Takla Lake First Nation Climate Change Vulnerability & Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study On

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Enbridge Gateway Pipeline An Assessment of the Impacts of the Proposed Enbridge Gateway Pipeline on the Carrier Sekani First Nations May 2006 Carrier Sekani Tribal Council i Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Proposed Gateway Pipeline ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study was carried out under the direction of, and by many members of the Carrier Sekani First Nations. This work was possible because of the many people who have over the years established the written records of the history, territories, and governance of the Carrier Sekani. Without this foundation, this study would have been difficult if not impossible. This study involved many community members in various capacities including: Community Coordinators/Liaisons Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Bev Ketlo, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Sara Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Rosa McIntosh, Saik’uz First Nation Bev Bird & Ron Winser, Tl’azt’en Nation Michael Teegee & Terry Teegee, Takla Lake First Nation Viola Turner, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Elders, Trapline & Keyoh Holders Interviewed Dick A’huille, Nak’azdli First Nation Moise and Mary Antwoine, Saik’uz First Nation George George, Sr. Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Rita George, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Patrick Isaac, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Peter John, Burns Lake Band Alma Larson, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Betsy and Carl Leon, Nak’azdli First Nation Bernadette McQuarry, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Aileen Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Donald Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Guy Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Vince Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Kenny Sam, Burns Lake Band Lillian Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Ruth Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Joseph Tom, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Translation services provided by Lillian Morris, Wet’suwet’en First Nation. -

Proquest Dissertations

The Distribution of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tar and us caribou) and Moose (Alces alces) in the Fort St. James Region of Northern British Columbia, 1800-1950 Domenico Santomauro B.A., University of Bologna, Italy, 2003 Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Master in Natural Resources and Environmental Studies The University of Northern British Columbia September 2009 © Domenico Santomauro, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothgque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f£rence ISBN: 978-0-494-60853-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-60853-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

British Columbia Geological Survey Geological Fieldwork 1989

GEOLOGY BETWEEN NINA LAKE AND OSILINKA RIVE,R, NORTH-CENTRAL BRITISH COLUMBIA (93N/15, NORTH HALF AND 94C/2, SOUTH HALF) By Filippo Ferri and David M. Melville KEYWORDS: Regionalmapping, Germansen Landing, The northern and eastem sections of the map are bounded, Omineca Belt. Intermontane Superterrane, Slide Mountain respectively, by the Osilinka and 0mine:ca rivers. At lheir Group, Paleozoicstratigraphy, lngenika Group, metamor- confluence the terrainis a relatively subdued and tree covzred phism, lead-zinc-silr,er-baritemineralization area. This is in contrast to the Wolverine Range east oithe OminecaRiverand arugged, unnamedrangeof mountai'ls to the southwest. The southern part of the map area was first mapped at a INTRODUCTION 6-mile scale in the 1940s by Amstrong; (1949).Gahrlelse (1975) examined the northem half in the course of 1:250 000 In 1989 theManson Creek 150 000 mappingproject mapping of the east half of the Fort Grahame map area. encompassed the north half of the Germansen Landing map Monger (1973), and Monger and Patersan (1974) described area (93Ni15) and the south half of the End Lake map area rocks in the map area during a reconnaissance sunfey of (94Ci2). As with previous years, the main aims of this project Paleozoic stratigraphy. To the northwest, Roots (1954) pub- were: to provide a detailed geologicalbase map of the area, to lished a 4-mile map of the Fort Graham west-half sheet. update the mineral inventory database, and to place known Many ofthe correlations made in this paper arewith stratigra- mineral occurrences within a geological framework. phy described by Gabrielse (1963, 1969:1,Nelson and Eirad- ford (1987) and other workers in the Casiar area whera: the The centreof the map area is located some 260kilometres miogeoclinal stratigraphy is quite similar and well known. -

Archaeological Investigations in the Takla Lake Region

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE TAKLA LAKE REGION John McMurdo INTRODUCTION In early spring, 1971, the Pacific Great Eastern Railway was approached by the Archaeology Department of Simon Fraser University, as construction had begun on a new railway linking Fort St. James and Dease Lake. The company was presented with plans for an extensive archaeological survey of the proposed route. It was explained that our purpose was to salvage any archaeological information that might be destroyed in the process of construction. While a grant from the Opportunities for Youth Programme would form part of the budget for this survey, the co-operation of P.G.E. was necessary, particularly in the field of transportation and 10 0 m and board, if the survey was to be successful. By May 15, 1971, P.G.E. had not only granted permission for the survey but had committed itself to providing transportation in the survey area and room and board for a crew of six. By June 15 however, the company had limited the crew size to two, and on the arrival of David Butlin and rcyself in the field on June 17, it was discovered that transportation and other facilities were limited to the area of Takla Lake. Although this area was found to have been extensively disturbed through clearing and bulldozing, a survey was initiated. The results of that survey form the basis of this report. An appendix has also been added which includes the results of discussions with some native residents of Takla Lake. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Takla Lake is approximately 50 miles long and two miles wide at its widest point. -

