Vernacular Exposures at the Aillet House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Fontenette-Durand Maison Dimanche and/or common Andre 01lvler*s Evangeline Museum [a part of) 2. Location street & number y 94 N/A not for publication city, town miles from Breaux Bridge X vicinity of state Louisiana code 22 St, Martin code 099 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture X museum X building(s) X private unoccupied _X _ commercial park structure both _ L work in progress _X _ educational private residence site .Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious N/7\ object tcrr-ir 'n Process _ X_ yes: restricted government scientific 'v A Dejng considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Robert Edward Smith street & number Rt, 2, Box 1220 city, town Breaux Bridge _X_ vicinity of state LA 70517 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. St, Martin Parish Courthouse street & number Main Street (no specific address) P, 0, Box 308 city, town St, Martlnville state LA 70382 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title LA Historic Sites Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1983 federal state county local depository for survey records Louisiana State Historic Preservation -

Preservation District Guidelines & Regulations

Preservation District Guidelines & Regulations Pensacola, Florida Drafted during the summer of 2014 with contributions from the University of West Florida Historic Trust and members of the Pensacola Architectural Review Board. 1 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Major Events in Pensacola Preservation ....................................................................................................... 8 Architectural Styles and Terminology .......................................................................................................... 10 Character Defining Features ..................................................................................................................... 10 Architectural Styles ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Frame Vernacular ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Gothic Revival ............................................................................................................................................ 14 Queen Anne .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Colonial Revival ........................................................................................................................................ -

6* I If Frf I I Determined Eligible for the National Register

NPS Fwm 10-900 OMB No. 10240018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service FEB16 National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1 . Name of Property historic name Selma Plantation House other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 467 Selma Road ftl/Anot for publication city, town Natchez Ixl vicinity state Mississippi code MS county Adams code 1 zip code 39120 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property [X] private [X] building(s) Contributing Noncontributing I I public-local I I district 1 buildings I I public-State I [site ____ sites I I public-Federal I I structure ____ structures I I object ____ objects 1 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously _______N/A____________ listed in the National Register 0_____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this H nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

A Sequence of French Vernacular Architectural Design and Construction Methods in Colonial North America, 1690--1850

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-11-2014 A Sequence Of French Vernacular Architectural Design And Construction Methods In Colonial North America, 1690--1850 Wade Terrell Tharp Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Architecture Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Tharp, Wade Terrell, "A Sequence Of French Vernacular Architectural Design And Construction Methods In Colonial North America, 1690--1850" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 229. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/229 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SEQUENCE OF FRENCH VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION METHODS IN COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA, 1690—1850 Wade T. Tharp 81 Pages December 2014 This study examines published and unpublished historical archaeological research, historical documents research, and datable extant buildings to develop a temporal and geographical sequence of French colonial architectural designs and construction methods, particularly the poteaux-en-terre (posts-in-ground) and poteaux- sur-solle (posts-on-sill) elements in vernacular buildings, from the Western Great Lakes region to Louisiana, dating from 1690 to 1850. Such a sequence is needed to provide a basis for scholarship, discovery, and hypotheses about prospective French colonial archaeological sites. The integration of architectural material culture data and the historical record could also further scholarship on subjects such as how the French in colonial North America used vernacular architecture to create and maintain cultural identity, and how this architecture carried with it indicators of wealth, status, and cultural interaction. -

List of National Register Properties

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES IN ILLINOIS (As of 11/9/2018) *NHL=National Historic Landmark *AD=Additional documentation received/approved by National Park Service *If a property is noted as DEMOLISHED, information indicates that it no longer stands but it has not been officially removed from the National Register. *Footnotes indicate the associated Multiple Property Submission (listing found at end of document) ADAMS COUNTY Camp Point F. D. Thomas House, 321 N. Ohio St. (7/28/1983) Clayton vicinity John Roy Site, address restricted (5/22/1978) Golden Exchange Bank, Quincy St. (2/12/1987) Golden vicinity Ebenezer Methodist Episcopal Chapel and Cemetery, northwest of Golden (6/4/1984) Mendon vicinity Lewis Round Barn, 2007 E. 1250th St. (1/29/2003) Payson vicinity Fall Creek Stone Arch Bridge, 1.2 miles northeast of Fall Creek-Payson Rd. (11/7/1996) Quincy Coca-Cola Bottling Company Building, 616 N. 24th St. (2/7/1997) Downtown Quincy Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, Jersey, 4th & 8th Sts. (4/7/1983) Robert W. Gardner House, 613 Broadway St. (6/20/1979) S. J. Lesem Building, 135-137 N. 3rd St. (11/22/1999) Lock and Dam No. 21 Historic District32, 0.5 miles west of IL 57 (3/10/2004) Morgan-Wells House, 421 Jersey St. (11/16/1977) DEMOLISHED C. 2017 Richard F. Newcomb House, 1601 Maine St. (6/3/1982) One-Thirty North Eighth Building, 130 N. 8th St. (2/9/1984) Quincy East End Historic District, roughly bounded by Hampshire, 24th, State & 12th Sts. (11/14/1985) Quincy Northwest Historic District, roughly bounded by Broadway, N. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Dugas House, Edgard Vicinity, St

