P the Party 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PATTERSON, William

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 10-1-2015 PATTERSON, William MSRC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, MSRC, "PATTERSON, William" (2015). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 152. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/152 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCOPE NOTE The papers of William Lorenzo Patterson (1891-1980), often known as “Mr. Civil Rights,” document the life of the noted political activist, lawyer, orator, organizer, writer and Communist from San Francisco. The papers, which contain correspondence, printed materials, writings, and clippings, span the years 1919-1979. The bulk of the material covers the mid-1950s through 1979 when Patterson lived in New York. The collection measures approximately 15.5 linear feet and mostly highlights Patterson's political activism. His professional career as a lawyer can be analyzed through various cases he worked on through the Communist Party U.S.A. and the International Labor Defense. A view into his personal life can be obtained through his diaries and birthday tributes, as well as in the drafts and galleys of his autobiography, The Man Who Cried Genocide: An Autobiography. Correspondence with his third wife, Louise Thompson Patterson, their daughter, Mary Lou, and fellow activist leaders gives insight into some personal and political beliefs of Patterson, as do his writings on race relations, social injustices and the political activism of various individuals and organizations. -

Dobbs on Truckers Strike Rebecca Finch, New York Socialist Workers Party Candi in New York City

FEBRUARY 22, 1974 25 CENTS VOLUME 38,1NUMBER 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE On-the-scene rel}orts Minnesota truckers vote Feb. 10 to continue strike. Reporters for the Militant aHended strike meetings around the country. For their reports, and special feature on Teamsters union and independent truckers in 1930s and today, see pages 5-9. riti m1ners• ae eat In Brief BERRIGAN REFUSED JOB AT ITHACA: 300 angry prisoners labeled "special offenders." students confronted Ithaca College President Henry Phillips Delegations from Rhode Island, Maine, and Connecti Feb. 7, demanding to know why the college withdrew an cut attended the rally, which was very spirited, despite offer of a visiting professorship to Father Daniel Berrigan. a heavy snowstorm. Speakers at the rally included Richard THIS The college made the offer last December and President Shapiro, executive director of the Prisoners Rights Project; Phillips withdrew it one month later without consulting Russell Carmichael of the New England Prisoners Associa students and faculty. tion; State Representative William Owens; and Jeanne Laf WEEK'S This was the second meeting called by students since ferty, Socialist Workers Party candidate for attorney gen a petition signed by 1,000 students failed to elicit a eral of Massachusetts. MILITANT response from the administration. The students are pro testing the arbitrary decision and demanding a full ex PUERTO RICAN POETRY FESTIVAL PLANNED: The 3 Union organizers speak planation for the withdrawal of the offer. Berrigan recently Committee for Puerto Rican Decolonization, an organiza out on fight of women criticized Israel's expansionist policies in the Mideast, which tion supporting the independence of Puerto Rico, is spon workers brought slanderous charges from pro-Zionist groups that soring a festival of Puerto Rican poetry. -

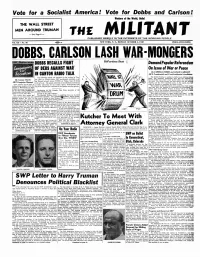

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

Verizon Strikers Stand up to Attacks on Their Unions

AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.50 · FRANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE Capitalism turns Ecuador quake into a social disaster — PAGE 8 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 80/NO. 18 MAY 9, 2016 Washington, Verizon strikers stand up ‘Workers, Moscow seek to attacks on their unions unions need to impose new Workers rally, answer bosses’ propaganda to control Mideast ‘order’ job safety’ BY MAGGIE TROWE BY JOHN STUDER Washington and Moscow are scram- “My job at Verizon has gotten more bling to hold together an agreement dangerous. I’ve been electrocuted to impose some stability and order in twice on the job, once while they Syria and the broader Mideast region. made me work by myself,” John Hop- But the competing interests of differ- ent ruling classes and factions, includ- Socialist Workers Party ing between the U.S. and Russian gov- ernments themselves, keep getting in candidates speak out the way. Millions of workers and farm- ers in the region pay a terrible price for per, a 25-year outside field technician the ongoing bloodshed. from Rockland County, New York, Talks on ending the five-year war told Socialist Workers Party presi- in Syria hit a stumbling block when dential candidate Alyson Kennedy forces opposing the regime of Presi- and campaign supporter Tony Lane as dent Bashar al-Assad declared a pause they joined a strike rally in Trenton, in their participation April 18. They New Jersey, April 25. “You put your accused the Syrian government of life on the line but the company is un- refusing to end hostilities or to allow CWA District 2-13 grateful.” Strikers and supporters picket Philadelphia Verizon store April 22. -

