Central Costa Rica Deformed Belt: Kinematics of Diffuse Faulting Across the Western Panama Block

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still Living Without the Basics in the 21St Century

rcap_cover_final 6/2/04 2:21 PM Page 1 Still Living Without the Basics in the 21st Century Analyzing the Availability of Wa t e r and Sanitation Services in the United States Rural Community Assistance Partnership Still Living Without the Basics Table of Contents Foreword.............................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary...........................................................................................................................................3 Still Living Without the Basics in the 21st Century ......................................................................................3 Still Living Without the Basics: Analyzing the Availability of Water and Sanitation Services in the United States.......................................................................................................................................................7 Introduction........................................................................................................................................................7 Methodological Layout of the Study...............................................................................................................8 Part I of the Analysis......................................................................................................................................8 Part II of the Analysis....................................................................................................................................9 -

Distritos Declarados Zona Catastrada.Xlsx

Distritos de Zona Catastrada "zona 1" 1-San José 2-Alajuela3-Cartago 4-Heredia 5-Guanacaste 6-Puntarenas 7-Limón 104-PURISCAL 202-SAN RAMON 301-Cartago 304-Jiménez 401-Heredia 405-San Rafael 501-Liberia 508-Tilarán 601-Puntarenas 705- Matina 10409-CHIRES 20212-ZAPOTAL 30101-ORIENTAL 30401-JUAN VIÑAS 40101-HEREDIA 40501-SAN RAFAEL 50104-NACASCOLO 50801-TILARAN 60101-PUNTARENAS 70501-MATINA 10407-DESAMPARADITOS 203-Grecia 30102-OCCIDENTAL 30402-TUCURRIQUE 40102-MERCEDES 40502-SAN JOSECITO 502-Nicoya 50802-QUEBRADA GRANDE 60102-PITAHAYA 703-Siquirres 106-Aserri 20301-GRECIA 30103-CARMEN 30403-PEJIBAYE 40104-ULLOA 40503-SANTIAGO 50202-MANSIÓN 50803-TRONADORA 60103-CHOMES 70302-PACUARITO 10606-MONTERREY 20302-SAN ISIDRO 30104-SAN NICOLÁS 306-Alvarado 402-Barva 40504-ÁNGELES 50203-SAN ANTONIO 50804-SANTA ROSA 60106-MANZANILLO 70307-REVENTAZON 118-Curridabat 20303-SAN JOSE 30105-AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 30601-PACAYAS 40201-BARVA 40505-CONCEPCIÓN 50204-QUEBRADA HONDA 50805-LIBANO 60107-GUACIMAL 704-Talamanca 11803-SANCHEZ 20304-SAN ROQUE 30106-GUADALUPE O ARENILLA 30602-CERVANTES 40202-SAN PEDRO 406-San Isidro 50205-SÁMARA 50806-TIERRAS MORENAS 60108-BARRANCA 70401-BRATSI 11801-CURRIDABAT 20305-TACARES 30107-CORRALILLO 30603-CAPELLADES 40203-SAN PABLO 40601-SAN ISIDRO 50207-BELÉN DE NOSARITA 50807-ARENAL 60109-MONTE VERDE 70404-TELIRE 107-Mora 20307-PUENTE DE PIEDRA 30108-TIERRA BLANCA 305-TURRIALBA 40204-SAN ROQUE 40602-SAN JOSÉ 503-Santa Cruz 509-Nandayure 60112-CHACARITA 10704-PIEDRAS NEGRAS 20308-BOLIVAR 30109-DULCE NOMBRE 30512-CHIRRIPO -

