Amsterdam Case Study on Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5.2 De Buiksloterdijk

BUIKSLOTERDIJKPARK Een visie voor het projectgebied Klaprozenweg Noordoost door bewoners Bewonersinitiatief De Groene Draak December 2018 BUIKSLOTERDIJKPARK Een visie voor het projectgebied Klaprozenweg Noordoost door bewoners Een uitgave van het gezamenlijke bewonersinitiatief van de bewoners die wonen in de Buiksloterbreek, de woonbootbewoners van Zijkanaal I en de bewoners van de Marjoleinbuurt te Amsterdam Met dank aan stedebouwkundige Mike Wissing www.mikewissing.nl Copyright © 2018 Bewonersinitiatief De Groene Draak Email: [email protected] Web: www.buiksloterdijkpark.nl Facebook: www.facebook.com/buiksloterdijkpark Inhoudsopgave Buiksloterdijkpark ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Samenvatting ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Inleiding .................................................................................................................................................... 11 2. Ambitie bewoners..................................................................................................................................... 15 3. Buiksloterdijkpark in de huidige situatie .................................................................................................... 17 4. Ontwerpprincipes .................................................................................................................................... -

Stedenbouwkundig Plan Centrumeiland Mei 2016

Stedenbouwkundig plan Centrumeiland mei 2016 Investeringsbesluit Centrumeiland Stedenbouwkundig plan mei 2016 Intro Het Stedenbouwkundig Plan Centrumeiland geeft richting aan de verdere ontwikkeling van het Centrumeiland, het eerste eiland van IJburg 2e fase. Zelfbouw als ontwikkelingsstrategie en de Bewegende Stad als richtlijn voor de inrichting van de openbare ruimte creëren hier een vernieuwend stedelijk woonmilieu. Naast deze ambities kiest de gemeente Amsterdam ervoor om het eiland energieneutraal en rainproof te ontwikkelen. Na de vaststelling van het stedenbouwkundig plan worden in 2016 de eerste zelfbouwkavels uitgegeven. Het ontwerp van de openbare ruimte, de uitvoering van waterkeringen en het gebruik van het nieuwe land voor tijdelijke functies zijn al in 2015 begonnen. De komende jaren wordt het eiland stapsgewijs ontwikkeld, met de hoofdambities uit dit plan als leidraad. Daarnaast biedt het plan ruimte voor aanpassingen in de uitwerking. Inhoudsopgave 11. Beheer openbare ruimte 69 1. Inleiding 7 12. Inrichting openbare ruimte 73 2. Opgave en ambities 13 - Stedelijke woonmilieu 13. Techniek 75 - Zelfbouw - Bewegende stad 14. Grondexploitatie 77 - Duurzaamheid - Tijdelijkheid 15. Welstand 81 - Landschap en natuur IJmeer 16. Planning 85 3. Programma 23 - Woonprogramma 17. Besluitvorming en communicatie 87 - Voorzieningen 18. Juridische aspecten en milieu 89 4. Ontwerp 27 - Plankaart 19. Waterparagraaf 91 - Flexibiliteit - Openbare ruimte - Uitwerking 1e fase Bijlagen 93 5. Zelfbouw 41 Profielen 94 Voorbeelduitwerkingen bouwblokken 98 6. Bewegende Stad 45 Poster ´De Amsterdamse Beweeglogica´ 108 7. Rainproof 51 Colofon 113 8. Energie 53 9. Tijdelijke functies 57 10. Verkeer 63 6 1. Inleiding Aanleiding en doel tot slot is er de Startvisie Centrumeiland 2015 en de uitkomsten van de workshops en expertmeetings die hierover dit voorjaar De vraag naar stedelijk wonen groeit, en daarmee ook de stad zijn gehouden. -

