Old Man of the Mountains by Harold Gilliam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Whitney Via the East Face Trip Notes

Mount Whitney via The East Face Trip Notes 2.18 Mount Whitney via the East Face This is the classic route up the highest peak in the lower forty eight states. The 2000 foot-high face was first as- cended by the powerful team of Robert Underhill, Norman Clyde, Jules Eichorn and Glen Dawson on August 16, 1931. These were the finest climbers of the time; their ascent time of three and a quarter hours is rarely equalled by modern climbers with their tight rock shoes and the latest in climbing hardware. Dawson returned to make the sec- ond ascent of the route and in 1934 Eichorn pioneered the airy Tower Traverse that all current day climbers utilize. Clyde became legendary in the Sierra for both his unequaled number of Sierra first ascents and the size of the packs he carried. Underhill later remarked that on the approach to the East Face Clyde’s pack was “an especially pictur- esque enormity of skyscraper architecture.” Times have changed but the East Face remains a great climb. While only rated 5.6 do not underestimate it! You will be at over 14,000 feet carrying a small pack with the essentials for the day, and ascending about 12 pitches of continuous climbing. Itinerary Day One: The Approach. Starting at the 8,640 foot Whitney Portal we hike Whitney Trail for less than a mile before heading up the steep North Fork of Lone Pine Creek. The trail here is non-maintained and rough with creek crossings and rocks to scramble up and over. -

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Norman Clyde: Legendary Mountain Man E Was a Loner, Totally at Home Thet Scales at Only 140 Pounds, Clyde’S in the Mountains’ Solitude

Friends of the Oviatt Library Spring/Summer 2011 One-of-a-kind Exhibition: Tony Gardner’s Swan Song ome came replace the original Sto view the materials, the sort Library’s rarely of thing that makes seen treasures. up a library’s Special Others came to hear Collections. the keynote speaker, Following Stephen Tabor of Tabor’s thought- the Huntington provoking com Library. But many ments the as long-time friends sembled dignitaries of the library, those and Library friends truly in the know, repaired to the came to honor the Tseng Family Gal Oviatt Library’s lery where, while multi-talented, long- savoring an enticing serving Curator of medley of crudi Special Collections, tés, they ogled an Tony Gardner, who eclectic assortment recently announced his retirement, era of printing, he noted, when er of unique, rare, one-of-a-kind and to ogle his latest, and perhaps rors were found or changes judged ephemera plus portions of some his last, creation for the Library— necessary, presses were stopped, of the Library’s smaller collections. an exhibit featuring unique gems changes were made, and printing Among the items Gardner opted to from the Library’s archives. But for resumed. But the error-bearing showcase in his ultimate exhibition whatever reason, they came; and pages were not discarded—paper were such singular treasures as: A none left disappointed. was much too precious for such hand-written, eyewitness account Tabor, Curator of Early Printed extravagance—and the result was of the 1881 gunfight between the Books at the Huntington, pro books, even from the same print Earps and Clantons at the OK vided an appropriate prelude for ing that differed in subtle ways. -

Wtc 1803C.Pdf

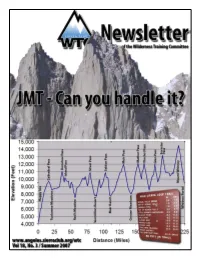

WTC Officers WTC Says Congratulations! By Kay Novotny See page 8 for contact info WTC Chair Scott Nelson Long Beach Area Chair KC Reid Area Vice Chair Dave Meltzer Area Trips Mike Adams Area Registrar Jean Konnoff WTC would like to congratulate 2 of their Orange County leaders on their recognition at the annual Area Chair Sierra Club Angeles Chapter Awards Edd Ruskowitz Banquet. This event took place on May 6th, 2007, Area Vice Chair at the Brookside Country Club in Pasadena. Barry John Cyran Holchin, right, who is an “M”rated leader, and who WTC Outings Chair and Area Trips divided his time last year between Long Tom McDonnell Beach/South Bay’s WTC groups 2 and 3, received a Area Registrar conservation service award. These awards are given Kirt Smoot to Sierra Club members who deserve special San Gabriel Valley recognition for noteworthy service they have ren- Area Chair dered to the Angeles Chapter. Dawn Burkhardt Bob Beach, left, another “M” rated leader, who is Area Vice Chair Shannon Wexler Long Beach/South Bay’s Group 1 assistant leader, Area Trips received the prestigious Chester Versteeg Outings Helen Qian Plaque, which is the highest outings leadership Area Registrar award conferred by the Angeles Chapter. It is James Martens awarded to a Sierra Club member who has pro- vided long-term and outstanding leadership in furthering the enjoyment and safety of the outings program. West Los Angeles Congratulations, Barry and Bob! We all appreciate your hard work and dedication to the WTC program. Area Chair Gerard Lewis Area Vice Chair Kathy Rich Area Trips Graduations Marc Hertz Area Registrar Graduations are currently scheduled for October 20 and 21 at Indian Cove in Joshua Tree National Park. -

