The Columbus Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NFS FormlO-MO* OMB Appro** No. 10244018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ___ Page ___ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 96000412 Date Listed: 4/24/96 South Layton Boulevard Historic District, Milwaukee County, WI Property Name County state Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. Signature of the Keeper Date or Action Amended Items in Nomination: The nomination form checks both "district" and "structure" as the category of the property (Section 5) . The correct category is "district." This information was verified with Jim Draeger of the Wisconsin SHPO. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (January 1992) United States Department of Interior RECEIVED 2280 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places MAR I 11996 Registration Form HISTOfilC PLACE This form is for use in nominating or requesting deTe'ffiJUJNPI': fojJj^EfiffithT'incli vidual properties and districts. See instructions in WWW C3 UofipletS T.ne National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. -

Modernism in Bartholomew County, Indiana, from 1942

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MODERNISM IN BARTHOLOMEW COUNTY, INDIANA, FROM 1942 Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form E. STATEMENT OF HISTORIC CONTEXTS INTRODUCTION This National Historic Landmark Theme Study, entitled “Modernism in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Design and Art in Bartholomew County, Indiana from 1942,” is a revision of an earlier study, “Modernism in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Design and Art in Bartholomew County, Indiana, 1942-1999.” The initial documentation was completed in 1999 and endorsed by the Landmarks Committee at its April 2000 meeting. It led to the designation of six Bartholomew County buildings as National Historic Landmarks in 2000 and 2001 First Christian Church (Eliel Saarinen, 1942; NHL, 2001), the Irwin Union Bank and Trust (Eero Saarinen, 1954; NHL, 2000), the Miller House (Eero Saarinen, 1955; NHL, 2000), the Mabel McDowell School (John Carl Warnecke, 1960; NHL, 2001), North Christian Church (Eero Saarinen, 1964; NHL, 2000) and First Baptist Church (Harry Weese, 1965; NHL, 2000). No fewer than ninety-five other built works of architecture or landscape architecture by major American architects in Columbus and greater Bartholomew County were included in the study, plus many renovations and an extensive number of unbuilt projects. In 2007, a request to lengthen the period of significance for the theme study as it specifically relates to the registration requirements for properties, from 1965 to 1973, was accepted by the NHL program and the original study was revised to define a more natural cut-off date with regard to both Modern design trends and the pace of Bartholomew County’s cycles of new construction. -

Discover Historic Wichita! Booklet

KEY: WICHITA REGISTER OF WRHP - HISTORIC PLACES REGISTER OF HISTORIC RHKP - KANSAS PLACES NATIONAL REGISTER OF NRHP - HISTORIC PLACES For more information contact: Historic Preservation Office Metropolitan Area Planning Department 10th Floor-City Hall 455 N. Main Wichita, Kansas 67202 (316) 268-4421 www.wichita.gov ind out more about Wichita’s history on the Discover Historic Wichita! guided F trolley tour. 316-352-4809 INTRODUCTION Discover Historic Wichita was first published in 1997. A second edition was printed in 2002 with a few minor changes. Since that printing, Wichita property owners have expressed a growing interest in listing their properties in the Register of Historic Kansas Places (RHKP) and the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and many have been added. Also, a commercial area, the Warehouse and Jobbers District, was listed in 2003 and Wichita’s four historic districts were listed in the RHKP and NRHP in 2004. In this latest edition additional research was conduct- ed to ensure accuracy. The brochure is organized alphabetically by the name of the structure. The entries are also numbered to correspond with locations on the map found at the front of the brochure. An online publication of the Discover Historic Wichita brochure is updated as properties and/or his- toric districts are added to Wichita’s inventory of list- ed properties. The current version is on the Historic Preservation Office website at http://www.wichita. gov/Residents/History/. Biographical notes of relevant architects have been added to this brochure. Wichita’s periods of economic boom and bust brought these professionals to town to take advantage of building surges. -

