Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POST BID SALE No. 22 Bids Close: Monday 21 September 2009

Robin Linke PB #22Cover.qxd:74541 R.Linke Book No21 17/8/09 3:26 PM Page 1 Robin Linke POST BID SALE No. 22 Bids Close: Monday 21 September 2009 Lot 1398 181 JERSEY STREET WEMBLEY 6014 WESTERN AUSTRALIA TELEPHONE: (08) 9387 5327 FAX:(08) 9387-1646 INTERNATIONAL: +61-8-9387-5327 FAX: +61-8-9387-1646 EMAIL: [email protected] Australasian 2009/10 Price List 50th Edition AUSTRALIA Page YVERT, MICHEL, SCOTT AND STANLEY GIBBONS CATALOGUE NUMBERS. PRICES IN AUSTRALIAN DOLLARS KANGAROOS 1-2 KGV HEADS 2-5 PRE-DECIMALS 5-7 DECIMALS 8-17 YEAR ALBUMS 18 BOOKLETS 8, 20, 21 OFFICIALS 8 FRAMAS 22 POSTAGE DUES 22-23 COIL PAIRS 7 SPECIMEN OPTS 2, 17 FIRST DAY COVERS 6-17 MAXIMUM CARDS 10-17 STATIONERY 25-29 COMPLETE COLLECTIONS 24, 43 WESTERN AUSTRALIA 30-32 ANTARCTIC 33 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 33-34 COCOS ISLANDS. 34-36 NAURU 43 NORFOLK ISLAND. 35-37 N.W.P.I. 38 NEW GUINEA 38 PAPUA 38-40 PAPUA NEW GUINEA 40-42 NEW ZEALAND 44-49 ROSS DEPENDENCY 49 Robin Linke 181 JERSEY STREET WEMBLEY 6014 WESTERN AUSTRALIA TELEPHONE: (08) 9387-5327 FAX: (08) 9387-1646 INTERNATIONAL: +618 9387-5327 FAX: +618 9387-1646 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.robinlinke.com.au AVAILABLE ON REQUEST 2009/10 � ROBIN LINKE POST BID NO. 22 181 JERSEY STREET PHONE: 08-9387-5327 INT: +61-8-9387-5327 50th Edition WEMBLEY 6014 FAX: 08-9387-1646 INT: +61-8-9387-1646 WESTERN AUSTRALIA E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http:www.robinlinke.com.au Please purchase the lots below at the lowest possible price in accordance with your Conditions of Sale Name: Date Address: Postcode Signed Phone No. -

Discrimination and Violence Against Women in Brunei Darussalam On

SOUTH Muara CHINA Bandar Seri SEA Begawan Tutong Bangar Seria Kuala Belait Sukang MALAYSIA MALAYSIA I N D 10 km O N E SIA Discrimination and Violence Against Women in Brunei Darussalam on the Basis of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Presented to the 59th Session of The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Discrimination and Violence Against Women in Brunei Darussalam on the Basis of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Presented to the 59th Session of The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) November 2014 • Geneva Submitted by: International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Syariah Penal Code Order 2013 ................................................................................................................... 1 Discrimination Against LBT Women (Articles 1 and 2) ............................................................................. 3 Criminalization of Lesbians and Bisexual Women ...................................................................................... 3 Criminalization of Transgender Persons ..................................................................................................... -

Introduction

Introduction The Islamic World Today in Historical Perspective In 2012, the year 1433 of the Muslim calendar, the Islamic popula- well as provincial capitals of the newly founded Islamic empire, such tion throughout the world was estimated at approximately a billion as Basra, Kufa, Aleppo, Qayrawan, Fez, Rayy (Tehran), Nishapur, and a half, representing about one- fifth of humanity. In geographi- and San‘a’, merged the legacy of the Arab tribal tradition with newly cal terms, Islam occupies the center of the world, stretching like a incorporated cultural trends. By religious conversion, whether fer- big belt across the globe from east to west. From Morocco to Mind- vent, formal, or forced, Islam integrated Christians of Greek, Syriac, anao, it encompasses countries of both the consumer North and the Coptic, and Latin rites and included large numbers of Jews, Zoroas- disadvantaged South. It sits at the crossroads of America, Europe, trians, Gnostics, and Manicheans. By ethnic assimilation, it absorbed and Russia on one side and Africa, India, and China on the other. a great variety of nations, whether through compacts, clientage and Historically, Islam is also at a crossroads, destined to play a world marriage, persuasion, and threat or through religious indifference, role in politics and to become the most prominent world religion social climbing, and the self- interest of newly conquered peoples. during the 21st century. Islam is thus not contained in any national It embraced Aramaic- , Persian- , and Berber- speaking peoples; ac- culture; -

