at-arms to serve in the cavalry. Q When Swe- den became a nation state in the sixteenth century, noble families began to serve as officers and civil servants in a more complex and better organized administration which had higher expectations for skills and education. In order to establish a more continental style of nobility, necessary for the expanding kinGdom, which desired to become a great power equal to those on the continent, two new titles were introduced in the -/Q0s: count ( greve ) and baron ( friherre ). The nobility was then divided into two; the titled no- bility (högadel ) consisting of counts and barons, and the untitled nobility (lågadel ). From this point noble status also became hereditary, meaning that all sons and daughters inherited their fathers’ titles. -

Meyer's Accent Contours Revisited

TMH-QPSR Vol. 44 – Fonetik 2002 Meyer’s accent contours revisited Olle Engstrand1 and Gunnar Nyström2 1Department of Linguistics, Stockholm University 2Institute for Dialectology, Onomastics and Folklore Research (SOFI), Uppsala Abstract Do E.A. Meyer’s tonal word accents contours from the Swedish dialects provide a reliable basis for quantitative analysis? Measurements made on acute and grave tone-peaks in a number of dialects spoken in the province of Dalarna suggested that the timing of grave tonal peaks tended to vary systematically from south-east to north-west. The former dialects had relatively late and the latter relatively early tone-peaks. This finding suggests that Meyer’s accent data may be sufficiently accurate to reflect systematic variation within broad dialect areas. Implications for the historical development of the Dalarna dialects are discussed. Introduction Several decades ago, E.A. Meyer compiled his pioneering survey of tonal word accent contours in 100 Swedish dialects (Meyer 1937, 1954). Pitch curves were automatically generated using a pitch meter that Meyer himself had invented. The original pitch curves are thus likely to be quite accurate. To enhance the dialect-specific tonal characteristics, the original contours were time-normalized, averaged and smoothed by Figure 1. Tonal contours representing the eye. These schematized contours were arranged Central Swedish dialects (Stockholm, upper by province and displayed on charts. panel) and the Dalarna dialects (Leksand, lower The Meyer contours have proved useful in panel). establishing accent-based dialect typologies In this paper, the question is raised whether the (Gårding 1977, Bruce & Gårding 1978, Öhman Gårding and Bruce scheme can be elaborated to 1967). -

Kingdom of Sweden

Johan Maltesson A Visitor´s Factbook on the KINGDOM OF SWEDEN © Johan Maltesson Johan Maltesson A Visitor’s Factbook to the Kingdom of Sweden Helsingborg, Sweden 2017 Preface This little publication is a condensed facts guide to Sweden, foremost intended for visitors to Sweden, as well as for persons who are merely interested in learning more about this fascinating, multifacetted and sadly all too unknown country. This book’s main focus is thus on things that might interest a visitor. Included are: Basic facts about Sweden Society and politics Culture, sports and religion Languages Science and education Media Transportation Nature and geography, including an extensive taxonomic list of Swedish terrestrial vertebrate animals An overview of Sweden’s history Lists of Swedish monarchs, prime ministers and persons of interest The most common Swedish given names and surnames A small dictionary of common words and phrases, including a small pronounciation guide Brief individual overviews of all of the 21 administrative counties of Sweden … and more... Wishing You a pleasant journey! Some notes... National and county population numbers are as of December 31 2016. Political parties and government are as of April 2017. New elections are to be held in September 2018. City population number are as of December 31 2015, and denotes contiguous urban areas – without regard to administra- tive division. Sports teams listed are those participating in the highest league of their respective sport – for soccer as of the 2017 season and for ice hockey and handball as of the 2016-2017 season. The ”most common names” listed are as of December 31 2016. -

Population Genetic Structure of Crucian Carp (Carassius Carassius) in Man-Made Ponds and Wild Populations in Sweden

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Aquacult Int (2015) 23:359–368 DOI 10.1007/s10499-014-9820-4 Population genetic structure of crucian carp (Carassius carassius) in man-made ponds and wild populations in Sweden S. Janson • J. Wouters • M. Bonow • I. Svanberg • K. H. Olse´n Received: 17 January 2014 / Accepted: 11 August 2014 / Published online: 21 August 2014 Ó The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Although once popular prior to the last century, the aquaculture of crucian carp Carassius carassius (L. 1758) in Sweden gradually fell from favour. This is the first genetic comparison of crucian carp from historic man-made ponds in the Scandinavian Peninsula. The aim was to identify old populations without admixture and to compare the relationship of pond populations from different provinces in Sweden. In total, nine microsatellite loci from 234 individuals from 20 locations in varied parts of Sweden were analysed. The genetic distances of crucian carp populations indicated that the populations in the southernmost province of Sweden, Scania, shared a common history. A pond population in the province Sma˚land also showed a common inheritance with this group. In the province Uppland, further north in Sweden, the population genetic distances suggested a much more complex history of crucian carp distributions in the ponds. The data showed that there are some ponds with potentially old populations without admixture, but also that several ponds might have been stocked with fish from many sources. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153 -