B U U Rtn Aam Gem Een Ten Aam Aan Tal B Ew O N Ers to Taal Aan Tal B

buurtnaam gemeentenaam totaal aantalbewoners onvoldoende zeer aantalbewoners onvoldoende ruim aantalbewoners onvoldoende aantalbewoners zwak aantalbewoners voldoende aantalbewoners voldoende ruim aantalbewoners goed aantalbewoners goed zeer aantalbewoners uitstekend aantalbewoners score* zonder aantalbewoners onvoldoende zeer bewoners aandeel onvoldoende ruim bewoners aandeel onvoldoende bewoners aandeel zwak bewoners aandeel voldoende bewoners aandeel voldoende ruim bewoners aandeel goed bewoners aandeel goed zeer bewoners aandeel uitstekend bewoners aandeel score* zonder bewoners aandeel Stommeer Aalsmeer 6250 0 0 350 1000 1400 2750 600 100 0 100 0% 0% 5% 16% 22% 44% 9% 2% 0% 2% Oosteinde Aalsmeer 7650 0 0 50 150 100 2050 3050 2050 200 0 0% 0% 1% 2% 1% 27% 40% 27% 3% 0% Oosterhout Alkmaar 950 0 0 50 500 100 250 0 0 0 0 0% 0% 8% 54% 9% 29% 0% 0% 0% 0% Overdie-Oost Alkmaar 3000 0 1700 1100 200 0 0 0 0 0 0 0% 56% 37% 7% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% Overdie-West Alkmaar 1100 0 0 100 750 250 50 0 0 0 0 0% 0% 8% 65% 21% 5% 0% 0% 0% 0% Ossenkoppelerhoek-Midden- Almelo 900 0 0 250 650 0 0 0 0 0 0 0% 0% 28% 72% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1% Zuid Centrum Almere-Haven Almere 1600 0 250 150 200 150 500 100 50 250 0 0% 15% 10% 13% 9% 31% 6% 2% 15% 0% De Werven Almere 2650 50 100 250 800 450 1000 50 0 0 0 2% 3% 9% 30% 17% 38% 1% 0% 0% 0% De Hoven Almere 2400 0 150 850 700 50 250 250 150 50 0 0% 7% 35% 29% 1% 11% 10% 6% 2% 0% De Wierden Almere 3300 0 0 200 2000 500 450 150 50 0 0 0% 0% 5% 61% 15% 14% 4% 1% 0% 0% Centrum Almere-Stad Almere 4100 0 0 500 1750 850 900 100 0 -

De Maasbode Verschijnt Dagelijks Des Ochtends En Des Avonds, Uitgezonderd Zon- Dagavond En Maandagochtend

72ste JAARGANG. No. 29071. VRIJDAG 2 FEBRUARI 1940 AVONDBLAD - VIER BLADEN De Maasbode verschijnt dagelijks des ochtends en des avonds, uitgezonderd Zon- dagavond en Maandagochtend. WENNEKER^ ■m SCHIEDAM Mm Abonnementsprijs voor geheel Nederland f 4.50 per kwartaal, f 1 50 per maand, f OJS per week. Losse nummers 9 cent Advertentiën 75 cent per regel. Handels- advertentiën 70 cent per regel Ingezonden Mededeelingen dubbel tarief. Liefdadigheids- advertentiën half tarief. Zaterdagavond en Zondagochtend 10 cent per regel verhooging. MAASBODE regels DE Kabouter-advertentiën groot 5 f 2.—. Uitgave van de NV. de Courant De Maasbode, Groote Markt 30. Rotterdam DAGBLAD VOOR NEDERLAND MET OCHTEND- EN AVOND-EDITIE. |ÜdË OUDE Telefoon 26200 11735. PROEVE? | Postbus 723 — — Giro Het dagblad „Proia", merkt naar aanlei- ding van de Balkan-ententeconferentie op, VOORNAAMSTE NIEUWS. dat de politieke atmosfeer vandaag er op 1 wijst, dat alle Donau- en Balkanstaten vriendschappelijk tegenover gestemd van Italië Melding wordt gemaakt van vier belang- Conferentie zijn. Belgrado rijke punten, op begonnen welke de heden conferentie te Belgrado zouden worden De petroleum-kwestie. aangesneden Pag. L LONDEN, 2 Februari (U.P.) De strtfd om Bij het indienen van de Japansche begroo» heden de Roemeensche petroleum zal betrekkelijk ting heeft de minister van financiën een geopend. de redevoering gehouden Paj}. 2. spoedig tot een einde komen, aldus mee- ning van vooraanstaande personen uit de wereld van de olie-industrie, zoowel als van Een nieuw Russisch offensief aan het front Te moeilijker wordt dit probleem, waar de vooraanstaande diplomaten. in Karelië is tot nu toe op den Finschen te- eene staat (Roemenië) onmiddellijk be- Donderdag vernamen wij uit betrouwbare genstand doodgeloopen Pag. -

'Het Zijn Vooral Hollanders Die Het Kopen'

