The Concept of Irreversibility: Its Use in the Sustainable Development and Precautionary Principle Literatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

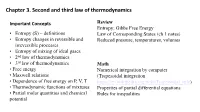

Chapter 3. Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics

Chapter 3. Second and third law of thermodynamics Important Concepts Review Entropy; Gibbs Free Energy • Entropy (S) – definitions Law of Corresponding States (ch 1 notes) • Entropy changes in reversible and Reduced pressure, temperatures, volumes irreversible processes • Entropy of mixing of ideal gases • 2nd law of thermodynamics • 3rd law of thermodynamics Math • Free energy Numerical integration by computer • Maxwell relations (Trapezoidal integration • Dependence of free energy on P, V, T https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezoidal_rule) • Thermodynamic functions of mixtures Properties of partial differential equations • Partial molar quantities and chemical Rules for inequalities potential Major Concept Review • Adiabats vs. isotherms p1V1 p2V2 • Sign convention for work and heat w done on c=C /R vm system, q supplied to system : + p1V1 p2V2 =Cp/CV w done by system, q removed from system : c c V1T1 V2T2 - • Joule-Thomson expansion (DH=0); • State variables depend on final & initial state; not Joule-Thomson coefficient, inversion path. temperature • Reversible change occurs in series of equilibrium V states T TT V P p • Adiabatic q = 0; Isothermal DT = 0 H CP • Equations of state for enthalpy, H and internal • Formation reaction; enthalpies of energy, U reaction, Hess’s Law; other changes D rxn H iD f Hi i T D rxn H Drxn Href DrxnCpdT Tref • Calorimetry Spontaneous and Nonspontaneous Changes First Law: when one form of energy is converted to another, the total energy in universe is conserved. • Does not give any other restriction on a process • But many processes have a natural direction Examples • gas expands into a vacuum; not the reverse • can burn paper; can't unburn paper • heat never flows spontaneously from cold to hot These changes are called nonspontaneous changes. -

Thermodynamic Entropy As an Indicator for Urban Sustainability?

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Engineering 00 (2017) 000–000 www.elsevier.com/locate/procedia Urban Transitions Conference, Shanghai, September 2016 Thermodynamic entropy as an indicator for urban sustainability? Ben Purvisa,*, Yong Maoa, Darren Robinsona aLaboratory of Urban Complexity and Sustainability, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK bSecond affiliation, Address, City and Postcode, Country Abstract As foci of economic activity, resource consumption, and the production of material waste and pollution, cities represent both a major hurdle and yet also a source of great potential for achieving the goal of sustainability. Motivated by the desire to better understand and measure sustainability in quantitative terms we explore the applicability of thermodynamic entropy to urban systems as a tool for evaluating sustainability. Having comprehensively reviewed the application of thermodynamic entropy to urban systems we argue that the role it can hope to play in characterising sustainability is limited. We show that thermodynamic entropy may be considered as a measure of energy efficiency, but must be complimented by other indices to form part of a broader measure of urban sustainability. © 2017 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. Peer-review under responsibility of the organizing committee of the Urban Transitions Conference. Keywords: entropy; sustainability; thermodynamics; city; indicators; exergy; second law 1. Introduction The notion of using thermodynamic concepts as a tool for better understanding the problems relating to “sustainability” is not a new one. Ayres and Kneese (1969) [1] are credited with popularising the use of physical conservation principles in economic thinking. Georgescu-Roegen was the first to consider the relationship between the second law of thermodynamics and the degradation of natural resources [2]. -

The Influence of Thermodynamic Ideas on Ecological Economics: an Interdisciplinary Critique