Int Cedaw Ngo Brn 18687 E

UNITED NATIONS COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN 59th Session of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women 20 October – 7 November 2014 THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS’ SUBMISSION TO THE UN COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN IN ADVANCE OF THE EXAMINATION OF BRUNEI DARUSSALAM’S INITIAL AND SECOND PERIODIC REPORTS UNDER ARTICLE 18 OF THE CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN Submitted on 3 October 2014 Composed of 60 eminent judges and lawyers from all regions of the world, the International Commission of Jurists promotes and protects human rights through the Rule of Law, by using its unique legal expertise to develop and strengthen national and international justice systems. Established in 1952, active on the five continents, the ICJ aims to ensure the progressive development and effective implementation of international human rights and international humanitarian law; secure the realization of civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights; safeguard the separation of powers; and guarantee the independence of the judiciary and legal profession. P.O. Box, 91, Rue des Bains, 33, 1211 Geneva 8, Switzerland Tel: +41(0) 22 979 3800 – Fax: +41(0) 22 979 3801 – Website: http://www.icj.org E-mail: [email protected] Introduction 1. During its 59th session, from 20 October to 7 November 2014, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW or the Committee) will examine Brunei Darussalam’s implementation of the provisions of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (the Convention), including in light of the state party’s initial and second periodic reports.1 The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) welcomes the opportunity to submit the following observations to the Committee. -

De La Versatilité (5) Avatars Du Luth Gambus À Bornéo

De la versatilité (5) Avatars du luth Gambus à Bornéo D HEROUVILLE, Pierre Draft 2013-13.0 - Mars 2020 Résumé : le présent article a pour objet l’origine et la diffusion des luths monoxyles en Malaisie et en Indonésie, en se focalisant sur l’histoire des genres musicaux locaux. Mots clés : diaspora hadhrami, qanbus, gambus, gambus Banjar, gambus Brunei, panting, tingkilan, jogget gembira, marwas, mamanda, rantauan, zapin, kutai, bugis CHAPITRE 5 : LE GAMBUS A BORNEO L.F. HILARIAN s’est évertué à dater la diffusion chez les premiers malais du luth iranien Barbat , ou de son avatar supposé yéménite Qanbus vers les débuts de l’islam. En l’absence d’annales explicites sur l’instrument, sa recherche a constamment corrélé historiquement diffusion de l’Islam à introduction de l’instrument. Dans le cas de Bornéo Isl, [RASHID, 2010] cite néanmoins l’instrument dans l’apparat du sultan (Awang) ALAK BELATAR (d.1371 AD?), à une époque avérée de l’islamisation de Brunei par le sultanat de Johore. Or, le qanbus yéménite aurait probablement été (ré)introduit à Lamu, Zanzibar, en Malaisie et aux Comores par une vague d’émigration hadhramie tardive, ce qui n’exclut pas cette présence sporadique antérieure. Nous n’étayons cette hypothèse sur la relative constance organologique et dimensionnelle des instruments à partir du 19ème siècle. L’introduction dans ces contrées de la danse al-zafan et du tambour marwas, tous fréquemment associés au qanbus, indique également qu’il a été introduit comme un genre autant que comme un instrument. Nous inventorions la lutherie et les genres relatifs dans l’île de Bornéo. -