Sierra Club Oral History Project SIERRA CLUB REMINISCENCES Francis P. Farquhar Sierra Club Mountaineer and Editor Joel Hi Ldebra

Sierra Club Oral History Project SIERRA CLUB REMINISCENCES Francis P. Farquhar Sierra Club Mountaineer and Editor Joel Hi ldebrand Sierra Club Leader and Ski Mountaineer Bestor Robinson Thoughts on Conservation and the Sierra Club .. .. James E. Rother The Sierra Club in the Early 1900s Interviews Conducted By Ann and Ray Lage Susan Schrepfer Sierra Club Hi story Commi ttee Francis P. Farquhar SIERRA CLUB MOUNTAINEER AND EDITOR An Interview Conducted by Ann and Ray Lage Sierra Club History Commit tee San Francisco, California Sierra Club San Francisco, California copyright@1974 by Sierra Club All rights reserved PREFACE Francis Peloubet Farquhar, honorary president of the Sierra Club, is clearly its most distinguished member in modern times. He started early, of course, just as he did on the first ascent of the Middle Palisade. Born in Newton, Massachusetts, on New Year's Eve of 1888, he graduated from Harvard in 1909 and joined the Sierra Club in California only two years later. That first summer on the High Trip, and later, he learned much of the lore of the-sierra from such leaders as John Muir, Will Colby, and Little Joe LeConte. California and its great natural resources fascinated Francis so much that he delved so deeply into its history that he became a high authority, and later president-of the California ~istoricalsociety. His books, of great interest to club members, included Place Names of the High Sierra (1919-26) ,,L& and Down California ---in1860-1864, -The Journal of wlllir~. Brewer (1930), History --of the Sierra Nevada (196F), and many more. With his immense knowledge of the Sierra and the club, Francis was an excellent editor of the Sierra Club Bulletin for twenty years. -

2021 Publishing

2021 Publishing WHOLESALE CATALOG Yosemite Conservancy inspires people to support projects and programs that preserve Yosemite National Park and enrich the visitor experience. Thanks to generous donors, the Conservancy has provided $119 million in grants to the park to restore trails and habitat, protect wildlife, provide educational programs, and more. The Conservancy’s guided adventures, volunteer opportunities, wilderness services and bookstores help visitors of all ages connect with Yosemite. Learn more at yosemite.org 415-434-1782 NEW TITLES 2020 ART & PHOTOGRAPHY The Nature of Yosemite A Visual Journey Robb Hirsch Foreword by John Muir Laws The hardcover edition sold out within 3 months! Announcing a gorgeous paperback edition, just in time for the busy park season! Whether venturing deep into the wilderness or simply taking a few steps off a park road, Groveland photographer Robb Hirsch, a scientist by training, always brings back a captivating picture—and the story behind it. The ongoing search for the “Wow!” is his passion, and that passion comes through in each of his photographs. From his years of exploring, guiding, and studying the Sierra Nevada, Robb knows that understanding the natural processes underlying Yosemite can enhance one’s connection to the landscape. This book provides that enriching experience by pairing Robb’s photographs with insightful essays by the following Sierra luminaries in order to draw readers into a deeper relationship with their favorite national park. The result is a breathtaking book that will dazzle, enlighten, and inspire a deep appreciation for the nature of Yosemite. 978-1-930238-92-3 $27.00, paperback 144 pages, 11 x 11 inches ORDER TODAY [email protected] 03 NEW TITLES 2020 ART & PHOTOGRAPHY The Nature of Yosemite THE NATURE OF YOSEMITE 2021 Calendar A Visual Journey for 2021 Robb Hirsch Drawn from the recent remarkable book by Groveland photographer Robb Hirsch, this twelve-month wall calendar provides a stunning way for people to engage with their favorite national park all year long. -

