Eight Is Enough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2019

JANUARY 2019 Monday-Friday Daytime Schedule 1 TUESDAY 7:30 Colorado Experience "The Redstone Castle" Built by the “Fuel King of the West,” All programming subject to change 7:00 We'll Meet Again "Escape from Cuba" Join John C. Osgood, this “Ruby of the Rockies” a. m. morning p. m. afternoon/evening Ann Curry as two men search for the people represents the exquisite styles and social who helped them come to the U.S. when a culture of 20th century American elite. This = Rocky Mountain PBS original program they fled Castro's Cuba. (Date) = shown on this date only castle stands as a monument to the empire 8:00 Great Performances "From Vienna: The New built by one of Colorado’s most successful 4:30 Painting and Travel with Roger & Year's Celebration 2019" Ring in the New entrepreneurs and represents a change in Sarah Bansemer Year with the Vienna Philharmonic under the social policy concerning labor management 5:00 Priscilla's Yoga Stretches baton of conductor Christian Thielemann at relations. Explore the extravagant halls of 5:30 Classical Stretch: By Essentrics the Musikverein. Hosted by Hugh Bonneville the Redstone Castle and learn of its struggle and featuring favorite Strauss Family waltzes 6:00 Peg + Cat for survival through multiple owners and accompanied by the dancing of the Vienna flirtation with destruction. a 6:30 Arthur City Ballet. 7:00 Ready Jet Go! 8:00 Pioneers of Television "Primetime Soaps" 9:30 Memory Rescue with Daniel Amen, MD "Dallas" and "Dynasty" kicked off the 7:30 Wild Kratts Dr. -

SPRING 2006 3 in the L NEWS

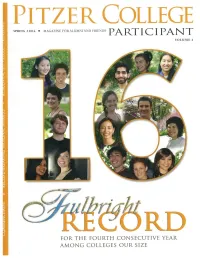

PITZER COLLEGE SPRIN G 2 0 0 6 • MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS pART I c I pANT VOLUME 4 FOR THE FOURTH CONSECUTIVE YEAR AMONG COLLEGES OUR SIZE PITZER COLLEGE FIRST TH INGS MAGA7.1Nl l <>• •'""'" "" rRILNI)\ PA R.T I C I PANT FIRST President Lauro Skondero Trombley Jenniphr Goodman '84 Wins Editor Susan Andrews Managing Editor Third Annual Alumni Award Joy Collier Designer Emily Covolconti he Third Annual Distinguished Alumni Sports Editor Award was presented Catherine Okereke '00 T during Alumni Weekend on Contributing Writers April29 at the All Class Susan Andrews Reunion Dinner. The award, Carol Brandt the highest honor bestowed Richard Chute '84 upon a graduate of Pitzer Joy Collier College, recognizes an alum Pamela David '74 na/us who has brought Tonyo Eveleth honor and distinction to the Alice Jung '0 1 College through her or his Peter Nardi outstanding achievements. Catherine Okereke '00 This year, the College hon Norma Rodriguez ored the creative energy of Shell (Zoe) Someth '83 an alumna and her many Sherri Stiles '87 achievements in film produc linus Yamane tion. Jenniphr Goodman, a 1984 graduate of Pitzer, Contributing Photographers embodies the College's com Emily Covolconti mitment to producing Phil Channing engaged, socially responsi Joy Collier ble, citizens of the world. Robert Hernandez '06 After four amazing years Alice Maple '09 at Pitzer, Jenniphr received Donald A. McFarlane her B.A. in creative writing Catherine Okereke '00 and film making in 1984. She Distinguished Alumni Award recipient Jenniphr Goodman '84 wilh Kirk Reynolds returned to her hometown in Professor of English and the History of Ideas Barry Sanders Cover Des ign Cleveland, Ohio, to teach art Emily Covolconti to preschool children after Award in 1993 at Pitzer College, to graduating. -

