Caretakers of the Land and Its People (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GVHA-Indigenous-Business-Directory

1 Company Name Business Type Contact Details Website Alexander Traffic Traffic Control Dore Lafortune Alexander Traffic Control is a local company providing traffic N/A Control Ltd. Company control services. Aligned Design Commercial & Lana Pagaduan Aligned Design works in flooring installations and commer- www.aligneddesignfp.co Residential Painting and cial & residential painting. They are 100% Indigenous m (under construction) Flooring Installations owned and operated. AlliedOne Consulting IT Strategy Gina Pala AlliedOne Consulting is a management consulting service www.alliedoneconsulting. specializing in IT Strategy and leadership, as well as Cyber com Security. Animikii Web Design Company Jeff Ward Animikii is a web-services company building custom soft- www.animikii.com (Animikii ware, web-applications and websites. They work with lead- Gwewinzenhs) ing Indigenous groups across North America to leverage technology for social, economic and cultural initiatives. As a 100% Indigenous-owned technology company, Animikii works with their clients to implement solutions that amplify these efforts and achieve better outcomes for Indigenous people in these areas. Atrue Cleaning Commercial & Trudee Paul Atrue Cleaning is a local Indigenous owned cleaning compa- https:// Residential Cleaner ny specializing in commercial & residential cleaning, includ- www.facebook.com/ ing Airbnb rentals. trudeescleaning/ Brandigenous Corporate Branding Jarid Taylor Brandigenous is a custom branded merchandise supplier, www.facebook.com/ crafting authentic marketing merch with an emphasis of brandigenous/ quality over quantity. 2 Company Name Business Type Contact Details Website Brianna Marie Dick Artist- Songhees Nation Brianna Dick Brianna Dick is from the Songhees/Lekwungen Nation in N/A Tealiye Victoria through her father's side with roots to the Namgis Kwakwaka'wakw people in Alert Bay through her mother's side. -

Recognizing and Including Indigenous Cultural Heritage in B.C

POLICY PAPER Recognizing and Including Indigenous Cultural Heritage in B.C. Prepared by Karen Aird, Gretchen Fox and Angie Bain on behalf of First Peoples’ Cultural Council SEPTEMBER 2019 VISION MISSION Our vision is one where B.C. First Nations languages, Our mission is to provide leadership for the arts, culture, and heritage are thriving, accessible and revitalization of First Nations languages, arts, available to the First Nations of British Columbia, and culture, and heritage in British Columbia. the cultural knowledge expressed through Indigenous languages, cultures and arts is recognized and embraced by all citizens of B.C. Acknowledgments We are grateful to the following people for their support throughout the preparation of this paper and for their thoughtful comments, which have improved the paper immensely. Tracey Herbert, CEO, FPCC Suzanne Gessner, Linguist, FPCC Julie Harris, Historian Lisa Prosper, National Sites and Monument Board Leslie LeBourdais, Archaeologist, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Natasha Beedie, Policy Analyst, Assembly of First Nations (Ottawa) Photos in this paper were used with permission from the following photographers: Cover images, left to right: Art Napoleon, Don Bain, Alycia Aird, Amanda Laliberte and Ryan Dickie Back cover images: Lisa Hackett; Pictograph courtesy of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Inside images: Alycia Aird (A.A), Karen Aird (K.A.), Don Bain (D.B.), Tiinesha Begaye (T.B.), Diane Calliou (D.C.), Ryan Dickie (R.D.), Rob Jensen (R.J.), Amanda Laliberte (A.L.), Art Napoleon (A.N.), Garry Oker (G.O.), Susan Snyder (S.S) for more information: First Peoples' Cultural Council T (250) 652-5952 Language Programs F (250) 652-5953 1A Boat Ramp Road E [email protected] Brentwood Bay, B.C. -

