The Multiple Sites of Conservative Legal Ideology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert L. Tsai

ROBERT L. TSAI Professor of Law American University The Washington College of Law 4300 Nebraska Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20016 202.274.4370 [email protected] roberttsai.com EDUCATION J.D. Yale Law School, 1997 The Yale Law Journal, Editor, Volume 106 Yale Law and Policy Review, Editor, Volume 12 Honorable Mention for Oral Argument, Harlan Fiske Stone Prize Finals, 1996 Morris Tyler Moot Court of Appeals, Board of Directors Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic B.A. University of California, Los Angeles, History & Political Science, magna cum laude, 1993 Phi Beta Kappa Highest Departmental Honors (conferred by thesis committee) Carey McWilliams Award for Best Honors Thesis: Building the City on the Hilltop: A Socio-Political Study of Early Christianity ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Temple University, Beasley School of Law Clifford Scott Green Chair and Visiting Professor of Constitutional Law, Fall 2019 Courses: Fourteenth Amendment History and Practice, Presidential Leadership Over Individual Rights American University, The Washington College of Law Professor of Law, May 2009—Present Associate Professor of Law (with tenure), June 2008—May 2009 Courses: Constitutional Law, Criminal Procedure, Jurisprudence, Presidential Leadership and Individual Rights, The First Amendment University of Georgia Law School Visiting Professor, Semester in Washington Program, Spring & Fall 2012 Course: The American Presidency and Individual Rights University of Oregon School of Law Associate Professor of Law (with tenure), 2007-08 Assistant Professor, 2002-07 2008 Lorry I. Lokey University Award for Faculty Excellence (via nomination & peer review) 2007 Orlando John Hollis Faculty Teaching Award Courses: Constitutional Law, Federal Courts, Free Speech, Equality, Religious Freedom, Civil Rights Litigation Yale University, Department of History Teaching Fellow, 1996, 1997 CLERKSHIPS The Honorable Hugh H. -

Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum to Claims Court - Law360

9/24/2020 Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum To Claims Court - Law360 Portfolio Media. Inc. | 111 West 19th Street, 5th floor | New York, NY 10011 | www.law360.com Phone: +1 646 783 7100 | Fax: +1 646 783 7161 | [email protected] Senate Confirms Kirkland Alum To Claims Court By Julia Arciga Law360 (September 22, 2020, 2:46 PM EDT) -- A Maryland-based former Kirkland & Ellis LLP associate will become a judge of the Court of Federal Claims for a 15-year term, after the U.S. Senate on Tuesday confirmed him by a 66-27 vote. Edward H. Meyers is a partner at Stein Mitchell Beato & Missner LLP, litigating bid protests, breach of contract disputes and copyright infringement. While at the firm, he served as counsel for one of the collection agencies in a 2018 consolidated protest action challenging the U.S. Department of Education's solicitation for student loan debt collection services. He clerked with Federal Claims Judge Loren A. Smith between 2005 and 2006 before spending six years as a Kirkland associate, where he worked as a civil litigator handling securities, government contracts, construction, insurance and statutory claims. He earned his bachelor's degree from Vanderbilt University and his law degree summa cum laude from Catholic University of America's Columbus School of Law — where he joined the Federalist Society and still remains a member. Judiciary committee members Sens. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., had raised questions about Meyers' Federalist Society affiliation before Tuesday's vote, and he confirmed that he did speak to fellow members throughout his nomination process. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2017 Remarks at the National Rifle Association Leadership Forum in Atlanta, Georgia April 28, 2017 Thank you, Chris, for that kind introduction and for your tremendous work on behalf of our Second Amendment. Thank you very much. I want to also thank Wayne LaPierre for his unflinching leadership in the fight for freedom. Wayne, thank you very much. Great. I'd also like to congratulate Karen Handel on her incredible fight in Georgia Six. The election takes place on June 20. And by the way, on primaries, let's not have 11 Republicans running for the same position, okay? [Laughter] It's too nerve-shattering. She's totally for the NRA, and she's totally for the Second Amendment. So get out and vote. She's running against someone who's going to raise your taxes to the sky, destroy your health care, and he's for open borders—lots of crime—and he's not even able to vote in the district that he's running in. Other than that, I think he's doing a fantastic job, right? [Laughter] So get out and vote for Karen. Also, my friend—he's become a friend—because there's nobody that does it like Lee Greenwood. Wow. [Laughter] Lee's anthem is the perfect description of the renewed spirit sweeping across our country. And it really is, indeed, sweeping across our country. So, Lee, I know I speak for everyone in this arena when I say, we are all very proud indeed to be an American. -