Morphological Variation and ITS Phylogeny of Chaenotheca Trichialis and C

Ann. Bot. Fennici 39: 73–80 ISSN 0003-455X Helsinki 8 March 2002 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2002 Morphological variation and ITS phylogeny of Chaenotheca trichialis and C. xyloxena (Coniocybaceae, lichenized ascomycetes) Leif Tibell Department of Systematic Botany, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18D, SE-752 36 Uppsala, Sweden Received 1 June 2001, accepted 19 October 2001 Tibell, L. 2002: Morphological variation and ITS phylogeny of Chaenotheca trichialis and C. xyloxena (Coniocybaceae, lichenized ascomycetes). — Ann. Bot. Fennici 39: 73–80. Chaenotheca trichialis and C. xyloxena have been characterized by differences in their morphology, anatomy and ecology. They are, however, often difficult to distinguish. In a molecular phylogeny based on ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA sequences the specimens of C. xyloxena but not those of C. trichialis formed a monophyletic group. To some extent the analysis also revealed regional groupings. Key words: Ascomycotina, classification, Coniocybaceae, Chaenotheca, ITS, phylog- eny, rDNA Introduction wood, have during the second half of the twenti- eth century been accepted as probably closely Several Chaenotheca species have wide distri- related but morphologically distinct species. butions, occur in a variety of niches, and are Chaenotheca trichialis was described by Achar- morphologically very plastic. Since the ecophe- ius already in 1808, and C. xyloxena was de- notypic variation is considerable and not easily scribed by Nádvorník in 1934. They were ac- understood, it is often difficult to identify speci- cepted as distinct species by, for example, To- mens, and species delimitation is often problem- bolewski (1966), Tibell (1980, 1987, 1999), atic. In some habitats, the species are very easily Puntillo (1994), Goward (1999), and Selva and recognised, but in others different species seem Tibell (1999). -

Annual Report 2019 RS 2019–0242

Annual Report 2019 RS 2019–0242 2 Annual Report 2019 Chapter name Content Region Stockholm’s surplus gives us the Companies ......................................................................... 70 power to face the pandemic ............................................ 4 Landstingshuset i Stockholm AB ......................................71 Södersjukhuset AB ............................................................71 Statement by the Regional Chief Executive .................. 6 Danderyds Sjukhus AB ......................................................73 Summary of operational development ......................... 8 Södertälje Sjukhus AB .......................................................75 The Regional Group...........................................................12 S:t Eriks Ögonsjukhus AB .................................................76 Folktandvården Stockholms län AB ................................. 78 Important conditions for profit/loss and Ambulanssjukvården i Storstockholm AB ........................79 financial position...............................................................14 Stockholm Care AB ..........................................................80 Important events ...............................................................16 MediCarrier AB ................................................................80 Locum AB ..........................................................................81 Steering and follow-up of the regional AB Stockholms Läns Landstings Internfinans ................. 82 -

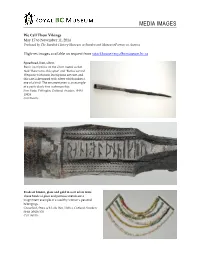

Media-Images-We-Call-Them-Vikings

MEDIA IMAGES We Call Them Vikings May 17 to November 11, 2014 Produced by The Swedish History Museum in Sweden and MuseumsPartner in Austria High-res images available on request from [email protected] Spearhead, Iron, silver. Runic inscriptions on the silver coated socket read ‘Rane owns this spear’ and ‘Botfus carved’. Weapons with runic inscriptions are rare, and this one is decorated with silver which makes it one of a kind. The ornamentation is an example of a particularly fine craftsmanship. Stor-Vede, Follingbo, Gotland, Sweden. SHM 15928 (FID 914435) Beads of bronze, glass and gold in a set of six rows. These beads of glass and precious metals are a magnificent example of a wealthy woman’s personal belongings. Gravefind, Stora och Lilla Ihre, Hellvi, Gotland, Sweden. SHM 20826:370 (FID 108059) Pendant, Thorshammer, silver with filigree ornamentation. This pendant has the shape of a Thor’s hammer, an object that could have been used in connection to burials and to cult activities. It is the only one of its kind and is finely crafted. Location of find is not known, Scania, Sweden. SHM 9822 (FID 106659) Key. Bronze. On the handle is a Christian motif, showing the crucifixion, above a small palmette. Keys are common in Viking Age Scandinavian material, but it is very rare indeed to have them adorned with such obvious Christian symbolism. Sweden. SHM 6819:535 (FID 364197) Pendant, silver and gilded. This figurine may represent Frigg, the most powerful of the Asynjurs or female gods. The details in the clothing give many clues to the way the clothes were used. -