9 KRANT voor AMSTERDAM OOST EN OMSTREKEN 7 ING steekt veel geld in Komt de zaterdagse Henk Spaan in De Jas amateurvoetbalclubs. markt terug naar IJburg? schreef over Nieuw-West, “Zo’n bedrijf dat zich aan je Vergunning aangevraagd maar praat over Oost. “Dit bindt, dat straalt natuurlijk af voor Reuring, rond was op zondagmiddag om drie op de vereniging.” de haven. uur verreweg de saaiste buurt van 23 Nederland.” 23 OKTOBER 2014 | OPLAGE 70.000 EXEMPLAREN | JAARGANG 7 | INFO@ DEBRUGKRANT.NL | NUMMER 60 | WWW.DEBRUGKRANT.NL Quinoa en gojibessen veroveren Turkse supermarkt ‘Het zijn vooral Hollanders die het kopen’ Nu de vroegere Voge- Op gele A4’tjes is te zien wat er laarwijken van Amster- in de aanbieding is. Niet alleen dam-Oost in rap tempo couscous en fruit, maar ook verhippen, verovert gojibessen en chiazaadjes (waar- mode-eten de Turkse van niemand ooit gehoord had, tot de documentaire Rauw werd en Marokkaanse super- gemaakt, over een moeder en markten. zoon die uitsluitend rauw voed- sel aten). Met name de quinoa Door Rosanne Kropman is niet aan te slepen als die in de reclame is, vertelt de man. Auke Kok schreef een aan- tal maanden geleden over de Quinoa is ook te koop bij monocultuur van winkels in de andere Turkse en Marokkaanse Javastraat. Die groenteboeren supermarkten en groenteboe- beconcurreerden elkaar met ren. Bij Helal et Gida in de Pre- dezelfde producten, zo lazen we toriusstraat hebben ze een hele in Vrij Nederland. stelling vol gezonde en lekkere dingen. Hennepzaadjes, quinoa Een aantal maanden na het maar ook gesuikerde aardbeien, verschijnen van dit stuk is de gedroogde ananas, sneeuw- Javastraat de nieuwe hotspot amandelen en ander verant- van Amsterdam-Oost. -

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam) 52° 21' 14" N 4° 55' 11"Archief E Philip Staal (http://toolserver.org/~geohack Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam)/geohack.php?language=nl& params=52_21_14.19_N_4_55_11.49_E_scale:6250_type:landmark_region:NL& pagename=Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam)) Uit Wikipedia, de vrije encyclopedie De Transvaalbuurt is een buurt van het stadsdeel Oost van de Transvaalbuurt gemeente Amsterdam, onderdeel van de stad Amsterdam in de Nederlandse provincie Noord-Holland. De buurt ligt tussen de Wijk van Amsterdam Transvaalkade in het zuiden, de Wibautstraat in het westen, de spoorlijn tussen Amstelstation en Muiderpoortstation in het noorden en de Linnaeusstraat in het oosten. De buurt heeft een oppervlakte van 38 hectare, telt 4500 woningen en heeft bijna 10.000 inwoners.[1] Inhoud Kerngegevens 1 Oorsprong Gemeente Amsterdam 2 Naam Stadsdeel Oost 3 Statistiek Oppervlakte 38 ha 4 Bronnen Inwoners 10.000 5 Noten Oorsprong De Transvaalbuurt is in de jaren '10 en '20 van de 20e eeuw gebouwd als stadsuitbreidingswijk. Architect Berlage ontwierp het stratenplan: kromme en rechte straten afgewisseld met pleinen en plantsoenen. Veel van de arbeiderswoningen werden gebouwd in de stijl van de Amsterdamse School. Dit maakt dat dat deel van de buurt een eigen waarde heeft, met bijzondere hoekjes en mooie afwerkingen. Nadeel van deze bouw is dat een groot deel van de woningen relatief klein is. Aan de basis van de Transvaalbuurt stonden enkele woningbouwverenigingen, die er huizenblokken -

