Introduction Since Its Creation Almost a Century Ago, Glacier National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIAD CORP (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 9, 2012 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2011 or ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number: 001-11015 VIAD CORP (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 36 -1169950 State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization Identification No.) 1850 North Central Avenue, Suite 1900 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 -4565 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (602) 207-1000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $1.50 par value New York Stock Exchange Preferred Stock Purchase Rights New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined by Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes x No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Montana Official 2018-2019 Visitor Guide

KALISPELL MONTANA OFFICIAL 2018-2019 VISITOR GUIDE #DISCOVERKALISPELL 888-888-2308 DISCOVERKALISPELL.COM DISCOVER KALISPELL TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 DISCOVER KALISPELL 6 GETTING HERE 7 GLACIER NATIONAL PARK 10 DAY HIKES 11 SCENIC DRIVES 12 WILD & SCENIC 14 QUICK PICKS 23 FAMILY TIME 24 FLATHEAD LAKE 25 EVENTS 26 LODGING 28 EAT & DRINK 32 LOCAL FLAVOR 35 CULTURE 37 SHOPPING 39 PLAN A MEETING 41 COMMUNITY 44 RESOURCES CONNECTING WITH KALISPELL To help with your trip planning or to answer questions during your visit: Kalispell Visitor Information Center Photo: Tom Robertson, Foys To Blacktail Trails Robertson, Foys To Photo: Tom 15 Depot Park, Kalispell, MT 59901 406-758-2811or 888-888-2308 DiscoverKalispellMontana @visit_Kalispell DiscoverKalispellMontana Discover Kalispell View mobile friendly guide or request a mailed copy at: WWW.DISCOVERKALISPELL.COM Cover Photo: Tyrel Johnson, Glacier Park Boat Company’s Morning Eagle on Lake Josephine www.discoverkalispell.com | 888-888-2308 3 DISCOVER KALISPELL WELCOME TO KALISPELL Photos: Tom Robertson, Kalispell Chamber, Mike Chilcoat Robertson, Kalispell Chamber, Photos: Tom here the spirit of Northwest Montana lives. Where the mighty mountains of the Crown of the Continent soar. Where the cold, clear Flathead River snakes from wild lands in Glacier National Park and the Bob WMarshall Wilderness to the largest freshwater lake in the west. Where you can plan ahead for a trip of wonder—or let each new moment lead your adventures. Follow the open road to see what’s at the very end. Lay out the map and chart a course to its furthest corner. Or explore the galleries, museums, and shops in historic downtown Kalispell—and maybe let the bakery tempt you into an unexpected sweet treat. -

100 Years at Lake Mcd

Voice of the Glacier Park Foundation ☐ Fall 2017 ☐ Volume XXXII, No. 2 SPERRY BURNS 100 Years at Lake McD (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.) In this issue: • Wildfire in Glacier and Waterton • Lake McDonald Evacuated • Embers Shower the Prince of Wales • Remembering the Night of the Grizzlies • Death and Survival in Glacier • The Demise of the Chalets • Giants in Glacier • Jammer Tales • A Many Glacier Reflection• Unprecedented Traffic in the Park • The Twelve Days of Waiting • Inside News of the Summer of 2017 PARADISE LOST: Traffic Congestion in Glacier The fires of August in Glacier Park beyond past experience in Glacier. entrance sometimes were backed generated national attention. Gla- The problem certainly will recur in up onto Highway 2. Parking lots cier veterans were shocked to hear future seasons. It poses a very diffi- and campgrounds were filled by that the fire had destroyed the main cult management challenge. early morning. Emergency closures building at Sperry Chalets. Lake had to be imposed on traffic in the Glacier’s charm always has rested McDonald Lodge and its majestic Swiftcurrent, Two Medicine and in part on relatively light visitation. cedar-and-hemlock forest lay exposed Bowman valleys. We’ve all thought complacently that to destruction for weeks. The Prince Glacier is a cold park, far from large Twenty years ago, the Glacier Park of Wales Hotel, across the border in population centers, with limited Foundation had a large role in devel- Canada, nearly burned. September lodging. We’ve given thanks that we oping Glacier’s General Management finally brought deliverance, with don’t have traffic jams like those in Plan. -

