Earl Hall Multiple Property: No Other Names/Site Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968

THE POLITICS OF SPACE: STUDENT COMMUNES, POLITICAL COUNTERCULTURE, AND THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PROTEST OF 1968 Blake Slonecker A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Peter Filene Reader: Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Reader: Jerma Jackson © 2006 Blake Slonecker ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT BLAKE SLONECKER: The Politics of Space: Student Communes, Political Counterculture, and the Columbia University Protest of 1968 (Under the direction of Peter Filene) This thesis examines the Columbia University protest of April 1968 through the lens of space. It concludes that the student communes established in occupied campus buildings were free spaces that facilitated the protestors’ reconciliation of political and social difference, and introduced Columbia students to the practical possibilities of democratic participation and student autonomy. This thesis begins by analyzing the roots of the disparate organizations and issues involved in the protest, including SDS, SAS, and the Columbia School of Architecture. Next it argues that the practice of participatory democracy and maintenance of student autonomy within the political counterculture of the communes awakened new political sensibilities among Columbia students. Finally, this thesis illustrates the simultaneous growth and factionalization of the protest community following the police raid on the communes and argues that these developments support the overall claim that the free space of the communes was of fundamental importance to the protest. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Peter Filene planted the seed of an idea that eventually turned into this thesis during the sort of meeting that has come to define his role as my advisor—I came to him with vast and vague ideas that he helped sharpen into a manageable project. -

Download This Issue As A

MICHAEL GERRARD ‘72 COLLEGE HONORS FIVE IS THE GURU OF DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI CLIMATE CHANGE LAW WITH JOHN JAY AWARDS Page 26 Page 18 Columbia College May/June 2011 TODAY Nobel Prize-winner Martin Chalfie works with College students in his laboratory. APassion for Science Members of the College’s science community discuss their groundbreaking research ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 26 20 30 18 73 16 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 2 20 A PA SSION FOR SCIENCE 38 B OOKSHELF LETTERS TO THE Members of the College’s scientific community share Featured: N.C. Christopher EDITOR Couch ’76 takes a serious look their groundbreaking work; also, a look at “Frontiers at The Joker and his creator in 3 WITHIN THE FA MILY of Science,” the Core’s newest component. Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of By Ethan Rouen ’04J, ’11 Business Comics. 4 AROUND THE QU A DS 4 Reunion, Dean’s FEATURES 40 O BITU A RIES Day 2011 6 Class Day, 43 C L A SS NOTES JOHN JA Y AW A RDS DINNER FETES FIVE Commencement 2011 18 The College honored five alumni for their distinguished A LUMNI PROFILES 8 Senate Votes on ROTC professional achievements at a gala dinner in March. -

1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster. Hope College

Hope College Digital Commons @ Hope College Hope College Catalogs Hope College Publications 1961 1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster. Hope College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/catalogs Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Hope College, "1961-1962. Bulletin and College Roster." (1961). Hope College Catalogs. 130. http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/catalogs/130 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Hope College Publications at Digital Commons @ Hope College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hope College Catalogs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Hope College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOPE COLLEGE BULLETIN COLLEGE ROSTER TABLE OF CONTENTS C O L L E G E R O S T E R page The College Staff - Fall 1961 2 Administration 2 Faculty 4 The Student Body - Fall 1961 7 Seniors 7 Juniors 9 Sophomores 12 Freshmen 16 Special Students 19 Summer School Students - Fall 1961 21 Hope College Campus 21 Vienna Campus 23 COLLEGE DIRECTORY Fall 1961 (Home and college address and phone numbers) The College Staff 25 Students 29 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Library Information 58 Health Service 59 College Residences 60 College Telephones 61 NEW STAFF MEMBERS-SECOND SEMESTER Name Home Address College Address Phone Coates, Mary 110 E. 10th St. Durfee Hall EX 6-7822 Drew, Charles 50 E. Central Ave., Zeeland P R 2-2938 Fried, Paul 18 W. 12th St. Van Raalte 308 E X 6-5546 Loveless, Barbara 187 E. 35th St. E X 6-5448 Miller, James 1185 E. -

