By Clara S. Lewis B.A., 2003, Smith College a Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

October 22, 2014

SYMPOSIUM ON JOURNALISTIC COURAGE October 22, 2014 The McGill program is funded by the McGill Lecture Endowment. SYMPOSIUM ON JOURNALISTIC COURAGE Excerpts from four group discussions: Ferguson, Missouri: When conflicts come home The NFL beat: Exposing the ills in America’s favorite sport The courage to ask tough questions Face-to-face with Ebola: A reporter’s perspective This report was written by Carolyn Crist October 22, 2014 The McGill program is funded by the McGill Lecture Endowment. Contents Welcome .............................................................................. 3 Ferguson, Missouri: When conflicts come home ...................... 4 The NFL beat: Exposing the ills in America’s favorite sport ....... 7 The courage to ask tough questions ......................................10 Face-to-face with Ebola: A reporter’s perspective ...................13 Participants ..........................................................................19 Contact us ...........................................................................19 Photos by Sarah Freeman, unless noted 2 Welcome John F. Greenman: On behalf of my colleagues in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, welcome to the McGill Symposium. The McGill Symposium, now in its eighth year, is an outgrowth of the McGill Lecture. For 36 years, the McGill Lecture has brought significant figures in journalism to the University of Georgia to help us honor Ralph McGill’s courage as an editor. The McGill Symposium brings together students, faculty and leading journalists -

Here, I Would Encourage You to Explore Our Great City, Taste Our Authentic Cuisines and Most Importantly - Have Fun with Your Colleagues Here in St

OFFICE OF THE MAYOR CITY OF ST. LOUIS MISSOURI Dear Carol, On behalf of the entire City of St. Louis, we welcome the National Association of Black Journalists Region II Conference. I hope the conference attendees will enjoy all the wonderful attractions, neighborhoods, and cultural institutions that St. Louis offers. I am excited for the local voices and stories that will be a part of the conference’s conversations. Today is certainly an exciting time to work in journalism and communications. With the ever-changing media landscape, new platforms, major news stories, and the upcoming presidential election, quality reliable journalism and reporting have never been more important to communities and governments. With that mission, it is so important that fellow journalism practitioners meet, discuss, and learn. I am encouraged by this year’s conference theme, “Telling Our Story.” Thank you for engaging with and telling local and national stories that impact the African American community today. Thank you for choosing St. Louis for your conference. I appreciate the work of conference chair Sharon Stevens and the local planning committee for making this conference a success. Sincerely, Lyda Krewson Mayor, City of St. Louis OFFICE OF THE COUNTY EXECUTIVE CITY OF ST. LOUIS MISSOURI Dear Friends: I am pleased to welcome you to the 2020 National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) Region II Conference hosted by The Greater St. Louis Association of Black Journalists (GSLABJ). The conference will provide a wonderful oppoiiunity to engage in conversations with local and national expe1is on an array of significant issues in journalism today. I commend the efforts of the GSLABJ in their efforts to bring the NABJ Region II Conference to St. -

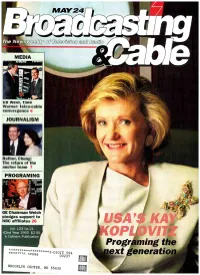

Ext Generatio

MAY24 The News MEDIA nuo11011 .....,1 US West, Time Warner: telco-cable convergence 6 JOURNALISM Rather, Chung: The return of the anchor team PROGRAMING GE Chairman Welch pledges support to NBC affiliates 26 U N!'K; Vol. 123 No.21 62nd Year 1993 $2.95 A Cahners Publication OP Progr : ing the no^o/71G,*******************3-DIGIT APR94 554 00237 ext generatio BROOKLYN CENTER, MN 55430 Air .. .r,. = . ,,, aju+0141.0110 m,.., SHOWCASE H80 is a re9KSered trademark of None Box ice Inc. P 1593 Warner Bros. Inc. M ROW Reserve 5H:.. WGAS E ALE DEMOS. MEN 18 -49 MEN 18 -49 AUDIENCE AUDIENCE PROGRAM COMPOSITION PROGRAM COMPOSITION STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE 9 37% WKRP IN CINCINNATI 25% HBO COMEDY SHOWCASE 35% IT'S SHOWTIME AT APOLLO 24% SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE 35% SOUL TRAIN 24% G. MICHAEL SPORTS MACHINE 34% BAYWATCH 24% WHOOP! WEEKEND 31% PRIME SUSPECT 24% UPTOWN COMEDY CLUB 31% CURRENT AFFAIR EXTRA 23% COMIC STRIP LIVE 31% STREET JUSTICE 23% APOLLO COMEDY HOUR 310/0 EBONY JET SHOWCASE 23% HIGHLANDER 30% WARRIORS 23% AMERICAN GLADIATORS 28% CATWALK 23% RENEGADE 28% ED SULLIVAN SHOW 23% ROGGIN'S HEROES 28% RUNAWAY RICH & FAMOUS 22% ON SCENE 27% HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 22% EMERGENCY CALL 26% SWEATING BULLETS 21% UNTOUCHABLES 26% HARRY & THE HENDERSONS 21% KIDS IN THE HALL 26% ARSENIO WEEKEND JAM 20% ABC'S IN CONCERT 26% STAR SEARCH 20% WHY DIDN'T I THINK OF THAT 26% ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK 20% SISKEL & EBERT 25% LIFESTYLES OF RICH & FAMOUS 19% FIREFIGHTERS 25% WHEEL OF FORTUNE - WEEKEND 10% SOURCE. NTI, FEBRUARY NAD DATES In today's tough marketplace, no one has money to burn. -

