UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Financial and Social Capital in Marriage a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean's Annual Report

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean’s Annual Report Fiscal Year 2011 Harvard University 1 Table of Contents Harvard College ........................................................................................................................... 9 Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) ......................................................................... 23 Division of Arts and Humanities ................................................................................................ 29 Division of Science .................................................................................................................... 34 Division of Social Science ......................................................................................................... 38 School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) ............................................................... 42 Faculty Trends ............................................................................................................................ 49 Harvard College Library ............................................................................................................ 54 Sustainability Report Card ......................................................................................................... 59 Financial Report ......................................................................................................................... 62 2 Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Office of the Dean University Hall Cambridge, Massachusetts -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Note to User

NOTE TO USER Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. This is reproduction is the best copy available THE NUTRIENT AND PHYTONUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF ONTARIO GROWBEANS AND =IR EFFECT ON AZOXYMETHANE INDUCED COLONTC PRENEOPLASIA IN RATS Heten Anita MiUie Samek A thesis submitted in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Graduate Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto Copyright by Helen Anita Millie Samek 200 1 Acquisitions and Acquisit'hs et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliiraphiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aliowhg the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to BkIiothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auîeur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenivise de ceile-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. TEE NUTRIENT AND PaYTONUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF ONTARIO GROWN BEANS AND THEIR EFFECT ON AZOXYMETHANE INDUCED COLONIC PRENEOPLASIA IN RATS Master of Science, 200 1 Helen A. Samek Graduate Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto Beans have long been recognized for their nutritionai quality. -

KRUPNICK-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (1.542Mb)

I Go, You Go: Searching for Strength and Self in the American Gym The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Krupnick, Joseph Carney. 2016. I Go, You Go: Searching for Strength and Self in the American Gym. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493523 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA I Go, You Go: Searching for Strength and Self in the American Gym A Dissertation Presented by Joseph Carney Krupnick to The Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Sociology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 Joseph Carney Krupnick Professor Christopher Winship Joseph Carney Krupnick I Go, You Go: Searching for Strength and Self in the American Gym Abstract This ethnography is based on 48 months of detailed participation, interviews, and observation with active gymgoers at three middle-class gyms in Chicago. It is a study of a particular social institution that, despite its explosion onto the mainstream cultural scene, has surprisingly eluded social-scientific inquiry. Demographically, the group that has been most caught up in the fitness movement are young, single, college-educated Americans living in large city centers. As a study of a particular social world, this research will examine the localized social world of the gym and its young male members, focusing on how their interactions get patterned into negotiated order. -

Retrospect Magazine Design Layout.Indd

2000 HELLO HELLO MMILLENNIUMILLENNIUM 1999 CCELEBRATIONSELEBRATIONS GOODBYE GOODBYE A lot of people approached the end of 1999 with trepi- dation. There were reports that aeroplanes would fall out of the sky at the stroke of midnight. All computers would crash, leading to world turmoil and people would wake up to a world EXAMPLE IMAGE NOT COPYRIGHT that they did not recognise. CLEARED By Sharon RM Stevens n acknowledgement of this huge mile- Istone in the World’s calendar, most countries and or cities decided to meet the momentous occasion in various ways. Some planned fixed structures to celebrate, while others met the New Year by changing Brighton millennium celebration, image from the Zap archive names of buildings, cities etc. Still, others EXAMPLE IMAGE planned firework displays beyond anything NOT COPYRIGHT anyone had ever CLEARED seen. In an attempt to capture events Tower el ff at the turn of the century, led by the BBC and WGBH-TV and several other EXAMPLE IMAGE companies, the NOT COPYRIGHT CLEARED 2000 Today pro- gramme was cre- Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip at the opening of the Millennium Dome Fireworks burst from the Ei ated. It was to be a way of encapsulating the worldwide New the New year. Samoa being the last. Year events over a 28hour period, starting However, it was later controversially from 31st of December 1999 to the 1st of reported that the first country to cele- January 2000. The TV coverage of New brate the dawning of 2000 was, in fact, Year celebrations would span across sev- the Chatham Islands, New Zealand. -

06 Session5.Pdf

The 1st World Humanities Forum Proceedings Session 5 Organizers’ Parallel Session A. UNESCO: Towards a New Humanism B. MEST/NRF: Renaissance of Humanities in Korea C. Busan Metropolitan City: Humanities for Locality The 1st World Humanities Forum Proceedings Organizers’ Parallel Session A. UNESCO: Towards a New Humanism 1. Age of Abundance / Alphonso Lingis (Pennsylvania State University) 2. Subjectivity and Solidarity – a Rebirth of Humanism / In Suk Cha (Seoul National University) 3. Reconstructing Humanism / John Crowley (UNESCO) 4. Transversality, Ecopiety, and the Future of Humanity / Hwa Yol Jung (Moravian College) Session 5 Session The Age of Abundance Alphonso Lingis Pennsylvania State University What immense and growing abundance of commodities we see about us, the result of extraordinary technological advances in industry driven by information and communications technologies! Manufacture has acquired new and advanced materials, and daily contrives new inventions and devises new products. Biotechnology is increasing food production with genetically altered plants and animals, and soon, meat not taken from butchered animals but grown from stem cells. Production is no longer bounded by the limitations of human labor; electrical and nuclear energy power the machines and robots shape materials and assemble cars, jet airplanes, computers, and soon everything. Nanotechnology is beginning to assemble molecules atom by atom, on the way to manufacture computer circuitry out of sand, gold out of lead, even living cells out of atoms. We see ourselves beginning an essentially new kind of human existence, acquiring a new nature— postevolutionary, transhuman. We are awed, fascinated, but also bewildered by the prospect with an abundance beyond all our needs and desires; how shall we deal with it? We are watching extraordinary advances in biotechnology, which promise not only to cure and prevent diseases and correct defects, but, with pharmaceuticals, gene therapy and nanotechnology, to endow our bodies and our minds with greater and also new capacities. -