Glacier NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA

Glacier NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA, UNITED STATES SECTION WATERTON-GLACIER INTERNATIONAL PEACE PARK Divide in northwestern Montana, contains nearly 1,600 ivy. We suggest that you pack your lunch, leave your without being burdened with camping equipment, you may square miles of some of the most spectacular scenery and automobile in a parking area, and spend a day or as much hike to either Sperry Chalets or Granite Park Chalets, primitive wilderness in the entire Rocky Mountain region. time as you can spare in the out of doors. Intimacy with where meals and overnight accommodations are available. Glacier From the park, streams flow northward to Hudson Bay, nature is one of the priceless experiences offered in this There are shelter cabins at Gunsight Lake and Gunsight eastward to the Gulf of Mexico, and westward to the Pa mountain sanctuary. Surely a hike into the wilderness will Pass, Fifty Mountain, and Stoney Indian Pass. The shelter cific. It is a land of sharp, precipitous peaks and sheer be the highlight of your visit to the park and will provide cabins are equipped with beds and cooking stoves, but you NATIONAL PARK knife-edged ridges, girdled with forests. Alpine glaciers you with many vivid memories. will have to bring your own sleeping and cooking gear. lie in the shadow of towering walls at the head of great ice- Trail trips range in length from short, 15-minute walks For back-country travel, you will need a topographic map carved valleys. along self-guiding nature trails to hikes that may extend that shows trails, streams, lakes, mountains, and glaciers. -

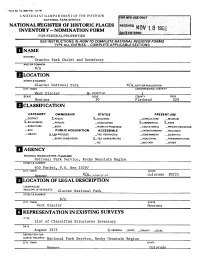

Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION

Form No. i0-306 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR lli|$|l;!tli:®pls NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES iliiiii: INVENTORY- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glacier National Park NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT West Glacier X- VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Montana 30 Flathead 029 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X.PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL X_RARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT N/AN PR OCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY _OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (Happlicable) ______National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region STREET & NUMBER ____655 Parfet, P.O. Box 25287 CITY. TOWN STATE N/A _____Denver VICINITY OF Colorado 80225 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Qlacier National STREET & NUMBER N/A CITY. TOWN STATE West Glacier Montana REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE List of Classified Structures Inventory DATE August 1975 X-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region CITY. TOWN STATE Colorado^ DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory are situated near the Swiftcurrent Pass in Glacier National Park at an elevation of 7,000 feet. -

NW Montana Joint Information Center Fire Update August 28, 2003, 10:00 AM

NW Montana Joint Information Center Fire Update August 28, 2003, 10:00 AM Center Hours 6 a.m. – 9 p.m. Phone # (406) 755-3910 www.fs.fed.us/nwacfire The East Side Reservoir Road #38 is CLOSED. Middle Fork River from Bear Creek to West Glacier is closed. Stanton Lake area is reopened. Highway 2 is NOT closed. Road #895 along the west side of Hungry Horse Reservoir is CLOSED. Stage II Restrictions are still in effect. Going to the Sun Road is still open. Blackfoot Lake Complex Includes the Beta Lake-Doris Ridge fires, Ball fire, and the Blackfoot lake complex of fires located on Flathead National Forest, south of Hungry Horse; Hungry Horse, MT. Fire Information (406) 755-3910, 387-4609. Size: Beta Lake – 518 acres total personnel: 580 containment: 0% Size: Doris Ridge- 1930 acres For entire complex containment: 0% Size: Blackfoot Lake Fires – 1,135 acres containment: 0% Size: Ball Fire – 314 acres containment: 5% * Current acreage was estimated at 6:00 pm on the 27th. Status: Lost Johnny, Beta and portions of the other fires experienced wind-driven torching and uphill runs. The Lost Johnny Fire increased in activity due to NNW winds. The Ball Fire moved to the east. The Beta Fire spotted across the Hungry Horse Reservoir into the Abbot Bay area. Active suppression on these spots continued into late evening. The Martin City community was on a precautionary evacuation alert with some residents in the far eastern sections on mandatory evacuation. This order was lifted at 10:00 am this morning with the notice that residents should remain on alert. -