Balloon Boy” Hoax, a Call to Regulate the Long-Ignored Issue of Parental Exploitation of Children

WHAT WILL IT TAKE?: IN THE WAKE OF THE OUTRAGEOUS “BALLOON BOY” HOAX, A CALL TO REGULATE THE LONG-IGNORED ISSUE OF PARENTAL EXPLOITATION OF CHILDREN RAMON RAMIREZ* I. INTRODUCTION On October 15, 2009, the world was captivated by the story of a little boy in peril as he allegedly floated through the Colorado sky in a homemade balloon.1 The boy’s parents, Richard and Mayumi Heene, first alerted authorities with an “emotional and desperate” 9-1-1 call, claiming that their son Falcon was in a balloon that had taken off from their backyard.2 Rescuers set out on a “frantic” ninety-minute chase that ended when the balloon “made a soft landing some 90 miles away;” but to their surprise, no one was in it.3 One of Falcon’s older brothers repeatedly said he saw Falcon get into the balloon before it took off, and a sheriff’s deputy said he saw something fall from the balloon while it was in the air, causing rescuers to fear the worst: Falcon fell out.4 The story appeared to have a happy ending after Falcon emerged from the family attic where he was hiding because his father yelled at him earlier in the day.5 That evening, the family appeared on Larry King Live on the Cable News Network (“CNN”) to tell their story, and when asked by his parents why he did not come out of the attic when they initially called for him, Falcon responded, “[y]ou guys said we did this for the show”; with that, suspicions began to arise.6 * J.D., University of Southern California Law School, 2011. -

Programs & Exhibitions

PROGRAMS & EXHIBITIONS Winter/Spring 2020 To purchase tickets by phone call (212) 485-9268 letter | exhibitions | calendar | programs | family | membership | general information Dear Friends, Until recently, American democracy wasn’t up for debate—it was simply fundamental to our way of life. But things have changed, don’t you agree? According to a recent survey, less than a third of Americans born after 1980 consider it essential to live in a democracy. Here at New-York Historical, our outlook is nonpartisan Buck Ennis, Crain’s New York Business and our audiences represent the entire political spectrum. But there is one thing we all agree on: living in a democracy is essential indeed. The exhibitions and public programs you find in the following pages bear witness to this view, speaking to the importance of our democratic principles and the American institutions that carry them out. A spectacular new exhibition on the history of women’s suffrage in our Joyce B. Cowin Women’s History Gallery this spring sheds new light on the movements that led to the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution 100 years ago; a major exhibition on Bill Graham, a refugee from Nazi Germany who brought us the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, and many other staples of rock & roll, stresses our proud democratic tradition of welcoming immigrants and refugees; and, as part of a unique New-York Historical–Asia Society collaboration during Asia Society’s inaugural Triennial, an exhibition of extraordinary works from both institutions will be accompanied by a new site-specific performance by drummer/composer Susie Ibarra in our Patricia D. -

Program Guide

JANUARY 2019 VOL. 49 NO. 1 PROGRAM GUIDE New Season 8 premiering Saturday, January 5, at 9:00 p.m. NEW YEAR'S NEW SERIES "VICTORIA" RETURNS SPECIALS "SHAKESPEARE & HATHAWAY" FOR SEASON 3 Page 2 Page 7 Page 7 MONDAY – FRIDAY 6:00 Peg + Cat 6:30 Arthur 7:00 Ready Jet Go! 7:30 Wild Kratts 8:00 Nature Cat 8:30 Curious George 9:00 Let's Go Luna! NEW YEAR’S EVE 9:30 Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood 9:00 p.m. 10:00 Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood 10:30 Pinkalicious & Peterrific LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER 11:00 Sesame Street New York Philharmonic New Year’s Eve 11:30 Splash and Bubbles with Renee Fleming Ring in the New Year with the New York Philharmonic and opera 12:00 Dinosaur Train great Renee Fleming. 12:30 The Cat in the Hat Knows a Lot About That! 10:30 p.m. 1:00 Sesame Street 1:30 Super WHY! Austin City Limits Hall of Fame Celebrate the induction of new Austin City Limits Hall of Famers 2:00 Pinkalicious & Peterrific Ray Charles, Los Lobos and Marcia Ball, with performances by 2:30 Let's Go Luna! Boz Scaggs, Gary Clark Jr., Norah Jones and more. 3:00 Nature Cat 3:30 Wild Kratts 4:00 Wild Kratts NEW YEAR’S DAY 4:30 Odd Squad Noon–5:30 p.m. 5:00 Odd Squad Get help starting your New Year’s resolution with an afternoon of 5:30 Weather World self-help programming. (Re-airs at 5:45 p.m.) 6:00 BBC World News America 9:00 p.m. -

