Aviation Occurrence Statistics 2002 to 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aviation in the Pacific International Aviation Services Are Crucial to Trade, Growth, and Development in the Pacific Region

Pacific Studies Series About Oceanic Voyages: Aviation in the Pacific International aviation services are crucial to trade, growth, and development in the Pacific region. Improved access provided by international aviation from every other region in the world to an increasing number of islands is opening new opportunities. Tourism contributes substantially to income and employment in many Pacific countries, usually in areas outside of the main urban centers, and enables air freight services for valuable but perishable commodities that would otherwise not be marketable. Although some features of the Pacific region make provision of international aviation services a challenge, there have also been some notable successes that offer key lessons for future development. Case studies of national aviation sector experience show the value of operating on commercial principles, attracting international and OCEANIC V private-sector capital investment, assigning risk where it can best be managed, and liberalizing market access. Integration of the regional market for transport services, combined with harmonized but less restrictive regulations, would facilitate a greater range of services at more competitive prices. Pacific island country governments have the ability to create effective operating environments. When they do so, experience O shows that operators will respond with efficient service provision. YAGES: About the Asian Development Bank Av ADB aims to improve the welfare of the people in the Asia and Pacific region, IATI particularly the nearly 1.9 billion who live on less than $2 a day. Despite many success stories, the region remains home to two thirds of the world’s poor. ADB is O N IN THE PACIFIC a multilateral development finance institution owned by 67 members, 48 from the region and 19 from other parts of the globe. -

Regulamento (Ue) N

11.2.2012 PT Jornal Oficial da União Europeia L 39/1 II (Atos não legislativos) REGULAMENTOS o REGULAMENTO (UE) N. 100/2012 DA COMISSÃO de 3 de fevereiro de 2012 o que altera o Regulamento (CE) n. 748/2009, relativo à lista de operadores de aeronaves que realizaram uma das atividades de aviação enumeradas no anexo I da Diretiva 2003/87/CE em ou após 1 de janeiro de 2006, inclusive, com indicação do Estado-Membro responsável em relação a cada operador de aeronave, tendo igualmente em conta a expansão do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União aos países EEE-EFTA (Texto relevante para efeitos do EEE) A COMISSÃO EUROPEIA, 2003/87/CE e é independente da inclusão na lista de operadores de aeronaves estabelecida pela Comissão por o o força do artigo 18. -A, n. 3, da diretiva. Tendo em conta o Tratado sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia, (5) A Diretiva 2008/101/CE foi incorporada no Acordo so bre o Espaço Económico Europeu pela Decisão o Tendo em conta a Diretiva 2003/87/CE do Parlamento Europeu n. 6/2011 do Comité Misto do EEE, de 1 de abril de e do Conselho, de 13 de Outubro de 2003, relativa à criação de 2011, que altera o anexo XX (Ambiente) do Acordo um regime de comércio de licenças de emissão de gases com EEE ( 4). efeito de estufa na Comunidade e que altera a Diretiva 96/61/CE o o do Conselho ( 1), nomeadamente o artigo 18. -A, n. 3, alínea a), (6) A extensão das disposições do regime de comércio de licenças de emissão da União, no setor da aviação, aos Considerando o seguinte: países EEE-EFTA implica que os critérios fixados nos o o termos do artigo 18. -

Rozporządzenia

6.2.2014 PL Dziennik Urzędowy Unii Europejskiej L 37/1 II (Akty o charakterze nieustawodawczym) ROZPORZĄDZENIA ROZPORZĄDZENIE KOMISJI (UE) NR 100/2014 z dnia 5 lutego 2014 r. zmieniające rozporządzenie (WE) nr 748/2009 w sprawie wykazu operatorów statków powietrznych, którzy wykonywali działalność lotniczą wymienioną w załączniku I do dyrektywy 2003/87/WE Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady poczynając od dnia 1 stycznia 2006 r. ze wskazaniem administrującego państwa członkowskiego dla każdego operatora statków powietrznych (Tekst mający znaczenie dla EOG) KOMISJA EUROPEJSKA, (3) Celem tego wykazu jest zmniejszenie obciążenia admi nistracyjnego ponoszonego przez operatorów statków powietrznych poprzez udostępnienie informacji o tym, które z państw członkowskich jest regulatorem danego uwzględniając Traktat o funkcjonowaniu Unii Europejskiej, operatora statków powietrznych. (4) Objęcie operatora statków powietrznych unijnym uwzględniając dyrektywę 2003/87/WE Parlamentu Europej systemem handlu uprawnieniami do emisji gazów skiego i Rady z dnia 13 października 2003 r. ustanawiającą cieplarnianych uzależnione jest od wykonywania działal system handlu przydziałami emisji gazów cieplarnianych we ności lotniczej wymienionej w załączniku I do dyrektywy Wspólnocie oraz zmieniającą dyrektywę Rady 96/61/WE ( 1), 2003/87/WE, nie jest natomiast uzależnione od umiesz w szczególności jej art. 18a ust. 3 lit. b), czenia danego operatora w wykazie operatorów statków powietrznych ustanowionym przez Komisję na podstawie art. 18a ust. 3 wspomnianej dyrektywy. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Defendants European Aviation, Ltd. and European Skybus Ltd

