Unearthing American Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOM MALONEY and TOM HALL a Tribute to Four Important St

TOM MALONEY AND TOM HALL A Tribute to Four Important St. Louisans, BLUESWEEK Review in Pictures, An Essay by Alonzo Townsend, The Application Window Opens for the St. Louis/IBC Road to Memphis, plus: CD Review, Discounts for Members and more... THE BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE SAINT LOUIS BLUES SOCIETY July/August 2014 Number 69 July/August 2014 Number 69 Officers Chairperson BLUESLETTER John May The Bi-Monthly Magazine of the St. Louis Blues Society Vice Chairperson The St. Louis Blues Society is dedicated to preserving and perpetuating blues music in Jeremy Segel-Moss and from St. Louis, while fostering its growth and appreciation. The St. Louis Blues Society provides blues artists the opportunity for public performance and individual Treasurer improvement in their field, all for the educational and artistic benefit of the general public. Jerry Minchey Legal Counsel Charley Taylor CELEBRATING 30 YEARS Secretary Lynn Barlar OF SUPPORTING BLUES MUSIC IN ST LOUIS Communications Dear Blues Lovers, Mary Kaye Tönnies Summer is in full swing in St. Louis.Festivals, neighborhood events and patios filled with Board of Directors music are kickin’ all over the City. Bluesweek, over Memorial Day Weekend, was a big hit for Ridgley "Hound Dog" Brown musicians and fans alike. Check out some of the pictures from the weekend on page 11. Thanks to Bernie Hayes everyone who helped make Bluesweek a success! Glenn Howard July means the opening of applications for bands and solo/duo acts who want to be involved Rich Hughes in this year’s International Blues Challenge. Last year we had a fantastic group of bands and solo/ Greg Hunt duo acts competing to go to Memphis. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

The Jones Tones Are a Veteran Band of Four Musicians, All with a Distinctive Style and Personality That Blends Into a Powerful Whole

Davey J and the Jones Tones are a veteran band of four musicians, all with a distinctive style and personality that blends into a powerful whole. As bandleader, Davey J's approach to the blues is all about Furry Lewis (by Reverend Keith A. Gordon, About.com Guide) the shuffle, a style and tempo pioneered in acoustic Delta blues and electric Chicago blues. When the four- Bridging the gap between the early acoustic blues of the Mississippi Delta of the 1920s and the rediscovery piece band gets its groove on, you can hear the foot-tapping acoustic-electric sounds from the era of of so-called "folk" or country blues by white audiences in the '60s, Furry Lewis was both a unique stylist and a rockabilly, Nashville country and western, early rock and roll, and of course, classic Chicago blues. And in throwback to the sound of an earlier era. Equally capable of playing guitar with an original fingerpicked style the midst of the traditional shuffle tempos and rich vocals, Davey J also uses processing tools of the 21st as well as delivering a mean slide-guitar sound, Lewis was a charismatic storyteller and a flamboyant century to add an edge to his acoustic guitar sound. So, as the Jones Tones perform songs that range from showman that performed naturally with skill and humor. the 1930s Delta blues to the blues styles of our time, the band pays tribute to blues traditions as well as Born Walter Lewis in Greenwood, Mississippi in the Delta, the exact year of his birth remains in question, and creating an original new sound. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title Title - Be 02 Johnny Cash 03-Martina McBride 05 LeAnn Rimes - Butto Folsom Prison Blues Anyway How Do I Live - Promiscuo 02 Josh Turner 04 Ariana Grande Ft Iggy Azalea 05 Lionel Richie & Diana Ross - TWIST & SHO Why Don't We Just Dance Problem Endless Love (Without Vocals) (Christmas) 02 Lorde 04 Brian McKnight 05 Night Ranger Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer Royals Back At One Sister Christian Karaoke Mix (Kissed You) Good Night 02 Madonna 04 Charlie Rich 05 Odyssey Gloriana Material Girl Behind Closed Doors Native New Yorker (Karaoke) (Kissed You) Good Night Wvocal 02 Mark Ronson Feat.. Bruno Mars 04 Dan Hartman 05 Reba McIntire Gloriana Uptown Funk Relight My Fire (Karaoke) Consider Me Gone 01 98 Degress 02 Ricky Martin 04 Goo Goo Dolls 05 Taylor Swift Becouse Of You Livin' La Vida Loca (Dance Mix) Slide (Dance Mix) Blank Space 01 Bob Seger 02 Robin Thicke 04 Heart 05 The B-52's Hollywood Nights Blurred Lines Never Love Shack 01 Bob Wills And His Texas 02 Sam Smith 04 Imagine Dragons 05-Martina McBride Playboys Stay With Me Radioactive Happy Girl Faded Love 02 Taylor Swift 04 Jason Aldean 06 Alanis Morissette 01 Celine Dion You Belong With Me Big Green Tractor Uninvited (Dance Mix) My Heart Will Go On 02 The Police 04 Kellie Pickler 06 Avicci 01 Christina Aguilera Every Breath You Take Best Days Of Your Life Wake Me Up Genie In A Bottle (Dance Mix) 02 Village People, The 04 Kenny Rogers & First Edition 06 Bette Midler 01 Corey Hart YMCA (Karaoke) Lucille The Rose Karaoke Mix Sunglasses At Night Karaoke Mix 02 Whitney Houston 04 Kim Carnes 06 Black Sabbath 01 Deborah Cox How Will I Know Karaoke Mix Bette Davis Eyes Karaoke Mix Paranoid Nobody's Supposed To Be Here 02-Martina McBride 04 Mariah Carey 06 Chic 01 Gloria Gaynor A Broken Wing I Still Believe Dance Dance Dance (Karaoke) I Will Survive (Karaoke) 03 Billy Currington 04 Maroon 5 06 Conway Twitty 01 Hank Williams Jr People Are Crazy Animals I`d Love To Lay You Down Family Tradition 03 Britney Spears 04 No Doubt 06 Fall Out Boy 01 Iggy Azalea Feat. -