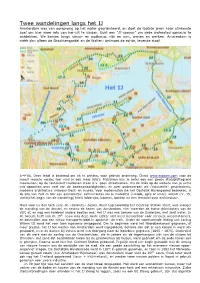

Twee Wandelingen Langs Het IJ

Twee wandelingen langs het IJ Amsterdam was van oorsprong op het water georiënteerd, en doet de laatste jaren haar stinkende best om hier weer iets van her-uit te vinden. Echt een “ IJ-opener” om deze waterstad opnieuw te ontdekken. We komen langs nieuw- en oudbouw, rijk en arm, wonen en werken. Amsterdam is méér dan alleen de Grachtengordel en de Wallen: ontmoet de echte, levende stad! 6-4-’06. Deze tekst is bestemd om uit te printen, voor gebruik onderweg. Check www.ecocam.com voor de meest recente versie; hier vind je ook meer foto’s. Misschien kan je beter ook een goede stadsplattegrond meenemen; op de routekaart hierboven staan b.v. geen straatnamen. Via de links op de website kan je extra info opzoeken over veel van de bezienswaardigheden, en over onderwerpen als (industriële) geschiedenis, moderne architectuur (Havens-Oost) en musea. Voor modernisten die het Oostelijk Havengebied bezoeken, is de site van Talk to Me! een aanradertje: cultuurroutes via je mobieltje (i-mode, gprs of umts). ARCAM (nr. 15, vlakbij het begin van de wandeling) heeft foldertjes, kaarten, boeken en een leestafel over architectuur. Maar voor nu dan toch even de –absolute– basics . Waar tegenwoordig het Centraal Station staat, was vroeger de monding van de Amstel, en tevens de haven van Amsterdam. Hier meerden de trotse driemasters van de VOC af, en nog een heleboel andere bootjes ook. Het IJ was een zeearm van de Zuiderzee, met zout water. In de tweede helft van de 19 de eeuw was deze route echter niet meer bevaarbaar voor serieuze oceaanstomers, en bovendien was een nieuw transportmiddel in opkomst: de trein. -

Did You Know That? Discover the City from the Water And

Canal cruises are one of the most popular attractions in Amsterdam. Did you know that? Discover the city from the water and Beer was what people drank in the choose a route that you think is nice. Middle Ages. Because beer was fi ltered and boiled, it was safer to drink than water, which was usually dirty. People drank about 300 litres per year in those days, nearly a bot- tle a day… even children, although Some of the most beau- they usually drank a lighter type. The tiful bridges are across water of the Amstel river was also the Amstel. Go and see used for brewing beer: a beer brand the 'Magere Brug' was named after it! (Skinny Bridge, which is called that because it’s very narrow) by night, when it’s lit up. HENDRIK BERLAGE In the southern part of Amsterdam lies the Berlage Bridge, named after a well-known architect and urban planner, Hendrik Berlage. The bridge is the entrance to Amsterdam-Zuid, which was built to a You’d expect a river to go on forever, but the river large extent to his specifi cations: Plan Zuid (South Amstel just ends! Long ago, the river fl owed to the IJ Plan). His ‘no frills and no nonsense’ style is easy via the Rokin, the Dam and the Damrak. Nowadays, to recognise: modest but daring. ‘His’ Beurs van most of the water fl ows through the canals. Only Berlage (Berlage Commodity Exchange) in the city a small stream still follows the ancient route beneath centre is one of the top 100 UNESCO monuments the streets through round culverts. -

Toelichting 2012 07 24 GECON

14 augustus 2012 Toelichting Bestemmingsplan Stadion- en Beethovenbuurt 2012 1 14 augustus 2012 Toelichting Bestemmingsplan Stadion- en Beethovenbuurt 2012 Inhoudsopgave Hoofdstuk 1 Inleiding .................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Aanleiding ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Ligging en beschrijving plangebied ................................................................................ 4 1.3 Plangrenzen................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Leeswijzer...................................................................................................................... 5 Hoofdstuk 2 Beschrijving plangebied........................................................................................ 6 2.1 Ontstaansgeschiedenis.................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Stedenbouwkundige structuur........................................................................................ 7 2.3 Functionele structuur ................................................................................................... 10 Hoofdstuk 3 Ontwikkelingsvisie en planbeschrijving ............................................................ 15 3.1 Inleiding ...................................................................................................................... -