The U.S. Broadcast News Media As a Social Arena in the Global Climate Change Debate

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2007 The .SU . broadcast news media as a social arena in the global climate change debate Adam Jeremy Kuban Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kuban, Adam Jeremy, "The .SU . broadcast news media as a social arena in the global climate change debate" (2007). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15479. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15479 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The U.S. broadcast news media as a social arena in the global climate change debate by Adam Jeremy Kuban A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Program of Study Committee: Jeff Blevins, Major Professor Lulu Rodriguez Eugene Takle Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2007 Copyright © Adam Jeremy Kuban, 2007. All rights reserved. 2009 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Past studies on public knowledge and information sources 3 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 6 The rise and fall of media coverage of scientific issues 6 National versus international triggering events 9 The social arena theory 10 Research questions 18 CHAPTER 3. -

2006-2007 Impact Report

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2006–2007 Annual Report From the IWMF Executive Director and Co-Chairs March 2008 Dear Friends and Supporters, As a global network the IWMF supports women journalists throughout the world by honoring their courage, cultivating their leadership skills, and joining with them to pioneer change in the news media. Our global commitment is reflected in the activities documented in this annual report. In 2006-2007 we celebrated the bravery of Courage in Journalism honorees from China, the United States, Lebanon and Mexico. We sponsored an Iraqi journalist on a fellowship that placed her in newsrooms with American counterparts in Boston and New York City. In the summer we convened journalists and top media managers from 14 African countries in Johannesburg to examine best practices for increasing and improving reporting on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. On the other side of the world in Chicago we simultaneously operated our annual Leadership Institute for Women Journalists, training mid-career journlists in skills needed to advance in the newsroom. These initiatives were carried out in the belief that strong participation by women in the news media is a crucial part of creating and maintaining freedom of the press. Because our mission is as relevant as ever, we also prepared for the future. We welcomed a cohort of new international members to the IWMF’s governing board. We geared up for the launch of leadership training for women journalists from former Soviet republics. And we added a major new journalism training inititiative on agriculture and women in Africa to our agenda. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

Fresh Dressed

PRESENTS FRESH DRESSED A CNN FILMS PRODUCTION WORLD PREMIERE – DOCUMENTARY PREMIERE Running Time: 82 Minutes Sales Contact: Dogwoof Ana Vicente – Head of Theatrical Sales Tel: 02072536244 [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS With funky, fat-laced Adidas, Kangol hats, and Cazal shades, a totally original look was born— Fresh—and it came from the black and brown side of town where another cultural force was revving up in the streets to take the world by storm. Hip-hop, and its aspirational relationship to fashion, would become such a force on the market that Tommy Hilfiger, in an effort to associate their brand with the cultural swell, would drive through the streets and hand out free clothing to kids on the corner. Fresh Dressed is a fascinating, fun-to-watch chronicle of hip-hop, urban fashion, and the hustle that brought oversized pants and graffiti-drenched jackets from Orchard Street to high fashion's catwalks and Middle America shopping malls. Reaching deep to Southern plantation culture, the Black church, and Little Richard, director Sacha Jenkins' music-drenched history draws from a rich mix of archival materials and in-depth interviews with rappers, designers, and other industry insiders, such as Pharrell Williams, Damon Dash, Karl Kani, Kanye West, Nasir Jones, and André Leon Talley. The result is a passionate telling of how the reach for freedom of expression and a better life by a culture that refused to be squashed, would, through sheer originality and swagger, take over the mainstream. 2 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS SACHA JENKINS – Director Sacha Jenkins, a native New Yorker, published his first magazine—Graphic Scenes & X-Plicit Language (a ‘zine about the graffiti subculture)—at age 17. -

21860:21860.Qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1 21860:21860.Qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 2 21860:21860.Qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1

21860:21860.qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1 21860:21860.qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 2 21860:21860.qxd 6/14/10 3:57 PM Page 1 NAHJ EN DENVER EL GRITO ACROSS THE ROCKIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Message from NAHJ President ..........................................................................................................................................2 Welcome Message from the 2010 Convention Programming Co-Chairs...........................................................................................5 Welcome Message from the 2010 Convention Co-Chairs ...............................................................................................................6 Welcome Message from the Mayor of Denver .................................................................................................................................7 Mission of NAHJ ..............................................................................................................................................................................9 Why NAHJ Exists ............................................................................................................................................................................11 Board of Directors ..........................................................................................................................................................................13 Staff ...............................................................................................................................................................................................15 -