Prairie Progressive • Spring 2015

THE PRAIRIE PROGRESSIVE Spring 2015 A NEWSLETTER FOR IOWA’S DEMOCRATIC LEFT Cousins, Clerics, and the Constitution hen the current Constitution of the Equal Protection clauses of the familial status of such person.” This the State of Iowa was debated United States and Iowa Constitutions is directly quoted from Iowa’s Civil Wand adopted in 1857, the first days as it pertains to zoning. Rights Statute. of the convention were rife with arguments of moving the convention Two bills are moving in the Iowa Leg- It has been difficult to get legislators from Iowa City because of the lack islature this year. House File 161 is a to listen to the argument that the of housing. Out-of-towners thought bill in the House of Representatives Ames Rental lawsuit is not the final the price of accommodations in Iowa that prohibits the regulation of rental word on this matter. The lawsuit City were not fair. Besides, as one property by a city based upon famil- was brought by landlords and they delegate stated, “Half of the members ial relationships. It has a partner in sued the city in the only way they of the Convention have to sleep three the Iowa Senate – Senate Study Bill could. Landlords could not use the in a bed, and two on a bunk.” 1218 (which will have a new name Civil Rights Statute to bring a law- and number after Prairie Dog sends suit because they would not have The cost of accommodations in Iowa this out to readers). The bills were standing (standing, or locus standi, City may still be steep, especially on identical at their inception, but SSB is the requirement that a plaintiff has weekends during the fall months, 1218 has been amended in Committee sustained or will sustain direct injury but otherwise, things have changed. -

Samuel B. Charters: Notes to Folkways FS 3823 "Furry Lewis"