National Report the Netherlands

Final National report from The Netherlands Crime Prevention Carousel Nicole Smits Tobias Woldendorp Final National report from The Netherlands Crime Prevention Carousel Amsterdam, 21 december 2006 Nicole Smits Tobias Woldendorp Met medewerking van: Eric Lugtmeijer DSP – groep BV Van Diemenstraat 374 1013 CR Amsterdam T: +31 (0)20 625 75 37 F: +31 (0)20 627 47 59 E: [email protected] W: www.dsp-groep.nl KvK: 33176766 A'dam Inhoudsopgave 1 Introduction - Description of the site 4 1.1 The Bijlmermeer 4 1.2 Description of the research area 7 1.3 Social fysical context of The Bijlmermeer 8 1.4 Method of research in The Netherlands 9 2 Answering the questionnaire 11 Introduction 11 2.1 Aims 11 2.2 Structure and Process 11 2.3 Changes in perception 12 2.4 Security and crime reduction 13 2.5 Design and Crime 16 2.6 Individual Participation 16 2.7 Participation of Police 16 2.8 Participation of residents 17 2.9 Acceptance 17 2.10 Success and Costs 17 2.11 Lessons learned during the renewal 18 2.12 Displacement 19 2.13 Costs 19 2.14 Outlook 19 3 Site visit reports 20 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 What stroke you most in the area? 20 3.3 What lessons can your country learn from the visited project? 21 3.4 What advise would you give to the visited project? 22 3.5 Can you give references (good or bad examples) of projects in your own country? 23 4 Concluding observations 24 Appendix Appendix 1 Site visit reports 26 1.1 Site visit report from Germany 26 1.2 Site visit report from Hungary 32 1.3 Site visit report from Poland 33 1.4 Site visit report from the UK 39 1.5 Site visit report from the Netherlands 41 Appendix 2 Literature 45 Pagina 3 Final National report from The Netherlands DSP - groep 1 Introduction - Description of the site 1.1 The Bijlmermeer Perhaps internationally the most famous neighbourhood of The Netherlands. -

Tour Groot-Amsterdam

Tour Groot-Amsterdam Acht fetsroutes - vierentwintig essays Maurits de Hoog 3 Tour Groot-Amsterdam Acht fetsroutes - vierentwintig essays Maurits de Hoog ormgeving aura mits Gemeente Amsterdam December 2020 www.tourgrootamsterdam.nl mauritsdehoogsall.nl Met dan aan Maru Asmellash Marcel loemendal aroline omb hristiaan van es tte eddes os Gadet ric van der ooi rits almboom ri asveer livier van de anden on chaa eroen chilt aura mits art tuart asiem aa ic ermeulen Aat de ries nhoud Introductie 7 Dit is een doe-boek! 11 Route 1: Voorstad in een moeras - Homeic rommeniedi 2 - andschaseuilleton van het er- 2 - High streets Route 2: Gemengde stad rond de Zaan - angs de aan - aghettiat - Het Hem Route 3: Haven-Stad - Mauettes - en hub in Haven-tad - ordic eague - groen als motor Route 4: Het IJ komt erbij 0 - tedenbouw all-inclusive o meeliten - aterlein 0 2 - rong over het 0 Route 5: Binnenstad - Archiel van onbegreen waliteiten - tadsontwer groot idee - leine truces - Amsterdam 00 Route 6: Amstelstad - ibautas - Het nieuw midden van erualem - ietsring Route 7: Bijlmermeer - edesign ilmermeer 20 - he tri 2 - ntegratie A Route 8: Vecht links 22 - aar ees 20 2 - uiteneiland 20 2 - echt lins 2 Algemeen itbreidingslan tructuurschema Groot-Amsterdam 2 6 ntroductie De beste manier om een stad o regio te leren ennen is o de fets te staen. de website www.tourgrootamsterdam.nl vind e acht fetstochten van ieder twintig ilometer rond een station in de agglomeratie Amsterdam. De fetstochten leiden e langs biondere enomenen in een uitsnede van het verstedelit landscha in en rond de stad een stri ogesannen tussen ort rommeniedi in het noordwesten en ort ittermeer in het uidoosten. -

Proefschrift Wordt Het Begrip Moderniteit Almere, Gebruikt Om De Spanning En Ambivalentie Van Cergy-Pontoise, De Suburbane Stedelijkheid Te Analyseren

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Moderniteit en suburbaniteit in de nieuwe stad: Almere, Cergy-Pontoise, Milton Keynes Nio, I.H.L. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Nio, I. H. L. (2016). Moderniteit en suburbaniteit in de nieuwe stad: Almere, Cergy-Pontoise, Milton Keynes. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 Almere, Cergy-Pontoise, Milton Keynes Keynes Milton Cergy-Pontoise, Almere, Moderniteit De nieuwe steden Almere, Cergy-Pontoise en Milton Moderniteit Keynes zijn het resultaat van pogingen om een vorm en suburbaniteit van stedelijkheid te creëren die de aantrekkelijkheid van het stedelijke en suburbane wonen combineert. in de nieuwe De combinatie van buiten wonen in een eigen huis met een tuin nabij stedelijke voorzieningen zou de stad kracht van de nieuwe steden uitmaken.