Melbourne, 8 June 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Broadcasting Foundation Annual Report 2016

Community Broadcasting Foundation Annual Report 2016 Snapshot 2015.16 500 $200M 24,600 Licensed community owned and The Community Broadcasting Foundation has given more operated broadcasting services making than $200M in grants since 1984. Volunteers involved in community broadcasting Australia's community broadcasting largest independent media sector. 230 70% 5,800 This year the Community Broadcasting 70% of community radio and television People trained each year in Foundation allocated 617 grants totaling services are located in regional, rural media skills, leadership skills $ $15,882,792 to 230 organisations. and remote areas. The median income and digital literacy. at regional and rural stations is $52,900. 42% of regional and rural stations are 605M wholly volunteer operated. With a turnover of over $120m and the economic value of its volunteer effort estimated at $485m per annum, the community broadcasting sector makes a significant contribution to the 78% 8,743 Australian economy. 78% of all community radio broadcast 8,743 hours of specialist programming in an average week time is local content. Local news and information is the primary reason Australians listen to community radio. Religious Ethnic + RPH Cover: 100.3 Bay FM broadcaster Hannah Sbeghen. This photo taken 5M Indigenous by Sean Smith won the Exterior/ 27% of Australians aged over Interior category in the CBF’s Focus 15 listen to community radio in an LGBTIQ on Community Broadcasting Photo average week. 808,000 listen exclusively Competition. to community radio. 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 Community Broadcasting Foundation Annual Report 2016 1 Success Stories Leveraging support to expand Success broadcast range Coastal FM broadcasts to the Stories northwest coast of Tasmania, with the main transmitter located The increase in phone in Wynyard and additional calls and visits to our transmitter sites in Devonport and Smithton. -

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

2019-Information-Book-V1.Pdf

The information in this booklet is presented to give parents an appreciation of the objectives and operations of the Australian Boys Choir. If you wish to know more, you are invited to contact a member of staff or the ABCI Board. Contents Contact Details .............................................................................................. 4 Child Safety ................................................................................................... 5 Key People .................................................................................................... 7 A Brief History ................................................................................................ 8 Organisation and Management ...................................................................... 8 Staff ............................................................................................................. 10 The Training Program .................................................................................. 14 Rehearsals .................................................................................................. 16 Weekend Workshops ................................................................................... 18 Summer Music School ................................................................................. 18 Attendance Requirements ........................................................................... 19 Tours .......................................................................................................... -

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

Target's Statement: Off-Market Takeover Offer by Nine Entertainment Co

MRN TARGET'S STATEMENT: OFF-MARKET TAKEOVER OFFER BY NINE ENTERTAINMENT CO. HOLDINGS LIMITED Sydney, Friday 13 September 2019: Macquarie Media Limited (ASX: MRN) (MML) refers to the announcement by Nine Entertainment Co. Holdings Limited (ASX:NEC) (Nine) on 12 August 2019 regarding a conditional off-market takeover offer for all of the ordinary shares of MML (Offer). MML confirms that its Target's Statement in relation to the Offer and accompanying Independent Expert's Report (Target's Statement) was issued today. A copy of the Target’s Statement is enclosed. Despatch of the Target's Statement to shareholders also occurred today and copies will also be provided to Nine and lodged with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission today. For further information contact: Lisa Young Company Secretary Macquarie Media Limited Email: [email protected] - ENDS- MACQUARIE MEDIA LIMITED ABN 32 063 906 927 Target's Statement in response to the offer by Fairfax Media Limited (an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of Nine Entertainment Co. Holdings Limited) to acquire all of your MRN Shares The Independent Directors of MRN unanimously recommend that, in the absence of a superior proposal and subject to the independent expert continuing to opine that the Offer is reasonable, you ACCEPT the Offer to purchase all of your MRN Shares for $1.46 cash per MRN Share. The Independent Expert has concluded that the Offer is fair and reasonable to MRN Shareholders. This is an important document and requires your immediate attention. If you are in doubt as to how to deal with this document, you should consult your financial or other professional adviser immediately. -