-CHE Capital Airline Engine Leasing LLC v. European Aviation Air Charter Ltd et al Doc. 19 E-FILED Monday, 18 October, 2010 10:08:43 AM Clerk, U.S. District Court, ILCD IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE CENTRAL DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS SPRINGFIELD DIVISION CAPITAL AIRLINE ENGINE ) LEASING, LLC., ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 10-3105 ) EUROPEAN AVIATION AIR ) CHARTER LTD., EUROPEAN ) AVIATION, LTD., and ) EUROPEAN SKYBUS LTD., ) ) Defendants. ) OPINION This matter comes before the Court on Defendants European Aviation, Ltd. (Aviation) and European Skybus Ltd.’s (Skybus) Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff’s Complaint (d/e 13). For the reasons set forth below, the Motion is ALLOWED in part and DENIED in part. The claims against Aviation are dismissed for lack of jurisdiction, but Skybus’ Motion to Dismiss is denied. STATEMENT OF FACTS Aviation and Skybus move to dismiss for failure to state a claim and for lack of personal jurisdiction. For purposes of the Motion to Dismiss for failure to state a claim, the Court must accept as true all well-pleaded factual allegations contained in the Complaint (d/e 1) and draw all inferences in the light most favorable to Plaintiff Capital Airline Engine Leasing, LLC (Capital). Hager v. City of West Peoria, 84 F.3d 1 Dockets.Justia.com 865, 868-69 (7th Cir. 1996); Covington Court, Ltd. v. Village of Oak Brook, 77 F.3d 177, 178 (7th Cir. 1996). For purposes of the Motion to Dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction, the Court must accept the jurisdictional allegations in the Complaint because Aviation and Skybus have not submitted any contravening affidavits. -

27.4.2011 Journal Officiel De L'union Européenne L 107/3

27.4.2011 FR Journal officiel de l’Union européenne L 107/3 ANNEXE Liste des exploitants d'aéronefs ayant exercé une activité aérienne visée à l’annexe I de la directive 2003/87/CE à compter du 1 er janvier 2006 et précisant l’État membre de l'EEE responsable de chaque exploitant d’aéronefs BELGIQUE SCRR Numéro Nom de l’exploitant État de l'exploitant d'identification 123 Abelag Aviation BELGIQUE 7649 AIRBORNE EXPRESS ÉTATS-UNIS 33612 ALLIED AIR LIMITED NIGERIA 30020 AVIASTAR-TU CO. RUSSIE 31416 AVIA TRAFFIC COMPANY RUSSIE 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIQUE 25996 CAIRO AVIATION ÉGYPTE 4369 CAL CARGO AIRLINES ISRAËL 29517 CAPITAL AVTN SRVCS PAYS-BAS 36867 CLASSIC JET HERITAGE ROYAUME-UNI 36515 CONTRAIL AVIATION ÉTATS-UNIS f11336 CORPORATE WINGS LLC ÉTATS-UNIS 32909 CRESAIR INC ÉTATS-UNIS 985 EAT BELGIQUE 32432 EGYPTAIR CARGO ÉGYPTE 36012 ENJOY AIR SUISSE f11102 FedEx Express Corporate Aviation ÉTATS-UNIS f11256 Flying Partners CVBA BELGIQUE 13457 Flying Service N.V. BELGIQUE 32486 FAYARD ENTERPRISES ÉTATS-UNIS 24578 GAFI GENERAL AVIAT SUISSE 32737 GREAT ALLIANCE WORLD ROYAUME-UNI 29980 HAINAN AIRLINES (2) CHINE 23700 HEWA BORA AIRWAYS CONGO 28582 INTER-WETALL SUISSE 9542 INTL PAPER CY ÉTATS-UNIS 27709 KALITTA AIR ÉTATS-UNIS 28087 LAS VEGAS CHARTER ÉTATS-UNIS 32303 MASTER TOP LINHAS BRÉSIL 37066 MERIDIAN (AIRWAYS) BELGIQUE 1084 MIL BELGIUM BELGIQUE 31565 MONTE CARLO AVTN BELGIQUE 26688 NEWELL RUBBERMAID ÉTATS-UNIS f11805 NUCOR CORP ÉTATS-UNIS 31207 N604FJ LLC ÉTATS-UNIS f11462 N907WS AVIATION LLC ÉTATS-UNIS f10341 OfficeMax Inc ÉTATS-UNIS 36214 -