WSKG-HDTV Dec 2018

1 next for the #MeToo movement. of Representatives, discusses the 5 Wednesday American conservative movement. 8pm Reindeer Family & Me 8 Saturday 9pm Martin Clunes: Islands of 8pm Midsomer Murders Australia Midsomer Life, Part 1 10pm Martin Clunes: Islands of The detectives investigate when WSKG-HDTV Australia the ex-wife's lover of the owner of 11pm Martin Clunes: Islands of Midsomer Life magazine dies. Dec 2018 Australia 9pm Father Brown expanded listings 12am Amanpour and Company The Crackpot of the Empire 10pm Are You Being Served? 6 Thursday The Club 1 Saturday 8pm Expressions (WSKG) Songs of the Season 10:30pm Are You Being Served? 8pm Members' Choice 9pm 800 Words Do You Take This Man? 12am Members' Choice The first anniversary of his wife's 11pm Still Open All Hours 2 Sunday death looms large for George as Christmas 2016 8pm Members' Choice war breaks out with the in-laws. As Christmas approaches, grocer 12am Members' Choice 10pm Doc Martin Granville's cost-saving measures at 3 Monday Rescue Me his shop are as cunning as ever. Life in Portwenn transpires to get in 11:30pm Austin City Limits 8pm Antiques Roadshow Band of Horses/Parker Millsap Albuquerque, Hour Two Martin's way as he questions if Louisa will come back to him. Enjoy modern roots rock with Band Great finds include a 1969 Jasper of Horses. Parker Millsap supports Johns flag print and a 1939 11pm Doc Martin The Shock of the New The Very Last Day. inscribed "Pinocchio" book. 12:30am Front and Center 9pm Expressions (WSKG) Martin may have me this match after Martin's first session with Dr. -

Mothers on Mothers: Maternal Readings of Popular Television

From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. The volume examines the ways in which these women find pleasure, empowerment, escapist fantasy, displeasure and frustration in popular depictions of motherhood. The research seeks to present the MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION voice of the maternal audience and, as such, it takes as its starting REBECCA FEASEY point those maternal depictions and motherwork representations that are highlighted by this demographic, including figures such as Tess Daly and Katie Hopkins and programmes like TeenMom and Kirstie Allsopp’s oeuvre. Rebecca Feasey is Senior Lecturer in Film and Media Communications at Bath Spa University. She has published a range of work on the representation of gender in popular media culture, including book-length studies on masculinity and popular television and motherhood on the small screen. REBECCA FEASEY ISBN 978-0343-1826-6 www.peterlang.com PETER LANG From Supernanny to Gilmore Girls, from Katie Price to Holly Willoughby, a MOTHERS ON wide range of examples of mothers and motherhood appear on television today. Drawing on questionnaires completed by mothers across the UK, this MOTHERS ON MOTHERS book sheds new light on the varied and diverse ways in which expectant, new MATERNAL READINGS OF POPULAR TELEVISION and existing mothers make sense of popular representations of motherhood on television. -