Islam in South-East Asia

Chapter 6 Islam in South-east Asia The great period of Islam in South-east Asia belongs to the distant rather than the recent past and came about through commerce rather than military conquest. Long before the advent of Islam, Arab merchants were trading with India for Eastern commodities — Arab sailors were the first to exploit the seasonal monsoon winds of the Indian Ocean — and it was commerce that first brought Arab traders and Islam to South-east Asia. The financial incentive for direct exchanges with the East was immense. The long journey to the market- place of most Oriental commodities was often hazardous and there was a considerable mark-up in prices each time goods exchanged hands. The closer to the source one got, the greater the rewards. 6.1 The Coming of Islam to South-east Asia In as far as South-east Asia is concerned, Arab ships were sailing in Malay and Indonesian waters from the sixth cen- tury onwards. Commerce with China was one reason for their presence there, but perhaps even more of an incentive was the lucrative trade in spices — mainly pepper, cloves and nutmeg — which were obtained from Java, Sumatra and the Moluccas (Maluku) and Banda islands at the eastern end of the archipelago. No doubt the first Arab traders in the region were no more than seasonal visitors, swashbuckling merchant 122 Islam in South-east Asia 123 adventurers who filled their holds with spices and other exotic produce before sailing back with the north-east monsoon to India and the Arabian Peninsula. -

What Every Christian High School Student Should Know About Islam - an Introduction to Islamic History and Theology

WHAT EVERY CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT SHOULD KNOW ABOUT ISLAM - AN INTRODUCTION TO ISLAMIC HISTORY AND THEOLOGY __________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the School of Theology Liberty University __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry __________________ by Bruce K. Forrest May 2010 Copyright © 2010 Bruce K. Forrest All rights reserved. Liberty University has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. APPROVAL SHEET WHAT EVERY CHRISTIAN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT SHOULD KNOW ABOUT ISLAM - AN INTRODUCTION TO ISLAMIC HISTORY AND THEOLOGY Bruce K. Forrest ______________________________________________________ "[Click and enter committee chairman name, 'Supervisor', official title]" ______________________________________________________ "[Click here and type committee member name, official title]" ______________________________________________________ "[Click here and type committee member name, official title]" ______________________________________________________ "[Click here and type committee member name, official title]" Date ______________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to acknowledge all my courageous brothers and sisters in Christ who have come out of the Islamic faith and have shared their knowledge and experiences of Islam with us. The body of Christ is stronger and healthier today because of them. I would like to acknowledge my debt to Ergun Mehmet Caner, Ph.D. who has been an inspiration and an encouragement for this task, without holding him responsible for any of the shortcomings of this effort. I would also like to thank my wife for all she has done to make this task possible. Most of all, I would like to thank the Lord for putting this desire in my heart and then, in His timing, allowing me the opportunity to fulfill it. -

Malaysia and Brunei: an Analysis of Their Claims in the South China Sea J

A CNA Occasional Paper Malaysia and Brunei: An Analysis of their Claims in the South China Sea J. Ashley Roach With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Cleared for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA Foreword This is the second of three legal analyses commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. Policy Options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain J. -