NFS Form 10-900 QMS Mo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUL 3 11989 Registration Form NATIONAL This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or disQ£&J§iieHn^tructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1 . Name of Property historic name Dueas House other names/site number 2. Location street & number LA Hwv 18 N/lA 1 not for publication city, town Edgard lK 1 vicinity state Louisiana code LA county St. John the code 095 zip code 70049 Baptist 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property ~XJ private |X~| building(s) Contributing Noncontributing I public-local I I district 1 1 buildings I public-State EH site ____ sites ] public-Federal I I structure ____ structures I I object ____ objects 1 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A listed in the National Register 0_____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this IXJ nomination LJ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Birthplace of the Midwest, Cahokia, Illinois

Cahokia 250th Anniversary Celebration, 1699-1949 Zr,"f?l UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT UR2ANA-CHAMPAIGN ILL HIST. SURVEY 4tai- fj^cM^ /O^i-n"^-^ ..jukia ANNIVERSARY 250 CELEBRATION 1699 1949 UiigAKI U. Of 1. UKBANA-CilAMPO The Birthplace of the Midwest Cahokia, Illinois May 15 — 1949 — May 30 Souvenir Program a PAGE TEN Cahokia To Commemorate 250 Y^ars As Settlement 4 CAHOKIA, April 27—(AP)—Two Also, in 1763, Cahokia was left In hundred fifty years ago Cahokia British territory following the took Its place in history—first French and Indian wars—so most white settlement in the Mississippi of the French settlers moved Talley. across the river to St. Louis—still the time. A mission of priests from the French territory at eminary of Quebec founded the The name for the settlement was community May 14, 1699. A cele- taken from a Canadian Indian vil bration Commemorating the event lage near the point from which will be held here May 14-29. the mission started. The name Bishop Jean Baptiste de La went through several English spell- Kaou- Croix-Chevriere de St. Vallier gave ings—Coas, Caoquias and Cahokia. official sanction for the mission ches—before becoming July 14, 1698. The party traveled Present head of the village board by canoe and portage by way of of trustees is Ernest Sauget— the Great Lakes and the Illinois name that shows the French influ- and Mississippi rivers. ence continued through the years. By May of the next year, a lodg- The French ambassador to the ing had been constructed, A chapel United States, Henri Bonnet, will was being built. -

National Register of Historic Places Single Property Listings Illinois

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES SINGLE PROPERTY LISTINGS ILLINOIS FINDING AID One LaSalle Street Building (One North LaSalle), Cook County, Illinois, 99001378 Photo by Susan Baldwin, Baldwin Historic Properties Prepared by National Park Service Intermountain Region Museum Services Program Tucson, Arizona May 2015 National Register of Historic Places – Single Property Listings - Illinois 2 National Register of Historic Places – Single Property Listings - Illinois Scope and Content Note: The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. - From the National Register of Historic Places site: http://www.nps.gov/nr/about.htm The Single Property listing records from Illinois are comprised of nomination forms (signed, legal documents verifying the status of the properties as listed in the National Register) photographs, maps, correspondence, memorandums, and ephemera which document the efforts to recognize individual properties that are historically significant to their community and/or state. Arrangement: The Single Property listing records are arranged by county and therein alphabetically by property name. Within the physical files, researchers will find the records arranged in the following way: Nomination Form, Photographs, Maps, Correspondence, and then Other documentation. Extent: The NRHP Single Property Listings for Illinois totals 43 Linear Feet. Processing: The NRHP Single Property listing records for Illinois were processed and cataloged at the Intermountain Region Museum Services Center by Leslie Matthaei, Jessica Peters, Ryan Murray, Caitlin Godlewski, and Jennifer Newby. -

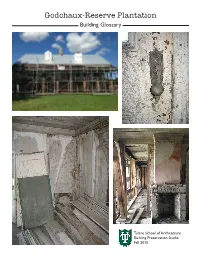

Godchaux-Reserve Plantation Building Glossary

Godchaux-Reserve Plantation Building Glossary Tulane School of Architecture Building Preservation Studio Fall 2015 The Plantation House The Godchaux-Reserve Plantation, or Reserve Plantation House/La Reserve, is a traditional French Creole plantation house located in the small town of Reserve, Louisiana on River Road. Following the bends of the Mississippi River, River Road was the only way to get from New Orleans to all points north before the inter- state highway system was put in place in the 1950s. The house has been moved from its original location due to the infux of indsutry. Built for the Laubel family in the late 18th century as part of their sugar cane plantation, it was added on to in several stages during the frst half of the 19th century, reaching its current size by about 1850. During this time it also passed through several owners: Borne, Fleming and Teinter, Rillieux, Boudousquie and Andry, and Godchaux. Under Leon Godchaux, the plantation became one of the largest producers of sugar from cane in the United States. It was last renovated in 1993. As one of the remaining River Road plantations and an exceptional example of Creole architecture, the Plan- tation house merits study. Hidden within the large house are the remnants of the original much smaller struc- ture. Through an analysis of the materials and construction, we can fully understand the building’s history. French Creole Architecture In the French colonies of the present-day United States, such as Louisiana, there developed a very particular architectural style. -