{PDF EPUB} Pinstriped Summers Memories of Yankee Seasons Past by Dick Lally Lally, Richard

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Pinstriped Summers Memories of Yankee Seasons Past by Dick Lally Lally, Richard. PERSONAL: Married Barbara Bauer (a writer; divorced). ADDRESSES: Agent —c/o Author Mail, Random House/Crown, 1745 Broadway, New York, NY 10019. CAREER: Sportswriter. WRITINGS: (With Bill Lee) The Bartender's Guide to Baseball , Warner Books (New York, NY), 1981. (With Bill Lee) The Wrong Stuff , Viking (New York, NY), 1984. Pinstriped Summers: Memories of Yankee Seasons Past , Arbor House (New York, NY), 1985. Chicago Clubs (collectors edition), Bonanza Books (New York, NY), 1991. Boston Red Sox (collectors edition), Bonanza Books (New York, NY), 1991. (With Joe Morgan) Baseball for Dummies , foreword by Sparky Anderson, IDG Books Worldwide (Foster City, IA), 1998. (With Joe Morgan) Long Balls, No Strikes: What Baseball Must Do to Keep the Good Times Rolling , Crown (New York, NY), 1999. Bombers: An Oral History of the New York Yankees , Crown (New York, NY), 2002. (With Bill Lee) Have Glove, Will Travel: The Adventures of a Baseball Vagabond , Crown (New York, NY), 2005. SIDELIGHTS: Sports writer Richard Lally focusses much of his efforts on his main passion: baseball. After collaborating with former pro player Bill Lee on Lee's autobiography, The Wrong Stuff , Lally wrote Pinstriped Summers: Memories of Yankee Seasons Past , a book that focuses on the team's history from the time the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) bought the team in 1965 until the 1982 season. During this period, the Yankees experienced great success, winning four American League pennants and two World Series. They also experience "down" years, including a last-place finish in 1966. -

The Jewish Defense League

The Jewish Defense League This document is an archived copy of an older ADL report and may not reflect the most current facts or developments related to its subject matter. About the Jewish Defense League The Jewish Defense League, also known as JDL, was established in 1968 for the declared purpose of protecting Jews by whatever means necessary in the face of what was seen by the group’s principals as their dire peril. The founder, national chairman and leader of the JDL was a then-38-year-old ordained rabbi from Brooklyn, New York, Meir Kahane, who, in 1990, was assassinated in New York by an Arab extremist. In Rabbi Kahane’s gross distortion of the position of Jews in America, American Jews were living in a fiercely hostile society, facing much the same dangers as the Jews in Nazi Germany or those in Israel surrounded by 100-million Arab enemies. Rabbi Kahane believed that the major Jewish organizations in the United States had failed to protect America’s Jews from anti-Semitism, which he saw as “exploding” all over the country. "If I have succeeded in instilling fear in you," Rabbi Kahane said in the closing statement of his standard speech, "I consider this evening a success." In fact, Kahane consistently preached a radical form of Jewish nationalism which reflected racism, violence and political extremism. In Their Own Words Irv Rubin -- Chairman of the Jewish Defense League 1 / 36 After the attack on the Jewish community center in Los Angeles: "Those kids at that community center were sitting ducks. -

The Murder of Alex Odeh

The Link www.ameu.org Page 1 Published by Americans for The Link Middle East Understanding, Inc. Volume 49, Issue 3 Link Archives: www.ameu.org June-July 2016 9 a.m., Oct. 11, 1985: a bomb explodes at the Santa Ana office of the American- Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee. Shortly after the attack, the suspected terrorists flee to Israel to avoid U.S. jurisdiction. About This Issue 30 years later, no one has been named, questioned or indicted for The Murder of Alex Odeh by Richard Habib The Link www.ameu.org Page 2 Alex Doc. Pix AMEU About This Issue: Board of Directors ur July-August 1989 issue of Jane Adas, President The Linkp. featured 2 an interview Elizabeth D. Barlow with Ellen Nassab, the sister Henry Clifford Oof Alex Odeh. That interview took Edward Dillon place on Feb. 18, 1989 at Ellen’s home in Protestantism’s Embrace of Zionism Rod Driver John Goelet California, less than four months before Richard Hobson, Treasurer she died of cancer. Anne R. Joyce, Vice President Brian Mulligan In that interview Ellen cited a L.A. Daniel Norton Times article that named a member of Hon. Edward L. Peck the Jewish Defence League as a suspect Donald L. Snook in her brother’s murder. But that suspect Thomas Suarez had fled to Israel, and Israeli authorities James M. Wall had refused to extradite him back to the Link author Richard Habib President-Emeritus States. Ellen’s last words on the subject Robert L. Norberg were: “So, here in the States, we bow to our Comment application.