The Tea Party Movement As a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 Albert Choi Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/343 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2014 i Copyright © 2014 by Albert Choi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. THE City University of New York iii Abstract The Tea Party Movement as a Modern Incarnation of Nativism in the United States and Its Role in American Electoral Politics, 2009-2014 by Albert Choi Advisor: Professor Frances Piven The Tea Party movement has been a keyword in American politics since its inception in 2009. -

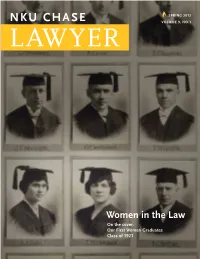

NKU CHASE Volume 9, No.1

Spring 2012 nKu CHASe volume 9, no.1 Women in the law on the cover: our First Women graduates Class of 1921 From the Dean n this issue of NKU Chase Lawyer, we celebrate the success of our women graduates. The law school graduated its first women in 1921. Since then, women have continued to be part of the Interim Editor IChase law community and have achieved success in a David H. MacKnight wide range of fields. At the same time, it is important to Associate Dean for Advancement recognize that there is much work to be done. Design If we are to be true to our school’s namesake, Chief Paul Neff Design Justice Salmon P. Chase, Chase College of Law should be a leader in promoting gender diversity. As Professor Photography Richard L. Aynes, a constitutional scholar, pointed out Wendy Lane in his 1999 article1, Chief Justice Chase was an early Advancement Coordinator supporter of the right of women to practice law. In 1873, then Chief Justice Chase cast John Petric the sole dissenting vote in Bradwell v. Illinois, a case in which the Court in a 8-1 decision Image After Photography LLC upheld the Illinois Supreme Court’s refusal to admit Myra Bradwell to the bar on the Bob Scheadler grounds that she was a married woman. The Court’s refusal to grant Mrs. Bradwell the Daylight Photo relief she sought is all the more notable because three of the justices who voted to deny her relief had previously dissented vigorously in The Slaughter-House Cases, a decision in Timothy D. -

The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies 2009 Annual Report

The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies 2009 Annual Report “The Courts must declare the sense of the law; and if they should be disposed to exercise will instead of JUDGMENT, the consequences would be the substitution of their pleasure for that of the legislative body.” The Federalist 78 THE FEDERALIST SOCIETY aw schools and the legal profession are currently strongly dominated by a L form of orthodox liberal ideology which advocates a centralized and uniform society. While some members of the academic community have dissented from these views, by and large they are taught simultaneously with (and indeed as if they were) the law. The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies is a group of conservatives and libertarians interested in the current state of the legal order. It is founded on the principles that the state exists to preserve freedom, that the separation of governmental powers is central to our Constitution, and that it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be. The Society seeks both to promote an awareness of these principles and to further their application through its activities. This entails reordering priorities within the legal system to place a premium on individual liberty, traditional values, and the rule of law. It also requires restoring the recognition of the importance of these norms among lawyers, judges, law students and professors. In working to achieve these goals, the Society has created a conservative intellectual network that extends to all levels of the legal community. -

Conversations with Bill Kristol

Conversations with Bill Kristol Guest: Adam J. White Research Scholar, American Enterprise Institute Executive Director, George Mason Law School’s C. Boyden Gray Center Taped September 11, 2019 Table of Contents I. On the Supreme Court Today (0:15 – 44:19) II: The Conservative Legal Movement (44:19 – 1:21:17) I. On the Supreme Court Today (0:15 – 44:19) KRISTOL: Hi, I’m Bill Kristol. Welcome to CONVERSATIONS. I’m joined by my friend, Adam White, who has recently moved from The Hoover Institution to The American Enterprise Institute, where you’re – what’s your distinguished title there? Visiting? Resident Scholar? WHITE: Resident Scholar. KRISTOL: Did you have the same high title at Hoover, or was it just a visiting scholar? You were a resident scholar there. [Laughter] WHITE: I felt appreciated at Hoover too. KRISTOL: That’s good, yes. Anyway AEI has a new program in Social, Cultural and Constitutional Studies, which is great and you’re going to be a key part of that. You’ve obviously been a very – a lawyer and a commentator on all matters legal, judicial, the courts and the administrative state for The Weekly Standard and many other journals. And we had a conversation previously about the courts and the administrative state, before the Trump administration began I guess, I think – right? WHITE: Yeah. KRISTOL: But today we’re going to talk about the Judiciary. Kind of an important topic, a key talking point of Trump supporters, and maybe legitimately so. And I guess I’d like to begin with sort of 30,000 feet. -