LCF-Annualreport.Pdf

UTK Tower: Marshall Prado, 2018–19 UDRF Fellow Executive Summary The Columbus, Indiana community continues to demonstrate that the best way to have an authentically great place to live is through the process of working together with shared values and clear goals. Engaging excellent designers and relying upon a thoughtful process to build new buildings, landscapes, artworks, or reuse existing ones is a key part of our history. After more than seventy-five years, this tradition has created what we hold dear today: an internationally-recognized collection of architecture, art, and design that has become a defining characteristic of the community and the core of this city’s identity. Heritage Fund — The Community Foundation of Bartholomew County launched Landmark Columbus Foundation (LCF) in 2015 as one of its key programs to ensure that Columbus’ traditions and investments in design excellence are well cared for and can remain a source of inspiration for future generations. With the support of many in this community and those around the state and country, Heritage Fund’s program quickly became a community asset making a big difference through Exhibit Columbus and many progressive preservation efforts. 1 Executive Summary Bartholomew County Courthouse: Isaac Hodgson, 1874 In late 2019 Heritage Fund supported the move of this program to become a stand alone 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, with the mission to care for, celebrate, and advance the cultural heritage of Columbus, Indiana. At the start of 2020, the inaugural Board of Directors of LCF met to move the mission forward, and with dedicated staff, volunteers, and collaborators, this organization has made great progress and is poised for continued success far beyond today. -

Cataloging Architecture and Architectural Drawings with CDWA, CCO, and the GETTY VOCABULARIES

8/24/2018 Cataloging Architecture and Architectural Drawings WITH CDWA, CCO, AND THE GETTY VOCABULARIES Patricia Harpring Managing Editor, Getty Vocabulary Program Revised 27 August 2018 © J. Paul Getty Trust, author: Patricia Harpring. August 2018 For educational purposes only. Do not distribute. Image credits: see final slide CATALOGING ARCHITECTURE AND ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS Author: Patricia Harpring , copyright J. Paul Getty Trust For educational purposes Images may be under additional copyright revised August 2018 1 8/24/2018 Table of Contents • Which Standards to Use ..... 3 • Materials and Techniques, Dimensions ... 126 • General Information about Cataloging .... 17 • Depicted Subject ...... 143 • AAT, TGN, ULAN, CONA, IA .... 44 • Inscriptions, Watermarks, etc. .... 159 • Relationships: Equivalence, Hierarchical, • Events ...... 165 Associative .... 60 • Style and Culture .... 168 • Catalog Level, Classification, Work Type .... 77 • Descriptive Note .... 171 • Title / Name ..... 93 • Provenance and Copyright ... 175 • Creator, Related People ..... 98 • Edition and State ..... 178 • Creation Date, Other Dates .... 111 • Other Important Data .... 181 • Current Location, Other Locations .... 120 • Making Data Accessible, Getty vocabs. .... 192 © J. Paul Getty Trust, author: Patricia Harpring. August 2018 For educational purposes only. Do not distribute. CATALOGING ARCHITECTURE AND ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS Author: Patricia Harpring , copyright J. Paul Getty Trust For educational purposes Images may be under additional copyright revised August 2018 2 8/24/2018 Which Standards to Use? CDWA, CCO, others © J. Paul Getty Trust, author: Patricia Harpring. August 2018 For educational purposes only. Do not distribute. CATALOGING ARCHITECTURE AND ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS Author: Patricia Harpring , copyright J. Paul Getty Trust For educational purposes Images may be under additional copyright revised August 2018 3 8/24/2018 What Standards and Vocabularies to Use? • Why use standards and controlled vocabularies? To build good data. -

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth Cover image: Installation View, Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010–11, 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Henry Moore’s Public Sculpture in the US: The Collaborations with I. -

STUDY REPORT Milwaukee Journal Building Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Building MARCH, 2019

PERMANENT HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT Milwaukee Journal Building Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Building MARCH, 2019 I. NAME Historic: Milwaukee Journal Building Common Name: Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Building II. LOCATION 333 West State Street Legal Description Tax Key No. 3610559111 ORIGINAL PLAT OF MILWAUKEE W OF THE RIVER IN SE ¼ OF SEC 20-7-22 BLOCK 51 & ALL VAC ALLEYS EXC W 132’ OF LOT 15 BID # 15, #21; TID #84 III. CLASSIFICATION Site IV. OWNER Journal Sentinel Inc. c/o/Gannett Tax Dep 7950 Jones Branch Drive McLean, VA 221023302 rd ALDERMAN Ald. Robert Bauman 4 Aldermanic District NOMINATOR Ald. Robert Bauman and Ald. Michael Murphy V. YEAR BUILT 1924 (Milwaukee Building Permits January 10, 1924) ARCHITECT: Frank D. Chase, Inc. (Milwaukee Building Permits January 10, 1924; The American Architect, November 20, 1924) NOTE: This nomination was submitted by Alderman Murphy and Alderman Bauman due to the uncertain future of the property. The current owner is looking for a new location in the city and has placed the property up for sale. Also, there may be a change in corporate ownership which can impact the sale of the property and subsequent future of the site. VI. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION THE AREA The Milwaukee Journal Building is located west of the Milwaukee River in Milwaukee’s Central Business District. To the north is Old World Third Street which is both locally designated and National Register listed. This portion of the downtown is comprised of 19th century masonry commercial buildings that stand two through five stories tall. To the west and northwest are large scale buildings devoted to sports and entertainment: the Arena, the Auditorium (now Milwaukee Theater), the Bradley Center (in the process of being demolished during the winter 1 of 2018 – 2019), and the Fiserv Forum (Bucks arena) (completed 2018). -

