Henryk Adamczuk Residualisation, Polarisation and Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- A02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL

AGENDA ITEM NO.-.-.-.- a02 NORTH LANARKSHIRE COUNCIL REPORT To: COMMUNITY SERVICES COMMITTEE Subject: COMMUNITY GRANTS SCHEME GRANTS TO PLAYSCHEMES - SUMMER 2001 JMcG/ Date: 12 SEPTEMBER 2001 Ref: BP/MF 1. PURPOSE 1.1 At its meeting of 15 May 2001 the community services (community development) sub committee agreed to fund playschemes operating during the summer period and in doing so agreed to apply the funding formula adopted in earlier years. The committee requested that details of the awards be reported to a future meeting. Accordingly these are set out in the appendix. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 It is recommended that the committee: (i) note the contents of the appendix detailing grant awards to playschemes which operated during the summer 2001 holiday period. Community Grants Scheme - Playschemes 2001/2002 Playschemes Operating during Summer 2001 Loma McMeekin PSOl/O2 - 001 Bellshill Out of School Service Bellshill & surrounding area 10 70 f588.00 YMCA Orbiston Centre YMCA Orbiston Centre Liberty Road Liberty Road Bellshill Bellshill MU 2EU MM 2EU ~~ PS01/02 - 003 Cambusnethan Churches Holiday Club Irene Anderson Belhaven, Stewarton, 170 567.20 Cambusnethan North Church 45 Ryde Road Cambusnethan, Coltness, Kirk Road Wishaw Newmains Cambusnethan ML2 7DX Cambusnethan Old & Morningside Parish Church Greenhead Road Cambusnethan Mr. Mohammad Saleem PSO 1/02 - 004 Ethnic Junior Group North Lanarkshire 200 6 f77.28 Taylor High School 1 Cotton Vale Carfin Street Dalziel Park New Stevenston Motherwell. MLl 5NL PSO1102-006 Flowerhill Parish Church/Holiday -

3, Java Street , Forgewood, Motherwell, Ml1

HOME REPORT 3 JAVA STREET FORGEWOOD MOTHERWELL ML1 3SF ENERGY REPORT YouEnergy can use this Performance document to: Certificate (EPC) Scotland Dwellings 3 JAVA STREET, FORGEWOOD, MOTHERWELL, ML1 3SF Dwelling type: Mid-terrace house Reference number: 9144-1024-3201-8740-8204 Date of assessment: 14 September 2020 Type of assessment: RdSAP, existing dwelling Date of certificate: 14 September 2020 Approved Organisation: Elmhurst Total floor area: 56 m2 Main heating and fuel: Boiler and radiators, mains Primary Energy Indicator: 211 kWh/m2/year gas You can use this document to: • Compare current ratings of properties to see which are more energy efficient and environmentally friendly • Find out how to save energy and money and also reduce CO2 emissions by improving your home Estimated energy costs for your home for 3 years* £1,554 See your recommendations report for more Over 3 years you could save* £363 information * based upon the cost of energy for heating, hot water, lighting and ventilation, calculated using standard assumptions Very energy efficient - lower running costs Current Potential Energy Efficiency Rating (92 plus) A 92 This graph shows the current efficiency of your home, (81-91) B taking into account both energy efficiency and fuel costs. The higher this rating, the lower your fuel bills (69-80) C 73 are likely to be. (55-68) D Your current rating is band C (73). The average rating for EPCs in Scotland is band D (61). (39-54 E (21-38) The potential rating shows the effect of undertaking all F of the improvement measures listed within your (1-20) G recommendations report. -

