A Clash of Worldviews: the Impact of Modern Western Notion of Progress on Indigenous Naga Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the Meeting of REDD+ Working Group for North Eastern States of India

Minutes of the Meeting of REDD+ Working Group for North Eastern States of India (06 September 2018) Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education (An Autonomous Body of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India) P.O. New Forest, Dehradun – 248006 (INDIA) © Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education, 2018 Published by: Biodiversity and Climate Change Division Directorate of Research Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education Dehradun 2016 Editors: Dr. Dhruba J. Das, Scientist ‘E’, RFRI, Jorhat Dr. R.S. Rawat, Scientist In-charge, Biodiversity and Climate Change Division, ICFRE, Dehradun CONTENTS 1 Background 1 2 Minutes of the Meeting 2 2.1 Inaugural Session 2 2.2 Technical Session 1 3 2.3 Technical Session 2 6 2.4 Concluding Session 6 Annex - I: Agenda of the meeting 8 Annex - II: List of participants 9 Annex - III: Presentation on Introduction to REDD+ and its implementation framework at National and International 10 level Annex - IV: Presentation on REDD+ Working Group for 15 North-Eastern States and future roads map Annex - V: Presentation on Prospects of REDD+ projects in 17 North East India Annex - VI: Presentation on REDD+ Pilot Project in Mizoram 19 & Preparation of SRAP for the State Annex - VII: Presentation on Experience of Mawphlang 25 Khasi Hills Community REDD+ project Annex - VIII: Presentation on Activities connected with 35 REDD+ Manipur Minutes of the Meeting of REDD+ Working Group for North Eastern States of India 1. Background Indian council of Forestry research and Education (ICFRE) in collaboration with International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) is implementing ‘REDD+ Himalayas Project’. -

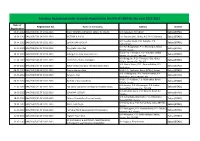

Ngos Registered in the State of Assam 2012-13.Pdf

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2012-2013 Date of Registration No. Name of the Society Address District Registration 09-04-2012 BAK/260/E/01 OF 2012-2013 JEUTY GRAMYA UNNAYAN SAMITTEE (JGUS) Vill. Batiamari, PO Kalbari Baksa (BTAD) 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/02 OF 2012-2013 VICTORY-X N.G.O. H.O. Barama (Niz-Juluki), P.O. & P.S. Barama Baksa (BTAD) Vill. Katajhar Gaon, P.O. Katajhar, P.S. 10-04-2012 BAK/260/E/03 OF 2012-2013 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Baksa (BTAD) Gobardhana Vill.-Pub Bangnabari, P.O.-Mushalpur, Baksa 11-04-2012 BAK/260/E/04 OF 2012-2013 Daugaphu Aiju Afad Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. Vill. & P.O.-Tamulpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Baksa 24-04-2012 BAK/260/E/05 OF 2012-2013 Udangshree Jana Sewa Samittee Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367 Vill.-Baregaon, P.O.- Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 27-04-2012 BAK/260/E/06 OF 2012-2013 RamDhenu N.g.o., Baregaon Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Natun Sripur, P.O.- Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/07 OF 2012-2013 Natun Sripur (Sonapur /Khristan Basti) Baro Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/08 OF 2012-2013 Dodere Harimu Afat Vill.& P.O.-Laukhata, Baksa (BTAD), Assam. Baksa (BTAD) Vill.-Goldingpara, P.O.-Pamua Pathar, P.S.- 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/09 OF 2012-2013 Jwngma Afat Baksa (BTAD) Mushalpur, Baksa (BTAD), Ass. Vill.& P.O.-Adalbari, P.S.-Mushalpur, Baksa 04-05-2012 BAK/260/E/10 OF 2012-2013 Barhukha Sport Academy Baksa (BTAD) (BTAD), Assam. -