Hazard (Edition No

Hazard (Edition No. 25) V.I.S.S. December 1995 Victorian Injury Surveillance System Monash University Accident Research Centre Translating injury surveillance to prevention: an update As VISS is moving to a new system of data collection in 1996 it is timely to review our achievements over the past eight years. This edition of Hazard highlights some VISS success stories and outlines some of the challenges that face us in 1996 and beyond. Erin Cassell or more significant injury issues and progress has been made by VISS and Virginia Routley Joan Ozanne-Smith a discussion of actions that need to be other bodies but where there is good taken to reduce or eliminate the potential for further gains. In these Summary potential for injury. areas a modest increase in human and financial resources applied to the The first edition of Hazard was As background to this (the 25th) problem could be repaid by significant published in July 1988, the year in edition of Hazard, progress on all the reductions in the number and/or the which the Victorian Injury recommendations to reduce injuries severity of injuries. Surveillance System was established. made in Hazard was reviewed. The The quarterly publication of Hazard review not only covered follow-up Enclosed in this edition is a client is one of the major methods VISS action undertaken by VISS alone or in survey. In 1995 VISS received a uses to disseminate information. The collaboration with other Monash small grant from the Victorian selection of topics forHazard is based University Accident Research Centre Health Promotion Foundation to on the relative severity, frequency (MUARC) projects but also included support the implementation of and the potential preventability of significant action on VISS findings from VISS data analyses injury problems that emerge from recommendations taken by other and research. -

Download Annual Report 2015-2016

Australian Vietnamese Women’s Association Inc. Hội Phụ Nữ Việt Úc Serving the Community since 1983 Annual Report 2015-2016 AUSTRALIAN VIETNAMESE WOMEN’S ASSOCIATION INC. Activity Chart as at June 30th, 2016 Committee of Management 2015-2016 Contents Contents 1 Acknowledgements 2 A message from our President 3 Treasurer’s Report 4 Richmond Seniors’Group 4 A message from our Secretary and Chief Executive Officer 5 Home Care Packages Program - Southern & Western Region 6 Home Care Packages Program - Northern & Eastern Region 8 Planned Activity Groups (PAGs) 10 Home Safety for Elderly People 12 Preventing Family Violence Against Women 12 Sustainable Living 13 Connecting Me 14 Diabetes Awareness 15 Training 16 Illicit Drug and Alcohol Treatment Counselling Project 17 Parallel Learning Playgroups 18 Vietnamese Prisoners Support Program 20 Gambling Counselling 22 Gambling Prevention 23 Richmond Tutoring Program 24 Media and Information Technology 25 3ZZZ - 92.3 FM, Vietnamese Language Radio Program 26 2015-16 | Annual Report Association Inc. Women’s Vietnamese Australian Richmond Monday Group 26 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 27 Statement of Financial Position 28 Independent Auditor’s Report 29 Volunteer and Student Placements 31 Acknowledgements 32 the community community 1 Acknowledgements 18 YEARS OF SERVICE Hong Nguyen as 3ZZZ Radio Program Team Leader 16 YEARS OF SERVICE Kim Vu 15 YEARS OF SERVICE Thao Ha, Nam Nguyen 10 YEARS OF SERVICE Australian Vietnamese Women’s Association Inc. | Annual Report 2015-16 | Annual Report Association Inc. Women’s Vietnamese Australian Huy Luu, Quynh Huong Nguyen Yvonne Tran, Bac Thi Nguyen 5 YEARS OF SERVICE Hoa Trinh, Tania Huynh, Thi Kim Chi Nguyen Thu Trang Ly, Phao Phi Pham Trinh Mong Chau, Thuan Thanh Thi Doan Thank you for your loyal service November 2016 2 the community community A message from our President Dear AVWA Members, Associates and Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, it is my honor and pleasure to report to you the accomplishments of AVWA during the 2015-2016 financial year. -

COMMERCIAL RADIO AWARDS (Acras) Please Note: Category Finalists Are Denoted with the Following Letters: Country>Provincial>Non-Metropolitan>Metropolitan