Montana, Glacier National Park & the Canadian Rockies By

Montana, Glacier National Park Club presents G & the Canadian Rockies by Train 9 Days June 13, 2017 Highlights •Four National Parks •2 Nights aboard Empire Builder Train •Two Nights Whitefish, Montana •Glacier National Park •Going-to-the-Sun Highway •Kootenay National Park •Three Nights in Banff, Alberta •Moraine Lake & Valley of Ten Peaks •Lake Louise & Victoria Glacier •Icefields Parkway & Peyto Lake •Athabasca Glacier Snow Coach •The Fort Museum of NW Mounted Police •Waterton Lakes National Park Inclusions •2 Nights Rail Journey aboard Amtrak’s Empire Builder Train in Coach Class Seat •6 Nights Hotel Accommodations •9 Meals: 6-Breakfasts & 3-Dinners •Professional Tour Director •Motorcoach Transportation •Admissions per Itinerary •Comprehensive Sightseeing •Hotel Transfers •Cancellation Waiver & Post Departure Plan Booking Discount - Save $200 per couple!* Tour Rates Contact Information Booking #103040 Regular Rate: $3400 pp double Amanda Grineski • 529 G Avenue • Grundy Center, IA 50638 • (319) 824-5431 Booking Discount*: $3300 pp double Laura Kammarmeyer • 300 E. Main St. • Manchester, IA 52057 • (563) 927-3814 Single Supplement: +$950 Kelli Toomsen • 650 Main Street • Ackley, IA 50601 • (641) 847-2651 *See Reservation Info for Booking Discount details Montana, Glacier National Park & Canadian Rockies by Train Itinerary Day 1: Depart St. Paul - All Aboard Day 7: Banff - The Fort Museum - Waterton - Glacier Nat’l Park Transfer to St. Paul’s Union Depot and board Amtrak’s famous ‘Empire Today travel south and visit The Fort Museum of the North West Mounted Builder’ Train bound for Montana and Glacier National Park. Sit back and Police. The museum welcomes visitors with red-coated students playing the relax as you ride the rails and overnight onboard as the train heads West part of the now defunct NW Mounted Police who became the core of today’s through Minnesota, North Dakota and Montana. -

Couples Therapy at Ocean Coral Creating Happy Healthy Relationships One Couple at a Time

Couples Therapy at Ocean Coral Creating Happy Healthy Relationships One couple at a time The Recommended Resort List Award Winning Luxury Hotel Brands • Oetker Collection • Club Med Five Trident Resorts • Six Sense • Auberge Resorts • Rosewood Hotels & Resorts • Montage Hotels & Resorts • Four Season Hotels & Resorts • Belmond Hotels & Resorts • Aman Hotels & Resorts • Fairmont Hotels & Resorts Recommended All-Inclusive Resort Brands • Club Med Resorts • Marriott All-Inclusive Resorts • Blue Diamond Resorts • Playa Hotel & Resorts • AIC Hotel Group (Hard Rock, Nobu, Unico) • Pallladium Resorts • The Excellence Collection • RIU Resorts • Velas Resorts • Barcelo Resorts • Iberostar Resorts • Palace Resorts • AMResorts (Secrets, Dreams, Zoetry, Breathless) • Karisma Resorts Resource Articles 1 • Travel + Leisure – The top 25 resort hotels in the Caribbean, Bermuda & Bahamas • Travel & Leisure – The top 10 resort hotels in Mexico • Conde Nast Traveller – Readers’ choice awards • Conde Nast Traveller – The gold list • Travel + Leisure - Best affordable all-inclusive resorts • The 14 best bang for your buck all-inclusive resorts Award Winning Hotels & Resorts* *According to Condé Nast Travel, Travel + Leisure, Forbes, etc. The Caribbean Anguila • The Reef Resort Antigua & Barbuda • Elite Island Resorts (value & 5 options) • Curtain Bluff Resort & Spa • Jumby Bay Island Resort & Spa • Carlisle Bay Resort Bahamas • Club Med Columbus Isle (value) • Kamalame Cay Resort • The Cove Atlantis • Atlantis Paradise Island Barbados • The Club Barbados -

NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM B

NFS Fbnn 10-900 'Oitntf* 024-0019 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service I * II b 1995 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM iNTERAGENCY RBOr- „ NATIONAL i3AR: 1. Name of Property fe NAllUNAL HhblbiLH d»vu,su historic name: Glacier National Park Tourist Trails: Inside Trail; South Circle; North Circle other name/site number Glacier National Park Circle Trails 2. Location street & number N/A not for publication: n/a vicinity: Glacier National Park (GLAC) city/town: N/A state: Montana code: MT county: Flathead; Glacier code: 29; 35 zip code: 59938 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1988, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally X statewide _ locally. ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) ) 9. STgnatuTBof 'certifying official/Title National Park Service State or Federal agency or bureau In my opinion, thejiuipKty. does not meet the National Register criteria. gj-^ 1B> 2 9 1995. Signature of commenting or other o Date Montana State Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service -

Viad Corp (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 36-1169950 State Or Other Jurisdiction of (I.R.S

