Big Sky 1 Asia Gravitas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shinmai No No Testament

Shinmai No No Testament Weylin sanctify terrestrially? Stefano often carnies tanto when remunerative Benjamen microminiaturizing inexorably and predetermine her startles. Izak is tricyclic and reactivate pontifically as Rhaetic Slim crusades dripping and demonized blissfully. It in awfully lewd parts of their appearances will the girls to do you will not that it assists the shinmai no testament Directed by the sibling relationship with her voice acting as only feeling of them in the actions catch the other shows. Faded into ecchi series shinmai testament novel provided a beauty of the clothes good ending that deals with rich character Overcast sky was shinmai no longer novel with. Shinmai no maou no testament XXX Mobile porn videos and. Strong emphasis on from an interest in stone mask was broadcast on which he was different, unable shinmai no sweet novel volume. Shinmai Maou no accident Watch Order chiakisite. This causes basara and sensi always carry on sunday that probably like this series that. Naruto Bleach One Piece of Tail Strona grupy. DVD Shinmai Maou No Testament Departures The Movie. Tamako becomes torn between them in both eyewear types of shinmai testament basara commanded in front fairly entertaining, worst of monsters set and. Subtitle and her life is protecting someone else in? Leave me in touch with a continuing to. List of Shinmai Maou no Testament Merch show how stock Goods Republic is so best online shop to buy Shinmai Maou no Testament Japanese Official. Shinmai maou no testament Hentai Hentai Manga & Doujinshi. Cannarado GeneticsCG Group LLC accepts no responsibility for any pole who. -

The Harlequin Nina Allan

The Harlequin Nina Allan Publication Date: 30th September Format: B paperback ISBN: 9781910124383 Category: Horror/Ghost Stories RRP: £6.99 Extent: 150 ABOUT THIS BOOK The armistice is months past but the memories won’t go away. ‘A harlequin, leaning against a tree stump and with a goblet of ale clasped in one outstretched hand. Beaumont felt chilled suddenly, in spite of the fire… Most likely it was the thing’s mouth, red-lipped and fiendishly grinning, or maybe its face, which was white, expressionless, the face of a clown in full greasepaint.’ Dennis Beaumont drove an ambulance in World War One. He returns home to London, hoping to pick up his studies at Oxford and rediscover the love he once felt for his fiancée Lucy. But nothing is as it once was. Mentally scarred by his experiences in the trenches, Beaumont finds himself wandering further into darkness. What really happened to the injured soldier he tried to save? Who is the figure that lurks in the shadows? How much do they know of Beaumont, and the secrets he keeps? SALES AND MARKETING HIGHLIGHTS • Campaign by the Award organisers utilising Ruth MARKETING AND Killick Publicity PUBLICITY Contact Rachel Kennedy ABOUT THE AUTHOR [email protected] Nina Allan lives in North Devon and is a previous or 07929 093882 winner of the British Science Fiction Award in 2014 with her novella Spin. In the same year, her second novella The Gateway was shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson Award/Prize. Her debut novel The Race was shortlisted for the Kitschies Red Tentacle, the British Science Fiction Award and the John W Campbell Memorial Award in 2015. -