Barnard College Bulletin 2017-18 3

English .................................................................................... 201 TABLE OF CONTENTS Environmental Biology ........................................................... 221 Barnard College ........................................................................................ 2 Environmental Science .......................................................... 226 Message from the President ............................................................ 2 European Studies ................................................................... 234 The College ........................................................................................ 2 Film Studies ........................................................................... 238 Admissions ........................................................................................ 4 First-Year Writing ................................................................... 242 Financial Information ........................................................................ 6 First-Year Seminar ................................................................. 244 Financial Aid ...................................................................................... 6 French ..................................................................................... 253 Academic Policies & Procedures ..................................................... 6 German ................................................................................... 259 Enrollment Confirmation ........................................................... -

Student Life the Arts

Student Life The Arts University Art Collection the steps of Low Memorial Library; Three- “Classical Music Suite,” the “Essential Key- Way Piece: Points by Henry Moore, on board Series,” and the “Sonic Boom Festival.” Columbia maintains a large collection of Revson Plaza, near the Law School; Artists appearing at Miller Theatre have art, much of which is on view throughout Bellerophon Taming Pegasus by Jacques included the Juilliard, Guarneri, Shanghai, the campus in libraries, lounges, offices, Lipchitz, on the facade of the Law School; a Emerson, Australian, and St. Petersburg and outdoors. The collection includes a cast of Auguste Rodin’s Thinker, on the String Quartets; pianists Russell Sherman, variety of works, such as paintings, sculp- lawn of Philosophy Hall; The Great God Peter Serkin, Ursula Oppens, and Charles tures, prints, drawings, photographs, and Pan by George Grey Barnard, on the lawn Rosen; as well as musical artists Joel Krosnick decorative arts. The objects range in date of Lewisohn Hall; Thomas Jefferson, in front and Gilbert Kalish, Dawn Upshaw, Benita from the ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals of the Journalism Building, and Alexander Valente, Speculum Musicae, the Da Capo of the second millennium B.C.E. to con- Hamilton, in front of Hamilton Hall, both Chamber Players, Continuum, and the temporary prints and photographs. by William Ordway Partridge; and Clement New York New Music Ensemble. Also in the collection are numerous por- Meadmore’s Curl, in front of Uris Hall. The “Jazz! in Miller Theatre” series has help- traits of former faculty and other members ed to preserve one of America’s most important of the University community. -

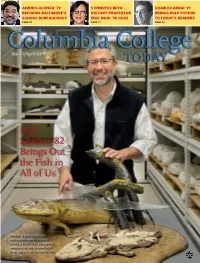

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Peter F. Andrews Sportswriting and Broadcasting Resume [email protected] | Twitter: @Pfandrews | Pfandrews.Wordpress.Com

Peter F. Andrews Sportswriting and Broadcasting Resume [email protected] | Twitter: @pfandrews | pfandrews.wordpress.com RELEVANT EXPERIENCE Philly Soccer Page Staff Writer & Columnist, 2014-present: Published over 100 posts, including match reports, game analysis, commentary, and news recaps, about the Philadelphia Union and U.S. National Teams. Covered MLS matches, World Cup qualifiers, Copa America Centenario matches, and an MLS All-Star Game at eight different venues across the United States and Canada. Coordinated the launch of PSP’s Patreon campaign, which helps finance the site. Appeared as a guest on one episode of KYW Radio’s “The Philly Soccer Show.” Basketball Court Podcast Host & Producer, 2016-present: Produced a semi-regular podcast exploring the “what-ifs” in the history of the National Basketball Association, presented in a humorous faux-courtroom style. Hosted alongside Sam Tydings and Miles Johnson. Guests on the podcast include writers for SBNation and SLAM Magazine. On The Vine Podcast Host & Producer, 2014-present: Produced a weekly live podcast on Mixlr during the Ivy League basketball season with writers from Ivy Hoops Online and other sites covering the league. Co-hosted with IHO editor-in- chief Michael Tony. Featured over 30 guests in three seasons. Columbia Daily Spectator Sports Columnist, Fall 2012-Spring 2014: Wrote a bi-weekly column for Columbia’s student newspaper analyzing and providing personal reflections on Columbia’s athletic teams and what it means to be a sports fan. Spectrum Blogger, Fall 2013: Wrote a series of blog posts (“All-22”) which analyzed specific plays from Columbia football games to help the average Columbia student better understand football. -