Mapa Del Cantón Santa Ana 09, Distrito 01 a 06

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 1 SAN JOSÉ CANTÓN 09 SANTA ANA 473200 475200 477200 479200 481200 483200 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos Belén Tajo por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 1 San José 1 09 03 U12 Heredia l a Monte Roca 1102400 n 1102400 a C Cantón 09 Santa Ana Almacenes Meco - Plantel Santa Ana Viñedo A Soda Hacienda Herrera B e Cond. Q l é n Cond. Los Sauces Cond. Residencias Los Olivos 1 09 03 U13/U14 Cond. Vista del Roble 1 09 03 U31 Honduras A G ua Ministerio de Hacienda Ebais ch ipe 1 09 03 U32 lín Cond. Corinto Cond. Alcázares Parque Comercial Lindora 1 09 03 U15 Cond. El Pueblo Órgano de Normalización Técnica Ofersa Vindi BlueFlame 1 09 03 U16/U17 e r 1 09 03 U33 b Cond. Altos de Pereira Gasolinera Uno m Hultec o N Puertas del Sol Radial San Antonio in S ombre Cond. Lago Mar Alajuela Planta Tratamiento Lagos de Lindora Sin N Residencial Lago Mar San José Colonia Bella Vista Lindora Park 1 09 03 R26 1 09 03 U27 1 09 03 R04 Servidumbre Eléctrica CTP de Santa Ana Urb. Quirós Centro Educativo Lagos de Lindora 1 09 03 U01/U02 a l Fundación GAD l Hotel Aloft Parque i Q r Iglesia Católica i u e Oracle V Lindora æ b o r í a Forum II d Residencial Valle Verde R Cond. Verdi a BCR P Casas Vita o z 1 09 03 U35 S Cerro Palomas ó 1 09 03 U34 in n Barrio Los Rodríguez N C 1 09 03 U11 om a 1 09 03 U44 b n Banco Lafise ez re al Quebrada Rodrigu ilas 1 09 03 U25 a P Cond. -

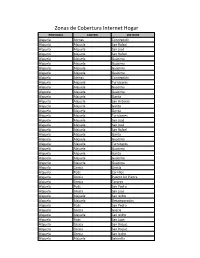

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

ZONA DE CONSERVACIÓN VIAL 1-3 LOS SANTOS Conavi MAPA DE

(! 22 480000 ¤£2 (! UV306 ¤£ (! O R T S I 1 1512 I O R 6 1 IQU LE V IO BRASIL SANTA ANA 2 0 SAN PEDRO H I 10 0 ! C O R V 0 102 1 ( IO C I IR 105 1 R L S 2 R L IL 121 2 8 L 0 A A 0 RIO T A A 167 10104 0 ¬ 0 1 L ¬ « « SAN RAFAEL 1 221 1 FRESES E 177 176 «¬ U 39 0 «¬ 202 7 219 R I ¤£ «¬ «¬ 1 1 ¬ 1 « ¬ C 2 CONCEPCIÓN « 0 39 O 0 I 1 1 £ ¤£ R 22 121 1 ¤ ¤£ 0 215 «¬ 1 «¬ DULCE NOMBRE 1 PASQUÍ 0 CURRIDABAT ESCAZÚ 177 ZAPOTE 8 1 311 «¬ 209 1 UV (! 110 «¬ Q POTRERO CERRADO U BELLO HORIZONTE «¬ 215 E B (! R 176 «¬ A HATILLO D O TIERRA BLANCA A ¬ R O MARIA « I CURRIDABAT 401 A D COLÓN 1 GUI H 1 LA 204 A UV O 0 R ZONA DE CONSERVACIÓN VIAL 1-3 0 214 T N 1 ! ZONA DE CONSERVACIÓ(! N VIAL 1-3 «¬ ( N D «¬ E PIEDRAS NEGRAS A V 136 SAN SEBASTIÁN 11802 E «¬ 211 SAN FRANCISCO R 252 251 218 IO 39 «¬ «¬ «¬ «¬ R I £ IB 210 ¤ TRES RÍOS BANDERILLA 175 R 1 T I ¬ 2 0 « conavi 0 1 conavi SAN FELIPE 19 ¬ 1011 IO « 4 LOS SANTOS 3 LOMAS DE AYARCO PICAGRES LOS SANTOS 211 R (! SAN ANTONIO TIRRASES 213 ¬ 0 110 207 « 3 «¬ ALAJUELITA «¬ «¬ FIERRO BEBEDERO 409 RIO UV PACAC UA (! SAN DIEGO 2 402 R I £ UV O 105 213 ¤ OR «¬ LLANO LEÓN O «¬ 105 SAN ANTONIO «¬ DESAMPARADOS SAN VICENTE ORATORIO R UASI-2019-11-013 / Actualizado a Febrero 2019 IO 210 (! D 219 214 1 A «¬ CALLE FALLAS 03 M «¬ COT PABELLÓN R «¬ 0 A S 4 I O CONCEPCIÓN R A SAN JOSECITO IO G RÍO AZUL U R R E U VILLA NUEVA C S A OCHOMOGO 230 1 0 «¬ 3 409 0 UV 1 PASO ANCHO QUEBRADA GRANDE QUEBRADA HONDA 217 214 PATARRÁ CARTAGO O 239 D «¬ «¬ «¬ A T 209 N E «¬ V RI SAN JUAN DE DIOS E 3 DESAMPARADITOS O J R 0 AR 7 IS IO 0 219 -