125-127 & 125-1/2 Third Street 125-127 Third Street

125-127 & 125-1/2 Third Street 125-127 Third Street Wild/Clavadatscher-Witwen Block Located on the north side of Third Street between Oak and Ash Streets. Block 26, lot 9 Sanborn map location 206 Third Street Architectural Description Unfortunately, this building has undergone a great deal of transformation. The pressed metal cornice, unique in Baraboo as it carried in relief images of household goods (i.e. lamps, kettles, pitchers, etc.), has been removed and replaced with sheets of metal. Four segmented-arched windows have been removed and the openings covered. Still extant as of this writing are four corresponding window hoods, as well as simple brickwork beneath the roofline. The original storefront has been removed and replaced with contemporary materials, the lines of which do not correspond to the original plan. Despite alterations, the building is considered a contributing element of an intact blockface. L-R Settergren & Pittman Hardware, J. P. Witwen Real Estate & In December of 1874, J. B. Tinkelpaugh had a Restaurant at Insurance, C. H. Farnum Garage approximately this address, advertising Oysters by the quart at fifty- cents. In January of 1875, Tinkelpaugh sold his restaurant to Messrs. house their new establishment known as The Fair. Prior to becoming D. N. Nickerson and Samuel Steele. associated with Clavadatscher, Witwen was Sauk County’s efficient In March of 1886, the frame building located at this site and clerk. The company moved here from a building that was located at owned by Louis Wild was destroyed by fire. The Millinery Store of approximately 115 Third Avenue. An interesting amenity in their new Mrs. -

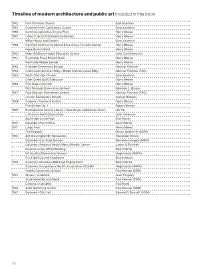

Timeline of Modern Architecture and Public Art Included in This Book

Timeline of modern architecture and public art included in this book 1942 First Christian Church Eliel Saarinen 1954 Cummins Irwin Conference Center Eero Saarinen 1955 Cummins Columbus Engine Plant Harry Weese 1957 Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School Harry Weese Miller House and Garden Eero Saarinen 1958 Hamilton Community Center & Ice Arena / Lincoln Center Harry Weese Hope Branch Bank Harry Weese 1960 Mabel McDowell Adult Education Center John Carl Warnecke 1961 Eastbrook Plaza Branch Bank Harry Weese Northside Middle School Harry Weese 1962 Parkside Elementary School Norman Fletcher 1963 Information Services Bldg. / BCSC Administrative Bldg. Norman Fletcher (TAC) 1964 North Christian Church Eero Saarinen Otter Creek Golf Clubhouse Harry Weese 1965 First Baptist Church Harry Weese W.D. Richards Elementary School Edwards L. Barnes 1967 Four Seasons Retirement Center Norman Fletcher (TAC) Lincoln Elementary School Gunnar Birkerts 1968 Cummins Technical Center Harry Weese Fire Station No. 4 Robert Venturi 1969 Bartholomew County Library / Cleo Rogers Memorial Library I.M. Pei L. Frances Smith Elementary John Johansen Southside Junior High Eliot Noyes 1970 Columbus Post Office Kevin Roche 1971 Large Arch Henry Moore The Republic Myron Goldsmith (SOM) 1972 301 Washington St. Renovation Alexander Girard Columbus East High School Romaldo Giurgola (MGA) Columbus Regional Health Mental Health Center James S. Polshek Cummins Irwin Office Building Kevin Roche Mt. Healthy Elementary School Hugh Hardy (HHPA) Par 3 Golf Course Clubhouse Bruce Adams 1973 Cummins Columbus Midrange Engine Plant Kevin Roche Cummins Occupational Health Association (COHA) Hugh Hardy (HHPA) Fodrea Community School Paul Kennon (CRS) 1974 Chaos I, sculpture Jean Tinguley State Street Branch Bank Paul Kennon (CRS) Dancing Cs graphic Paul Rand 1978 AT&T Switching Center Paul Kennon (CRS) 1981 Columbus City Hall Edward C. -