2001 Asia Harvest Newsletters

Asia Harvest Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe! (Joel 3:13) Box 17 - Chang Klan P.O. - Chiang Mai 50101 - THAILAND Tel: (66-53) 801-487 Fax: (66-53) 800-665 Email: [email protected] Web: www.antioch.com.sg/mission/asianmo April 2001 - Newsletter #61 China’s Neglected Minorities Asia Harvest 2 May 2001 FrFromom thethe FrFrontont LinesLines with Paul and Joy In the last issue of our newsletter we introduced you to our new name, Asia Harvest. This issue we introduce you to our new style of newsletter. We believe a large part of our ministry is to profile and present unreached people groups to Christians around the world. Thanks to the Lord, we have seen and heard of thousands of Christians praying for these needy groups, and efforts have been made by many ministries to take the Gospel to those who have never heard it before. Often we handed to our printer excellent and visually powerful color pictures of minority people, only to be disappointed when the completed newsletter came back in black and white, losing the impact it had in color. A few months ago we asked our printer, just out of curiosity, how much more it would cost if our newsletter was all in full color. We were shocked to find the differences were minimal! In fact, it costs just a few cents more to print in color than in black and white! For this reason we plan to produce our newsletters in color. Hopefully the visual difference will help generate even more prayer and interest in the unreached peoples of Asia! Please look through the pictures in this issue and see the differ- ence color makes. -

THE WARRIOR 1 Vol. 48. No.06 SEPTEMBER 2019

THE VOL-48 NO.06 SEPTEMBER 2019 THE WARRIOR 1 A DIPR MONTHLY MAGAZINEA DIPR MONTHLY MAGAZINE WARRIOR Vol. 48. No.06 SEPTEMBER 2019 Governor, R. N. Ravi, Chief Minister, Neiphiu Rio, their lady wives and Deputy Chief Minister, Y. Patton during the civic reception honouring the new Governor of Nagaland, R.N. Ravi at NBCC Convention Centre, Kohima on 16th August 2019. [email protected] ipr.nagaland.gov.in www.facebook.com/dipr.nagaland NagaNewsApp Chief Justice (Acting), Gauhati High Court, Arup Kumar Goswami administering the Oath of Office to R.N. Ravi as the 19th Governor of Nagaland at Durbar Hall, Raj Bhavan, Kohima on 1st August 2019. Governor of Nagaland, R.N. Ravi called on the Prime Governor of Nagaland, R.N. Ravi called on the President of India, Ram Nath Minister of India, Narendra Modi at 7, Lok Kalyan Marg, Kovind at New Delhi on 6th August 2019. New Delhi on 8th August 2019. CONTENTS THE WARRIOR A DIPR MONTHLY MAGAZINE REGULARS Editor : DZÜVINUO THEÜNUO Sub Editor : MHONLUMI PATTON Published by: Official Orders & Notifications 4 Government of Nagaland DIRECTORATE OF INFORMATION & PUBLIC RELATIONS State Round Up 9 IPR Citadel, New Capital Complex, Kohima - 797001, Nagaland Districts Round Up 49 © 2019, Government of Nagaland Development Activities 67 Directorate of Information & Public Relations email: [email protected] For advertisement: [email protected] Views and opinions expressed in the contributed articles are not those of the Editor nor do these necessarily reflect the policies or views of the Government of Nagaland. Scan the code to install Naga News Designed & Printed by app from Google Playstore artworks Nagaland-Kohima 4 THE WARRIOR VOL-48 NO.06 SEPTEMBER 2019 A DIPR MONTHLY MAGAZINE OFFICIAL ORDERS and NOTIFICATIONS FINANCE DEPARTMENT INFORMS General Provident Fund (GPF) Rule 11 provides that the Government shall pay the due interest as per prescribed rate pertaining to each year to the subscriber’s account. -

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

Committee on the Welfare of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (2010-2011)

SCTC No. 737 COMMITTEE ON THE WELFARE OF SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES (2010-2011) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) TWELFTH REPORT ON MINISTRY OF TRIBAL AFFAIRS Examination of Programmes for the Development of Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PTGs) Presented to Speaker, Lok Sabha on 30.04.2011 Presented to Lok Sabha on 06.09.2011 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 06.09.2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI April, 2011/, Vaisakha, 1933 (Saka) Price : ` 165.00 CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ................................................................. (iii) INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ (v) Chapter I A Introductory ............................................................................ 1 B Objective ................................................................................. 5 C Activities undertaken by States for development of PTGs ..... 5 Chapter II—Implementation of Schemes for Development of PTGs A Programmes/Schemes for PTGs .............................................. 16 B Funding Pattern and CCD Plans.............................................. 20 C Amount Released to State Governments and NGOs ............... 21 D Details of Beneficiaries ............................................................ 26 Chapter III—Monitoring of Scheme A Administrative Structure ......................................................... 36 B Monitoring System ................................................................. 38 C Evaluation Study of PTG -