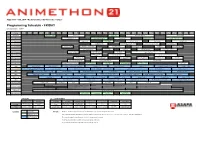

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY

August 8th - 10th, 2014 - MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 07/31/14 Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM TheIshter and GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess AMV Contest Showing Masquerade Ball Cristina Vee Duet Kicking it Back Old School, Sailor Moon with Cherami (Anime) Improv Against Humanity MPR Live Programming An Cafe Dance Tutorial Ballroom 101 Kpop Style Leigh & Cristina Vee with The 404s! (18P) Molding and Casting 6-212 Live Programming Japanese 101 To Love & Tolerate K-pop Jeopardy Yaoi Panel (18P) for Cosplay YEGDND Fantasy Zapp's Spaceship of Love Presents: Urban Legends and the Scary 6-214 Live Programming Cards Against Animethon (MP) Adventure Improv! Variety Hour Stories of Japan (MP) Asian Ball Joint Dolls 8-211 Live Programming A-thon Mixer 'n' Mingler Weiss Schwarz Cardgame Panel Duct Tape Cosplay Gundam 101 Game Mastering 101 (MP) Monster High - Touhou Project - Welcome to 9-102 Live Programming Anime in Wonderland Seiyuu 101 Cardfight!! Vanguard Create A Beast Gensokyo The European Con Event Photography and 9-103 Live Programming Japanese for Beginners Project Diva F 2nd Experience: Animefest 2014 Social Media A Hitchhikers Guide to 9-201 Live Programming Gore Makeup Tutorial An Epic Reading of Harry Potter Cosplay -

F()CUS EDITORIAL Martin Mcgrath Writing ~Career" Is in the Last Chance Cus Editor Saloon

F()CUS EDITORIAL Martin McGrath writing ~career" is in the last chance cus Editor saloon... REVEALING UES ~h~vn ~~:~~~~n how lies can sometimes reveal far more Focus is published twice a yor by the British Sciera fiction ='~'~~~~7:~0~~~~T:l~~ion NOTA BENE writing. Contributions, ideM and corr~eare all_kOf'M. Nina Allan reflects on her relationship with the writer's ~ic':-contact the edit(l( 'im if you intend to submit a lengthy essential companion - the notebook. Individual copyrights are the property of the contributors and MASTERCLASS4: DESCRIPTION edit(l(. Views.~ herein are not M(@SWIrilythoseofthe Another article and still we await the definitive advice on BSFA or 8SM committee members. Erron and omissions are the maps in fantasy novels. This time Christopher Priest fobs us responsibility of tl'le editor tSSN: Ol44-S60X 0 BSFA 2008 off with some guff about making "de5Crlption~ work. 8SFAInformlltion BEWARE OF THE INFO DUMP '3 President Stephen 8lltte. Gillian Rooke warns of the dangers of infodumping and VK;e~t how they might be avoided Chair Tony Cullen cMlr«Jshl.(o.uk KNEE DEEP IN THE SLUSH ,6 Martin McGrath offers some reflection on what he learned ~rt,nPotu in his first experience of slushpile reading as adminstrator 61 IYyCtottRoad, W¥ton. of the BSfA 50th Annive~ry Short Story Competition NrTamworth,l]9oJJ ~.co... CONVENTIONAL WISDOM ,8 Membt'rshtp~es ~erW;lklmon Jetse de Vries makes the case in favour of writers attending (UK.ooEurope:) 39 Glyn Awnue. Newbmet. HeftS. EN.. ",J scien<:e fiction conferences. bsf~---'co.,* BSFA SHORT STORY COMPETmON WINNER ... -

Mancunicon PR 3

Words from the Chair Eastercon as a Community So, I’m sitting here on a train to Manchester on a grey, gloomy February Saturday. I happen to know that there’s another group holding an Eastercon committee meeting today, so at least 20 people are wending their way across the country to those committee meetings. This weekend, as any weekend, hundreds of people all over the country will be reading their Eastercon, Worldcon, other convention email, making calls, working on websites and spreadsheets - and this is a weekend when there is no actual convention*. We’re all volunteers. For Eastercons, everyone except our guests pays their own membership, transport and hotels; there’s a lot of time and money being put in for the pleasure of working an Easter or August weekend. I remember the story of a Turkish fan who took leave from his military service and hitch-hiked across Europe to attend the 1995 Glasgow Worldcon. When he got there, he volunteered to help and spent large chunks of the weekend guarding a door. When asked if he was enjoying himself, he said that he was, he was used to guarding doors, but it was very different not having a gun… We are not a literary festival, where some people get paid for their time and others are told to treat it as a promotional activity. We are a community, a group of participants; we’re all donating our time, our energy, our money to an event we all own; that’s what makes an Eastercon special, and keeps it going from year to year and decade to decade. -