The Table of Services (PDF)

APPENDIX 1: TABLE OF SERVICES Proposed Service Contract type Availability Brief Service Description Airframe Aircraft Type Nominated Operational Base Firebombing Delivery System Passenger Carriage Fuelling Service Period Approximate timing Specimen Contract applicable Schedules Additional Information ID Primary / Absolute / Partial RW / FW Type 1 / Type 2 / Type 3 Tank / Bucket / (Bucket) / Long line bucket / Tank or Required / Optional Wet-A Hire / Wet- (in addition to Schedules 1, 2, 3,4, & 5) Secondary bucket / Tank (preferred) or Bucket B Hire / Dry Hire (Note 7) (Note 11) (Note 1) (Note 2) (Note 5) (Note 9) (Note 10) (Note 3) (Note 4) (Note 4) (Note 6) (Note 8) AAS Firefighter & Cargo Transport RW21302 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Moorabbin Airport, Victoria Bucket (Optional) Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules A & B Burning (Note 14) Firebombing (optional) AAS Firefighter & Cargo Transport RW21303 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Ovens helibase, Victoria (Note A) Bucket Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules A & B Firebombing Burning (Note 14) AAS Firefighter & Cargo Transport RW21304 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Bairnsdale, Victoria Bucket Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules A & B Firebombing Burning (Note 14) AAS RW21305 Primary Absolute ROTARY WING Type 3 Bendigo Airport, Victoria (Bucket) Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules B Burning (preferred) (Note 14) Airborne Information Gathering (AIG) (Note 16) This Service requires a specific configuration to support regular 'airborne information gathering' operations (Refer to Section 2.1 of Part B RW21307 Primary Absolute AAS ROTARY WING Type 3 Moorabbin Airport, Victoria (Bucket) Required Wet-B 14 weeks Dec-Mar Schedules B & C in the Invitation to Tender document). -

Prior Compliance List of Aircraft Operators Specifying the Administering Member State for Each Aircraft Operator – June 2014

Prior compliance list of aircraft operators specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator – June 2014 Inclusion in the prior compliance list allows aircraft operators to know which Member State will most likely be attributed to them as their administering Member State so they can get in contact with the competent authority of that Member State to discuss the requirements and the next steps. Due to a number of reasons, and especially because a number of aircraft operators use services of management companies, some of those operators have not been identified in the latest update of the EEA- wide list of aircraft operators adopted on 5 February 2014. The present version of the prior compliance list includes those aircraft operators, which have submitted their fleet lists between December 2013 and January 2014. BELGIUM CRCO Identification no. Operator Name State of the Operator 31102 ACT AIRLINES TURKEY 7649 AIRBORNE EXPRESS UNITED STATES 33612 ALLIED AIR LIMITED NIGERIA 29424 ASTRAL AVIATION LTD KENYA 31416 AVIA TRAFFIC COMPANY TAJIKISTAN 30020 AVIASTAR-TU CO. RUSSIAN FEDERATION 40259 BRAVO CARGO UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM 25996 CAIRO AVIATION EGYPT 4369 CAL CARGO AIRLINES ISRAEL 29517 CAPITAL AVTN SRVCS NETHERLANDS 39758 CHALLENGER AERO PHILIPPINES f11336 CORPORATE WINGS LLC UNITED STATES 32909 CRESAIR INC UNITED STATES 32432 EGYPTAIR CARGO EGYPT f12977 EXCELLENT INVESTMENT UNITED STATES LLC 32486 FAYARD ENTERPRISES UNITED STATES f11102 FedEx Express Corporate UNITED STATES Aviation 13457 Flying -