Guide to the Norman Clyde-Robert C. Pavlik Collection, 1906-2009

Guide to the Norman Clyde-Robert C. Pavlik Collection, 1906-2009 http://lib.calpoly.edu/specialcollections/findingaids/ms164 Norman Clyde-Robert C. Pavlik Collection, 1906-2009 (bulk 1984-2008) Processed by Teresa Van Doren and Ken Kenyon, 2009; encoded by Byte Managers, 2009 Special Collections Department Robert E. Kennedy Library 1 Grand Avenue California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 Phone: 805/756-2305 Fax: 805/756-5770 Email: [email protected] URL: http://lib.calpoly.edu/specialcollections/ © 2009 Trustees of the California State University. All rights reserved. Table of Contents GUIDE TO THE NORMAN CLYDE-ROBERT C. PAVLIK COLLECTION, 1906-2009 1 DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY 4 TITLE: 4 COLLECTION NUMBER: 4 CREATORS: 4 ABSTRACT: 4 EXTENT: 4 LANGUAGE: 4 REPOSITORY: 4 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION 5 PROVENANCE: 5 ACCESS: 5 RESTRICTIONS ON USE AND REPRODUCTION: 5 PREFERRED CITATION: 5 ABBREVIATIONS USED: 5 INDEXING TERMS 6 SUBJECTS: 6 GENRES AND FORMS OF MATERIAL: 6 RELATED MATERIALS 6 RELATED COLLECTIONS: 6 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES 7 NORMAN CLYDE 7 ROBERT C. PAVLIK 8 SOURCES 9 SCOPE AND CONTENT 10 SERIES DESCRIPTION/FOLDER LIST 12 SERIES 1. NORMAN CLYDE PRIMARY SOURCES, 1906-C. 2000 12 A. CLYDE FAMILY RECORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHS 12 B. CORRESPONDENCE OF NORMAN CLYDE 12 C. ARTICLES BY NORMAN CLYDE 13 SERIES 2. RESEARCH FILES ON NORMAN CLYDE, 1910-2009 17 A. PAVLIK RESEARCH CORRESPONDENCE 17 B. CORRESPONDENCE OF NORMAN CLYDE FAMILY AND FRIENDS 19 C. PAVLIK RESEARCH AT INSTITUTIONS 20 SERIES 3. SUBJECT FILES AND SECONDARY SOURCES ON NORMAN CLYDE, 1923-2009 22 A. BACKGROUND SUBJECT FILES 22 -2- B. -

A Photographic History of the Sierra Peaks Section 1955-2015

A PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORY OF THE SIERRA PEAKS SECTION 1955-2015 A PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORY OF THE SIERRA PEAKS SECTION 1955-2015 Prepared by Bob Cates First Presented at SPS 60th Anniversary Banquet, Jan. 25, 2015 SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING – CLARENCE KING Clarence King Credited with first instance of ‘roping down’ in Sierra Nevada in 1864 SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING JOHN MUIR – CALIFORNIA’S FIRST RECREATIONAL MOUNTAINEER “The mountains are calling and I must go.” “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop away from you like leaves of Autumn.” SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING – SIERRA CLUB HIGH TRIPS Typical High Trip Mountaineering Outing – Circa 1906 SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING – SIERRA CLUB HIGH TRIPS High Trippers on Mt. Ritter, 1918 – Including Southern Sierrans Horsley, Bunn, Tracy, and Dawson SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING – SIERRA CLUB HIGH TRIPS Norman Clyde Clair Tappaan Will Colby HIGH TRIP GROUP IN YOSEMITE, 1921 SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING – SIERRA CLUB HIGH TRIPS Norman Clyde Guiding a Woman Climber, 1920s SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING – SIERRA CLUB HIGH TRIPS 1929 High Trip Included Climb of Mt. Ritter Led by Bill Horsfall SPS 60TH ANNIVERSARY, 1955-2015 ROOTS OF SIERRA CLIMBING – SIERRA CLUB HIGH TRIPS Sierra Club party ascending Mt. -

Wringing Light out of Stone

MOUNTAIN PROFILE THE PALISADES I DOUG ROBINSON Wringing Light out of Stone So this kid walks into the Palisades.... I was twenty, twenty-one—don’t remember. It was the mid-1960s, for sure. I’d been hanging in the Valley for a few seasons, wide-eyed and feeling lucky to be soaking up wisdom by holding the rope for Chuck Pratt, the finest crack climber of the Golden Age. Yeah, cracks: those stark highways up Yosemite’s smooth granite that only open up gradually to effort and humility. Later they begin to reveal another facet: shadowed, interior, drawing us toward hidden dimensions of our ascending passion. ¶ The Palisades, though, are alpine, which means they are even more fractured. It would take me a little longer to cut through to the true dimensions of even the obvious features. To my young imagination, they looked like the gleaming, angular granite in the too-perfect romantic pictures that I devoured out of Gaston Rébuffat’s mountaineering books. My earliest climbing partner, John Fischer, had already been there— crampons lashed to his tan canvas-and-leather pack—and he’d returned, wide-eyed, with the tale of having survived a starlit bivy on North Palisade. [Facing Page] Don Jensen climbing in the Palisades, Sierra Nevada, California, during the 1960s—captured in a photo that reflects the atmosphere of the French alpinist Gaston Rébuffat’s iconic images of the Alps. Many consider the Palisades to be the most alpine region of the High Sierra, although climate change has begun to affect the classic ice and snow climbs. -