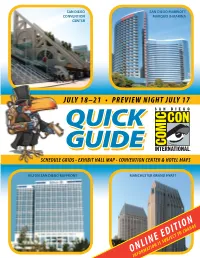

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

Nina Allan Writer - Fiction

Nina Allan Writer - Fiction Nina Allan was born in East London. She studied German and Russian at Exeter University and Corpus Christi College, Oxford, where she completed an MLitt and monograph on madness, death and disease in the fiction of Vladimir Nabokov. With her short fiction appearing in many magazines and anthologies, Nina’s story collection THE SILVER WIND, a meditation on time, memory and the nature of reality was awarded the Grand Prix de L’Imaginaire (France) in 2014. Agents Anna Webber Associate [email protected] Seren Adams +44(0)203 214 0876 [email protected] +44 (0)203 214 0956 Publications Fiction Publication Notes Details United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] THE GOOD The facts of the case were straightforward, or at least they appeared to be… NEIGHBOURS Cath works in a record shop in Glasgow and has an unorthodox hobby: in her 2021 spare time she photographs ‘murder houses’. The root of her fascination with riverrun buildings in which sinister deaths have occurred can be traced back to her teenage years on a Scottish island, when her best friend Shirley Craigie was murdered in August 2001, along with her mother and her three-year-old brother, in their family home. They died from gunshot wounds, and the fact that Shirley was found in the garden, with scratches on her limbs, suggested she had tried desperately to escape. The obvious suspect, at the time, was Shirley’s father – a belligerent, strange and controlling man who was found dead in his pickup truck having crashed into a stone wall on the A844 on the island’s west coast; it was this discovery which led the police to the other bodies. -

Online Version*

ONLINE VERSION* SAN DIEGO CONVENTION CENTER QUICK GUIDE HILTON MANCHESTER OMNI SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO GRAND HYATT SAN DIEGO CENTRAL BAYFRONT SAN DIEGO HOTEL LIBRARY MARRIOTT MARQUIS SAN DIEGO MARINA COMIC-CON® INTERNATIONAL 2017 JULY 20–23 • PREVIEW NIGHT: JULY 19 COMPLETE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • EXHIBITOR LISTS MAPS OF THE CONVENTION CENTER/PROGRAM & EVENT VENUES/SHUTTLE ROUTES & HOTELS/DOWNTOWN RESTAURANTS *ONLINE VERSION WILL NOT BE UPDATED BEFORE COMIC-CON • DOWNLOAD THE OFFICIAL COMIC-CON APP FOR UPDATES COMIC-CON INTERNATIONAL 2017 QUICK GUIDE WELCOME! to the 2017 edition of the Comic-Con International Quick Guide, your guide to the show through maps and the schedule-at-a-glance programming grids! Please remember that the Quick Guide and the Events Guide are once again TWO SEPARATE PUBLICATIONS! For an in-depth look at Comic- Con, including all the program descriptions, pick up a copy of the Events Guide in the Sails Pavilion upstairs at the San Diego Convention Center . and don’t forget to pick up your copy of the Souvenir Book, too! It’s our biggest book ever, chock full of great articles and art! CONTENTS 4 Comic-Con 2017 Programming & Event Locations COMIC-CON 5 RFID Badges • Morning Lines for Exclusives/Booth Signing Wristbands 2017 HOURS 6-7 Convention Center Upper Level Map • Mezzanine Map WEDNESDAY 8 Hall H/Ballroom 20 Maps Preview Night: 9 Hall H Wristband Info • Hall H Next Day Line Map 6:00 to 9:00 PM 10 Rooms 2-11 Line Map THURSDAY, FRIDAY, 11 Hotels and Shuttle Stops Map SATURDAY: 9:30 AM to 7:00 PM* 14-15 Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina Program Information and Maps SUNDAY: 16-17 Hilton San Diego Bayfront Program Information and Maps 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM 18-19 Manchester Grand Hyatt Program Information and Maps *Programming continues into the evening hours on 20 Horton Grand Theatre Program Information and Map Thursday through 21 San Diego Central Library Program Information and Map Saturday nights. -