FOLKWAYS RECORDS Album No. FA 3823 ©1959 Folkways Records & Service Corp., 43 W. 61st St., N. Y. C., USA FURRY LEWIS Edited by Samuel B. Charters Photo by A. R. Danberg FURRY LEWIS imagination that doesn't depend on technical display. As the singers mature their music often The last time I saw Furry Lewis he was chopping weeds achieves a new expressiveness. on a highway embankment near the outskirts of Memphis, Tennessee, the town he has lived in since he was six years- old. He was wearing faded denim overalls, a khaki work shirt, a bright red handkerchief tied The next afternoon I rented a guitar, a big Epiphone, around his neck. It was a hot day, and his sweat from a pawn shop on Beale Street, and took it over soaked shirt clung to his back. He was chopping at to Furry's room. He had gotten off work early and the heavy plants with a hoe, stopping every now and was sitting on the porch waiting for me. He carried then to wipe off his face. Furry has worked as a the guitar inside, sat down and strummed the strings laborer for the city of Memphis for nearly thirty- to make sure it was in tune, then looked up and five years. He chops weeds, cuts grass, rakes leaves, asked me, "What would you like to hear? " picks up trash, whatever needs done around the city's streets and parks. He limps a little, but watching I was surprised that he didn't want to try the him work it's still a surprise to notice that he has guitar a little first, but I managed to think of only one leg. -

May 22-28 2014

MAY 22-28 2014 BROADWAY AT THE EMBASSY October 20, 2014 October 20, 2014 RETURNING BY POPULAR DEMAND 13 & 14, November, January 25, 2015 January 25, Photos by Jeremy Daniel February 25, 2015 25, February FORT WAYNE PREMIERE April 14 - 19, 2015 Subscribe To The 2014 - 15 Season Today 260.424.5665 | FWEmbassyTheatre.org 2015 March 25, 2 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- www.whatzup.com -----------------------------------------------------------------May 22, 2014 whatzup Proudly presents in Fort Wayne, Indiana Volume 18, Number 41 ON SALE THIS f you’re looking for something to do in the Fort Wayne area this week or MAYFRIDAY! 23 ! next, you’ve come to the right place. We’re in our 18th year of telling Fort Wayne area residents where to go – or whatzup, to put it more mildly. RegularI readers already know that this is where to go if you want to find every- thing there is to do – music, theatre, art, what have you – all in one place. If you’re new to whatzup, we invite you to spend some time reading this publica- tion’s features, calendars, columns and ads. We’re pretty sure you’re going to find something you don’t want to miss. A print product such as this has one serious limitation: space. So if you’re looking for something to do in, say, a month or two from now, check out our website at www.whatzup.com. If we have it in our system (and we work hard at making sure we do), you’re going to find it there. And whether at your Thursday August 21, 2014 • 7:30 pm computer or on your smartphone, you’re going to find our website more com- The FoellingerFree Movies Theatre • Fort Wayne, Indiana Tickets The Nut Job Wed June 15 9:00 pm prehensive and easily navigated than any other art and entertainment or news On-line By Phone Surly, a curmudgeon, independent squirrel is banished from his www.foellingertheatre.org (260) 427-6000 park andOn forced to survive Sale in the city. -

Tennessee Blues and Gospel: from Jug Band to Jubilee by David Evans and Richard M

Tennessee Blues and Gospel: From Jug Band to Jubilee by David Evans and Richard M. Raichelson Richard M Raichelson received his doctorate in folklore from the University ofPennsylvania . He has done extensive research on jazz, blues, Sacred and secular Black music traditions have existed side-by and gospel music and has taught in the De side in Tennessee since the arrival of large numbers of slaves to Mis partment ofAnthropology at Memphis State sissippi River lowland plantations in the early 19th century. Although University. church-oriented music has remained separate from entertainment David Evans is a professor ofmusic at and work-related musics in performance, meaning and genre, it has Memphis State University where he specializes in blues. An accomplished guitaris~ he is a pro influenced and, in turn, been influenced by them over time. Many ducer for High Water Records, a recording well-known blues performers have "gone to God," and an equally company devoted to Southern blues and gospel music. large number of religious performers are attentive to the style, if not the ideology, of blues. By far the most important Black secular folk music in Tennessee has been the blues. In the early years of this century, folk blues singers were probably active in every Black community in the state. Memphis was the largest of these and became the place where blues music first gained popularity. W C. Handy, who led a Black orches tra that played the popular tunes of the day for Anglo- and Afro American audiences, published his "Memphis Blues" in 1912, following it with many more blues "hits" in the next few years. -

Page 1 February 2016 Edition by Song Title #Icanteven (I Can't Even)