Hukum Kanun Brunei

HUKUM KANUN BRUNEI HUBUNGANNYA DENGAN KONSEP MELAYU ISLAM BERAJA Dr Haji Tassim bin Haji Abu Bakar Pengarah Penolong Profesor Kanan Akademi Pengajian Brunei Universiti Brunei Darussalam ABSTRAK Kertas Kerja ini membincangkan tentang Hukum Kanun Brunei yang mencatatkan mengenai undang – undang Kesultanan Brunei tradisional khususnya sebelum pentadbiran British pada tahun 1906 Masihi. Perbincangan ditumpukan kepada hubungan manuskrip ini dengan konsep Melayu Islam Beraja (MIB) kerana ketiga – tiga komponen berkenaan ditemui dalam manuskrip tersebut. Selain itu, pembicaraan juga menyentuh tentang bukti perlaksanaan undang – undang Islam di Brunei pada abad ke-19 sebagaimana termaktub dalam Hukum Kanun Brunei. Hasil analisis ini memperlihatkan bagaimana Hukum Kanun Brunei bukan sahaja undang-undang dalam kertas tetapi juga diamalkan oleh Kesultanan Brunei dalam menjaga keamanan dan kesejahteraan masyarakat Brunei. Dari amalan ini ternyata kanun ini mampu mendokong dalam memperkasakan konsep MIB dalam menjalani kehidupan berbangsa dan bernegara bagi Kesultanan Brunei zaman berzaman. Pengenalan • Sebelum abad ke-20 Masihi kesultanan-kesultanan di Alam Melayu memang mempunyai undang-undang mereka sendiri yang pada umumnya berteraskan undang-undang Islam di samping undang- undang adat. • Undang–undang ini diwujudkan pada dasarnya untuk menegakkan keadilan yang akan memberi impak kepada keamanan dan kesejahteraan negara. • Kemunculan undang-undang ini boleh ditemui pada Kesultanan Melaka, Pahang, Kedah dan Perak yang masing–masing dikenali sebagai Undang–Undang Melaka, Undang–Undang Pahang, Undang–Undang Kedah dan Undang–Undang Sembilan Puluh Sembilan. Pengenalan • Hal yang sama juga berlaku kepada Kesultanan Brunei tradisional sebelum tahun 1906 apabila pentadbiran Residen British diperkenalkan pada tahun ini. Undang-undang itu dikenali sebagai Hukum Kanun Brunei. • Bagaimanapun, pembentangan ini hanya membincangkan mengenai hubungan Hukum Kanun Brunei dengan falsafah Negara Brunei Darussalam yang berkonsepkan Melayu Islam Beraja (MIB). -

Constructions of the Gambus Hijaz

http://inthegapbetween.free.fr/pierre/PROCESS_PROJECT/process_malay_gambus_hijaz_skin_v10.pdf CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE GAMBUS HIJAZ Version Date On line Updates V0.0 Oct 20 12 yes Creation dHerouville P. V8.0 March 2016 yes About Pak USNI dHerouville P. V9.0 Aug 2016 yes Split from Kalimantan production dHerouville P. V10 Dec. 2016 yes Updates in Riau dHerouville P. The Gambus name nowadays took an unexplicit acception in the indonesian archipelago, since the word became synonymous of “ middle east-like lute” there. If the word is certainly rooted in the Yemeni name The formalization of the Panting-Banjar genre doesn’t date back later than the mid 1970’s, since this “Qanbus”, according to the homonymous lute of the Sana’an plateau, for sure, every current Indonesian genre possibly merged actually various remnant reliefs of former foklores. Actually it used reportedly to avatars now embody various designs. Three main categories of Gambus coexist Malaysia and Indonesia: accompany Gandut dance and Zapin . A former musical forecomer was the Kasenian Bajapin , whose original line up (1973) was 1 Gambus melayu/ Gambus Hadramawt lute, 1 Babun percussion, 1 gong. Violin is 1. - Gambus Hijaz, a monoxyle, long necked lute. Also known there as Gambus Melayu (malay, incl. Kutai reported to have substituted the former Triangle idiophon. Now the usual line up features alternately 2 Gambus tribesmen in south Kalimantan), Panting (Benjmarsin/Banjarmasin, and, actually everywhere in melayu/ Gambus Hadramawt lutes , 1 locally made Cello, or, alternately, 1 rebana viele, 1 marwas –like Kalimantan) , Gita Nangka (Singapore), Gambus Seludang , Gambus Perahu , Gambus Biawak , drum, and some additional mandolinas, or 1 Panting ( a.k.a. -