Olin Foundation in 1953, Olin Embarked on a Radical New Course

THE CHRONICLE REVIEW How RightWing Billionaires Infiltrated Higher Education By Jane Mayer FEBRUARY 12, 2016 If there was a single event that galvanized conservative donors to try to wrest control of higher education in America, it might have been the uprising at Cornell University on April 20, 1969. That afternoon, during parents’ weekend at the Ithaca, N.Y., campus, some 80 black students marched in formation out of the student union, which they had seized, with their clenched fists held high in blackpower salutes. To the shock of the genteel Ivy League community, several were brandishing guns. At the head of the formation was a student who called himself the "Minister of Defense" for Cornell’s AfroAmerican Society. Strapped across his chest, Pancho Villastyle, was a sashlike bandolier studded with bullet cartridges. Gripped nonchalantly in his right hand, with its butt resting on his hip, was a glistening rifle. Chin held high and sporting an Afro, goatee, and eyeglasses reminiscent of Malcolm X, he was the face of a drama so infamous it was regarded for years by conservatives such as David Horowitz as "the most disgraceful occurrence in the history of American higher education." John M. Olin, a multimillionaire industrialist, wasn’t there at Cornell, which was his alma mater, that weekend. He was traveling abroad. But as a former Cornell trustee, he could not have gone long without seeing the iconic photograph of the armed protesters. What came to be known as "the Picture" quickly ricocheted around the world, eventually going on to win that year’s Pulitzer Prize. -

Exhibit a Case 1:20-Cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 2 of 20

Case 1:20-cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 1 of 20 Exhibit A Case 1:20-cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 2 of 20 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK THE CLEMENTINE COMPANY, LLC No. 1:20-cv-08899-CM d/b/a THE THEATER CENTER; PLAYERS THEATRE MANAGEMENT FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT CORP. d/b/a THE PLAYERS THEATRE; WEST END ARTISTS COMPANY d/b/a THE ACTORS TEMPLE THEATRE; SOHO PLAYHOUSE INC. d/b/a SOHO PLAYHOUSE; CARAL LTD. d/b/a BROADWAY COMEDY CLUB; and DO YOU LIKE COMEDY? LLC d/b/a NEW YORK COMEDY CLUB Plaintiffs, -against- ANDREW M. CUOMO, in his official capacity as Governor of the State of New York; BILL DE BLASIO, in his official capacity as Mayor of New York City, Defendants. 1. Plaintiffs The Clementine Company, LLC d/b/a The Theater Center; Players Theatre Management Corp. d/b/a The Players Theatre; West End Artists Company d/b/a The Actors Temple Theatre; SoHo Playhouse Inc. d/b/a SoHo Playhouse; Caral Ltd. d/b/a Broadway Comedy Club; and Do You Like Comedy? LLC d/b/a New York Comedy Club for their Complaint against Defendants Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio, allege as follows: 1 Case 1:20-cv-08899-CM Document 74-1 Filed 05/05/21 Page 3 of 20 INTRODUCTION 2. This civil rights lawsuit seeks to vindicate the constitutional rights of free speech and equal protection for the Plaintiff theaters and comedy clubs, which have been subject to unequal closure orders for more than a year. -

2020 Federalist Society 1L Welcome Letter

August 2020 President's Welcome to 1L's As President of the NSU Federalist Society, I personally would like to welcome you to the Shepard Broad College of Law. Over the next three years you will be trying to learn how our legal system works and what the law is. You may also learn how much you did not know about our federal system of government and its Constitutional underpinnings (what 8th grade civics never taught you). Unfortunately, some instructors may focus on how they think the law ought to be. This may be understandable in a university environment where practicality gives way to theory. However, theirs is not the only view of the world of law and that is one reason for The Federalist Society. The Society seeks to broaden the debate and provide an alternative view to that often encountered in law schools across the nation. To quote from The Federalist Society's statement of purpose: "Law schools and the legal profession are currently strongly dominated by a form of orthodox liberal ideology which advocates a centralized and uniform society. While some members of the academic community have dissented from these views, by and large they are taught simultaneously with (and indeed as if they were) the law. "The Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies is a group of conservatives and libertarians interested in the current state of the legal order. It is founded on the principles that the state exists to preserve freedom, that the separation of governmental powers is central to our Constitution, and that it is emphatically the province and duty of the judiciary to say what the law is, not what it should be. -