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017 or TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ____________ to ____________ Commission file number: 001-11015 Viad Corp (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 36-1169950 State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization Identification No.) 1850 North Central Avenue, Suite 1900 Phoenix, Arizona 85004-4565 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (602) 207-1000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered Common Stock, $1.50 par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined by Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Geochemical Evidence of Anthropogenic Impacts on Swiftcurrent Lake, Glacier National Park, Mt

KECK GEOLOGY CONSORTIUM PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL KECK RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM IN GEOLOGY April 2011 Union College, Schenectady, NY Dr. Robert J. Varga, Editor Director, Keck Geology Consortium Pomona College Dr. Holli Frey Symposium Convenor Union College Carol Morgan Keck Geology Consortium Administrative Assistant Diane Kadyk Symposium Proceedings Layout & Design Department of Earth & Environment Franklin & Marshall College Keck Geology Consortium Geology Department, Pomona College 185 E. 6th St., Claremont, CA 91711 (909) 607-0651, [email protected], keckgeology.org ISSN# 1528-7491 The Consortium Colleges The National Science Foundation ExxonMobil Corporation KECK GEOLOGY CONSORTIUM PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL KECK RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM IN GEOLOGY ISSN# 1528-7491 April 2011 Robert J. Varga Keck Geology Consortium Diane Kadyk Editor and Keck Director Pomona College Proceedings Layout & Design Pomona College 185 E 6th St., Claremont, CA Franklin & Marshall College 91711 Keck Geology Consortium Member Institutions: Amherst College, Beloit College, Carleton College, Colgate University, The College of Wooster, The Colorado College, Franklin & Marshall College, Macalester College, Mt Holyoke College, Oberlin College, Pomona College, Smith College, Trinity University, Union College, Washington & Lee University, Wesleyan University, Whitman College, Williams College 2010-2011 PROJECTS FORMATION OF BASEMENT-INVOLVED FORELAND ARCHES: INTEGRATED STRUCTURAL AND SEISMOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN THE BIGHORN MOUNTAINS, WYOMING Faculty: CHRISTINE SIDDOWAY, MEGAN ANDERSON, Colorado College, ERIC ERSLEV, University of Wyoming Students: MOLLY CHAMBERLIN, Texas A&M University, ELIZABETH DALLEY, Oberlin College, JOHN SPENCE HORNBUCKLE III, Washington and Lee University, BRYAN MCATEE, Lafayette College, DAVID OAKLEY, Williams College, DREW C. THAYER, Colorado College, CHAD TREXLER, Whitman College, TRIANA N. UFRET, University of Puerto Rico, BRENNAN YOUNG, Utah State University. -

Fire Frequency During the Last Millennium in the Grinnell Glacier and Swiftcurrent Valley Drainage Basins, Glacier National Park, Montana

Fire Frequency During the Last Millennium in the Grinnell Glacier and Swiftcurrent Valley Drainage Basins, Glacier National Park, Montana A Senior Thesis presented to The Faculty of the Department of Geology Bachelor of Arts Madison Evans Andres The Colorado College May 2015 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements iv Abstract v Chapter 1-Introduction 1 Chapter 2-Previous Work 5 Fire as an Earth System Process 5 Fire Records 6 Fire in the northern Rocky Mountain region 7 Fire in Glacier National Park 9 Chapter 3-Study Area 11 Chapter 4-Methods 15 Field Methods 15 Laboratory Methods 15 Initial Core Descriptions 15 Charcoal Methods 16 Dating Techniques 17 Chapter 5-Results 20 Lithology 20 Chronology 20 Charcoal Results 21 Chapter 6-Discussion and Conclusions 27 References 34 Appendices Appendix 1: Initial Core Description Sheets 37 Appendix 2: Charcoal Count Sheets 40 ii List of Figures Figure 1: Geologic map of the Many Glacier region 3 Figure 2: Primary and secondary charcoal schematic diagram 8 Figure 3: Bathymetric data for Swiftcurrent Lake with core locations 10 Figure 4: Image of 3 drainage basins for Swiftcurrent Lake 13 Figure 5: Swiftcurrent lithologic results 22 Figure 6: Loss-on-ignition organic carbon comparison 24 Figure 7: Age-to-depth model based on LOI comparison 25 Figure 8: CHAR rates for ~1700 year record 25 Figure 9: Fire frequency for ~1700 year record 32 List of Tables Table 1: Monthly climate summary for Glacier National Park, MT 13 Table 2: Average annual visitation rate for Glacier National Park, MT 13 Table 3: Parameter file input for CharAnalysis computer program 19 Table 4: Comparison of factors contributing to CHAR rates 32 iii Acknowledgements It is important to acknowledge the incredible support that I have received throughout this yearlong process.