16325/09 ADD 1 GW/Ay 1 DG C III COUNCIL of the EUROPEAN

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 19 November 2009 THE EUROPEAN UNION 16325/09 ADD 1 AVIATION 191 COVER NOTE from: Secretary-General of the European Commission, signed by Mr Jordi AYET PUIGARNAU, Director date of receipt: 18 November 2009 to: Mr Javier SOLANA, Secretary-General/High Representative Subject: Commission staff working document accompanying the report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council European Community SAFA Programme Aggregated information report (01 january 2008 to 31 december 2008) Delegations will find attached Commission document SEC(2009) 1576 final. ________________________ Encl.: SEC(2009) 1576 final 16325/09 ADD 1 GW/ay 1 DG C III EN COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 18.11.2009 SEC(2009) 1576 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT accompanying the REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL EUROPEAN COMMUNITY SAFA PROGRAMME AGGREGATED INFORMATION REPORT (01 January 2008 to 31 December 2008) [COM(2009) 627 final] EN EN COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT AGGREGATED INFORMATION REPORT (01 January 2008 to 31 December 2008) Appendix A – Data Collection by SAFA Programme Participating States (January-December 2008) EU Member States No. No. Average no. of inspected No. Member State Inspections Findings items/inspection 1 Austria 310 429 41.37 2 Belgium 113 125 28.25 29.60 3 Bulgaria 10 18 4 Cyprus 20 11 42.50 5 Czech Republic 29 19 32.00 6 Denmark 60 16 39.60 7 Estonia 0 0 0 8 Finland 120 95 41.93 9 France 2,594 3,572 33.61 10 Germany 1,152 1,012 40.80 11 Greece 974 103 18.85 12 Hungary 7 9 26.57 13 Ireland 25 10 48.80 14 Italy 873 820 31.42 15 Latvia 30 34 30.20 16 Lithuania 12 9 48.08 17 Luxembourg 26 24 29.08 18 Malta 13 6 36.54 19 Netherlands 258 819 36.91 EN 2 EN 20 Poland 227 34 39.59 21 Portugal 53 98 46.51 22 Romania 171 80 28.37 23 Slovak Republic 13 5 23.69 24 Slovenia 19 8 27.00 25 Spain 1,230 2,227 39.51 26 Sweden 91 120 44.81 27 United Kingdom 610 445 39.65 Total 9,040 10,148 34.63 Non-EU ECAC SAFA Participating States No. -

2010-11 Victorian Floods Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment Project

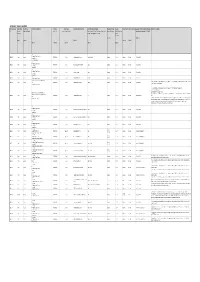

Review by: 2010-11 Victorian Floods Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment Project December 2012 ISO 9001 QEC22878 SAI Global Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010-11 Victorian Floods – Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment DOCUMENT STATUS Version Doc type Reviewed by Approved by Date issued v01 Report Warwick Bishop 02/06/2012 v02 Report Michael Cawood Warwick Bishop 07/11/2012 FINAL Report Ben Tate Ben Tate 07/12/2012 PROJECT DETAILS 2010-11 Victorian Floods – Rainfall and Streamflow Project Name Assessment Client Department of Sustainability and Environment Client Project Manager Simone Wilkinson Water Technology Project Manager Ben Tate Report Authors Ben Tate Job Number 2106-01 Report Number R02 Document Name 2106R02_FINAL_2010-11_VIC_Floods.docx Cover Photo: Flooding near Kerang in January 2011 (source: www.weeklytimesnow.com.au). Copyright Water Technology Pty Ltd has produced this document in accordance with instructions from Department of Sustainability and Environment for their use only. The concepts and information contained in this document are the copyright of Water Technology Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without written permission of Water Technology Pty Ltd constitutes an infringement of copyright. Water Technology Pty Ltd does not warrant this document is definitive nor free from error and does not accept liability for any loss caused, or arising from, reliance upon the information provided herein. 15 Business Park Drive Notting Hill VIC 3168 Telephone (03) 9558 9366 Fax (03) 9558 9365 ACN No. 093 377 283 ABN No. 60 093 377 283 2106-01 / R02 FINAL - 07/12/2012 ii Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010-11 Victorian Floods – Rainfall and Streamflow Assessment GLOSSARY Annual Exceedance Refers to the probability or risk of a flood of a given size occurring or being exceeded in any given year. -