1, Forbes Drive , Forgewood, Motherwell, ML1

HOME REPORT 1 Forbes Drive Forgewood Motherwell ML1 3UP ENERGY REPORT YouEnergy can use this Performance document to: Certificate (EPC) Scotland Dwellings 1 FORBES DRIVE, FORGEWOOD, MOTHERWELL, ML1 3UP Dwelling type: Semi-detached house Reference number: 2290-4761-0229-1221-1083 Date of assessment: 26 October 2018 Type of assessment: RdSAP, existing dwelling Date of certificate: 30 October 2018 Approved Organisation: Elmhurst Total floor area: 62 m2 Main heating and fuel: Boiler and radiators, mains Primary Energy Indicator: 211 kWh/m2/year gas You can use this document to: • Compare current ratings of properties to see which are more energy efficient and environmentally friendly • Find out how to save energy and money and also reduce CO2 emissions by improving your home Estimated energy costs for your home for 3 years* £1,653 See your recommendations report for more Over 3 years you could save* £261 information * based upon the cost of energy for heating, hot water, lighting and ventilation, calculated using standard assumptions Very energy efficient - lower running costs Current Potential Energy Efficiency Rating (92 plus) A This graph shows the current efficiency of your home, (81-91) B 89 taking into account both energy efficiency and fuel costs. The higher this rating, the lower your fuel bills (69-80) C 72 are likely to be. (55-68) D Your current rating is band C (72). The average rating for EPCs in Scotland is band D (61). (39-54 E (21-38) The potential rating shows the effect of undertaking all F of the improvement measures listed within your (1-20) G recommendations report. -

Forgewood Family Learning Centre Day Care of Children

Forgewood Family Learning Centre Day Care of Children 167 Fife Drive Forgewood Motherwell ML1 3UT Telephone: 01698 274909 Type of inspection: Unannounced Completed on: 30 August 2019 Service provided by: Service provider number: North Lanarkshire Council SP2003000237 Service no: CS2003015409 Inspection report About the service Forgewood Family Learning Centre was previously registered with the Care Commission and transferred its registration to the Care Inspectorate when it was formed in 2011. The service is registered to provide a care service to a maximum of 55 children aged from two years to those not yet attending primary school. A maximum of 15 children can be cared for who are under three years old. The provider of the service is North Lanarkshire Council. Care is provided from a detached one level property in the Forgewood area of Motherwell. Children are accommodated within two large bright interconnecting playrooms which have direct access to two secure gardens. The centre is based at the heart of the community, and is close to parks, shops, the community centre and other local amenities. The nursery has a set of aims which includes: "At Forgewood Family Learning Centre we will ensure all children become the very best they can be. We will do this by providing a happy, inclusive, quality learning environment where every child is valued, listened to, respected, and where their aspirations and dreams are nurtured in promoting their thirst for lifelong learning". We check services are meeting the principles of Getting it Right for Every Child (also known as GIRFEC), Scotland's national approach to improving outcomes and wellbeing for children by offering the right help at the right time from the right people. -

Lanarkshire Bus Guide

Lanarkshire Bus Guide We’re the difference. First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 1 First Bus is one of Britain’s largest bus operators. We operate around a fifth of all local bus services outside London. As a local employer, we employ 2,400 people across Greater Glasgow & Lanarkshire, as well as offering a range of positions, from becoming a qualified bus technician to working within our network team or human resources. Our 80 routes criss-cross Glasgow, supplied by 950 buses. Within Lanarkshire we have 483 buses on 11 routes, helping to bring the community together and enable everyday life. First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 2 Route Frequency From To From every East Kilbride. Petersburn 201 10 min Hairmyres Glasgow, From every Buchanan Bus Overtown 240 10 min Station From every North Cleland 241 10 min Motherwell From every Holytown/ Pather 242 20 min Maxim From every Forgewood North Lodge 244 hour From every Motherwell, Newarthill, 254 10 min West Hamilton St Mosshall St Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 255 30 min Bus Station Station Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 263 30 min Bus Station Station From every Hamilton Newmains/Shotts 266 6 min Bus Station Glasgow, From every Hamilton Buchanan Bus 267 10 min Bus Station Station First Bus Lanarkshire Guide 3 Fare Zone Map Carnbroe Calderbank Chapelhall Birkenshaw Burnhead Newhouse 266 to Glasgow 240 to Petersburn 242 NORTH 201 254 Uddingston Birkenshaw Dykehead Holytown LANARKSHIRE Shotts Burnhead LOCAL ZONE Torbothie Bellshill Newarthill 241 93 193 X11 Stane Flemington Hartwood Springhill -