Sustainability 2009, 1, 1195-1225; doi:10.3390/su1041195 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article The Influence of Thermodynamic Ideas on Ecological Economics: An Interdisciplinary Critique Geoffrey P. Hammond 1,2,* and Adrian B. Winnett 1,3 1 Institute for Sustainable Energy & the Environment (I•SEE), University of Bath, Bath, BA2 7AY, UK 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bath, Bath, BA2 7AY, UK 3 Department of Economics, University of Bath, Bath, BA2 7AY, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-12-2538-6168; Fax: +44-12-2538-6928. Received: 10 October 2009 / Accepted: 24 November 2009 / Published: 1 December 2009 Abstract: The influence of thermodynamics on the emerging transdisciplinary field of ‗ecological economics‘ is critically reviewed from an interdisciplinary perspective. It is viewed through the lens provided by the ‗bioeconomist‘ Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1906–1994) and his advocacy of ‗the Entropy Law‘ as a determinant of economic scarcity. It is argued that exergy is a more easily understood thermodynamic property than is entropy to represent irreversibilities in complex systems, and that the behaviour of energy and matter are not equally mirrored by thermodynamic laws. Thermodynamic insights as typically employed in ecological economics are simply analogues or metaphors of reality. They should therefore be empirically tested against the real world. Keywords: thermodynamic analysis; energy; entropy; exergy; ecological economics; environmental economics; exergoeconomics; complexity; natural capital; sustainability Sustainability 2009, 1 1196 ―A theory is the more impressive, the greater the simplicity of its premises is, the more different kinds of things it relates, and the more extended is its area of applicability. -

Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes. Physical Processes in Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems, Transport Processes

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 195 434 SE 033 595 AUTHOR Levin, Michael: Gallucci, V. F. TITLE Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes. Physical Processes in Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems, Transport Processes. TNSTITUTION Washington Univ., Seattle. Center for Quantitative Science in Forestry, Fisheries and Wildlife. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Oct 79 GRANT NSF-GZ-2980: NSF-SED74-17696 NOTE 87p.: For related documents, see SE 033 581-597. EDFS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Biology: College Science: Computer Assisted Instruction: Computer Programs: Ecology; Energy: Environmental Education: Evolution; Higher Education: Instructional Materials: *Interdisciplinary Approach; *Mathematical Applications: Physical Sciences; Science Education: Science Instruction; *Thermodynamics ABSTRACT These materials were designed to be used by life science students for instruction in the application of physical theory tc ecosystem operation. Most modules contain computer programs which are built around a particular application of a physical process. This module describes the application of irreversible thermodynamics to biology. It begins with explanations of basic concepts such as energy, enthalpy, entropy, and thermodynamic processes and variables. The First Principle of Thermodynamics is reviewed and an extensive treatment of the Second Principle of Thermodynamics is used to demonstrate the basic differences between reversible and irreversible processes. A set of theoretical and philosophical questions is discussed. This last section uses irreversible thermodynamics in exploring a scientific definition of life, as well as for the study of evolution and the origin of life. The reader is assumed to be familiar with elementary classical thermodynamics and differential calculus. Examples and problems throughout the module illustrate applications to the biosciences. -

Equilibrium and Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics: Concept of Entropy Part-2

Equilibrium and Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics: Concept of Entropy Part-2 v Entropy Production v Onsager’s reciprocal relations Dr. Rakesh Kumar Pandey Associate Professor, Department of Chemistry MGCU, Bihar Numerical: Calculate the standard entropy change for the following process at 298 K: H2O(g)⟶H2O(l) o The value of the standard entropy change at room temperature, ΔS 298, is the difference between the standard entropy of the product, H2O(l), and the standard entropy of the reactant, H2O(g). o o o ΔS 298 = S 298(H2O (l))−S 298(H2O(g)) (70.0 Jmol−1K−1)−(188.8Jmol−1K−1) =−118.8 Jmol−1K−1 Use the data of Standard Molar Entropy Values of Selected Substances at 25°C to calculate ΔS° for each reaction. 1) H2(g)+1/2O2 (g)→H2O(l) 2) CH3OH(l) + HCl(g) → CH3Cl(g) + H2O(l) 3) H2(g) + Br2(l) → 2HBr(g) 4) Zn(s) + 2HCl(aq) → ZnCl2(s) + H2(g) For standard molar entropy values see the following webpage: https://www.chem.wisc.edu/deptfiles/genchem/netorial/modules/thermodynamics/table.htm Note: Students should also try more numerical questions Entropy Production: In a reversible process, net change in the entropy of the system and surroundings is zero therefore, it is only possible to produce entropy in an irreversible process. Entropy production (or generation) is the amount of entropy which is produced in any irreversible processes. This can be achieved via heat and mass transfer processes including motion of bodies, heat exchange, fluid flow, substances expanding or mixing, deformation of solids, and any irreversible thermodynamic cycle, including thermal machines such as power plants, heat engines, refrigerators, heat pumps, and air conditioners. -