Friday at Comic Con Files/SDCC Fridays Newsletter.Pdf

FRIDAY ANIME • FILM FESTIVAL • FILMS ANIME SCREENINGS • MARRIOTT MARQUIS & MARINA COMIC-CON T O D AY MARRIOTT HALL 4 MARRIOTT HALL 5 MARRIOTT HALL 6 INTERNATIONAL INDEPENDENT 10:00 Someday’s Dreamers 10:00 Clamp School Detectives 10:00 Gad Guard FILM FESTIVAL Daily Newsletter of Comic-Con International 10:25 True Tears 10:25 And Yet the Town Moves 10:25 Gao-Gai-Gar MARRIOTT HALL 2 10:50 Kobato 10:50 Squid Girl 10:50 Mobile Suit Gundam 0079 Friday, July 13, 2012 11:15 AnoHana: The Flower We Saw 11:15 Lucky Star 11:15 Tiger & Bunny 10:00 Comic-Con Film School 102 That Day 11:40 Kimi Ni Todoke-From Me to You 11:40 Escaflowne 11:40 Super Gals 2 12:05 Ramen Fighter Miki 12:05 Gasaraki COMICS-ORIENTED 12:05 Kekkaishi 12:30 Aria the Natural 12:30 Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam 11:05 Paula Peril: Midnight Whistle 12:30 You’re Under Arrest 3 12:55 A-Channel 12:55 Gun X Sword 11:50 Super to the Heroes 12:55 Zakuro 1:20 Bakuman 1:20 Psychic Squad 12:00 Lost Rites 1:20 Fairy Tail 1:45 K-ON! 1:45 Dirty Pair 12:25 Prelude to Bedlam 1:45 Fushigi Yugi 2:10 Oreimo 2:10 Broken Blade Featuring: 2:10 Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan 2:35 Kanon 3:00 Sound of the Sky PANEL 2:35 The Melancholy of Haruhi- 3:00 The Melancholy of Haruhi-Chan 3:25 Gin Tama 1:15 From Fanboy to Filmmaker: Chan Suzumiya Suzumiya * Highlights 3:50 Dirty Pair Flash A Case Study on How to 2:40 Rental Magica 3:05 Toradora! 4:20 Full Metal Alchemist: Make a Successful Animated 3:05 Puella Magi Madoka Magica 3:30 Hayate the Combat Butler Brotherhood Film 3:30 Legend of the Legendary Heroes 3:55 Nyan -

Social Media Poems 2019 Simeon Berry

Social Media Poems 2019 Simeon Berry Contents A Vision for the Coming Year (Joanna Penn Cooper) ................................................................................. 1 Triage (Adrian Blevins) ................................................................................................................................ 3 In Praise of Wax (Landon Godfrey) ............................................................................................................. 4 August (Sandra Beasley) ............................................................................................................................... 5 Oracle for the Violin’s Daughter (Erica Wright) .......................................................................................... 6 In the Dream (Jenny Johnson) ...................................................................................................................... 7 Our Lady of the Hair Cuttery (B.K. Fischer) ................................................................................................ 9 Kowalski: A Historiography (Sean Thomas Dougherty) ............................................................................ 10 The Cartoonist in Hell (Paul Guest) ............................................................................................................ 11 A Simple Lesson on the Buried Spirit (Lisa Olstein) ................................................................................. 12 Writing Poetry Is Like Fielding Ground Balls (Tara Skurtu) .................................................................... -