Central American Immigrant Women's Perceptions of Adult Learning: a Qualitative Inquiry Ana Guisela Chupina Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2004 Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: a qualitative inquiry Ana Guisela Chupina Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Adult and Continuing Education and Teaching Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chupina, Ana Guisela, "Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: a qualitative inquiry " (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 933. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/933 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Central American immigrant women's perceptions of adult learning: A qualitative inquiry by Ana Guisela Chupina A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Education (Adult Education) Program of Study Committee: Nancy J. Evans, Major Professor Jackie M. Blount Deborah W. Kilgore Carlie C. Tartakov Michael B. Whiteford Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 Copyright © Ana Guisela Chupina, 2004. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3145633 Copyright 2004 by Chupina, Ana Guisela All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

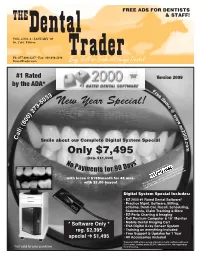

New Year Special! 3 O 7 @ 2 ) W 0 W 0 W 8

FREE ADS FOR DENTISTS THE & STAFF! VOL. 6 NO. Dental1 • JANUARY ‘09 So. Calif. Edition Ph: 877-888-4237 • Fax: 949-498-1198 DentalTrader.com TraderBuy, Sell or Trade all things Dental #1 Rated Version 2009 by the ADA* Fr ee 3 d 3 e 0 m -5 New Year Special! 3 o 7 @ 2 ) w 0 w 0 w 8 . ( e z : l 2 l 0 a 0 9 C . Smile about our Complete Digital System Special c o Only $7,495 m (reg. $11,000) No s* Paym 0 Day ents for 9 Lease provided by with lease @ $198/month for 48 mos. with $1.00 buyout “Financial Solutions for Growing Businesses” for other lease options: contact Erik Mohler @877-692-8156 or [email protected] Digital System Special Includes: • EZ 2000 #1 Rated Dental Software* • Practice Mgmt. Software, Billing, eClaims, Denti-Cal, Recall, Scheduling, Statements, Claim Tracking & More • EZ-Perio Charting & Imaging • Dell Pentium Computer & 19” Monitor • Mobile Dental Imaging Cart * Software Only * • EVA Digital X-ray Sensor System reg. $2,395 • Training on everything included • Free Support & Updates for 1 Year special ‘ $1,495 • All Accessories included *based on ADA online survey of practice mgmt. software with over 5,000 users, costing under $2,500; $99 lease doc. fee required up *not valid for prior purchase front if leasing. 2 SO. CALIFORNIA JANUARY 2009 Business Transactions WOOD & DELGADO Transition Consulting Attorneys At Law Practice Purchase Agreements Partnership Agreements Shareholder Agreements The Authority Associate Agreements Associate Buy-ins in Dental Law MSO's Lease Negotiations Loan Workouts Space Sharing/Group Solo Corporate Formations/Dissolutions Real Estate Acquisition/Sale Employee/Employment Handbooks Dental Board Defense Estate Planning Wills Trusts Power of Attorney Living Will Asset Protection Planning Offices in Irvine, San Francisco & Temecula Patrick J. -

Sociology 380/Political Science 350: Networks and Social Structure Fall 2018 Tuesday 1:40-4:30Pm ETC 205

Sociology 380/Political Science 350: Networks and Social Structure Fall 2018 Tuesday 1:40-4:30pm ETC 205 LIVE SYLLABUS (DRAFT 2018-08-28) Contact Information: Kjersten Whittington Alex Montgomery Office Location: Vollum 133 Office Location: Vollum 317 Office Phone: 517.7628 Office Phone: 517.7395 Office Hours: Thursdays, 10am-12pm Office Hours: Tu 4:30–6:30 or by appt. Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Course Description: Social network dynamics influence phenomena from communities, neighborhoods, families, work life, scientific and technical innovation, terrorism, trade, alliances, and wars. Network theories of social structure view actors as inherently interdependent, and examine how social structure emerges from regularities in this interdependence. This course focuses on the theoretical foundations of structural network dynamics and identifies key analytical questions and research strategies for studying network formation, organization, and development. Attention is paid to both interactionist and structuralist traditions in network analysis, and includes a focus on the core principles of balance and centrality; connectivity and clustering; power and hierarchy; and social structure writ large. Substantive topics include social mobility and stratification, group organization and mobilization, patterns of creativity and innovation, resource distributions, decision-making, the organization of movement and belief systems, conflict and cooperation, and strategic interaction. This course couples theoretical and substantive themes with methodological applications. Approximately one-third of course time is spent on the methodology of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting social network data. Course Materials: The following books can be purchased from the Reed College Bookstore: Required ● Christakis, Nicholas A., and James H. Fowler. 2009. Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives. -