Norman Clyde Papers, 1912-Circa 2002, Bulk 1923-1972

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf996nb44j No online items Finding Aid to the Norman Clyde Papers, 1912-circa 2002, bulk 1923-1972 Finding Aid written by Ria Sachs and Mary Millman; revised by Marjorie Bryer The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Norman Clyde BANC MSS 79/33 c 1 Papers, 1912-circa 2002, bulk 1923-1972 Finding Aid to the Norman Clyde Papers, 1912-circa 2002, bulk 1923-1972 Collection Number: BANC MSS 79/33 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Ria Sachs and Mary Millman; revised by Marjorie Bryer Date Completed: April 2007 © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Norman Clyde papers Date (inclusive): 1912-circa 2002, Date (bulk): bulk 1923-1972 Collection Number: BANC MSS 79/33 c Creators : Clyde, Norman, 1885-1972. Extent: Number of containers: 5 cartons, 1 boxLinear feet: 5.42 Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: The Norman Clyde Papers document the climbing adventures of, and offer insights into the life of, one of California's greatest mountaineers, and one of the foremost chroniclers of the Sierra Nevada range. They also help to preserve the history of mountaineering in the High Sierra. -

Galtfornta August OLOCY B Living Glee,Iers of Co Lifo Rn Io O,D,DA Ptcturestory

Singlecopy 251 ccEoA28(8) r69-r92 097s) GaLTFoRNTA August OLOCY b living glee,iers of Co lifo rn io o,D,DA PTcTUREsToRY MARY HILL,Geologist CaliforniaDivision of Mines and Geology In the 49 states south of Alaska, there are about I 100 glaciers.All are in the western states; Washington, Montana, California, and Wyoming have the lion's share (figure l, table l ). Much of the early work on California glaciers was done by pioneers of California geology--John Muir, Israel C. Russell,W. D. John- son, G. K. Gilbert, and A. C. Lawson. About 80 tiny glaciers lie in small cirques of the Cascades,Trinity Alps, and Sierra Nevada Ranges of a California (figure 2, table 2). These I interestingand accessibleglaciers are aa \ Table 1. Number and size of glaciers in the United States Modifiedfrom U.S.Geological Su rye State ApproxrmateTotal glacier numberof area in g laciers square miles Alaska 5000? About 17,000 't60 Washingtor 800 Wyoming 80 18 Montana 106 18 Oregon 38 8 California 80 Colorado 10? 1 ,ldaho 11? I 'I Nevada 0.1 Figure1. Areas of existingglaciers in the western United States.(exceptAlaska and Hawaii). Modified from Am e ri c an Geographical Society. Utah 1? Or,1? 9 Figure3. MiddlePalisade glacier is madeupof the patchesof ice to the lett.lce patchesand the snow fieldsto the right are part of the snow and ice field in the peak shadow of MiddlePalisade (hiddenfrom view by clouds)that includesthe glacierthat bears its name and about 3 other small glacierets.Middle palisade Figure 2. Map showing existing glacier is about 1 1/2miles long, making it the largesi in the SierraNevaoa. -

Yosemite 61(2)

NIHE PATH OF THE PUMA: BY JEFF LAHR A Day`in Search of Yosemite's Mountain Lions The mountain lion has proven to be an elusive cat both spearheading a four-year study of the puma in the in nature and in name. Although it roams throughout Yosemite region, with the dual goals of gaining informa- most of the western United States, its solitary nature has tion regarding the mountain lion 's role and niche in its caused its habits to remain somewhat of a mystery. natural environment and using this information to mini- Several aliases - puma, cougar, panther, and catamount - mize threats to human safety. have even further clouded its true identity, but despite its elusiveness, most people possess strong opinions of this Depending on the context, cat and its reputation as one of nature's most efficient predators . Since very few people have ever witnessed the the mountain lion is alternately beast in the wild, it seems ironic that this cat, North America's only lion, provokes such strong reactions portrayed as a cuddly kitten among environmentalists, wildlife managers, politicians or a cold-blooded killer, and even the general public. Most often, the soft imprint of its paw in the dusty shoulder of the road provides the but in reality it is simply only clue that a mountain lion, or cougar, is on the prowl. The cougar's evasive manner has made it difficult to an effective predator occupying study. The nature of mountain lions has eluded biologists in the past and little can be predicted with certainty about a secure spot at the top Cover photo mountain lions' behaviors and habits .