First Peoples of the Waterway

GORGE WATERWAY INITIATIVE infosheet WORKING TOGETHER TO BALANCE CONSERVATION , RECREATION AND COMMUNITY VALUES [email protected] • www.gorgewaterway.ca F IRST PEOPLES O F THE WATERWAY Aboriginal people have lived on the land around the Gorge Waterway and Portage Inlet for more than 4,000 years. The Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations are both Coast Salish peoples and are two remaining local bands whose connection to the waterway remains very strong. Jody Watson The rocks representing Camossung and her grandfather are still visible below the Gorge Bridge. F ROM THEN UNTIL NOW treaty rights. The Songhees are accepted, and that is why these are For centuries, the Esquimalt and involved in the BC Treaty plentiful on the Gorge Waterway. Songhees people have used the Commission process with a Because she was greedy, Haylas told waterway for gathering food such broader group of neighbouring her she would look after the food as salmon, herring, oysters and bands, called the Te’Mexw Treaty resources for her people and he turned other shellfish, waterfowl, and Association. The Esquimalt people her and her grandfather into stone. eelgrass. They sometimes took are pursuing other legal and The stones of Camossung and her refuge from northern invading negotiated arrangements. grandfather could be seen for bands in Portage Inlet. During L EGEND O F CAMOSSUNG thousands of years at reversing these times, First Nations’ Haylas the Transformer, Raven and Gorge Falls under what is now settlements were all along the Mink found a young girl, named called Gorge Bridge. There was a waterway stretching into Victoria Camossung, and her grandfather. -

Ethnoecological Investigations of Blue Camas (Camassia Leichtlinii (Baker) Wats., C

"The Queen Root of This Clime": Ethnoecological Investigations of Blue Camas (Camassia leichtlinii (Baker) Wats., C. quamash (Pursh) Greene; Liliaceae) and its Landscapes on Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia Brenda Raye Beckwith B.A., Sacramento State University, Sacramento, 1989 M.Sc., Sacramento State University, Sacramento, 1995 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Biology We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard O Brenda Raye Beckwith, 2004 University of Victoria All right reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. Co-Supervisors: Drs. Nancy J. Turner and Patrick von Aderkas ABSTRACT Bulbs of camas (Camassia leichtlinii and C. quamash; Liliacaeae) were an important native root vegetable in the economies of Straits Salish peoples. Intensive management not only maintained the ecological productivity of &us valued resource but shaped the oak-camas parklands of southern Vancouver Island. Based on these concepts, I tested two hypotheses: Straits Salish management activities maintained sustainable yields of camas bulbs, and their interactions with this root resource created an extensive cultural landscape. I integrated contextual information on the social and environmental histories of the pre- and post-European contact landscape, qualitative records that reviewed Indigenous camas use and management, and quantitative data focused on applied ecological experiments. I described how the cultural landscape of southern Vancouver Island changed over time, especially since European colonization of southern Vancouver Island. Prior to European contact, extended families of local Straits Salish peoples had a complex system of root food production; inherited camas harvesting grounds were maintained within this region. -

1. Canada's Big Chill

JESSICA BALL & ONOWA MCIVOR 1. CANADA’S BIG CHILL Indigenous Languages in Education ABSTRACT wihtaskamihk kîkâc kahkiyaw nîhîyaw pîkiskwîwina î namatîpayiwa wiya môniyâw onîkânîwak kayâs kâkiy sihcikîcik ka nakinahkwâw nîhiyaw osihcikîwina. atawiya anohc kanâta askiy kâpimipayihtâcik î tipahamok nîhiyaw awâsisak kakisinâmâkosicik mîna apisis î tipahamok mîna ta kakwiy miciminamâ nîhiyawîwin. namoya mâka mitoni tapwîy kontayiwâk î nîsohkamâkawinaw ka miciminamâ nipîkiskwîwinân. pako kwayas ka sihcikiy kîspin tâpwiy kâ kakwiy miciminamâ nîhîyawîwin îkwa tapwiy kwayas ka kiskinâhamowâyâ kicowâsim’sinân. ôma masinayikanis îwihcikâtîw tânihki kîkâc kâ namatîpayicik nipîkiskwîwinân îkwa takahki sihcikîwina mîna misowiy kâ apicihtâcik ka pasikwînahkwâw nîhiyawîwin nanântawisi. (Translated into Nîhîyawîwin (Northern Cree) [crk], a language of Canada, by Art Napoleon) Canada’s Indigenous languages are at risk of extinction because of government policies that have actively opposed or neglected them. A few positive steps by government include investments in Aboriginal Head Start, a culturally based early childhood program, as well as a federal Aboriginal Languages Initiative. Overall, however, government and public schools have yet to demonstrate serious support for Indigenous language revitalization. Language-in-education policies must address the historically and legislatively created needs of Indigenous Peoples to increase the number of Indigenous language speakers and honor the right of Indigenous children to be educated in their language and according to their heritage, with culturally meaningful curricula, cultural safety, and dignity. This chapter describes how Canada arrived at a state of Indigenous language devastation, then explores some promising developments in community-driven heritage language teaching, and finally presents an ecologically comprehensive strategy for Indigenous language revitalization that draws on and goes beyond the roles of formal schooling. -