Tribes in India 208 Reading

Department of Social Work Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Regional Campus Manipur Name of The Paper: Tribal Development (218) Semester: IV Course Faculty: Ajeet Kumar Pankaj Disclaimer There is no claim of the originality of the material and it given only for students to study. This is mare compilation from various books, articles, and magazine for the students. A Substantial portion of reading is from compiled reading of Algappa University and IGNOU. UNIT I Tribes: Definition Concept of Tribes Tribes of India: Definition Characteristics of the tribal community Historical Background of Tribes- Socio- economic Condition of Tribes in Pre and Post Colonial Period Culture and Language of Major Tribes PVTGs Geographical Distribution of Tribes MoTA Constitutional Safeguards UNIT II Understanding Tribal Culture in India-Melas, Festivals, and Yatras Ghotul Samakka Sarakka Festival North East Tribal Festival Food habits, Religion, and Lifestyle Tribal Culture and Economy UNIT III Contemporary Issues of Tribes-Health, Education, Livelihood, Migration, Displacement, Divorce, Domestic Violence and Dowry UNIT IV Tribal Movement and Tribal Leaders, Land Reform Movement, The Santhal Insurrection, The Munda Rebellion, The Bodo Movement, Jharkhand Movement, Introduction and Origine of other Major Tribal Movement of India and its Impact, Tribal Human Rights UNIT V Policies and Programmes: Government Interventions for Tribal Development Role of Tribes in Economic Growth Importance of Education Role of Social Work Definition Of Tribe A series of definition have been offered by the earlier Anthropologists like Morgan, Tylor, Perry, Rivers, and Lowie to cover a social group known as tribe. These definitions are, by no means complete and these professional Anthropologists have not been able to develop a set of precise indices to classify groups as ―tribalǁ or ―non tribalǁ. -

In Tupelo, Scene Wants ® Check to Keep up Sites to Tell You About Local Time at Djournal.Com

see. hear. do. August 14-20 • 2008 North Mississippi’s entertainment guide Staind rolls into Tupelo for Saturday show ‘PINEAPPLE EXPRESS’ , SALTILLO’S JUSTIN POSEY , CONCERT GUIDE 2E scene August 14-20, 2008 what’s TOP 10 Blog songs High® Five Sited NBC took the gold last week, while rival broad- ®WMSV 91.1, 5.“I Kissed a Girl,” Katy cast networks barely placed. Propelled by just Make Scene World Class Radio Perry the first three nights of the Summer Olympics, Adult album 6.“American Boy,” Estelle NBC scored an average of 17.67 million viewers, Shine with Kanye West Now your alternative while its nearest competitor, CBS, averaged just 1.“Come Around,” Counting 7.“Viva la Vida,” Coldplay 5.68 million, according to Nielsen Media Crows 8.“Forever,” Chris Brown Research figures released Tuesday. blog choice 2.“Peace, Love & Happi- 9.“When I Grow Up,”The BY SHEENA BARNETT ness,” G. Love & Special Pussycat Dolls Scene Sauce 10.“A Little Bit Longer,” There are millions of 3.“Staying With Me,” Los Jonas Brothers music and entertainment Lonely Boys Web sites out there. ® www.billboard.com ®VIDEO RENTALS 4.“Hope,” Jack Johnson 1.“21,” Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. There are some for coun- Hot country songs 5.“Viva la Vida,” Coldplay 2.“The Bank Job,” Lionsgate Home Entertainment. try music. 1.“All I Want to Do,” Sugar- Some for 6.“Old Enough,” Raconteurs land ® 3.“College Road Trip,” Buena Vista Home Entertain- TELEVISION indie rock. 7.“I'm Amazed,” My 2.“You Look Good in My 1.“Summer Olympics Opening Ceremony,” NBC. -

The Yimchunger Nagas: Local Histories and Changing Identity in Nagaland, Northeast India*