PAGE 1 FEBRUARY 2016 EDITION BY SONG TITLE #ICANTEVEN (I 31837 THE NEIGHBOURHOOD 187 VS FELIX (V) 30961 BOOTLEG CAN'T EVEN) (V) FT FRENCH MONTANA 19 YOU + ME (V) 27215 DAN & SHAY #SELFIE (V) 27946 THE CHAINSMOKERS 1901 (V) 23066 BIRDY $100 BILL (EXPLICIT) (V) 26811 JAY-Z 19-2000 (V) 24095 GORILLAZ (DON'T FEAR) THE REAPER BLUE OYSTER CULT (7 INCH EDIT) (V) 30394 1959 (V) 16532 LEE KERNAGHAN 1973 12579 JAMES BLUNT (I'D BE) A LEGEND RONNIE MILSAP IN MY TIME (V) 31396 1979 (V) 19860 SMASHING PUMPKINS (IF PARADISE IS) AMEN CORNER 1982 (V) 28398 RANDY TRAVIS HALF AS NICE (V) 32025 1983 (NINETEEN 21305 NEON TREES (WIN, PLACE OR SHOW) INTRUDERS EIGHTY THREE) (V) SHE'S A WINNER (V) 32232 1984 (V) 29718 DAVID BOWIE (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY BRITNEY SPEARS (ALBUM VERSION) (V) 31784 1985 (V) 2222 BOWLING FOR SOUP 1994 (V) 25845 JASON ALDEAN (YOU MAKE ME FEEL LIKE) 31218 ARETHA FRANKLIN A NATURAL WOMAN (V) 1999 8496 PRINCE MARTIN SOLVEIG 1999 (EXTENDED VERSION) PRINCE +1 (V) 32224 FT SAM WHITE 4347 19TH NERVOUS 0 TO 100 - THE CATCH DRAKE 9087 THE ROLLING STONES UP (EXPLICIT) (V) 30044 BREAKDOWN DESMOND DEKKER 1-LUV 6733 E-40 007 12105 & THE ACES 1ST MAN IN SPACE 23233 ALL SEEING I 1 - 2 - 3 (V) 20677 LEN BARRY (FIRST) (V) BONE THUGS N 1 2 3 O'LEARY (V) 17028 DES O'CONNOR 1ST OF THA MONTH 6874 HARMONY 1 TRAIN (V) 30741 A$AP ROCKY 2 BAD 6696 MICHAEL JACKSON 1, 2 STEP (V) 2181 CIARA FT MISSY ELLIOTT 2 BECOME 1 7451 SPICE GIRLS 1, 2, 3, 4 (SUMPIN' NEW) 7051 COOLIO 2 DOORS DOWN 13629 MYSTERY JETS 1, 2, 3, 4 (V) 3778 PLAIN WHITE T'S 2 HEARTS 12951 KYLIE MINOGUE -

Voluptuous Veils, Vigorous Voyage (Part IV)

Voluptuous Veils, Vigorous Voyage (Part IV) A Muddy Boots Production Sound Painting by Tenali Hrenak Going where sneakers never will… Overview Oh how fair these days flickering in lustrous bounty of poetry, story, and song. Come hither and lift up thine ears of rapturous wonder as thunderous waves toucheth thy soul. Host Bedazzled Tenali vows to keepth the tunes aplenty and the verses immense...For nay hardship ne'er snoweth when blows such joys of heavenly sound that cometh from herein and hereout. For archives + info, please check out muddybootsradio.org I’d be honored if you subscribed + left a rating/review on iTunes Track List A Side 1. Escar Morgan's All American One Man Band - Ho-Bo Jo Who Said I Was A Bum Vol 1 2. Miriam Makeba - Umhome Miriam Makeba/The World Of Miriam Makeba 3. Chubby Parker & His Little Old-Time Banjo - The Year Of Jubilo Joe Bussard Presents: The Year Of Jubilo - 78 RPM Recordings Of Songs From The Civil War 4. Minnie Wallace - Dirty Butter Memphis Jug Band with Gus Cannon's Jug Stompers Disc 2 5. Heron - Sally Goodin Upon Reflection: The Dawn Anthology 6. Allison's Sacred Harp Singers - Jewett Sacred Harp & Shape Note 7. Roza Eskenazi - Gazel Hiouzam Women Of Rembetika Vol. 1 8. Sexteto Nacional - Mujeres Enamórenme The Music Of Cuba 1909 - 1951 9. Rudy Sooter and the Horse Opera Company - Up the Alley With Sally Radio & Recording Rarities, Volume 1 10. Oidupaa Vladimir Oiun - Ah, You, Sweetie Divine music from the jail 11. The Incredible String Band - Red Hair Liquid Acrobat As Regards The Air 12. -