Protecting Water Our Way

Protecting Water Our Way FIRST NATIONS FRESHWATER GOVERNANCE IN BRITISH COLUMBIA CONTENTS The First Nations Fisheries Council’s Water for Fish Freshwater Initiative ...............................................................1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 About this Report ...................................................................................................................................................................4 Protecting Water Our Way: Introduction ..........................................................................................................................5 Whose Water is it, Anyway? A Word on Aboriginal Water Rights ...............................................................................8 First Nations-Led Freshwater Governance and Planning in British Columbia: Five Case Stories ........................ 14 1. Yinka Dene ‘Uza’hné Water Declaration and Policy Standards ........................................................................... 15 2. Syilx Nation and siw kw (Water) Declaration and Water Responsibility Planning Methodology ................ 19 3. Water Monitoring: Gateway to Governance ...........................................................................................................25 4. Tla’amin Nation and Negotiating Shared Decision Making in the Theodosia River Watershed .................29 5. Cowichan Tribes and the -

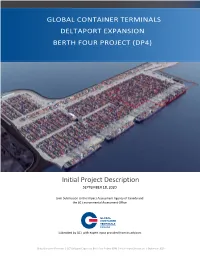

Initial Project Description SEPTEMBER 18, 2020

Initial Project Description SEPTEMBER 18, 2020 Joint Submission to the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada and the BC Environmental Assessment Office Submitted by GCT with expert input provided from its advisors Global Container Terminals | GCT Deltaport Expansion, Berth Four Project (DP4) | Initial Project Description | September 2020 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ACRONYM/ABBREVIATION DEFINITION ALR Agricultural Land Reserve AOA Archaeological Overview Assessment BC British Columbia BCEAO British Columbia Environmental Assessment Office BCI British Columbia Investment Management Corporation CAC Criteria Air Contaminants CEAA 2012 Canadian Environmental Assessment Act CEBP Coastal Environmental Baseline Program CHE Container Handling Equipment DFO Fisheries and Oceans Canada DP3 Deltaport Third Berth Project DP4 GCT Deltaport Expansion, Berth Four Project (the Project) DPW Dubai Ports World ECCC Environment Climate Change Canada ECHO Program Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation Program EMS Environmental Management System EMSP Environmental Management System Procedures EOP Environmental Operating Procedure FLNRO BC Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development FTE Full Time Equivalent Jobs GCT GCT Canada Limited Partnership GCT Deltaport Global Container Terminals Deltaport Container Terminal GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Greenhouse Gas IAA Impact Assessment Act IAAC Impact Assessment Agency of Canada IBA Important Bird Area IFM IFM Investors LED Light-Emitting Diode Global Container Terminals | GCT Deltaport -