Crystal Reports

CLE Course Sponsors (listed alphabetically by abbreviation) Thursday, December 31, 2020 Nym Sponsor Address Contact Phone , - ( ) - 1031EE 1031 Exchange Experts LLC 8101 E Prentice Ave #400 Grnwd Vill , CO 80111- J Sides 866-694-0204 Kcc 2335 Alaska Avenue El Segundo, CA 90245- H Schlager (310) 751-1841 21STCC 21st Communications Comp 405 S Humboldt St Denver, CO 80209 G Meyers 303 298 1090 360ADV 360 Advocacy Inst 1103 Parkview Blvd Colo Spgs, CO 80905- K Osborn ( 71) 957-8535 4LEVE 4L Events Llc 2609 Production Road Virginia Beach, VA 23454- A Millard (800) 241-3333 AAA Amer Arbitration Assoc 13455 Noel Road #1750 Dallas, TX 75240- C Rumney (972) 774-6927 AAAA Amer Acad Of Adoption Attys 2930 E. 96Th Street Indianapolis, IN 46240- E Freeby (817) 338-4888 AAACPA Amer Assn Of Atty Cpas 8647 Richmond Hwy, #639 Alexandria, VA 22309- N Ratner (703) 352-8064 AAAEXE Amer Assn of Airport Executive , S Dickerson 703 824 0500 AAALS Assn of Amer Law Schools 1201 Connecticut Ave #800 Wash, DC 20036 J Bauman 202 269 8851 AAARTA Amer Acad Asst Repo Tech Attys Po Box 33053 Wash, DC 20033- D Crouse (618) 344-6300 AABA Asian Amer Bar Assn 10 Emerson St #501 Denver, CO 80218 c/o Ravi Kanwal 303 781 4855 AABAA Advocates Against Batt & Abuse PO Box 771424 Steamboat Spgs, , CO 80477- D Moore (970) 879-2034 AACLLC AA-Adv Appraisals Consulting 436 E Main St #C Montrose, CO 81401 M W Johnson 970 249 1420 AADC Arizona Assn of Defense Coun 3507 N Central Ave #202 Phoenix, AZ 85012 602 212 2505 AAEL Equipment Leasing Assn 1625 Eye Street Nw Washington, DC 20006- -

Federalist Society

Project of the New Features at The E.L. Wiegand Th e Federalist Society Journal of the Practice Groups www.fed-soc.org Engage: Federalist Society Practice Groups The Journal Special Issue: SUPREME COURT RETROSPECTIVE of the NOTA BENE Federalist Federal Preemption at the Supreme Court by Daniel E. Troy & Rebecca K. Wood SCOTUScast Justice Kennedy’s Stricter Scrutiny Originally Speaking Society and the Future of Racial Diversity Promotion Multimedia Archive by Nelson Lund Practice The Supreme Court’s 2005-2008 Securities Law Trio by Allen Ferrell Groups The Federalist Society NONPROFIT ORG. for Law & Public Policy Studies U.S. POSTAGE The Supreme Court’s 21st Century Trajectory in Criminal Cases PAID 1015 18th Street, N.W., Suite 425 WASHINGTON, DC by Tom Gede, Kent Scheidegger & Ron Rychlak PERMIT NO. 5637 Washington, D.C. 20036 International or Foreign Law as an Interpretive Volume Aid in Supreme Court Jurisprudence by Roger P. Alford 9, Issue Debunking the Myth of a Pro-Employer Supreme Court by Daniel J. Davis 3 October The 2008 Presidential Election, the Supreme Court, and the Relationship of Church and State 2008 by Steffen Johnson & Adele Auxier BOOK REVIEWS The Dirty Dozen by Robert A. Levy & William Mellor The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement by Steven M. Teles Volume 9, Issue 3 October 2008 Practice Group Publications Committees Administrative Law & Regulation Free Speech & Election Law Christian Vergonis, Chairman Reid Alan Cox, Chairman Daren Bakst, Vice-Chairman Francis J. Menton, Jr., Vice Chairman Civil Rights Intellectual Property Brian T. Fitzpatrick, Chairman Mark Schultz, Chairman Steven Tepp & Adam Mossoff , Vice Chairmen Corporations, Securities & Antitrust Michael Fransella, Chairman International & National Security Law Carrie Darling, Robert T.