Quarterly Performance Report

Quarterly Performance Report 2014-15 Quarter 2 SCOTTISH FIRE AND RESCUE SERVICE November 2014 Report Prepared by Performance Data Services About the statistics in this report The activity totals and other statistics quoted in this report are internal management information published in the interests of transparency and openness. They are provisional in nature and subject to change as a result of ongoing quality assurance and review. Because all statistics quoted are provisional there may be differences in the period totals quoted in our reports after original publication which result from revisions or additions to the data on our systems. The Scottish Government publishes Official Statistics each year which allow for comparisons to be made over longer periods of time. Quarterly Quarterly Performance Report 1 Quarterly Performance Report 2014-15 Quarter 2 Table of Contents KEY POINTS AT A GLANCE .......................................................................................... 3 SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT TARGETS ................................................................................ 4 RESPONSE AND RESILIENCE ......................................................................................... 8 TOP 15 INCIDENT TYPES ATTENDED ........................................................................... 8 CALL HANDLING TIMES .......................................................................................... 9 RESPONSE TIMES ................................................................................................ -

240 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

240 bus time schedule & line map 240 Overtown - Glasgow via Wishaw, Motherwell & View In Website Mode Bellshill The 240 bus line (Overtown - Glasgow via Wishaw, Motherwell & Bellshill) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Birkenshaw: 4:43 PM - 11:04 PM (2) Glasgow: 4:33 AM - 10:04 PM (3) Motherwell: 6:24 AM - 11:29 PM (4) Overtown: 6:10 AM - 10:29 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 240 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 240 bus arriving. -

The Long Term Integration of Gateway Protection Programme Refugees in Motherwell, North Lanarkshire

UWS-Oxfam Partnership, Collaborative Research Reports Series Series Editors: Chik Collins and Francis Stuart The Long Term Integration of Gateway Protection Programme Refugees in Motherwell, North Lanarkshire Duncan Sim and Kait Laughlin School of Media, Culture and Society, University of the West of Scotland Paisley Campus, PA1 2BE October 2014 1 Funded by the UWS-Oxfam Partnership 1 This report was funded by the UWS-Oxfam Partnership, however it does not necessarily reflect the views or policy of Oxfam Scotland and the contents are the sole responsibility of the authors. The University of the West of Scotland-Oxfam Partnership: ‘For a more equitable and sustainable Scotland’ The UWS-Oxfam Partnership is a formally established relationship between the two organisations, underpinned by a Memorandum of Understanding. The Partnership emerged as a result of collaborative work between UWS staff and Oxfam and its community partner organisations, revolving around the development of Oxfam’s antipoverty advocacy and campaigning in Scotland. The Partnership comprises: • A Research and Knowledge Exchange linking UWS academics and Oxfam and its community partners in collaborative projects; • A programme of placements and work-related learning and volunteering opportunities, enabling UWS students to contribute to the work of Oxfam and its community partners, while learning and developing their experience and skills; • The UWS-Oxfam Policy Forum, which brings all of these partners together with a broad range of external organisations from across all sectors of Scottish society, to discuss key questions and to inform understanding and engagement with both existing and emergent issues. The Partnership publishes a series of Collaborative Research Reports, edited by Chik Collins (UWS) and Francis Stuart (Oxfam), which, together with other information on the activities of the Partnership, can be found at the following link: http://uwsoxfampartnership.org.uk/category/oxfam/ Report No. -

FOR SALE POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE 174-178 Bellshill Road, Motherwell, ML1 3SG

DEVELOPMENT SITE 0.110ha NEWHUT ROAD (0.271ac) BELLSHILL ROAD LOGANS ROAD FOR SALE POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE 174-178 Bellshill Road, Motherwell, ML1 3SG Regular shaped, level development site. Located close to Motherwell town centre. Close proximity to Braidhurst Industrial Estate. Site area of 0.110 hectares (0.271 acres), or thereby. Offers over £40,000. Commercial Department Unit 3 Cadzow Park, 82 Muir Street, Hamilton ML3 6BJ dmhall.co.uk 01698 284 939 LOCATION Further enquiries should be directed to North Lanarkshire Council The subjects comprise the site of the former Eagle Inn, which has on 01236 632500. since been demolished, and occupies an extremely prominent location on the east side of Bellshill Road close to the junction SITE AREA of Newhut Road and lying approximately one mile north west of From Ordnance Survey mapping systems we calculate the site Motherwell town centre. extends to 0.110 hectares (0.271 acres), or thereby. The site is sandwiched between the residential area of Forgewood lying to the north and the Braidhurst Industrial Estate lying to the PRICE south with nearby commercial operators including Moorhead Offers over £40,000 are invited for our client’s heritable interest in & McGavin, Glenisla Kilts, Thornrbidge Timber Merchants and the property, exclusive of VAT (if applicable). Direct Rail Services. LEGAL COSTS Motherwell is located in North Lanarkshire region approximately Each party to be responsible for their own legal costs incurred 10 miles east of Glasgow. The town has a population in excess during transactions. of 30,000 persons and is located between the M8 and M74 motorways. -

