1 Transformation of Political Elite in Azerbaijan a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Cultural Grounds in Formation and Growth of Ethnic Challenges in Azerbaijan, Iran

Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies Copyright 2018 2018, Vol. 5, No. 2, 64-76 ISSN: 2149-1291 A Study of the Cultural Grounds in Formation and Growth of Ethnic Challenges in Azerbaijan, Iran Mansour Salehi1, Bahram Navazeni2, Masoud Jafarinezhad3 This study has been conducted with the aim of finding the cultural bases of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan and tried to provide the desired solutions for managing ethnic diversity in Iran and proper policy making in order to respect the components and the culture of the people towards increasing national solidarity. In this regard, this study investigates the cultural grounds of the formation and growth of ethnic challenges created and will be created after the Constitutional Revolution in Azerbaijan, Iran. Accordingly, the main question is that what is the most influential cultural ground in formation and growth of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan? Research method was the in-depth interview, which was followed by an interview with 32 related experts, and after accessing all the results obtained, analysis of interview data and quotative analysis performed with in-depth interview. Findings of the research indicate that emphasis on the language of a country, cultural discrimination, and the non- implementation of Article 15 of the Constitution for the abandonment of Turkish speakers with 39% were the most important domestic cultural ground, and the impact of satellite channels in Turkey and Republic of Azerbaijan with 32% and superior Turkish identity in the vicinity of Azerbaijan with 31%, were the most important external grounds in formation and growth of ethnic challenges in Azerbaijan in Iran. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

İlham Əliyev: Mən Jurnalistləri Vətənpərvərliyə Çağırıram

Heydər əliyev irsini ArAşdırmA mərkəzi HeydAr Alıyev HerıtAge reseArcH center ilham əliyev: “mən jurnalistləri vətənpərvərliyə çağırıram” ılham Aliyev: “ı challenge the journalists to patriotism” Bakı - 2010 “İlham Əliyev: Mən jurnalistləri vətənpərvərliyə çağırıram” kita- bı Heydər Əliyev İrsini Araşdırma Mərkəzinin və “Kaspi” qəzetinin birgə ərsəyə gətirdiyi və Azərbaycanda milli mətbuatın yaradılma- sının 135 illiyinə həsr etdikləri ikinci kitabdır. Kitabda Azərbaycan Respublikasının Prezidenti İlham Əliyevin milli mətbuatın 135 illik yubileyinin geniş qeyd edilməsi barəsində sərəncamından yubileyə qədər olan dövr ərzində dövlət səviyyəsində görülmüş tədbirlər iki dildə oxuculara çatdırılır. ISBN 978 - 9952 - 444 - 39 - 1 «Apostrof» Çap Evi © Heydər Əliyev İrsini Araşdırma Mərkəzi 2010 “Heydər əliyev irsini Araşdırma mərkəzinin nəşrləri” seri- yasının məsləhətçisi: Asəf Nadirov, Heydər Əliyev İrsini Araşdırma Mərkəzi Elmi-Redaksiya Şurası- nın sədri, Azərbaycan Milli Elmlər Akademiyasının həqiqi üzvü elmi məsləhətçi və ön sözün müəllifi: Əli Həsənov, Azərbaycan Respublikası Prezident Administrasiyası İctimai- siyasi məsələlər şöbəsinin müdiri, tarix elmləri doktoru, professor Buraxılışa məsul: Vurğun Süleymanov yaradıcı heyət: Fuad Babayev, Heydər Əliyev İrsini Araşdırma Mərkəzinin baş direktoru Natiq Məmmədli, “Kaspi” qəzetinin baş redaktoru Mətanət Babayeva Təmkin Məmmədli Gündüz Nəsibov cildin dizaynı: Cavanşir Əzizov səhifələmə: Elşən Ağayev Kitabda AzərTAc-ın, Azərbaycan Respublikası Prezidentinin rəsmi saytının (www.pre- sident.az) -

Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi-Journal of Turkish Researches Institute TAED-60, Eylül- September 2017 Erzurum ISSN-1300-9052