Paper 08 (Colour).Vp

Toodoggone Geoscience Partnership: Preliminary Bedrock Mapping Results from the Swannell Range: Finlay River – Toodoggone River Area (NTS 94E/2 and 7), North-Central British Columbia1 By L. Diakow, G. Nixon, B. Lane and R. Rhodes KEYWORDS: P3, public-private partnership, Targeted Toodoggone River in the north and east (Fig. 1). The new Geoscience Initiative II (TGI-II), bedrock mapping, result s reporte d below em phasiz e changes in the Early Ju- stratigraphy, Finlay River, Toodoggone River airborne ras sic stra tig ra phy of the Toodoggone from west to east. gamma-ray spectrometric and magnetic survey, Toodoggone River, Finlay River, Toodoggone formation, Black Lake Intrusive Suite, Cu-Au porphyry, epithermal LITHOSTRATIGRAPHIC UNITS Au-Ag Over the past two field seasons, nearly 600 km2 of the INTRODUCTION Swannell Ranges, situ ated be tween the major drainages of the Toodoggone and Finlay rivers and their conflu ence , The Toodoggone Geoscience Part ner ship was ini tiated have been mapped in detai l, thereby refin ing Juras sic stra - in 2003 to gener ate detai led geoscience infor m ati on, in- tig raphy that was, for the most part, pre viously assigne d to clud ing air borne geo phys ics and bed rock ge ol ogy maps, an un di vided Hazelton Group map unit (Diakow et al., that would sup port min ing ex plo ra tion in pre vi ously ex- 1985, 1993). As a conse quence of mapping in 2004, a re - plored and more re mote ter rain in the east-cen tral gion of pre viously un divided Ju rassic rocks is now iden ti - Toodoggone River and McConnell Creek map ar eas, which fied as part of the Toodoggone form ati on. -

GEOLOGY of the EARLY JURASSIC TOODOGGONE FORMATION and GOLD-SILVER DEPOSITS in the TOODOGGONE RIVER MAP AREA, NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA by Larry J

Province of British Columbia MINERAL RESOURCES DIVISION Ministry oi Energy, Mines and Geological Survey Branch Petroleum Resources Hon. Anne Edwards, Minister GEOLOGY OF THE EARLY JURASSIC TOODOGGONE FORMATION AND GOLD-SILVER DEPOSITS IN THE TOODOGGONE RIVER MAP AREA, NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA By Larry J. Diakow, Andrejs Panteleyev, and Tom G. Schroeter BULLETIN 86 MINERAL RESOURCES DIVISION Geological Survey Branch Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Diakow, Larry, I. Geology of the early Jurassic Toodoggone Formation and gold-silvei depositsin the Toodoggone River map area, northern British Columbia VICTORIA BRITISH COLUMBIA (Bulletin, ISSN 0226-7497; 86) CANADA Issued by Geological Survey Branch. Includes bibliographical references: p January 1993 ISBNO-7718-9277-2 1. Geology - Stratigraphic - Jurassic. 2. Gold ores Geological researchfor this -Geology - British Columbia - Toodoggone River Region. 3. Silver ores - British Columbia - Toodoggone River publication was completed during Region. 4. Geology - British Columbia - Toodoggone the period 1981 to 1984. River Region. 5. Toodoggone Formation (B.C.) I. Fanteleyev, Andrejs, 1942- 11. Schroeter, T. G. In. British Columbia. Geological Survey Branch. IV. British Columbia. V. Title. VI. Series: Bulletin (British Columbia. Minisrry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources); 86. TN414C32B731992 551.7'66'0971185 C92-092349.6 Lawyers gold-silver deposit looking northwesterly with Amethyst Gold Breccia (AGB) and Cliff Creek (CC) zones indicated. Cheni Gold Mines camp is in the lower centre and the mill site at the left of the photograph. Flat-lying ash-flow tuffs of the Saunders Member (Unit 6) form the dissected plateauand scarps in the foreground. Silica-clay-alunite capping Alberts Hump, similar to nearby precious metal bearing advanced argillic altered rocks of the A1 deposit (AI), are barely visible to the north of Toodoggone River and 5 kilometres beyond Metsantan Mountain. -