January 2019 New Season

JANUARY 2019 Program Guide NEW SEASON SUN JAN 13 @ 8PM 316-838-3090 •kpts.org [email protected] • 316-838-3090 Special New Year's Day programs 8AM & 3:30PM to help you begin the year inspired. Memory Rescue with Daniel Amen, M.D. 10AM Aging Backwards 2: Connective Tissue Revealed with Miranda Esmonde-White Noon New Year Healthy Brain - Happy Life with Dr. Suzuki 2PM New Outlook 3 Steps to Incredible Health with Tuesday, January 1 @ 8AM - 5PM Joel Fuhrman, M.D. Tuesday, January 1 @ 8PM Ring in the New Year with the Vienna Philharmonic under the baton of conductor Christian Thielemann at the Musikverein. Hosted by Hugh Bonneville and featuring favorite Strauss Family waltzes accompanied by the dancing of the Vienna City Ballet. Wednesday, January 2 @ 8PM The New Horizons spacecraft attempts to fly by a mysterious object Pluto and Beyond known as Ultima Thule, believed to be a primordial building block of the solar system. Three years after taking the first spectacular photos of Pluto, New Horizons is four billion miles from Earth, trying to achieve the most distant flyby in NASA’s history. If successful, it will shed light on one of the least understood regions of our solar system: the Kuiper Belt. NOVA is embedded with the New Horizons mission team, following the action in real time as they uncover the secrets of what lies beyond Pluto. Saturday, January 5 @ 9PM Season 8 Saturdays @ 8PM Beginning January 5 January 5 Mysterious Ways After successfully rekindling their relationship, Louisa and Martin are living together again, but Louisa finds herself juggling too many responsibilities at once. -

Looking At, Through, and with Youtube Paul A

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Communication College of Arts & Sciences 2014 Looking at, through, and with YouTube Paul A. Soukup Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/comm Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Soukup, Paul A. (2014). Looking at, through, and with YouTube. Communication Research Trends, 33(3), 3-34. CRT allows the authors to retain copyright. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking at, with, and through YouTube™ Paul A. Soukup, S.J. [email protected] 1. Looking at YouTube Begun in 2004, YouTube rapidly grew as a digi- history and a simple explanation of how the platform tal video site achieving 98.8 million viewers in the works.) YouTube was not the first attempt to manage United States watching 5.3 billion videos by early 2009 online video. One of the first, shareyourworld.com (Jarboe, 2009, p. xxii). Within a year of its founding, begin 1997, but failed, probably due to immature tech- Google purchased the platform. Succeeding far beyond nology (Woog, 2009, pp. 9–10). In 2000 Singingfish what and where other video sharing sites had attempt- appeared as a public site acquired by Thompson ed, YouTube soon held a dominant position as a Web Multimedia. Further acquired by AOL in 2003, it even- 2.0 anchor (Jarboe, 2009, pp. -

January 2019

January 2019 Channel 8.1 with antenna 1008 on Cox & CenturyLink Prism, 8 on Suddenlink BBC WORLD NEWS AMERICA M-F 4:30 p.m. PLATE & POUR CRONKITE NEWS M-F 5 p.m. & 11 p.m. Thursdays at 7 p.m., premiering Jan. 10 ARIZONA HORIZON M-F 5:30 p.m. & 10 p.m. PBS NEWSHOUR M-F 6 p.m. NIGHTLY BUSINESS REPORT M-F 10:30 p.m. 7:00 P.M. 7:30 P.M. 8:00 P.M. 8:30 P.M. 9:00 P.M. 9:30 P.M. Symphony for Nature: 1 TUE We'll Meet Again* Escape from Cuba Great Performances* From Vienna: The New Year's Celebration 2019 Britt Orchestra at Crater Lake* 2 WED Nature Fox Tales Nova* Beyond Pluto James Watson: American Masters* 3 THU Check, Please! Arizona Arizona Collectibles Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries Death & Hysteria The Coroner The Foxby Affair 4 FRI Washington Week Arizona Stories Finding Your Roots Map of Stars The Directors* Alfred Hitchcock 5 SAT Celtic Woman: Ancient Land (at 6 p.m.) Great Performances Michael Buble: Tour Stop 148 Desert Dreams 6 SUN Victoria Season 2 on Masterpiece The King Over the Water/The Luxury of Conscience/Comfort and Joy 7 MON Antiques Roadshow* Meadow Brook Hall, Hour 1 Antiques Roadshow Chicago, Hour 1 A Tale of Two Sisters Amelia Earhart 8 TUE Finding Your Roots* Grandparents and Other Strangers We'll Meet Again* The Fight for Women's Rights USS Indianapolis: The Final Chapter* 9 WED Nature* Attenborough and the Sea Dragon Nova* Einstein's Quantum Riddle The Dictator's Playbook* Kim Il Sung 10 THU Plate & Pour* Arizona Collectibles Miss Fisher's Murder Mysteries Death at the Grand The Coroner Pieces of Eight 11 FRI Washington -