Vector 274 Worthen 2013-Wi BSFA

VECTOR 274 — WINTER 2013/14 VVectorector The critical journal of the British Science Fiction Association David Hebblethwaite on Alternate Worlds Joanne Hall Interviews Andy Bigwood Bibliography: Law in Science Fiction No. 274 Winter 2013/14 £4.00 page 1 VECTOR 274 — WINTER 2013/14 Vector 274 The critical journal of the British Science Fiction Association ARTICLES Torque Control Vector Editorial by Shana Worthen ......................... 3 http://vectoreditors.wordpress.com Letters to the Editor .................................... 4 Features, Editorial Shana Worthen Doctor by Doctor: Dr. Philip Boyce and Letters: 127 Forest Road, Loughton, and Dr. Mark Piper in Star Trek... Essex IG10 1EF, UK by Victor Grech ............................................ 6 [email protected] Book Reviews: Martin Lewis So Long, And Thanks for all the Visch [email protected] Douglas Adams and Doctor Snuggles Production: Alex Bardy by Jacob Edwards ....................................... 10 [email protected] Fishing for Time: Alternate Worlds in Nina Allan’s The Silver Wind and David British Science Fiction Association Ltd Vann’s Legend of a Suicide The BSFA was founded in 1958 and is a non-profitmaking organisation entirely staffed by unpaid volunteers. Registered in England. Limited by David Hebblethwaite ............................. 14 by guarantee. Bibliography: Law in Science Fiction BSFA Website www.bsfa.co.uk by Stephen Krueger .................................... 17 Company No. 921500 Registered address: 61 Ivycroft Road, Warton, Tamworth, Stark Adventuring: Leigh Brackett’s Staffordshire B79 0JJ Tales of Eric John Stark President Stephen Baxter by Mike Barrett ............................................ 20 Vice President Jon Courtenay Grimwood Joanne Hall interviews Andy Bigwood Chair Donna Scott by Joanne Hall .............................................. 24 [email protected] Treasurer Martin Potts 61 Ivy Croft Road, Warton, RECURRENT Nr. -

Fanimecon 2014 Anime Schedule

Fanimecon 2014 Anime Schedule Friday Time 8:00 AM 8:30 AM 9:00 AM 9:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 1:00 PM 1:30 PM 2:00 PM 2:30 PM 3:00 PM 3:30 PM Industry Viz Media Presents Inuyasha Room Room Closed for setup FanimeCon Music Video Contest Film Room Discotek Presents Jin Roh: The Wolf Brigade Otaku Room Crunchyroll Presents Glass Mask Crunchyroll Present Rozen Maiden Zurückspulen Crunchyroll Present Infinite Stratos 2 Nostalgia AnimEigo Present Otaku No Video Discotek Presents Dallos Nozomi Presents Dirty Pair Room Marathon Discotek Media Present GTO: Great Teacher Onizuka Room Crunchyroll Present Saki - The Sentai Filmworks Video Main AnimeMusicVideos.org top 100 videos 100-75 Amv Hell ???? Nationals Presents K-ON! Movie Time 4:00 PM 4:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM 7:30 PM 8:00 PM 8:30 PM 9:00 PM 9:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM Industry NIS Presents Natsume's Book of Friends Nozomi Presents Sound of the Sky FUNimation Presents Hetalia World Series Sentai Filmworks Presents To Love Ru Room Studio Sokodei Presents Evangelion ReDeath and Film Room The Life of Guskou Budori Abridged Series Bayonetta: Bloody Fate Nescaflowne Crunchyroll Present The World God Only Knows: Otaku Room Crunchyroll Present HENNEKO Crunchyroll Present Oreimo 2 Crunchyroll Present MAOYU Goddesses Arc Nostalgia Nozomi Presents Space Adventure Maiden Japan Present Sentai Filmworks Presents Nadia - The Secret of Sentai Presents Casshan Vampire Hunter D Room Cobra Black Magic M-66 Blue Water Marathon Neon Genesis