Of the Babine River I I an Historical Perspective

I I Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I a _° IIIII 'ïWiiuWï r". 12020078 I ÎN Al 11 D NON-NATIVE USE OF THE BABINE RIVER I I AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 1 by Brendan O'Donnell 1 Native Affairs Division Issue 2 1 Policy and Program Planning I I I I I 1#1 Fisheries Pêches and Oceans et Océans Canad1a I INTRODUCTION The following is one of a series of reports on the historicai uses of waterways in New Brunswick and British Columbia. These reports are narrative outlines of how Indian and non-native populations have used these .rivers, with emphasis on navigability, tidal influence, riparian interests, settlement patterns, commercial use and fishing rights. These historical reports were requested by the Interdepartmental Reserve Boundary Review Committee, a body comprising representatives from Indian Affairs and Northern Development [DIAND], Justice, Energy, Mines and Resources [EMR], and chaired by Fisheries and Oceans. The committee is tasked with establishing a government position on reserve boundaries that can assist in determining the area of application of Indian Band fishing by-laws. Although each report in this series is as different as the waterway it describes, there is a common structural approach to each paper. Each report describes the establishment of Indian eserves along the river; what Licences of Occupation were issued; what instructions were given to surveyors laying out these reserves; how each surveyor laid out each reserve based on his field notes and survey plan; what, if any, fishing rights were considered for the Indian Bands; and how the Indian and non-native populations have used the waterway over the past centuries for both commercial and recreational use. -

Duncan Lake): a Draft Report

Tse Keh Nay Traditional and Contemporary Use and Occupation at Amazay (Duncan Lake): A Draft Report Amazay Lake Photo by Patrice Halley Draft Submission to the Kemess North Joint Review Panel May, 2007 Report Prepared By: Loraine Littlefield Linda Dorricott Deidre Cullon With Contributions By: Jessica Place Pam Tobin On Behalf of the Tse Keh Nay ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written under the direction of the Tse Keh Nay leaders. The authors would like to thank Grand Chief Gordon Pierre and Chief Johnny Pierre of the Tsay Keh Dene First Nation; Chief John Allen French of the Takla Lake First Nation and Chief Donny Van Somer of the Kwadacha First Nation for their support and guidance throughout this project. The authors are particularly indebted to the advisors for this report who took the time to meet with us on very short notice and who generously shared with us their knowledge of Tse Keh Nay history, land and culture. We hope that this report accurately reflects this knowledge. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Grand Chief Gordon Pierre, Ray Izony, Bill Poole, Trevor Tomah, Jean Isaac, Robert Tomah, Chief John Allen French, Josephine West, Frank Williams, Cecilia Williams, Lillian Johnny, Hilda George and Fred Patrick. We would also like to thank the staff at the Prince George band and treaty offices for assembling and providing us with the documents, reports, maps and other materials that were used in this report. J.P. Laplante, Michelle Lochhead, Karl Sturmanis, Kathaleigh George, and Henry Joseph all provided valuable assistance and support to the project. -

REPORT on the Status of Bc First Nations Languages

report on the status of B.C. First Nations Languages Third Edition, 2018 Nłeʔkepmxcín Sgüüx̣s Danezāgé’ Éy7á7juuthem diitiidʔaatx̣ Gitsenimx̱ St̓át̓imcets Dane-Zaa (ᑕᓀ ᖚ) Hul’q’umi’num’ / Halq’eméylem / hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ Háiɫzaqvḷa Nisg̱a’a Sk̲wx̱wú7mesh sníchim Nsyilxcən Dakelh (ᑕᗸᒡ) Kwak̓wala Dene K’e Anishnaubemowin SENĆOŦEN / Malchosen / Lekwungen / Semiahmoo/ T’Sou-ke Witsuwit'en / Nedut'en X̄enaksialak̓ala / X̄a’islak̓ala Tāłtān X̱aad Kil / X̱aaydaa Kil Tsilhqot'in Oowekyala / ’Uik̓ala She shashishalhem Southern Tutchone Sm̓algya̱x Ktunaxa Secwepemctsín Łingít Nuučaan̓uɫ ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ (Nēhiyawēwin) Nuxalk Tse’khene Authors The First Peoples’ Cultural Council serves: Britt Dunlop, Suzanne Gessner, Tracey Herbert • 203 B.C. First Nations & Aliana Parker • 34 languages and more than 90 dialects • First Nations arts and culture organizations Design: Backyard Creative • Indigenous artists • Indigenous education organizations Copyediting: Lauri Seidlitz Cover Art The First Peoples’ Cultural Council has received funding Janine Lott, Title: Okanagan Summer Bounty from the following sources: A celebration of our history, traditions, lands, lake, mountains, sunny skies and all life forms sustained within. Pictographic designs are nestled over a map of our traditional territory. Janine Lott is a syilx Okanagan Elder residing in her home community of Westbank, B.C. She works mainly with hardshell gourds grown in her garden located in the Okanagan Valley. Janine carves, pyro-engraves, paints, sculpts and shapes gourds into artistic creations. She also does multi-media and acrylic artwork on canvas and Aboriginal Neighbours, Anglican Diocese of British wood including block printing. Her work can be found at Columbia, B.C. Arts Council, Canada Council for the Arts, janinelottstudio.com and on Facebook. Department of Canadian Heritage, First Nations Health Authority, First Peoples’ Cultural Foundation, Margaret A. -