Physical Education and Athletics at Horace Mann, Where the Life of the Mind Is Strengthened by the Significance of Sports

magazine Athletics AT HORACE MANN SCHOOL Where the Life of the Mind is strengthened by the significance of sports Volume 4 Number 2 FALL 2008 HORACE MANN HORACE Horace Mann alumni have opportunities to become active with their School and its students in many ways. Last year alumni took part in life on campus as speakers and participants in such dynamic programs as HM’s annual Book Day and Women’s Issues Dinner, as volunteers at the School’s Service Learning Day, as exhibitors in an alumni photography show, and in alumni athletic events and Theater For information about these and other events Department productions. at Horace Mann, or about how to assist and support your School, and participate in Alumni also support Horace Mann as participants in HM’s Annual Fund planning events, please contact: campaign, and through the Alumni Council Annual Spring Benefit. This year alumni are invited to participate in the Women’s Issues Dinner Kristen Worrell, on April 1, 2009 and Book Day, on April 2, 2009. Book Day is a day that Assistant Director of Development, engages the entire Upper Division in reading and discussing one literary Alumni Relations and Special Events work. This year’s selection is Ragtime. The author, E.L. Doctorow, will be the (718) 432-4106 or keynote speaker. [email protected] Upcoming Events November December January February March April May June 5 1 3 Upper Division Women’s HM Alumni Band Concert Issues Dinner Council Annual Spring Benefit 6-7 10 6 2 6 5-7 Middle Robert Buzzell Upper Division Book Day, Bellet HM Theater Division Memorial Orchestra featuring Teaching Alumni Theater Games Concert E.L. -

1946-Resumes-After-L

Columbia Spectator VOL. LXIX - No. 29. TUESDAY, MARCH 5, 1946. PRICE: FIVE CENTS Success is New SA Head Approved CSPA Draws Petitions Due Thursday Churchill at By Emergency Council School For NROTC Elections 'Club '49; Frank E. Karelsen Ill's resig- High Petitions of candidates for Columbia nation as Chairman of the Stu- Navy representative on the Emergency Council due by dent Administrative Executive Journalists are Expectation noon Thursday, it was announced March 18 election of Frank Council and the 2800 Editors Attend by Fred Kleeberg, chairman of College Kings, Broadway laquinta as his successor were the Elections Commission. Pe- Wartime British Leader confirmed by the Emergency Scholastic Press Group titions may be handed in at the Stars at Hop Saturday; Council last Thursday. Karelsen, King's Crown Office, 405 John To Receive Honorary Invited two term SAAC Chairman, ex- Gathering 21-23 March Jay Hall, or may be handed to Degree at Low Library All Undergrads plained that his decision to re- Kleeberg personally. sign had resulted from his On March 21, 22, and 23, some Plans for one of the most novel Actual elections will take place Winston Churchill, war-tim e "pressing duties" as a newly 2,800 school editors and advisors, and original of social affairs ever on Monday, March 11, in leader of the British people, will elected Emergency Council mem- be presented at Columbia been representing schools from all parts Hartley lobby from noon to one. visit Columbia University on Mon- to ber. However, he expressed con- completed, it was revealed, last of the country, will gather at Col- An officer of the battalion of- day afternoon, March 18, to re- fidence in laquinta who had night by the committee in charge umbia to attend the 22nd annual fice staff will be preent at the ceive from Dr. -