Field Guide to Neotectonics of the San Andreas Fault System, Santa Cruz Mountains, in Light of the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake

Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Field Guide to Neotectonics of the San Andreas Fault System, Santa Cruz Mountains, in Light of the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake | Q|s | Landslides (Quaternary) I yv I Vaqueros Sandstone (Oligocene) r-= I San Lorenzo Fm., Rices Mudstone I TSr I member (Eocene-Oligocene) IT- I Butano Sandstone, ' Pnil mudstone member (Eocene) Coseismic surface fractures, ..... dashed where discontinuous, dotted where projected or obscured ___ _ _ Contact, dashed where approximately located >"«»"'"" « « Fault, dotted where concealed V. 43? Strike and dip Strike and dip of of bedding overturned bedding i Vector Scale / (Horizontal Component of Displacement) OPEN-FILE REPORT 90-274 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. Men to Park, California April 27, 1990 Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Field Guide to Neotectonics of the San Andreas Fault System, Santa Cruz Mountains, in Light of the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake David P. Schwartz and Daniel J. Ponti, editors U. S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, CA 94025 with contributions by: Robert S. Anderson U.C. Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA William R. Cotton William Cotton and Associates, Los Gatos, CA Kevin J. Coppersmith Geomatrix Consultants, San Francisco, CA Steven D. Ellen U. S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Edwin L. Harp U. S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Ralph A. -

Codigo Nombre Dirección Regional Circuito Provincia

CODIGO NOMBRE DIRECCIÓN REGIONAL CIRCUITO PROVINCIA CANTON 0646 BAJO BERMUDEZ PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE ACOSTA 0614 JUNQUILLO ARRIBA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0673 MERCEDES NORTE PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0645 ELOY MORUA CARRILLO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0689 JOSE ROJAS ALPIZAR PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0706 RAMON BEDOYA MONGE PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0612 SANTA CECILIA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0615 BELLA VISTA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0648 FLORALIA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0702 ROSARIO SALAZAR MARIN PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0605 SAN FRANCISCO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0611 BAJO BADILLA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0621 JUNQUILLO ABAJO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0622 CAÑALES ARRIBA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL JUAN LUIS GARCIA 0624 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL GONZALEZ 0691 SALAZAR PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL DARIO FLORES 0705 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL HERNANDEZ 3997 LICEO DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 4163 C.T.P. DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL SECCION NOCTURNA 4163 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL C.T.P. DE PURISCAL 4838 NOCTURNO DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL CNV. DARIO FLORES 6247 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL HERNANDEZ LICEO NUEVO DE 6714 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL PURISCAL 0623 CANDELARITA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0679 PEDERNAL PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0684 POLKA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0718 SAN MARTIN PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0608 BAJO LOS MURILLO PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0626 CERBATANA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0631 -

Of Moderate Earthquakes Along the Mexican Seismic Zone Geofísica Internacional, Vol