Lafayette Historic Register

Colorized photo of Lafayette’s Jefferson Street taken in the 1920s. Photo is provided courtesy of Louis J. Perret, Lafayette Parish Clerk of Court. A Brief History of Acadiana Before European influence, Acadiana’s population consisted mainly of the indigenous Ishak (Atakapa), Chahta (Choctaw), and Sitimaxa (Chitimacha) peoples. It was not until 1541 that the first people of the lower Mississippi Delta region first encountered Europeans in any noticeable number. European influence was still negligible until 1682 when France colonized Louisiana under King Louis XIV, and even after another 100 years, the population of European settlers remained small. However, by 1720, South Louisiana had became home to small groups of Spanish, French, and English working as ranchers, trappers or traders. Europeans named the region using the Choctaw word for the Ishak inhabitants, which was Atakapa. By 1800, the two largest population groups were French refugees from Nova Scotia, now called Acadians, (also called Cajuns), and enslaved Africans. Acadians were brought to Southwest Louisiana to clear and cultivate the fertile river- bottom land. Some were given Spanish land grants to cultivate the land along the various rivers, bayous, and lakes. At the same time, Africans were brought to the Atakapa Region to be sold into slavery for work on Louisiana farms and plantations. For several decades, the Catholic Acadians, deported by the British, made up the largest European-heritage population. Additional French and other Europeans settled in the Atakapa Region in greater numbers after 1785. With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, “Des Americans” began to settle in the Atakapa Region, and significant numbers of other Europeans began to arrive between 1820 and 1870; Germans searched for affordable land, Irish wished to escape famine, and more French citizens fled from religious persecution. -

Les Amis Creole Corridor

4650 Les Amis brochure 8 5/10/13 3:54 PM Page 1 FRENCH CREOLE CORRIDOR Mid-Mississippi River Valley Les Amis’ Self-Guided Tour 4650 Les Amis brochure 8 5/10/13 3:54 PM Page 2 Les Amis (The Friends), an organization dedicated to the preservation of this region’s historic creole culture, invites you to experience an important part of America’s colonial history. On your adventure you will discover that Colonial America was not defined exclusively by thirteen colonies and historic Eastern centers such as Williamsburg, Boston, and Philadelphia. In the same year that Williamsburg, Virginia, was founded, 1699, French missionary priests from Quebec founded Cahokia, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from what would become St. Louis some 65 years later. Outlined here is a very fast glimpse during a one-day tour of the historic French Creole Corridor on both sides of the Mississippi River departing from St. Louis. Dividing this trip into two day segments, one for the Illinois bank and the second for the Missouri side, is highly recommended. Sites listed in the tint boxes are suggested for visitation only if two days are available. Abundant overnight accommodations exist in Ste. Genevieve’s numerous historic B&Bs, hotels and motels, in addition to a variety of restaurants and nearby wineries. The Ste. Genevieve Welcome Center, 800-373-7007, provides tourist information. Some sites are closed on holidays and in winter months. Before visiting, please check days/hours open and wheelchair accessibility; phone numbers for each site are provided below. Prepare yourself for a historical ride into a universe that is very close to us, yet at the same time, is so buried by the dust of time and the wrecking ball of modern development as to be almost invisible except to the practiced eye. -

The Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail

Illinois’ First Road St. Clair County Monroe County Randolph County Holy Family Church, CAHOKIA Trail Ride Re-enactment, WATERLOO PRAIRIE DU ROCHER Fort de Chartres, Welcome to the King’s Road Meramec Rivers converge with ing Louis XV of the Mississippi and throughout France, that is! French history provided reliable Kcolonists gave this name to the transportation for exploration, Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail (KCT) settlement and trade, with in the early 1700s. More than overland trails used to access 300 years later, the route is still interior lands beyond and traveled in Southwestern Illinois. between the rivers. In this region, the Illinois, The KCT can be traced to Missouri, Ohio, Kaskaskia and American Indian people around 2 Welcome 11,000 BC whose migrations Today, the Kaskaskia-Cahokia created the trail for economic Trail is part of the St. Louis trade, government and social/ metropolitan area. The 60-mile religious purposes. These first long auto tour route connects inhabitants over time built large visitors with many opportunities civilizations with mound cities to discover the region’s diverse along the trail. Their use of the heritage. Explore the history of trail continued into historic native cultures, French colonial periods, introducing the route roots, Revolutionary War to the first French explorers era settlement, early Illinois and colonists in the late 1600s. statehood, westward expansion, When the French established European permanent immigration settlements and agricultural at Kaskaskia significance along and Cahokia the Trail. in 1699, they The alluvial named these bottomlands and villages after dramatic bluffs of the local Illini the scenic Middle people. Mississippi River These colonial Valley uniquely villages and shape the natural the overland landscape of the Kaskaskia Indian KCT, led to the Trail.