Amount Committed Funding Allocated So Far 2019/20 2020/21 TOTAL

Amount Committed Funding allocated so far 2019/20 2020/21 TOTAL Eligibility requirements (if any) Allocated Paid amount Remaining funds Notes Australian Airline Financial Relief Package $437 million $278 million $715 The scheme is open to all organisations with an Air Operator’s $504.9 million $292.3 million $210.1 million $400 million waiver of Airservices (AAFRP) million Certificate authorising: *at 2 June 2020 *total committed less total Australia (Airservices) charges (paid unallocated in advance to Airservices Australia to Announced on 18 March. The purpose of domestic scheduled RPT services, enable fees to be waived and the grant program is to assist the domestic domestic commercial charter operations, services to continue), airline industry in response to the economic aerial agriculture, aerial work and flight training, or $173 million value to industry of pressures created by the impact of COVID-19 contracted aeromedical service. domestic aviation security charges by reducing operational cost pressures to $20 million value to industry for Organisations must also: improve the ability to maintain services. The enhanced regional security screening have an Australian Business Number (ABN) program will end on 30 September 2020. costs, be registered for the purposes of GST $46 million infrastructure support Eligible operators who have applied and have an account with an Australian financial institution for regional airport operators to been approved funding under the program be one of the following entity types: implement enhanced regional are provided at Attachment A. o a company incorporated in Australia aviation security requirements, and o a company incorporated by guarantee $46 million value to industry of o Figures as at 2 June 2020. -

Airliner Census Western-Built Jet and Turboprop Airliners

World airliner census Western-built jet and turboprop airliners AEROSPATIALE (NORD) 262 7 Lufthansa (600R) 2 Biman Bangladesh Airlines (300) 4 Tarom (300) 2 Africa 3 MNG Airlines (B4) 2 China Eastern Airlines (200) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (200) 1 Equatorial Int’l Airlines (A) 1 MNG Airlines (B4 Freighter) 5 Emirates (300) 1 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300) 5 Int’l Trans Air Business (A) 1 MNG Airlines (F4) 3 Emirates (300F) 3 Turkish Airlines (THY) (300F) 1 Trans Service Airlift (B) 1 Monarch Airlines (600R) 4 Iran Air (200) 6 Uzbekistan Airways (300) 3 North/South America 4 Olympic Airlines (600R) 1 Iran Air (300) 2 White (300) 1 Aerolineas Sosa (A) 3 Onur Air (600R) 6 Iraqi Airways (300) (5) North/South America 81 RACSA (A) 1 Onur Air (B2) 1 Jordan Aviation (200) 1 Aerolineas Argentinas (300) 2 AEROSPATIALE (SUD) CARAVELLE 2 Onur Air (B4) 5 Jordan Aviation (300) 1 Air Transat (300) 11 Europe 2 Pan Air (B4 Freighter) 2 Kuwait Airways (300) 4 FedEx Express (200F) 49 WaltAir (10B) 1 Saga Airlines (B2) 1 Mahan Air (300) 2 FedEx Express (300) 7 WaltAir (11R) 1 TNT Airways (B4 Freighter) 4 Miat Mongolian Airlines (300) 1 FedEx Express (300F) 12 AIRBUS A300 408 (8) North/South America 166 (7) Pakistan Int’l Airlines (300) 12 AIRBUS A318-100 30 (48) Africa 14 Aero Union (B4 Freighter) 4 Royal Jordanian (300) 4 Europe 13 (9) Egyptair (600R) 1 American Airlines (600R) 34 Royal Jordanian (300F) 2 Air France 13 (5) Egyptair (600R Freighter) 1 ASTAR Air Cargo (B4 Freighter) 6 Yemenia (300) 4 Tarom (4) Egyptair (B4 Freighter) 2 Express.net Airlines