Department of Mines and Resources Geology And

CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES MINES AND GEOLOGY BRANCH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN No. 5 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL DEPOSITS OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA WEST OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS BY J. E. Armstrong OTTAWA EDMOND CLOUTIER PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1946 Price, 25 cents CANADA DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES MINES AND GEOLOGY BRANCH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN No. 5 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL DEPOSITS OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA WEST OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS BY J. E. Armstrong OTTAWA EDMOND CLOUTIER PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1946 Price, 25 cents CONTENTS Page Preface............ .................... .......................... ...... ........................................................ .... .. ........... v Introduction........... h····················································· ···············.- ··············· ·· ········ ··· ··················· 1 Physiography. .............. .. ............ ... ......................... ·... ............. ....................... .......................... .... 3 General geology.. ........ ....................................................................... .... .. ... ...... ....... .. .... .... .. .. .. 6 Precambr ian........................................................................................... .... .. ....................... 6 Palreozoic................ .. .... .. .. ....... ................. ... ... ...... ................ ......... .... ... ... ...... .. .. .. ... .. .... ....... 7 Mesozoic.......................... .......... .................................................... -

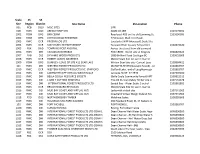

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale. -

Toodoggone/Kemess

Moosehorn Lake 590000 600000 610000 Swannell620000 Ranges 630000 640000 Claw Mountain (! (! Tseehee Creek Harmon Creek Moosehorn Creek (! (! Harmon Peak Metsantan Range Adoogacho Creek Hiamadam Creek Peak Range Pulpit Lake Midas Creek µ 6380000 6380000 (! Junkers Creek Breccia Peak Finlay Ranch Russel Property (! Park (! Midas Lake (! Moyez Creek (! Lower Belle Lake Dedeeya Creek Belle Creek (! Contact Peak Peak Range Katharine Creek (! Abesti Creek (!(! (! Upper Belle Lake (! McClair Creek Tuff Peak (! (! Oxide Creek (! Mulvaney Creek (! BONANZA (! (! (! Oxide Peak Jack Lee Creek Ç(! (! Gordonia Gulch (! The MacGregors (! Alberts Hump (! (! (! Mount Gordonia Moyez Creek (! (! (! THESIS II/III (! (! Ç (! PORPHYRY PEARL Belle Creek ^_(! (! Ç(! BV(! (! (! 6370000 (! (! 6370000 (! (! Antoine Louis Creek (! (! (! (! (! (! (! Mount Hartley Metsantan Creek Alberts Hump Creek METS JD Toodoggone Peak (! (! ^_(! (!^_ Mount Estabrook Bronlund Peak Metsantan Creek Mount Katharine (! ! (! ( Katharine Creek (! Metsantan Lake (! Mulvaney Creek (! (! (! Spatsizi McClair Creek Toodoggone Lake Jack Lee Creek Plateau Moosehorn Creek Wilderness Park DUKE Metsantan Pass Kadah Lake (! Toodoggone River MCCLAIR CREEK PLACER ^_ (! Kadah Creek Ç(! (! (! (! Bend Mountain Mount Graves(! Bronlund Creek Lawyers Creek (! (! Lawyers (! (! GOLDEN STRANGER (! (! Property Saunders Creek (! (! (! 6360000 (! (! 6360000 ^_ (! NEW LAW Edozadelly Mountain ^_(! Jock Creek (! (! (! (! (! AGB (! Ç(! (! (! (! CLIFF CREEK (! (! (! Ç (! (! DUKE'S RIDGE ^_(! GOLDEN NEIGHBOR 1 Ç (!