The Yimchunger Nagas: Local Histories and Changing Identity in Nagaland, Northeast India* Debojyoti Das Introduction Ethnic identity, as Stanley J. Tambiah writes, is above all a collective identity (Tambiah 1989: 335). For example, in northeastern India, we are self-proclaimed Nagas, Khasis, Garos, Mizos, Manipuris and so on. Ethnic identity is a self-conscious and articulated identity that substantialises and naturalises one or more attributes, the conventional ones being skin colour, language, and religion. These attributes are attached to collectivities as being innate to them and as having mythic historical legacy. The central components in this description of identity are ideas of inheritance, ancestry and descent, place or territory of origin, and the sharing of kinship. Any one or combination of these components may be invoked as a claim according to context and calculation of advantages. Such ethnic collectivities are believed to be bounded, self-producing and enduring through time. Although the actors themselves, whilst invoking these claims, speak as if ethnic boundaries are clear-cut and defined for all time, and think of ethnic collectivities as self-reproducing bounded groups, it is also clear that from a dynamic and processual perspective there are many precedents for changes in identity, for the incorporation and assimilation of new members, and for changing the scale and criteria of a collective identity. Ethnic labels are porous in function. The phenomenon of * I wish to acknowledge the Felix Scholarship for supporting my ethnographic and archival research in Nagaland, India. I will like to thank Omeo Kumar Das Institution of Social Change and Development, SOAS Anthropology and Sociology Department- Christopher Von Furer- Haimendorf Fieldwork Grant, Royal Anthropological Institute- Emislie Horniman Anthropology Fund and The University of London- Central Research Fund for supporting my PhD fieldwork during (2008-10). -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Unit-26 History and Geographical Spread

UNIT-26 HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD . Structure 26.0 Objectives 26.1 Introduction 26.2 Cultural Pattern . 26.3 Geographical Spread:Tribal Zones 263.1, Northern and North-Eastern 2633' Central _ 2633 . South-Western 263.4 . Scattered 26.4 History, Language and Ethnicity 26.4.1 Northern and North-eakern Tribes 26.42 Central Indian Tribes 26.43 South-Western Tribes 26.4.4 Scattered Tribes 265 Let Us Sum Up 26.6 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A DaMa Tribal Girl, Gqjarat. Appendix ( 26.0 OBJECTIVES ; i, This Unit attempts to analyse history and geographical spread of tribes. After reading this unit you uould know about : / cultural spread of tribes, and , the tribal culture with respect to its history and geographical spread in the Northern, NorthiEastem, Central, South-Westem, and scattered zones, and 1 languhges and ethnicity of a few tribes. { 26.1 INTRODUCTION -+ The tribal groups are presumed to form the oldest ethnological sector of the national population. Tribal population of India is spread all over the country. However, in Haryana, Punjab,Chandigarh, DeUli,Goa and Pondicherry there exist very little tribal population.The rest of the states and union territories possess fairly good number of tribal population. You wiU find that forest and hilly areas possess greater concentration of tribal population; while in the plains their number isquite less. Madhya Pradesh registers the largest number oftribes (73) followed by Anrnachal Pradesh (62), Orissa (56), Maharashtra (52), Andhra Pradesh (43), etc. The vast variety and numbers of Indian tribes and tribal groups have\always been a matter of great social and literary discourse for the past several decades. -

Rengma Nagas Demand Autonomous Council

Rengma Nagas demand autonomous council They write to Union Home Minister and Assam Chief Minister, asking for their voices to be heard Vijaita Singh have no history in the Reng- the Rengma Nagas, whose New Delhi ma Hills. People who are population is around The Rengma Nagas in Assam presently living in Rengma 22,000. We are also de- have written to Union Home Hills are from Assam, Aruna- manding a separate legisla- Minister Amit Shah demand- chal Pradesh and Meghalaya. tive seat for Rengmas,” he ing an autonomous district They speak different dialects said. council amid a decision by and do not know Karbi lan- The National Socialist the Central and the State go- guage of Karbi Anglong,” the Council of Nagaland or NSCN vernments to upgrade the memorandum said. (Isak-Muivah), which is in Karbi Anglong Autonomous RNPC president K. Solo- talks with the Centre for a Council (KAAC) into a terri- mon Rengma told The Hindu peace deal, said in a state- torial council. that the government was on ment on Monday that the The Rengma Naga Peo- the verge of taking a decision Rengma issue was one of the ples’ Council (RNPC), a regis- Long fight:The Rengma Naga community has been seeking without taking them on important agendas of the tered body, said in the mem- board and thus they had “Indo-Naga political talks” an automous council for many years now. * FILE PHOTO orandum that the Rengmas written to Mr. Shah and and no authority should go were the first tribal people in Narrating its history, the sam and Nagaland at the Chief Minister Himanta Bis- far enough to override their Assam to have encountered council said that during the time of creation of Nagaland wa Sarma.