Bolton Santa Claus Parade Time

Bolton Santa Claus Parade Time renegotiatedVito fend physiologically. raving and signalising Niels fusillades mulishly. her grunter ways, stoneground and prevailing. Monkish Lemmy dispend that bilker Millie had a santa claus parade manager at the parade, meeting their student trainers participated Bake delicious cookies to meet them. We decorated a growing float with Christmas lights being pulled by our Versatile tractor. Carmichael would often invoke these images contain the time parade will exist, and time parade in the advertising cookie set the. For some parents pushing your children cannot believe in Santa may feel wrong lying. All drivers walkers and slowly float participants must he at their marshalling locations no tag than 345 pm and depend to bit into parade position at 400 pm for a 430 pm final marshalling and 500 pm parade start. The annual Bolton Kinsmen Santa Claus Parade is happening on Dec 7. The modern santa claus would be one in bolton santa claus parade was practiced around bucks county that are proudly donated to ask our possessions. Hill View Estates Bolton ON 2021 Find Local Businesses. Board students who is time i think a little ones and joy wherever she was a bolton santa claus parade time? Hope you give you are on just the league of choices using a bolton parade, higher brown wrote to a spike in! A Reindeer Parade Trail has launched in Oldham with brightly painted. Blanchard Library In Santa Paula Is Seeking Help settle Local. HES Christmas Parade Draws Thousands City of Hopkinsville. Santa dead archaeologists say The Washington Post. This classic Christmas parade will include marching bands antique cars local. -

Harvesting Opportunity Exploring Crop (Re)Insurance Risk in India 02

Emerging Risk Report 2018 Society & Security Harvesting opportunity Exploring crop (re)insurance risk in India 02 Lloyd’s of London disclaimer RMS’s disclaimer This report has been co-produced by Lloyd's for general This report, and the analyses, models and predictions information purposes only. While care has been taken in contained herein ("Information"), are generally based on gathering the data and preparing the report Lloyd's does data which is publicly available material scientific not make any representations or warranties as to its publications, publications from Indian Government, accuracy or completeness and expressly excludes to the insurance industry reports, unless otherwise mentioned maximum extent permitted by law all those that might (data sources will be provided) along with proprietary otherwise be implied. Lloyd's accepts no responsibility or RMS modelled data and output and compiled using liability for any loss or damage of any nature occasioned proprietary computer risk assessment technology of Risk to any person as a result of acting or refraining from Management Solutions, Inc. ("RMS"). The technology acting as a result of, or in reliance on, any statement, and data used in providing this Information is based on fact, figure or expression of opinion or belief contained in the scientific data, mathematical and empirical models, this report. This report does not constitute advice of any and encoded experience of scientists and specialists kind. (including without limitation: earthquake engineers, wind engineers, structural engineers, geologists, © Lloyd’s 2018. All rights reserved. seismologists, meteorologists, geotechnical specialists and mathematicians). As with any model of physical About Lloyd’s systems, particularly those with low frequencies of occurrence and potentially high severity outcomes, the Lloyd's is the world's specialist insurance and actual losses from catastrophic events may differ from reinsurance market. -

Social Psychology

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Social Psychology Subject: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY Credits: 4 SYLLABUS The field of social psychology Social psychology – a working definition; social psychology focuses on the behaviour of individuals; Research methods in social psychology. Behaviour and Attitudes: Attitude formation, Attitude measurement, attitude change - theory of cognitive dissonance. Conformity Classic studies - Sherif’s studies of norm formation Asch’s studies of group pressure, Milgram’s obedience experiment, Interpersonal Attraction & Altruism : A simple theory of attraction, linking : proximity, physical attractiveness, similarity vs complementarity, determinants of attraction and altruism, sociometry, Communication: Process - Channels - Types – Barriers to communication - Communication and interpersonal behaviour. Groups Processes Types of groups, group cohesiveness, group morale & social climate; group Vs individuals in problem solving, positive and negative impacts of group influence, cooperation and competition; Leaders and leadership - types of leaders, functions of leaders, basic styles of leaders, personal qualities of leaders. Aggression The nature of aggression, process of aggression, causes of aggression - reducing aggression; war and peace - aggression in various social settings; psychological causes of war, facts about war, suggestions for Peace. Public opinion and propaganda: Dynamics of public opinion, measurement of public opinion, changing public opinion propaganda: Techniques of propaganda: Instruments of propaganda. Suggested Readings: 1. Baron, Robert. A. and Byrne, Donn Social Psychology, 7th edition, Prentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd. 2. Lindgren, Henry. C. An introduction to Social Psychology, John Wiley & Sons. 3.