Canadian Nuclear

Review Panel Commission d'examen Public Hearing Audience publique Roberts Bank Terminal 2 Projet du Terminal 2 à Project Roberts Bank Review Panel Commission d'examen Ms Jocelyne Beaudet Mme Jocelyne Beaudet Dr. Dave Levy M. Dave Levy Dr. Douw Steyn M. Douw Steyn Sandman Hotel Victoria Sandman Hotel Victoria 2852 Douglas Street 2852, rue Douglas Victoria, BC Victoria (C.-B.) June 13, 2019 Le 13 juin 2019 613-521-0703 StenoTran www.stenotran.com This publication is the Cette publication est un recorded verbatim compte rendu textuel des transcript and, as such, is délibérations et, en tant recorded and transcribed in que tel, est enregistrée et either of the official transcrite dans l’une ou languages, depending on the l’autre des deux langues languages spoken by the officielles, compte tenu de participant at the public la langue utilitisée par le hearing. participant à l’audience publique. Printed in Canada Imprimé au Canada 613-521-0703 StenoTran www.stenotran.com - iii - TABLE OF CONTENTS / TABLE DES MATIÈRES PAGE Presentation by 4433 Esquimalt First Nation Questions from the Panel 4450 Presentation by 4470 Scia’new First Nation Questions from the Panel 4500 Presentation by 4534 T’Sou-ke First Nation Undertakings on pages 4511 and 4528 613-521-0703 StenoTran www.stenotran.com 4430 1 Victoria, B.C. / Victoria (C.-B.) 2 --- Upon commencing on Thursday, June 13, 2019 3 at 0901 / L'audience débute le jeudi 4 13 juin 2019 à 0901 5 THE CHAIRPERSON: Good day, and 6 welcome to the third session of the second part of the 7 public hearing regarding the environmental assessment 8 of the Roberts Bank Terminal 2 Project proposed by 9 Vancouver Fraser Port Authority. -

Duncan's First Nation, and Horse Lake First Nation

SITE C CLEAN ENERGY PROJECT VOLUME 5 APPENDIX A07 PART 1 COMMUNITY SUMMARY: DUNCAN’S FIRST NATION FINAL REPORT Prepared for: BC Hydro Power and Authority 333 Dunsmuir Street Vancouver, B.C. V6B 5R3 Prepared by: Fasken Martineau 2900-550 Burrard Street Vancouver, B.C. V6C 0A3 January 2013 Site C Clean Energy Project Volume 5 Appendix A07 Part 1 Community Summary: Duncan’s First Nation Duncan’s First Nation Duncan’s First Nation (DFN) has two reserves: #151A, located 52 km west of Peace River in northwestern Alberta, and #151K, located in the McLennon/Reno area, southeast of Peace River. The majority of the population lives on #151A.1 The two reserves comprise a total area of 2426.1 ha.2 According to Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, as of December 2012, DFN has a registered population of 269, with 142 members living on DFN reserves.3 DFN has a Chief and two Councillors, and uses a custom electoral system.4 In the 1970s, DFN joined the Lesser Slave Lake Indian Regional Council. But in 1998, DFN transferred to and formed the Western Cree Tribal Council along with Horse Lake First Nations and Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation.5 DFN is also a member of the Treaty 8 First Nations of Alberta.6 Historical Background DFN are Woodland Cree and are part of the Algonquian Cree linguistic group.7 DFN adhered to Treaty 8 on July 1, 1899.8 Reserves for DFN’s use and benefit were surveyed and established in 1905, but the reserves were not confirmed by Order-in-Council until May 3, 1907, for the first eight of the reserves, and June 23, 1925 for the last two reserves.9 In the mid-1920s, Canada sought to obtain surrenders of reserve lands belonging to DFN, the Beaver Band, and the Swan River Band, the three Bands in the Lesser Slave Lake Agency.10 Between 1925 and 1927, negotiations with the Bands were conducted 1 Duncan’s First Nation. -

Ayook: Gitksan Legal Order, Law, and Legal Theory

AYOOK: GITKSAN LEGAL ORDER, LAW, AND LEGAL THEORY by Valerie Ruth Napoleon LLB, University of Victoria, 2001 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Faculty of Law © Valerie Ruth Napoleon, 2009 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee AYOOK: GITKSAN LEGAL ORDER, LAW, AND LEGAL THEORY by Valerie Ruth Napoleon LLB, University of Victoria, 2001 Supervisory Committee Dr. John Borrows, Faculty of Law Co-Supervisor Dr. John McLaren, Faculty of Law, Professor Emeritus Co-Supervisor Hamar Foster, Faculty of Law Faculty Member Dr. Michael Asch, Department of Anthropology, Professor (Limited Term) Outside Faculty Member Dr. Wendy Wickwire, Department of History, School of Environmental Studies Outside Faculty Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. John Borrows, Faculty of Law Co-Supervisor Dr. John McLaren, Faculty of Law, Professor Emeritus Co-Supervisor Hamar Foster, Faculty of Law Faculty Member Dr. Michael Asch, Department of Anthropology, Professor (Limited Term) Outside Faculty Member Dr. Wendy Wickwire, Department of History, School of Environmental Studies Outside Faculty Member Conflict is an integral and necessary aspect of human societies. The challenge is not to prevent conflict or even to resolve it, but rather, to effectively manage it so that it does not paralyse people. Historically, Gitksan society managed conflict through their legal traditions and governance practices, and I argue that it is the undermining of this conflict management system that has generated the pervasive conflicts among the Gitksan people today. -