Tender Register CP's and AC's

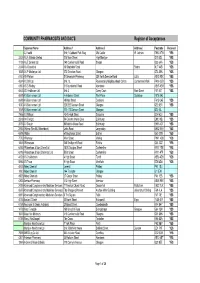

COMMUNITY PHARMACISTS AND DAC'S Register of Acceptances Dispenser Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Postcode Received 4C Health Unit 1 Oakbank Park Way Mid Calder W. Lothian EH53 0TH YES 3232 A & A Gilbride Limited 275 Main Street High Blantyre G72 0DL YES 1112 A & E Ceresa Ltd 140 Cumbernauld Road Stepps G33 6HA YES 3084 A & I Crawford 19 Shottskirk Road Shotts ML7 4AB YES 1535 A & P MacIntyre Ltd 273 Stonelaw Road Glasgow G73 3RN YES 4160 A B Watson St Devenicks Pharmacy 359 North Deeside Road Cults AB15 9SX YES 4624 A C Still Ltd Unit 1a, Ravenscraig Neighbourhood Centre Cumberland Walk PA16 0UD YES 4200 A D B Findlay 31 Fountainhall Road Aberdeen AB15 4EW YES 6663 A D Healthcare Ltd Unit 3 Carey Court Main Street FK7 8BT YES 6688 A G Bannerman Ltd 4 Anderson Street Well Place Dunblane FK15 9AJ 6689 A G Bannerman Ltd 48 High Street Dunblane FK15 0AE YES 1030 A G Bannerman Ltd 220/222 Saracen Street Glasgow G22 5ER YES 1059 A G Bannerman Ltd 171-173 Saracen Street Glasgow G22 5JL 7566 A G Milligan 43/45 High Street Sanquhar DG4 6DJ YES 2243 A H Tod Ltd 84 Colinton Mains Drive Edinburgh EH13 9BJ YES 2087 A J Glauch 96 Niddrie Mains Road Edinburgh EH16 4DT YES 2106 A Kemp (Mrs M J Marchbank) Links Road Longniddry EH32 0NH YES 6589 A Millar 67 Buchanan Street Balfron G63 0TW YES 7076 A Ramsay Main Street Mallaig PH41 4QB YES 1404 A Robertson 248 Smithycroft Road Riddrie G33 2QZ YES 6093 A Robertson & Son (Chem)Ltd 18/20 Douglas Street Dunfermline KY12 7EB YES 6219 A Robertson & Son (Chemists) Ltd Elliot Street Dunfermline KY11 4TF YES -

2019 Boxing Scotland Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Performance .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Training .......................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GB Boxing Programme ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Investment ......................................................................................................................................................................11 Organisational Change .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Finances .......................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Domestic Championships ......................................................................................................................................... 16 Development East & West Region .......................................................................................................................... -

Impacts of Commercial Property Development

IMPACTS OF COMMERCIAL PROPERTY DEVELOPMENT Final Report BEIS Research Paper Number 2019/001 July 2018 Contents Executive Summary____________________________________________________ 6 1 Introduction ______________________________________________________ 11 1.1 Introduction and objectives ________________________________________ 11 1.2 Workplan and Phases _____________________________________________ 12 1.3 Report structure _________________________________________________ 12 2 Summary of Literature Review _______________________________________ 14 2.1 Introduction ___________________________________________________ 14 2.2 Impact results from previous studies _______________________________ 14 2.3 Methodologies from previous studies ______________________________ 16 3 Developing the Databases of New Commercial Property Developments and Firm- Level Data ___________________________________________________________ 18 3.1 Introduction ____________________________________________________ 18 3.2 Property Database _______________________________________________ 18 Funding source ____________________________________________________ 20 Property categories _________________________________________________ 20 3.3 Firm level data __________________________________________________ 24 3.4 Augmented property database _____________________________________ 25 4 Impact on local units moving to a new Commercial Property Development ___ 29 4.1 Introduction ___________________________________________________ 29 4.2 Approach _____________________________________________________