The Carnot Cycle, Reversibility and Entropy

entropy Article The Carnot Cycle, Reversibility and Entropy David Sands Department of Physics and Mathematics, University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, UK; [email protected] Abstract: The Carnot cycle and the attendant notions of reversibility and entropy are examined. It is shown how the modern view of these concepts still corresponds to the ideas Clausius laid down in the nineteenth century. As such, they reflect the outmoded idea, current at the time, that heat is motion. It is shown how this view of heat led Clausius to develop the entropy of a body based on the work that could be performed in a reversible process rather than the work that is actually performed in an irreversible process. In consequence, Clausius built into entropy a conflict with energy conservation, which is concerned with actual changes in energy. In this paper, reversibility and irreversibility are investigated by means of a macroscopic formulation of internal mechanisms of damping based on rate equations for the distribution of energy within a gas. It is shown that work processes involving a step change in external pressure, however small, are intrinsically irreversible. However, under idealised conditions of zero damping the gas inside a piston expands and traces out a trajectory through the space of equilibrium states. Therefore, the entropy change due to heat flow from the reservoir matches the entropy change of the equilibrium states. This trajectory can be traced out in reverse as the piston reverses direction, but if the external conditions are adjusted appropriately, the gas can be made to trace out a Carnot cycle in P-V space. -

Lecture 11 Second Law of Thermodynamics

LECTURE 11 SECOND LAW OF THERMODYNAMICS Lecture instructor: Kazumi Tolich Lecture 11 2 ¨ Reading chapter 18.5 to 18.10 ¤ The second law of thermodynamics ¤ Heat engines ¤ Refrigerators ¤ Air conditions ¤ Heat pumps ¤ Entropy Second law of thermodynamics 3 ¨ The second law of thermodynamics states: Thermal energy flows spontaneously from higher to lower temperature. Heat engines are always less than 100% efficient at using thermal energy to do work. The total entropy of all the participants in any physical process cannot decrease during that process. Heat engines 4 ¨ Heat engines depend on the spontaneous heat flow from hot to cold to do work. ¨ In each cycle, the hot reservoir supplies heat �" to the engine which does work �and exhausts heat �$ to the cold reservoir. � = �" − �$ ¨ The energy efficiency of a heat engine is given by � � = �" Carnot’s theorem and maximum efficiency 5 ¨ The maximum-efficiency heat engine is described in Carnot’s theorem: If an engine operating between two constant-temperature reservoirs is to have maximum efficiency, it must be an engine in which all processes are reversible. In addition, all reversible engines operating between the same two temperatures, �$ and �", have the same efficiency. ¨ This is an idealization; no real engine can be perfectly reversible. ¨ The maximum efficiency of a heat engine (Carnot engine) can be written as: �$ �*+, = 1 − �" Quiz: 1 6 ¨ Consider the heat engine at right. �. denotes the heat extracted from the hot reservoir, and �/ denotes the heat exhausted to the cold reservoir in one cycle. What is the work done by this engine in one cycle in Joules? Quiz: 11-1 answer 7 ¨ 4000 J ¨ � = �. -

Lecture 2: Reversibility and Work September 20, 2018 1 / 18 Some More Definitions?