'Cause Momma Does It Best

Only Slightly More Offensive Than Cable November 2009 FREE! Vol. 1 - Issue 8 In this month’s issue... Check out our interview with Old Crow Medicine Show! Before (On Left) After Shana McCoy’s Makeover see more pics on page 11 The Best of Paducah O Vote On Your O Favorite Spots Around Town Freezor Pop Fest Come The Show You Don’t Wanna Miss! Win A Date With Bella! Get You Some... See Page 7 For Details ‘Cause Momma Does It Best! OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO 2 2 - Editor’s Note Shana McCoy’s Makeover Pics 3 - Upcoming Events 12 - Momma Does It Best: Mother Duncan’s 4 - Rant ‘N Rave: I Heart Paducah 13 - Mother Duncan’s Cont’d Contents 5 - Movie Going For Morons 14 - Freezor Pop Fest Why Must the Holidays Be Hell-of-Days? 15 - The Season For Giving: Local Charities 6 - Sex In the Sticks and Where To Get Your X-Mas Gifts 7 - Win A Date With Bella 16 - Shana McCoy’s Makeover Check Out Bella Bazooka’s Face- 8 - Old Crow Medicine Show Interview 17 - The Best of Paducah book page, with pics of us being sa- 9 - Old Crow Cont’d 18 - The Best of Paducah Cont’d lacious hussies and everything. And 10 - Around Town Pics 19 - The First Ever Affordable Art Show we now have our very own web- site! www.bazookamagazine.com 11 - Around Town Cont’d 20 - Back Cover Editor’s Note Hey Guys! Welcome to the eighth issue of Bazooka Magazine. Man, this thing is just blowing up! In just the past month I have heard from so many new fans who tell me how stoked they are that there is finally an alternative newspaper in town. -

Ctba Newsletter 1208

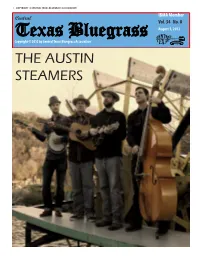

1 COPYRIGHT © CENTRAL TEXAS BLUEGRASS ASSOCIATION IBMA Member Central Vol. 34 No. 8 Texas Bluegrass August 1, 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Central Texas Bluegrass Association THE AUSTIN STEAMERS 2 COPYRIGHT © CENTRAL TEXAS BLUEGRASS ASSOCIATION The Listening Post The Listening Post is a forum established to monitor bluegrass musical recordings, live performances, or events in Texas. Our mailbox sometimes contains CDs for us to review. Here is where you will find reviews of the CD’s Central Texas Bluegrass Association receives as well as reviews of live performances or workshops. CTBA has its Annual Band Scramble - Good fun!! Steep Canyon Rangers Nobody Knows You (2012), Rounder Records. Together for 12 years, the Steep Canyon Rangers are most noted in recent years for backing comedian Steve Martin. The Rangers stated goal for this CD was to “sep- arate themselves from the pack,” which they manage to do with their strong ar- rangements and top-notch production. Definitely con- temporary grass, nothing Rose in the Tall Grass: Elise Bright (fiddle), Russell Holley-Hart (mando), Tony Kamel (guitar), Lenny Nichols (bass), traditional here. Following Greg Lowery (dobro), Lyndal Cannon (banjo) in the Nickel Creek/Union Station vein, this collection of originals is full of rhyth- mic punches; time and me- ter shifts, which are com- monplace among today’s top groups. Their vocal har- monies are stellar. “Easy To Love” (Tr 3) has a nice Celtic 6/8 feel. Other songs have a swing feel (“Between Mid- night and the Dawn” Tr 4), a ballad (“Natural Disaster” Tr 6) and rocking acous- tic country groove (“Long Shot” Tr 12).