On Some Factors Affecting the Chemical Composition of Swedish Fresh Waters

Geochimlca et Cosmochlmlca Acta, 1955, Vol. 7, pp. 129 to 150. Pergamon Press Ltd. London On some factors affecting the chemical composition of Swedish fresh waters EvrLLE GoRHAM The Botany Department, University College, London* (Received December 1954) ABSTRACT An att{lmpt is made to relate variations in the chemical composition of Swedish fresh waters (mainly analyzed by LOHAMMAR, 1938) to topographical, geochemical, and biological factors. The following are among the more general conclusions: (l) In Uppland lake waters, and certain of those in Dalarna, total salt concentration is clearly related to altitude. (2) There are distinct differences in ionic proportions between richer and poorer lake waters in both Dalarna and Uppland. In Dalarna the preponderance of moraine or Daliilven river sediments appears to be the important factor. In Uppland the high proportions of Cl, Na, and Mg in the waters of the lowest and richest lakes bear witness to the marine submergence of the district at the end of the glacial period. (3) A comparison of Dalarna drainage and seepage lakes reveals that the waters of the latter are proportionally very rich in K but low in Ca. It is suggested that this may be due to a lesser degree of biotic influence on the waters reaching the seepage lakes. (4) Dalarna seepage lakes exhibit low S04 levels in their waters, which may be connected with a slow rate of water transfer through them. (5) The cations of bog waters are dominated by Na, thoS{l of fen waters by Ca. This illustrates the :relative importance of atmospheric precipitation in the former, and mineral soil leaching in the latter. -

Plants & Ecology

Population structure and distribution of the declining endangered forest plant Chimaphila umbellata by Anna Lundell Plants & Ecology The Department of Ecology, 2014/1 Environment and Plant Sciences Stockholm University Population structure and distribution of the declining endangared forest plant Chimaphila umbellata by Anna Lundell Supervisors: Ove Eriksson & Sara Cousins Plants & Ecology The Department of Ecology, 2014/1 Environment and Plant Sciences Stockholm University Plants & Ecology The Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences Stockholm University S-106 91 Stockholm Sweden © The Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences ISSN 1651-9248 Printed by FMV Printcenter Cover: Flowering Chimaphila umbellata. Photo by Margareta Edqvist. Summary The occurrence of the rare forest plant Chimaphila umbellata has decreased with approximately 80 % in Uppland and its decline is also reported for other regions in Sweden. Suggested causes of decline include the increasingly shaded conditions in understory habitats and increased competition from Vaccinium myrtillus and graminoid species. The aim of the study was to investigate the effects of various biotic and abiotic conditions on C. umbellata populations with regard to population size, flowering frequency, fruit set and seed production. Conditions analyzed include light inflow, coverage of competitive species, soil nitrogen, continuity of forest cover and soil texture, which were investigated in 38 C. umbellata sites in Uppland and Södermanland, Sweden. Results showed that population size was negatively affected by the coverage of competitive species. Population size was not affected by light availability, but increased shading resulted in a decreased flowering frequency. Fruit set decreased with increasing coverage of competitive species and seed production per capsule decreased with increasing soil nitrogen content. -

The Royal Court Annual Report

THE ROYAL COU rt THE ROYAL COUrt A NNUAL REPO ANNUAL REPOrt THE ROYAL COUrt rt The Royal Palace of Stockholm 2008 2008 111 30 Stockholm Tel: 08-402 60 00 www.kungahuset.se CONTENTS THE YEAR IN BRIEF ...................................................................4 CARL XVI GUSTAF – SWEDEN’S HEAD OF STATE .................5 REPORT FROM THE MARSHAL OF THE REALM ........................ 6 ROYAL COURT For Sweden – With the Times ........................................................................7 Financial reporting ........................................................................................ 7 The Court Administration’s use of funds ...................................................... 8 Staff ...............................................................................................................9 THE COURT ADMINISTRATION Offi ce of the Marshal of the Realm ..............................................................10 Offi ce of the Marshal of the Court with Offi ce of Ceremonies ...................12 H.M. The Queen’s Household .....................................................................16 H.R.H. The Crown Princess’s Household ................................................... 19 H.R.H. The Duchess of Halland’s Household ..............................................21 The Royal Mews ......................................................................................... 22 THE PALACE ADMINISTRATION The Royal Collections with the Bernadotte Library .................................... 24 The Offi