Geofísica Internacional ISSN: 0016-7169 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Zobin, Vyacheslav M. Distribution of (mb - Ms) of moderate earthquakes along the Mexican seismic zone Geofísica Internacional, vol. 38, núm. 1, january-march, 1999, pp. 43-48 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56838105 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Geofísica Internacional (1999), Vol. 38, Num. 1, pp. 43-48 Distribution of (mb - Ms) of moderate earthquakes along the Mexican seismic zone Vyacheslav M. Zobin Observatorio Vulcanológico, Universidad de Colima, 28045 Colima, Col., México. Received: August 26, 1996; accepted: August 3, 1998. RESUMEN Se estudia la distribución espacial de los valores mb-Ms para 55 sismos en el periodo de 1978 a 1994, con profundidades focales de 0 a 80 km, mb de 4.5 a 5.5, ocurridos a lo largo de la Trinchera Mesoamericana entre 95° y 107°W. Los valores mb-Ms tienen una distribución bimodal, con picos en 0.3 y 0.8 y mínimo en mb-Ms=0.6. Los eventos del primer grupo, con mb-Ms<0.6, se distribuyeron a lo largo de la trinchera en toda la región, comprendida por los bloques Michoacán, Guerrero y Oaxaca; la mayoría de los eventos del segundo grupo, con mb-Ms≥0.6, se encontraron en la parte central de la región en el bloque de Guerrero. -

Central Pacific Coast

st-loc-cos9 Initial Mapping Markgr Date 25-02-10 Road Scale All key roads labelled? Hierarchy Date Title Hydro oast Editor Cxns Spot colours removed? Hierarchy Nthpt Masking in Illustrator done? Symbols ne MC Cxns Date Book Inset/enlargement correct? Off map Notes dest'ns Key Author Cxns Date Final Ed Cxns Date KEY FORMAT SETTINGS Number of Rows (Lines) Editor Check Date MC Check Date Column Widths and Margins MC/CC Signoff Date ©Lonely¨Planet¨Publications¨Pty¨Ltd Central Pacific Coast Why Go? Puntarenas. 353 Stretching from the rough-and-ready port of Puntarenas to Parque.Nacional.. the tiny town of Uvita, the central Pacific coast is home to Carara. 356 both wet and dry tropical rainforests, sun-drenched sandy beaches and a healthy dose of wildlife. On shore, national Playa.Herradura. 359 parks protect endangered squirrel monkeys and scarlet ma- Jacó. 360 caws, while offshore waters are home to migrating whales Playa.Hermosa. 3. 70 and pods of dolphins. Quepos . .373 With so much biodiversity packed into a small geograph- Parque.Nacional.. ic area, it’s no wonder the coastal region is often thought Manuel.Antonio. .387 of as Costa Rica in miniature. Given its close proximity to Dominical. .392 San José and the Central Valley and highlands, and its well- developed system of paved roads, this part of the country is Uvita. .397 a favorite weekend getaway for domestic and international Parque.Nacional.. travelers. Marino.Ballena. .399 While threats of unregulated growth and environmental Ojochal.Area. .400 damage are real, it’s also important to see the bigger picture, namely the stunning nature that first put the central Pacific coast on the map. -

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE

Evangelicals and Political Power in Latin America in Latin America Power and Political Evangelicals JOSÉ LUIS PÉREZ GUADALUPE We are a political foundation that is active One of the most noticeable changes in Latin America in 18 forums for civic education and regional offices throughout Germany. during recent decades has been the rise of the Evangeli- Around 100 offices abroad oversee cal churches from a minority to a powerful factor. This projects in more than 120 countries. Our José Luis Pérez Guadalupe is a professor applies not only to their cultural and social role but increa- headquarters are split between Sankt and researcher at the Universidad del Pacífico Augustin near Bonn and Berlin. singly also to their involvement in politics. While this Postgraduate School, an advisor to the Konrad Adenauer and his principles Peruvian Episcopal Conference (Conferencia development has been evident to observers for quite a define our guidelines, our duty and our Episcopal Peruana) and Vice-President of the while, it especially caught the world´s attention in 2018 mission. The foundation adopted the Institute of Social-Christian Studies of Peru when an Evangelical pastor, Fabricio Alvarado, won the name of the first German Federal Chan- (Instituto de Estudios Social Cristianos - IESC). cellor in 1964 after it emerged from the He has also been in public office as the Minis- first round of the presidential elections in Costa Rica and Society for Christian Democratic Educa- ter of Interior (2015-2016) and President of the — even more so — when Jair Bolsonaro became Presi- tion, which was founded in 1955. National Penitentiary Institute of Peru (Institu- dent of Brazil relying heavily on his close ties to the coun- to Nacional Penitenciario del Perú) We are committed to peace, freedom and (2011-2014). -