FINALISTS FOR 2016 AUSTRALIAN COMMERCIAL RADIO AWARDS (ACRAs) Please note: Category Finalists are denoted with the following letters: Country>Provincial>Non-Metropolitan>Metropolitan BEST ON-AIR TEAM – METRO FM Kate, Tim & Marty; Kate Ritchie, Tim Blackwell & Marty Sheargold, Nova Network, NOVA Entertainment M The Kyle & Jackie O Show; Kyle Sandilands & Jackie Henderson, KIIS 106.5, Sydney NSW, Australian Radio Network M The Hamish & Andy Show; Hamish Blake & Andy Lee, Hit Network, Southern Cross Austereo M Jonesy & Amanda; Brendan Jones & Amanda Keller, WSFM , Sydney NSW, Australian Radio Network M Fifi & Dave; Fifi Box & Dave Thornton, hit101.9 Fox FM, Melbourne VIC, Southern Cross Austereo M Chrissie, Sam & Browny; Chrissie Swan, Sam Pang & Jonathan Brown, Nova 100, Melbourne VIC, NOVA Entertainment M BEST ON-AIR TEAM – METRO AM FIVEaa Breakfast; David Penberthy & Will Goodings, FIVEaa, Adelaide SA, NOVA Entertainment M 3AW Breakfast; Ross Stevenson & John Burns, 3AW, Melbourne VIC, Macquarie Media Limited M 3AW Nightline/Remember When; Bruce Mansfield & Philip Brady, 3AW, Melbourne VIC, Macquarie Media Limited M The Big Sports Breakfast with Slats & TK; Michael Slater & Terry Kennedy, Sky Sports Radio, Sydney NSW, Tabcorp M Breakfast with Steve Mills & Basil Zempilas; Steve Mills & Basil Zempilas, 6PR, Perth WA, Macquarie Media Limited M Nights with Steve Price; Steve Price & Andrew Bolt, 2GB, Sydney NSW, Macquarie Media Limited M BEST ON-AIR TEAM COUNTRY & PROVINCIAL Bangers & Mash; Janeen Hosemans & Peter Harrison, 2BS Gold, Bathurst -

Chapter 3: the State of the Community Broadcasting Sector

3 The state of the community broadcasting sector 3.1 This chapter discusses the value of the community broadcasting sector to Australian media. In particular, the chapter outlines recent studies demonstrating the importance of the sector. 3.2 The chapter includes an examination of the sector’s ethos and an outline of the services provided by community broadcasters. More detail is provided on the three categories of broadcaster identified as having special needs or cultural sensitivities. 3.3 The chapter also discusses the sector’s contribution to the economy, and the importance of the community broadcasting sector as a training ground for the wider media industry including the national and commercial broadcasters. Recent studies 3.4 A considerable amount of research and survey work has been conducted to establish the significance of the community broadcasting sector is in Australia’s broader media sector. 3.5 Several comprehensive studies of the community broadcasting sector have been completed in recent years. The studies are: Culture Commitment Community – The Australian Community Radio Sector Survey Of The Community Radio Broadcasting Sector 2002-03 62 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Community Broadcast Database: Survey Of The Community Radio Sector 2003-04 Financial Period Community Radio National Listener Surveys (2004 and 2006) Community Media Matters: An Audience Study Of The Australian Community Broadcasting Sector. 3.6 Each of these studies and their findings is described below. Culture Commitment Community – The Australian Community Radio Sector1 3.7 This study was conducted between 1999 and 2001, by Susan Forde, Michael Meadows, Kerrie Foxwell from Griffith University. 3.8 CBF discussed the research: This seminal work studies the current issues, structure and value of the community radio sector from the perspective of those working within it as volunteers and staff. -