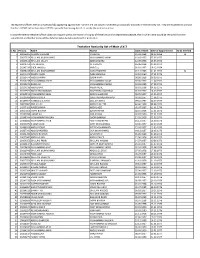

S. No Pers.No. Name Fname Date of Birth Date of Appointment to Be

The teachers/officers with an ampersand (&) appearing against their name in the last column have been provisionally indicated in the seniority list. They are requested to contact the district EMIS cell or the relevant DEO to provide the missing details or rectify the erroneous entry. In case the relevant teacher/officer does not respond within one month of display of these lists on the department website, then his/her name would be removed from the seniority list and his/her name will be deferred when being considered for promotion. Tentative Seniority list of Male J.V.T S. No Pers.no. Name Fname Date of Birth Date of Appointment To be Verified 1 20026395 KHADIM HUSSAIN KAZIM ALI 21.01.1968 08.12.1968 & 2 20027154 GHULAM MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD KHAN 16.10.1957 07.06.1973 3 20027146 GHULAM ULLAH ABDUL RAHIM 12.09.1958 06.03.1974 4 20099751 FIAZ ULLHAQ M. HUSSAN 16.06.1958 01.04.1974 5 20243319 SHER JAN 60yr MIR GUL 01.01.1957 19.12.1974 6 20098249 GHULAM MOHAMMAD KARIM BAKHSH 01.11.1963 01.01.1975 & 7 20294392 ZAHRO KHAN NABI BAKHASH 03.10.1960 17.01.1975 8 20139474 ABDUL KARIM QASIR KHAN 08.08.1958 06.03.1975 9 20156218 MUHAMMAD UMER MUHAMMAD HAYAT 03.04.1957 11.04.1975 10 20242249 BAGH ALI MOHAMMAD KARIM 03.03.1958 27.04.1975 11 20224216 ABDUL BARI. MEER AFZAL. 03.10.1958 04.05.1975 12 20157921 SAKHI MUHAMMAD WAZEER MUHAMMAD 01.10.1957 14.05.1975 13 20160153 MOHAMMAD SHAH ABDUL GHAFOOR 08.05.1957 25.05.1975 14 20210985 ABDUL QADIR QAZI DAD MUHAMMAD 03.03.1957 11.06.1975 15 20185657 NASEEB GUL KHAN GUL JAN KHAN 09.10.1957 22.07.1975 16 20027902 SAIF ULLAH ABDUL HALEEM 04.04.1959 09.09.1975 17 20177483 NASEEB KHAN ABDUL AZIZ 01.07.1957 02.01.1976 18 20027053 IMAM BAKHSH QAISAR KHAN 02.07.1958 11.01.1976 19 20145098 LIAQAT ALI MIR ALI JAN 04.03.1959 27.01.1976 20 20149744 MOHAMMAD HASSAN QADIR BAKHSH 15.01.1958 05.02.1976 21 20100016 MUHAMMAD AYUB HAJI PAIND KHAN 16.12.1957 13.03.1976 22 20027079 SHAIM KHAN. -

From Po-Li to Rajah Brooke: Culture, Power and the Contest for Sarawak

From Po-li to Rajah Brooke: Culture, Power and the Contest for Sarawak John Henry Walker International and Political Studies,University of New South Wales Canberra, Australia *Corresponding author Email address: [email protected]. ABSTRACT This article explores Sarawak’s remoter past from the emergence of an early Indianised state at Santubong until the accession as Rajah of Sarawak of James Brooke. Through an analysis of Sarawak Malay oral histories, the Negara-Kertagama, Selsilah Raja Raja Sambas and the Selsilah Raja RajaBerunai, the article confirms and extends IbLarsens’s findings, that extensive periods of Sambas’s rule over Sarawak has been overlooked by successive scholars. The article also explores the ways in which Malay oral and traditional histories can be used in western historiographic traditions to illuminate the remoter past. Keywords:Indianisation, Sarawak, Sambas, Brunei, DatuMerpati, Sultan Tengah Prior to the expansion of its meaning in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the term ‘Sarawak’ referred to a negri(country) which encompassed the Sarawak and Lundu River basins, and the coast and adjacent islands between the mouths of the Sarawak and Lundu Rivers, an area known in the scholarly literature as ‘Sarawak Proper’, to distinguish it from the more expansive Sarawak which we know today.1 AlthoughSarawak achieved its present boundaries only with the transfer of Lawas from the British North Borneo Company in January 1905,2 it has a long and contested, if intermittently documented, history. In 2012, Ib Larsen suggested that large parts of present day Sarawak had been ruled for significant periods of time by Sambas rather than by Brunei.