AMENAZA VOLCÁNICA EN COSTA RICA 363.34 C733r Costa Rica

Comisión Nacional de Prevención de Riesgos y Atención de Emergencias - Volcán Turrialba - Cartago Costa Rica Turrialba Atención de Emergencias - Volcán Comisión Nacional de Prevención Riesgos y Fotografía: EL RIESGO DERIVADO DE LA AMENAZA VOLCÁNICA EN COSTA RICA EL RIESGO DERIVADO DE LA AMENAZA VOLCÁNICA EN COSTA RICA 363.34 C733r Costa Rica. Comisión Nacional de Prevención de Riesgos y Atención de Emergencias El Riesgo derivado de la amenaza volcánica en Costa Rica / La Comisión; Red Sismológica Nacional; Guillermo E. Alvarado Induni; Alberto Vargas Villalobos; Nuria Campos Sánchez e Ignacio Chaves Salas, coautores – 1a. Ed. – San José, C.R. : CNE, 2014. 32 p. : il. ; 8,5 x 11 cm. ISBN 978-9968-716-31-4 1. Volcán. 2. Erupciones volcánicas. 3. Vigilancia volcánica. 4. Mapa de Riesgo. 5. Gestión del Riesgo. 6. Prevención y mitigación. I. Red Sismológica Nacional. II. Alvarado Induni, Guillermo E. III. Vargas Villalobos, Alberto. IV. Campos Sánchez, Nuria. V. Chaves Salas, Ignacio. VI. Título. Créditos Comisión Nacional de Prevención de Riesgos y Atención de Emergencias. Dirección de Gestión del Riesgo. Unidad de Normalización y Asesoría y Unidad de Investigación y Análisis del Riesgo. Área de Amenazas y Auscultación Sismológica y Volcánica. C.S. Exploración Subterránea / Negocio, Ingeniería, Construcción, ICE Compilación y Elaboración Máster Nuria Campos Sánchez, Unidad de Normalización y Asesoría. Licenciado Ignacio Chaves Salas, Unidad de Investigación y Análisis del Riesgo. Doctor Guillermo E. Alvarado Induni, RSN (UCR-ICE). Máster Alberto Vargas Villalobos, RSN (UCR-ICE). Revisión parcial o total Sergio Mora Yehudi Monestel Rodrigo R. Mora Mauricio Mora Waldo Taylor Geoffroy Avard Luis Madrigal Ramón Araya Foto de portada: Geól. -

The Silent Earthquake of 2002 in the Guerrero Seismic Gap, Mexico

The silent earthquake of 2002 in the Guerrero seismic gap, Mexico (Mw=7.6): inversion of slip on the plate interface and some implications (Submitted to Earth and Planetary Science Letters) A. Iglesiasa, S.K. Singha, A. R. Lowryb, M. Santoyoa, V. Kostoglodova, K. M. Larsonc, S.I. Franco-Sáncheza and T. Mikumoa a Instituto de Geofísica, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F., México b Department of Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA c Department of Aerospace Engineering Science, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA Abstract. We invert GPS position data to map the slip on the plate interface during an aseismic, slow-slip event, which occurred in 2002 in the Guerrero seismic gap of the Mexican subduction zone, lasted for ∼4 months, and was detected by 7 continuous GPS receivers located over an area of ∼550x250 km2. Our best model, under physically reasonable constraints, shows that the slow slip occurred on the transition zone at a distance range of 100 to 170 km from the trench. The average slip was about 22.5 cm 27 (M0∼2.97 x10 dyne-cm, Mw=7.6). This model implies an increased shear stress at the bottom of the locked, seismogenic part of the interface which lies updip from the transition zone, and, hence, an enhanced seismic hazard. The results from other similar subduction zones also favor this model. However, we cannot rule out an alternative model that requires slow slip to invade the seismogenic zone as well. A definitive answer to this critical issue would require more GPS stations and long-term monitoring.