...Thermodynamics Equilibrium implies the existence of a thermodynamic quantity Mechanical equilibrium implies Pressure Thermal Equilibrium implies Temperature Zeroth LAW of thermodynamics: There exists a single quantity which determines thermal equilibrium Named by RH Fowler, great great grandsupervisor to Prof Ackland Graeme Ackland Lecture 2: Reversibility and Work September 20, 2018 1 / 18 Some more definitions? Process: when the state variables change in time. Reversible Process: when every step for the system and its surroundings can be reversed. A reversible process involves a series of equilibrium states. Irreversible Process - when the direction of the arrow of time is important. IRREVERSIBILITY DEFINES THE CONCEPT OF TIME. Graeme Ackland Lecture 2: Reversibility and Work September 20, 2018 2 / 18 Reversible processes Reversible processes are quasistatic - system is in equilibrium and the trajectory can be drawn on a PV indicator diagram. Irreversible processes procede via non-equilibrium states, with gradients of T and P, where the system would continue to change if the external driving force is removed (e.g. stirring) It is possible to get between two states of a system by reversible OR irreversible process. The final state of the system is the same regardless of reversibility, but the surroundings are different. Graeme Ackland Lecture 2: Reversibility and Work September 20, 2018 3 / 18 How to tell if a process is reversible Consider a process between equilibrium endpoints (starting point and finishing point) eg compression of gas by a piston from state (P1,V1) to (P2, V2). For a reversible process, every (infinitesimal) step { for both the system and its surroundings { can be reversed. -

Heat Engines ∆=+E QW Thermo Processes Int • Adiabatic – No Heat Exchanged

Chapter 19 Heat Engines ∆=+E QW Thermo Processes int • Adiabatic – No heat exchanged – Q = 0 and ∆Eint = W • Isobaric – Constant pressure – W = P (Vf – Vi) and ∆Eint = Q + W • Isochoric – Constant Volume – W = 0 and ∆Eint = Q • Isothermal – Constant temperature V W= nRT ln i ∆Eint = 0 and Q = -W Vf C and C P V Note that for all ideal gases: where R = 8.31 J/mol K is the universal gas constant. Slide 17-80 Heat Engines Refrigerators Important Concepts 2nd Law: Perfect Heat Engine Can NOT exist! No energy is expelled to the cold reservoir It takes in some amount of energy and does an equal amount of work e = 100% It is an impossible engine No Free Lunch! Limit of efficiency is a Carnot Engine Reversible and Irreversible Processes The reversible process is an idealization. All real processes on Earth are irreversible. Example of an approximate reversible process: The gas is compressed isothermally The gas is in contact with an energy reservoir Continually transfer just enough energy to keep the temperature constant The change in entropy is equal to zero for a reversible process and increases for irreversible processes. Section 22.3 The Maximum Efficiency Qc TTcc =andec = 1 − QThh Th Qc Tc Qh Th COPC = = COPH = = W TThc− W TThc− Heat Engines . In a steam turbine of a modern power plant, expanding steam does work by spinning the turbine. The steam is then condensed to liquid water and pumped back to the boiler to start the process again. First heat is transferred to the water in the boiler to create steam, and later heat is transferred out of the water to an external cold reservoir, in the condenser. -

Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes Deals with Systems Which Are Not at Equilibrium but Are Nevertheless Stationary