Hedekeyeh Hots'ih Kāhidi – “Our Ancestors Are in Us”: Strengthening Our Voices Through Language Revitalization from A

Hedekeyeh Hots’ih K!hidi – “Our Ancestors Are In Us”: Strengthening Our Voices Through Language Revitalization From A Tahltan Worldview by Ed"sdi, Judith Charlotte Thompson B.Sc., Simon Fraser University, 1994 M.Sc., University of Victoria, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Interdisciplinary Studies ! Ed"sdi, Judith Charlotte Thompson, 2012 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Hedekeyeh Hots’ih K!hidi – “Our Ancestors Are In Us”: Strengthening Our Voices Through Language Revitalization From A Tahltan Worldview by Ed"sdi, Judith Charlotte Thompson B.Sc., Simon Fraser University, 1994 M.Sc., University of Victoria, 2005 Supervisory Committee Dr. Nancy J. Turner, Co-Supervisor (School of Environmental Studies) Dr. E. Anne Marshall, Co-Supervisor (Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies) Dr. Gloria J. Snively, Member (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Dr. Leslie Saxon, Member (Department of Linguistics) iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Nancy J. Turner, Co-Supervisor (School of Environmental Studies) Dr. E. Anne Marshall, Co-Supervisor (Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies) Dr. Gloria J. Snively, Member (Department of Curriculum and Instruction) Dr. Leslie Saxon, Member (Department of Linguistics) Hedekeyeh Hots’ih K!hidi – “Our Ancestors Are In Us,” describes a Tahltan worldview, which is based on the connection Tahltan people have with our Ancestors, our land, and our language. From this worldview, I have articulated a Tahltan methodology, Tahltan Voiceability, which involves receiving the teachings of our Ancestors and Elders, learning and knowing these teachings, and the sharing of these teachings with our people. -

Dispassionate Damming: Site C and the Inertia of Colonial Development

Dispassionate Destruction: Site C and the Inertia of Colonial Development Elizabeth Rudderow International Studies Senior Undergraduate Thesis Dr. Jennifer Riggan Advising May 12th, 2021 Rudderow 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION……………………...…………………………………………………….….. 3 COLONIAL DEVELOPMENT AND INDIGENOUS DISPOSSESSION….…......…………….6 A BRIEF HISTORY OF HYDROPOWER……………………………………………………...12 BIRTH OF A CONTROVERSIAL DAM…………………………………….…………………16 INTERLUDE INTO TREATY 8……………………………………………………..………….19 THE FIRST NATION FIGHT………...…………………………………………………………20 Primary positions………………………………………………………………………...21 Direct Action……………………………………………………………………………..25 Legal Disputes………………………………………………………………………...…29 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………………..…………31 REFERENCES………………………………………………………………………..…………34 Rudderow 3 INTRODUCTION In June 2016, B.C. Hydro opened an installation in the W.A.C. Bennett dam visitor center called, “Our Story, Our Voice.” The back wall of the gallery is covered in televisions which play a documentary produced by the Kwadacha Nation. The video tells the story of when B.C. Hydro destroyed an entire valley, flooding 1,761 square kilometers of forested land, and displaced hundreds of First Nation people in order to produce ‘clean’ energy. The other two walls of the gallery are covered in stenciled quotes of various sizes, the largest reading, “They call it progress, we call it destruction.” B.C. Hydro claims that the installation gives First Nations a chance to share their story and begin to heal. Meanwhile, just 120 km down that very same river, the province-owned energy company was beginning construction of the Site C Hydroelectric project against the explicit consent of West Moberly and Prophet River First Nations. “The 1960s were a different time,” claims B.C. Hydro, while giving ample evidence to the contrary (“First” 2016). Hydropower is heralded by supporters for being a clean source of energy which is part of a promising energy future.