Commercial Radio

MEDIA RELEASE 8 May 2009 Melbourne first on the east coast to switch on digital radio Commercial radio stations in Melbourne MIX, GOLD, SEN, 3AW, 3MP, FOX, MAGIC, TRIPLE M, NOVA, VEGA, Sport 927, Radar, Pink Radio, Koffee and NovaNation create radio history on Monday, 11 May 2009 when they begin broadcasting the first permanent DAB+ digital radio services on the east coast of Australia. Joan Warner, chief executive officer of Commercial Radio Australia the industry body that has driven the move to digital radio said Monday was another milestone for the industry in Australia following the switch on of DAB+ digital radio in Perth last week. “The possibilities for digital radio in the sport loving state of Melbourne are very exciting. AFL final calls on radio with scrolling text scores and stats or the Melbourne Cup with photos of winners or pause and then rewind if you missed the end of the race - these are all possible with the new capabilities of digital radio,’ said Ms Warner. “DAB+ services in Melbourne have been greatly anticipated with many of the digital radio manufacturers such as Pure, Sangean, Teac, Roberts and Yamaha based in Melbourne. The digital radio switch on in Perth went very smoothly and traffic to our www.digitalradioplus.com.au website has been very high with listeners seeking more information about digital radio.” “The switch on of digital radio is a culmination of seven years work with the Federal Government, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA), commercial broadcasters, the ABC and SBS, together with retailers and manufacturers of digital radios to ensure a comprehensive and coordinated switch on of a compelling new way of listening to radio,” said Ms Warner. -

Tuning in to Community Broadcasting

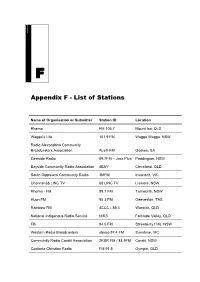

F Appendix F - List of Stations Name of Organisation or Submitter Station ID Location Rhema FM 105.7 Mount Isa, QLD Wagga’s Life 101.9 FM Wagga Wagga, NSW Radio Alexandrina Community Broadcasters Association ALeX-FM Goolwa, SA Eastside Radio 89.7FM – Jazz Plus Paddington, NSW Bayside Community Radio Association 4BAY Cleveland, QLD South Gippsland Community Radio 3MFM Inverloch, VIC Channel 68 LINC TV 68 LINC TV Lismore, NSW Rhema - FM 89.7 FM Tamworth, NSW Huon FM 95.3 FM Geeveston, TAS Rainbow FM 4CCC - 89.3 Warwick, QLD National Indigenous Radio Service NIRS Fortitude Valley, QLD FBi 94.5 FM Strawberry Hills, NSW Western Radio Broadcasters stereo 97.4 FM Sunshine, VIC Community Radio Coraki Association 2RBR FM / 88.9FM Coraki, NSW Cooloola Christian Radio FM 91.5 Gympie, QLD 180 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Orange Community Broadcasting FM 107.5 Orange, NSW 3CR - Community Radio 3CR Collingwood, VIC Radio Northern Beaches 88.7 & 90.3 FM Belrose, NSW ArtSound FM 92.7 Curtin, ACT Radio East 90.7 & 105.5 FM Lakes Entrance, VIC Great Ocean Radio -3 Way FM 103.7 Warrnambool, VIC Wyong-Gosford Progressive Community Radio PCR FM Gosford, NSW Whyalla FM Public Broadcasting Association 5YYY FM Whyalla, SA Access TV 31 TV C31 Cloverdale, WA Family Radio Limited 96.5 FM Milton BC, QLD Wagga Wagga Community Media 2AAA FM 107.1 Wagga Wagga, NSW Bay and Basin FM 92.7 Sanctuary Point, NSW 96.5 Spirit FM 96.5 FM Victor Harbour, SA NOVACAST - Hunter Community Television HCTV Carrington, NSW Upper Goulbourn Community Radio UGFM Alexandra, VIC -

Community Participation in the Development of Digital Radio: the Australian Experience

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Spurgeon, Christina, Rennie, Ellie, & Ming Fung, Yat (2011) Community participation in the development of digital radio: The Australian experience. In Lowes, N (Ed.) Record of the Communications Policy and Research Forum 2011. Network Insight Pty Ltd, Australia, pp. 166-179. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/49677/ c First published November 2011. Copyright 2011 Network Insight Pty Ltd & C. Spurgeon, E. Rennie and Y. Fung. This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.networkinsight.org/ events/ cprf2011.html This is the published version of the following conference paper: Spurgeon, Christina L., Rennie, Elinor M., & Ming Fung, Yat (2011) Community participation in the development of digital radio : the Australian experience.