Materials Science & Metallurgy Part III Course M16 Materials Modelling H. K. D. H. Bhadeshia Lecture 11: Irreversible Processes Thermodynamics generally deals with measurable properties of materials, formulated on the basis of equilibrium. Thus, properties such as entropy and free energy are, on an appropriate scale, static and time–invariant during equilibrium. There are other parameters not relevant to the discussion of equilibrium: thermal conductivity, diffusivity and viscosity, but which are interesting because they can describe a second kind of time–independence, that of the steady– state (Denbigh, 1955). Thus, the concentration profile does not change during steady–state diffusion, even though energy is being dissipated by the diffusion. The thermodynamics of irreversible processes deals with systems which are not at equilibrium but are nevertheless stationary. The theory in effect uses thermodynamics to deal with kinetic phenomena. There is nevertheless, a distinction between the thermodynamics of irreversible processes and kinetics (Denbigh). The former applies strictly to the steady–state, whereas there is no such restriction on kinetic theory. Reversibility A process whose direction can be changed by an infinitesimal alteration in the external con- ditions is called reversible. Consider the example illustrated in Fig. 1, which deals with the response of an ideal gas contained at uniform pressure within a cylinder, any change being achieved by the motion of the piston. For any starting point on the P/V curve, if the applica- tion of an infinitesimal force causes the piston to move slowly to an adjacent position still on the curve, then the process is reversible since energy has not been dissipated. -

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics

Chapter 19 Chemical Thermodynamics Kinetics How fast a rxn. proceeds Equilibrium How far a rxn proceeds towards completion Thermodynamics Study of energy relationships & changes which occur during chemical & physical processes 1 A) First Law of Thermodynamics Law of Conservation of Energy : Energy can be neither created nor destroyed but may be converted from one form to another. Energy lost = Energy gained by system by surroundings 1) Internal Energy, E E = total energy of the system Actual value of E cannot be determined Only ΔE 2 2) Relating ΔE to Heat & Work 2 types of energy exchanges occur between system & surroundings Heat & Work + q : heat absorbed, endothermic ! q : heat evolved, exothermic + w : work done on the system ! w : work done by the system a) First Law ΔE = q + w 3 3) System and Surroundings System = portion we single out for study - focus attention on changes which occur w/in definite boundaries Surroundings = everything else System : Contents of rx. flask Surround. : Flask & everything outside it Agueous soln. rx : System : dissolved ions & molecules Surround : H2O that forms the soln. 4 B) Thermodynamic State & State Functions Thermodynamic State of a System defined by completely specifying ALL properites of the system - P, V, T, composition, physical st. 1) State Function prop. of a system determined by specifying its state. depends only on its present conditions & NOT how it got there ΔE = Efinal ! Einitial independent of path taken to carry out the change - Also is an extensive prop. 5 C) Enthalpy In ordinary chem. rx., work generally arises as a result of pressure-volume changes Inc. -

Heat Engines Important Concepts Heat Engines Refrigerators Important Concepts 2Nd Law of Thermo

Chapter 19 Heat Engines Important Concepts Heat Engines Refrigerators Important Concepts 2nd Law of Thermo • Heat flows spontaneously from a substance at a higher temperature to a substance at a lower temperature and does not flow spontaneously in the reverse direction. • Heat flows from hot to cold. • Alternative: Irreversible processes must have an increase in Entropy; Reversible processes have no change in Entropy. • Entropy is a measure of disorder in a system 2nd Law: Perfect Heat Engine Can NOT exist! No energy is expelled to the cold reservoir It takes in some amount of energy and does an equal amount of work e = 100% It is an impossible engine No Free Lunch! Limit of efficiency is a Carnot Engine Second Law – Clausius Form It is impossible to construct a cyclical machine whose sole effect is to transfer energy continuously by heat from one object to another object at a higher temperature without the input of energy by work. Or – energy does not transfer spontaneously by heat from a cold object to a hot object. Section 22.2 Heat Pumps and Refrigerators Heat engines can run in reverse This is not a natural direction of energy transfer Must put some energy into a device to do this Devices that do this are called heat pumps or refrigerators energy transferred at high temp Q COP = h heating work done by heat pump W energy transferred at low temp Q COP = C cooling work done by heat pump W A heat pump, is essentially an air conditioner installed backward. It extracts energy from colder air outside and deposits it in a warmer room.