Exploring Cool New Worlds Beyond Our Solar System

WINTER 2017-18 COLUMBIA MAGAZINE COLUMBIA COLUMBIAMAGAZINE WINTER 2017-18 Exploring cool new worlds beyond our solar system 4.17_Cover_FINAL.indd 1 11/13/17 12:42 PM JOIN THE CLUB Since 1901, the Columbia University Club of New York has been a social, intellectual, cultural, recreational, and professional center of activity for alumni of the eighteen schools and divisions of Columbia University, Barnard College, Teachers College, and affiliate schools. ENGAGE IN THE LEGACY OF ALUMNI FELLOWSHIP BECOME A MEMBER TODAY DAVE WHEELER DAVE www.columbiaclub.org Columbia4.17_Contents_FINAL.indd Mag_Nov_2017_final.indd 1 1 11/15/1711/2/17 12:463:13 PM PM WINTER 2017-18 PAGE 28 CONTENTS FEATURES 14 BRAVE NEW WORLDS By Bill Retherford ’14JRN Columbia astronomers are going beyond our solar system to understand exoplanets, fi nd exomoons, and explore all sorts of surreal estate 22 NURSES FIRST By Paul Hond How three women in New York are improving health care in Liberia with one simple but e ective strategy 28 JOIN THE CLUB LETTER HEAD By Paul Hond Scrabble prodigy Mack Meller Since 1901, the Columbia University Club of minds his Ps and Qs, catches a few Zs, and is never at a loss for words New York has been a social, intellectual, cultural, recreational, and professional center of activity for 32 CONFESSIONS alumni of the eighteen schools and divisions of OF A RELUCTANT REVOLUTIONARY Columbia University, Barnard College, By Phillip Lopate ’64CC Teachers College, and affiliate schools. During the campus protests of 1968, the author joined an alumni group supporting the student radicals ENGAGE IN THE LEGACY OF ALUMNI FELLOWSHIP 38 FARSIGHTED FORECASTS By David J. -

Chronology of Events

CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ll quotes are from Spectator, Columbia’s student-run newspaper, unless otherwise specifed. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia A .edu/. Some details that follow are from Up Against the Ivy Wall, edited by Jerry Avorn et al. (New York: Atheneum, 1969). SEPTEMBER 1966 “After a delay of nearly seven years, the new Columbia Community Gymnasium in Morningside Park is due to become a reality. Ground- breaking ceremonies for the $9 million edifice will be held early next month.” Two weeks later it is reported that there is a delay “until early 1967.” OCTOBER 1966 Tenants in a Columbia-owned residence organize “to protest living condi- tions in the building.” One resident “charged yesterday that there had been no hot water and no steam ‘for some weeks.’ She said, too, that Columbia had ofered tenants $50 to $75 to relocate.” A new student magazine—“a forum for the war on Vietnam”—is pub- lished. Te frst issue of Gadfy, edited by Paul Rockwell, “will concentrate on the convictions of three servicemen who refused to go to Vietnam.” This content downloaded from 129.236.209.133 on Tue, 10 Apr 2018 20:25:33 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms LII CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS Te Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) orga- nizes a series of workshops “to analyze and change the social injustices which it feels exist in American society,” while the Independent Commit- tee on Vietnam, another student group, votes “to expand and intensify its dissent against the war in Vietnam.” A collection of Columbia faculty, led by Professor Immanuel Wallerstein, form the Faculty Civil Rights Group “to study the prospects for the advancement of civil rights in the nation in the coming years.” NOVEMBER 1966 Columbia Chaplain John Cannon and ffeen undergraduates, including Ted Kaptchuk, embark upon a three-day fast in protest against the war in Vietnam. -

June 2011 Jewish News

Shabbat & Holiday Candle Lighting Times Allocations Decisions Diffi cult, Friday, June 3 8:08pm Overseas Percentage Increased Tuesday, June 7 8:10pm The Savannah Jewish Federation’s song kept playing through my mind. Wednesday, June 8 8:11pm Allocation Committee is a committee “In this world of ordinary people, Friday, June 10 8:12pm of about 20 individuals, balanced from extraordinary people, I’m glad there across synagogues and organizations is you.” Finding songs to fi t events is “The Allocations committee Friday, June 17 8:14pm and represents various interests and not unusual for me, but these words did a fabulous job making the Friday, June 24 8:16pm perspectives of the community. Dur- seemed to be set on replay, just like ing these still challenging economic Johnny Mathis was at my house when hard decisions. I applaud them” Friday, July 1 8:17pm times and a period of changes in our I was a teenager. Friday, July 8 8:16pm Jewish community, raising the dollars Each person at the meeting was, ination? Yes! Friday, July 15 8:14pm and deciding how to allocate them was to me, extraordinary. No one missed Instead, I believe that we all diffi cult. one of the three meetings. No one left were searching for ways to make next Sitting on the Allocations Commit- early. As a teacher, used to looking at year’s campaign more successful. Nat- In This Issue tee for many meant having to put per- a group and seeing who is and who is urally, all of us hope that the general Shaliach’s message, p2 sonal loyalties to the side and focus on not engaged in the discussion, I knew economy improves for more reasons Letter to the Editor, p2 what is best for our Savannah Jewish that every single person was paying than the Federation campaign.