Dr., Azerbaycan Milli Bilimler Akademisinin Nahçıvan Bölümü, İncesenet, Dil ve Edebiyat Enstitüsü, Edebiyatşünaslık Bölümü, Nahçıvan-Azerbaycan. [email protected] ORCID ID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7450-2191 Türkiyat Araştırmaları Enstitüsü Dergisi-Journal of Turkish Researches Institute TAED-60, Eylül- September 2017 Erzurum ISSN-1300-9052 Makale Türü-Article Types : Araştırma Makalesi-Research Article Geliş Tarihi-Received Date : 15.12.2016 Kabul Tarihi-Accepted Date : 04.05.2017 Sayfa-Pages : 181-190 DOI- : http://dx.doi.org/10.14222/Turkiyat3697 www.turkiyatjournal.com http://dergipark.gov.tr/ataunitaed This article was checked by iThenticate. Öz Abstract Makalede XX yüzyıl Azerbaycan siyasi In the paper is considered the lecture fikrinin öncü siması, “Türkçülüğün Babası”, “Turks in the two West epics”, made by a ünlü yazar, gazeteci, eğitimci, ressam, prominent representative of the Azerbaijani romantik şair Ali Bey Hüseyinzade`nin public thought of the XX century, the “Father (1864-1940) 1926 yılında Bakü`de of Turkism”, famous writer, journalist, düzenlenmiş Birinci Türkoloji educator, artist romantic poet Ali Bey Kongresi`ndeki “Batı`nın İki Destanında Husseinzadeh (1864-1940) at the I Turkic Türk” isimli bildirisinden bahsediliyor. Bu Study Congress, carried out in Baku in 1926. bildiri zamanında çok büyük ilgiyle This lecture at the time aroused great interest, karşılanmış ve aynı yılda kitap halinde in the same year was published as a book and yayınlanarak kamuoyuna iletilmiştir. presented to the public. The report “Turks in “Batı`nın İki Destanında Türk” Portekiz şairi two poems of the West” is devoted to issues Kamoens`in “Luziada” ve İtalyan şairi T. related to the Turks in the works “Lusiads” of Tasso`nun “Kurtarılmış Kudüs” eserlerinde the Portuguese poet Camoes and “Liberated Türk ile münasebet meselelerini ele almıştır. -

Azerbaijan Pharmaceutical Country Profile

Azerbaijan PHARMACEUTICAL COUNTRY PROFILE Azerbaijan Pharmaceutical Country Profile Published by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with the World Health Organization 12/05/2011 Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced, or translated in full or in part, provided that the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold, or used in conjunction with commercial purposes or for profit. This document was produced with the support of the World Health Organization (WHO) Azerbaijan Country Office, and all reasonable precautions have been taken to verify the information contained herein. The published material does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization, and is being distributed without any warranty of any kind – either expressed or implied. The responsibility for interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. ii Foreword The 2011 Pharmaceutical Country Profile for Azerbaijan has been produced by the Ministry of Health, in collaboration with the World Health Organization. This document contains information on existing socio-economic and health- related conditions, resources; as well as on regulatory structures, processes and outcomes relating to the pharmaceutical sector in Azerbaijan. The compiled data comes from international sources (e.g. the World Health Statistics1,2), surveys conducted in the previous years and country level information collected in 2011. The sources of data for each piece of information are presented in the tables that can be found at the end of this document. On the behalf of the Ministry of Azerbaijan, I wish to express my appreciation to WHO Country Office in Azerbaijan for its contribution to the process of data collection and the development of this profile. -

Nonproliferation Approaches in the Caucasus

Report: Nonproliferation Approaches in the Caucasus NONPROLIFERATION APPROACHES IN THE CAUCASUS by Tamara C. Robinson Tamara C. Robinson is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. ecent reports of the vast oil deposits in the Caspian Caucasian nuclear-weapon-free zone. It also evaluates Sea region have focused international attention U.S. policy responses to existing regional proliferation Ron the importance of stability in the Caucasus. threats. While the desire to stem proliferation may exist Yet the nuclear materials and expertise in these often in all three republics, economic conditions and problems overlooked newly independent states (Georgia, Arme- with domestic policy implementation, as a result of weak nia, and Azerbaijan) also pose a problem of international statehood, may override this desire if the West does not concern on three levels. At the ground level, maintain- offer additional assistance to support and strengthen non- ing control over these materials and watching over sci- proliferation efforts. entific expertise are imperative, yet measures are lacking as in most regions of the former Soviet Union, including MATERIALS AND THEIR PROTECTION, Russia herself. At the domestic policy level, the politi- CONTROL, AND ACCOUNTING cal and economic instability of these states in transition hampers the strengthening of key institutions for the pre- In order to understand proliferation problems on the vention of proliferation and provides an environment ground level, it is imperative to take stock of the nuclear conducive to black market activities. At the regional materials and control over them in each of the Cauca- level, the Caucasus represent both a geostrategically vi- sian republics and to assume that material protection, tal conduit and buffer between Russia and the Middle control, and accounting (MPC & A) will help guard East and from the Caspian Sea to the West. -

Hamlet Isaxanli in Search of “Khazar”

Hamlet Isaxanli In Search of “Khazar” 2 In Search of "Khazar" The realities of events associated with the establishment and development of Khazar University have left indelible traces in my memory. I intend to pass these events to you in their entirety and in all sincerity. I hope I can relive together with you, readers, those days spent in ‘search of "Khazar". In Search of "Khazar" 3 CHAPTER 1 BETWEEN HEAVEN AND EARTH For a number of years I was familiarizing myself with different universities all over the world, whilst gathering my thoughts on science and education in my own country, Azerbaijan. These ideas and comparisons were taking a distinctive shape in my imagination - the shape of a university. Novel ideas and thoughts seemingly appear unexpectedly, but in reality they are a result of long and intensive subconscious efforts. The information that we absorb, accept and keep in our minds is explored and analyzed in invisible and imperceptible ways. Accor- ding to some hypotheses, this way is simply called a harmonization, putting thoughts into a correct and beautiful order. In this process, suddenly everything falls into place and an idea appears as a patch of light. The first place where I studied after Azerbaijan was Moscow State University. I spent long years there first studying and then researching mathematics. The university’s extremely high scientific potential and pleasant and creative atmosphere seemed to be a new world to me. Later I traveled more and came across more varied systems at universities in Canada and in Europe. I didn’t content myself solely with giving lectures, presenting papers at different conferences, workshops, and conducting new research. -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule. -

SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR

SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Aslan Ismayilov SUMGAYIT - BEGINNING OF THE COLLAPSE OF THE USSR 1 Aslan Ismayilov ЧАШЫОЬЛУ 2011 Aslan Ismayilov Sumgayit – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Baku Aslan Ismayilov Sumgayit – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Baku Translated by Vagif Ismayil and Vusal Kazimli 2 SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR SUMGAYIT PROCEEDINGS 3 Aslan Ismayilov 4 SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR HOW I WAS APPOINTED AS THE PUBLIC PROSECUTOR IN THE CASE AND OBTAINED INSIGHT OF IT Dear readers! Before I start telling you about Sumgayit events, which I firmly believe are of vital importance for Azerbaijan, and in the trial of which I represented the government, about peripeteia of this trial and other happenings which became echoes and continuation of the tragedy in Sumgayit, and finally about inferences I made about all the abovementioned as early as in 1989, I would like to give you some brief background about myself, in order to demonstrate you that I was not involved in the process occasionally and that my conclusions and position regarding the case are well grounded. Thus, after graduating from the Law Faculty of of the Kuban State University of Russia with honours, I was appointed to the Neftekumsk district court of the Stavropol region as an interne. After the lapse of some time I became the assistant for Mr Krasnoperov, the chairman of the court, who used to be the chairman of the Altay region court and was known as a good professional. The existing legislation at that time allowed two people’s assessors to participate in the court trials in the capacity of judges alongside with the actual judge. -

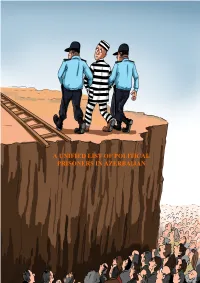

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Genocide and Deportation of Azerbaijanis

GENOCIDE AND DEPORTATION OF AZERBAIJANIS C O N T E N T S General information........................................................................................................................... 3 Resettlement of Armenians to Azerbaijani lands and its grave consequences ................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Iran ........................................................................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Turkey ................................................................................... 8 Massacre and deportation of Azerbaijanis at the beginning of the 20th century .......................... 10 The massacres of 1905-1906. ..................................................................................................... 10 General information ................................................................................................................... 10 Genocide of Moslem Turks through 1905-1906 in Karabagh ...................................................... 13 Genocide of 1918-1920 ............................................................................................................... 15 Genocide over Azerbaijani nation in March of 1918 ................................................................... 15 Massacres in Baku. March 1918................................................................................................. 20 Massacres in Erivan Province (1918-1920) ............................................................................... -

Climate Change and Security in the South Caucasus

CLIMATE CHANGE AND SECURITY IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA, REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN AND GEORGIA Regional Assessment ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PROJECT CO-ORDINATION Within the framework of the project Climate Change and Security in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and the Southern Caucasus under the Christine Kitzler, Dana Bogdan (OSCE) Environment and Security Initiative (ENVSEC), one of the four main activities aimed at identifying and mapping climate change and security risks in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and the South Caucasus in a participatory way, the conclusions of which are presented in the current report for the South Caucasus. ASSESSMENT CO-ORDINATION Harald Egerer, Pier Carlo Sandei, Filippo Montalbetti (UN Environment), Valentin Yemelin (GRID-Arendal) The Austrian Development Agency (ADA) has co-funded the project by providing financial resources for the project activities in the pilot region in the Dniester River Basin. Moreover, the ENVSEC initiative partners the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UN Environment, the United Nations Economic Commission for LEAD AUTHOR Europe (UNECE) and the Regional Environmental Centre for Central and Eastern Europe (REC) contributed their own resources to the Ieva Rucevska (GRID-Arendal) implementation of this project. CONTRIBUTORS AND REVIEWERS Nino Malashkhia (OSCE) Trine Kirkfeldt, Hanne Jørstad, Valentin Yemelin (GRID-Arnedal) Mahir Aliyev (UN Environment) Zsolt Lengyel (Climate East Policy) The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the ENVSEC partner organizations, their donors or the participating States. Participants in the national consultations that took place in the Republic of Armenia (Yerevan, 12 May 2014), the Republic of Azerbaijan (Baku, 30 May 2014) and in Georgia (Tbilisi, 8 May 2014) commented and contributed to the regional assessment.