The History of Large Federal Dams: Planning, Design, and Construction in the Era of Big Dams

THE HISTORY OF LARGE FEDERAL DAMS: PLANNING, DESIGN, AND CONSTRUCTION IN THE ERA OF BIG DAMS David P. Billington Donald C. Jackson Martin V. Melosi U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Denver Colorado 2005 INTRODUCTION The history of federal involvement in dam construction goes back at least to the 1820s, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built wing dams to improve navigation on the Ohio River. The work expanded after the Civil War, when Congress authorized the Corps to build storage dams on the upper Mississippi River and regulatory dams to aid navigation on the Ohio River. In 1902, when Congress established the Bureau of Reclamation (then called the “Reclamation Service”), the role of the federal government increased dramati- cally. Subsequently, large Bureau of Reclamation dams dotted the Western land- scape. Together, Reclamation and the Corps have built the vast majority of ma- jor federal dams in the United States. These dams serve a wide variety of pur- poses. Historically, Bureau of Reclamation dams primarily served water storage and delivery requirements, while U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dams supported QDYLJDWLRQDQGÀRRGFRQWURO)RUERWKDJHQFLHVK\GURSRZHUSURGXFWLRQKDVEH- come an important secondary function. This history explores the story of federal contributions to dam planning, design, and construction by carefully selecting those dams and river systems that seem particularly critical to the story. Written by three distinguished historians, the history will interest engineers, historians, cultural resource planners, water re- source planners and others interested in the challenges facing dam builders. At the same time, the history also addresses some of the negative environmental consequences of dam-building, a series of problems that today both Reclamation and the U.S. -

Schedule of Events

Exhibit Columbus / DOCOMOMO-US / AIA Indiana & AIA Kentucky / Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields (Design & Decorative Arts Department) REGISTER SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Wednesday 26 September The symposium begins in Indianapolis at Newfields. Join us for exclusive tours of the newly reinstalled design galleries at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, as well as the first reception and Evening Conversation of the symposium. All events on Wednesday take place in Indianapolis at the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. 2:00-5:00 pm – Afternoon Tours at Newfields Design Gallery Tour 1 AIA LU|HSW The Indianapolis Museum of Art’s 11,000-square-foot Design Gallery is the largest collection gallery devoted to modern and contemporary design of any museum in the country. Join Shelley Selim, Associate Curator of Design and Decorative Arts, for a tour of the recently renovated gallery, now featuring a thematic reinterpretation that offers fresh insights into the versatile design process—from inspiration to production. A rotation of more than 150 new objects will be on display, many of which are recent acquisitions being shown for the first time. Newfields’ famed Miller House and Garden assumes a greater presence in the gallery with a fully immersive virtual reality experience. This joins several other new interactive spaces, including an 800-square-foot Design Lab where guests can design prototypes using analog and digital tools and try out some of the furniture on display. Participants will: Illustrate how the building meets certain universal design requirements for art museums. Observe the outcome of design strategies that were specific to the recent gallery renovation. -

Exhibit Columbus: Context, Precedent, and Prototype

Exhibit Columbus: Context, Precedent, and Prototype JOSHUA COGGESHALL Ball State University JANICE SHIMIZU Ball State University How can an architectural exhibition speak to ideas Lasch, Plan B Architecture & Urbanism, Oyler Wu Collaborative, of between-ness? How can a temporal event for- studio:indigenous, and IKD. ever transform the understanding of a place? In - Washington Street installations: Five international design gal- 2014, along with a small talented team, we started leries commissioned designers to add interventions that would working on a project with the goal to transform and connect emerging trends in design to the commercial core- Studio heighten awareness of the architectural legacy of Formafantasma, Pettersen & Hein, Productora, Cody Hoyt, and Columbus, Indiana, through the production of con- Snarkitecture temporary architecture and design. In this paper, we - University Installations: Six Midwest universities built prototypes will describe Exhibit Columbus’ curatorial premises beside Central Middle School and North Christian church- Ball State of dialogue and context through the lens of our mul- University, College of Architecture and Planning; The Ohio State tiple roles: as members of the steering committee University, Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture; University of that defined its curatorial vision, as university instal- Cincinnati, School of Architecture and Interior Design; University of lation coordinators who hope to impact architecture Kentucky, College of Design, School of Architecture; University of Michigan, Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, education in the Midwest, faculty research, and thoughts on pedagogy, and finally as instructor for - High School Installations: Local students did a design-build at the a design-build studio. historic post office.