“Octomom” As a Case Study in the Ethics of Fertility Treatments

l Rese ca arc ni h li & C f B Journal of o i o l Manninen, J Clinic Res Bioeth 2011, S:1 e a t h n r i c u DOI: 10.4172/2155-9627.S1-002 s o J Clinical Research Bioethics ISSN: 2155-9627 Review Article Open Access Parental, Medical, and Sociological Responsibilities: “Octomom” as a Case Study in the Ethics of Fertility Treatments Bertha Alvarez Manninen* Arizona State University at the West Campus, New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, Phoenix, P.O. Box 37100; Mail Code 2151, Phoenix, AZ 85069, USA Abstract The advent and development of various forms of fertility treatments has made the dream of parenthood concrete for many who cannot achieve it through traditional modes of conception. Yet, like many scientific advances, fertility treatments have been misused. Although still rare compared to the birth of singletons, the number of triplets, quadruplets, and other higher-order multiple births have quadrupled in the past thirty years in the United States, mostly due to the increasingly prevalent use of fertility treatments. In contrast, the number of multiple births has decreased in Europe in recent years, even though 54% of all assistant reproductive technology cycles take place in Europe, most likely because official guidelines have been implemented throughout several countries geared towards reducing the occurrence of higher-order multiple births.1 The gestation of multiple fetuses can result in dire consequences for them. They can be miscarried, stillborn, or die shortly after birth. When they do survive, they are often born prematurely and with a low birth weight, and may suffer from a lifetime of physical or developmental impairments. -

2013 Winter Visions

In this Issue... Early Childhood Party School Board Members VISIONS Recognized VISIONS Volunteering WINTER 2013 ACTS OF KINDNESS Superintendent’S CORNER Wayne Petroelje What an Act of Kindness Can Do A couple my wife and I know chose to share their home with a man who was homeless with a lot of debt. Living with them allowed him time to pay off these debts and again find a place to live for himself. I know they felt privileged to be able to do this for him and this gesture brought the family much joy. Likewise, our daughter and son-in-law committed to a year of feeding several homeless individuals. So, along with their two young boys, they packed lunches at least every two weeks each month and distributed the lunches to these homeless individuals. This was a way of giving back for all they have (even though they have a tight budget themselves). So much of life needs to be about others, not just ourselves. We feel COMING FROM THE HEART a high and are energized by these acts and want to continue to provide acts of kindness. In light of the tragic events at Sandy Hook Elementary, NBC News Correspondent, Ann Curry, Continued on page 3 1 Board of Education Nancy Hawkins President Blaine Lentz Vice President Rick Fedewa Secretary Patti Jandernoa Treasurer FOCUS Thomas White Trustee Wayne Petroelje Superintendent, Ex-Officio Administration Early Childhood Party - Wayne Petroelje Superintendent Dr. Robert Fall Director of Special Education Lee Kleinjans Business Manager Labor of Love Christine M. Callahan Innovative Projects Director Dr.