FEDERAL Bureveg" INVESTIGATION

✓ PO-20 (Rev. 3-1-5 9 ) • Or- FEDERAL BUREVeg" INVESTIGATION RLPORTING OFFICE OFFICE OF ORIGIN DATE INVESTIGATIVE PERIOD SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISC 12/31/63 7/11/63 - 12/16/63 ITypEoRy TITLE OF CASE RErc*TAAIDREN L. LITTLE rew FPCC - SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION CHARACTER OF CASE IS - C, CUBA, SWP; RA - CUBA 9 'REFERENCE: Report of SA WARREN L. LITTLE dated 7/11/63. _ p* .1 LEAD: . SAN FRANCISCO OFFICE A AT SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA: Will continue to follow and report the activities of the FPCC in the San Francisco Division. ADMINISTRATIVE DATA: Copies of this report are being disseminated to Los Angeles, San Diego, local intelligence agencies and INS because of their interest in this matter. CLASSIFIED BY s1 D E C F Y 25X_ qa198 SPECIAL AGENT APPROVED IN CHARGE DONOTWMTEINSPACIMSELOW CCiPIES PARDCP• - Bureau (97-4198-47) (RM) 2 - G-2, Sixth Army, San Francisco (RM)1 1 - OSI, Travis AFB, San Francisco (RM) 1 - DIO, 12th ND, San Francisco (By Hand) - INS, San Francisco ( 2 New York (97-2184) M) - Los Angeles (105-87 n o) (RM) 1 - San Diego (105-3809) (Info) (RM) 1 - San Francisco (97-347) Dissemination Record of Attached Report notations Agency Request Recd, Date Fwd. Now Pwd, B SF 97-347 VLL/rew This report is being classified confidential in order to protect the identity of the informants of continuing value used therein and whose identity, if made known, could beprejudicial to the national defense interests. The deposit of 5417.81 on 11/5/63, was reviewed by SA LITTLE and it was noted that the deposit was made up of numerous-personal checks in small amounts - apparently in response to the appeal in the 10,21/63, BAFPCC. -

Nixon's Vietnam Threat

Nixon's Vietnam threat An Editorial President Nixon's declaration that "we will not tolerate attacks which result in heavier casualties to our men at a time that we are honestly trying to seek peace at the conference table" has the sickening ring of the big-lie technique. With U.S. bombs raining down on South Vietnam to an extent never before known PAUL BOUTELLE in war; with more than half a million American men stationed in that country to carry out a genocidal war for the petty dictators in Saigon; it is clear who bears for Mayor of New York the blame for American and other casualties in that country. The administration's hypocritical outrage over the NLF response to their continuing warfare shows that now, as when Washing ton first launched its invasion, the purpose is to crush a national liberation struggle. Nixon is apparently indignant because the Vietnamese refuse to yield despite Washing ton's bombs. He also resents the fact that the NLF V ote actions help expose Washington's lying face in Paris. Nixon- like Johnson before him is using the Paris talks to lull the American people into believing that the end of the war is near and that Washington is seeking Socialist Workers peace. In reality, Washington is stepping up its aggression against South Vietnam. On Feb. 11, just three weeks before the new NLF offensive, the New York Times carried an analysis of U.S. objectives in South Vietnam, written by its chief Saigon correspondent, Charles Mohr. Mohr stated "the South Vietnamese plan to bring the number of hamlets with some security protection [read "Saigon control"] to more than 8,000 by April. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft

Workers of the World, Unite! SPECIAL SWP CONVENTION ISSUE THE MILITANT __________ PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE __________________ Vol. XII— No. 28 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, JULY 12, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS AND CARLSON ADDRESS NATION IN BROADCASTS FROM SWP CONVENTION Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft. SWP Candidates Address the Nation Inspiring Five-Day Gathering The Two Opens Presidential Campaign A m e rica s Of Socialist Workers Party By Art Preis James P. Cannon’s Key-Note Speech . NEW YORK, July 6 — Cheering to the echo the choice of Farrell Dobbs and Grace Carlson as first Over the ABC Network on July 1st Trotskyist candidates for U. S. President and Vice* President, the 13th National Convention of the So The following is the keynote speech delivered by James cialist Workers Party sum-® Cannon, National Secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, a propaganda blow been struck to the party’s 13th convention at 11:15 P. M. on July 1, and moiled the American peo in this country for the socialist broadcast over Radio network ABC at that time. ple to join with the SWP cause. That millions of people in a forward march to a Workers heard the SWP call is shown by Comrade Chairman, Delegates and Friends: and Farmers Government and the flood of letters and postcards We meet in National Convention at a t'ime of the gravest socialism. that hit the SWP National Head quarters in the first post-holiday world crisis— a crisis which contains the direct threat of a third Ih' an atmosphere charged with mail deliveries this morning. -

~ Marxism and the Negro Struggle

~ Marxism and The Negro struggle Harold Cruse George Breitman Clifton DeBerry Merit Publishers 873 Broadway New York, N. Y. 10003 First printing March, 1965 Second printing June, 1968 Printed in the United States of America ns Harold Cruse's two-part article, "Marxism and the Negro," appeared in the May and June 1964 issues of the monthly magazine Liberator and is reprinted here with its permission. A one-year subscription to Liberator costs $3 and may be ordered from Liberator, 244 East 46th Street, New York, N. Y. 10017. George Breitman's five-part series, "Marxism and the Negro Struggle," appeared during August and September 1964 in the weekly newspaper The Militant and is reprinted here with its permission. A one-year subscription to The Militant costs $3 and may be ordered from The Militant, 873 Broadway, New York, N. Y. 10003. Clifton DeBerry's article, "A Reply to Harold Cruse," is reprinted from the October 1964 issue of Liberator. Contents MARXISM AND THE NEGRO By Harold Cruse Part I 5 Part 11 11 MARXISM AND THE NEGRO STRUGGLE By George Breitman What Marxism Is and How It Develops 17 The Colonial Revolution in Today's World 23 The Role of the White Workers 29 The Need and Result of Independence 34 Relations Between White and Black Radicals 40 A REPLY TO HAROLD CRUSE By Clifton DeBerry 45 Marxism and the Negro By HAROLD CRUSE Part I When the Socialist Workers highest level of organizational Party (Trotskyist) announced in the scope and programmatic independ- New York Times, January 14, that ence in this century . -

Morris Childs Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf896nb2v4 No online items Register of the Morris Childs papers Finding aid prepared by Lora Soroka and David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1999 Register of the Morris Childs 98069 1 papers Title: Morris Childs papers Date (inclusive): 1924-1995 Collection Number: 98069 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English and Russian Physical Description: 2 manuscript boxes, 35 microfilm reels(4.3 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, reports, notes, speeches and writings, and interview transcripts relating to Federal Bureau of Investigation surveillance of the Communist Party, and the relationship between the Communist Party of the United States and the Soviet communist party and government. Includes some papers of John Barron used as research material for his book Operation Solo: The FBI's Man in the Kremlin (Washington, D.C., 1996). Hard-copy material also available on microfilm (2 reels). Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Childs, Morris, 1902-1991. Contributor: Barron, John, 1930-2005. Location of Original Materials J. Edgar Hoover Foundation (in part). Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items, computer media, and digital files. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos, films, or digital files during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all material is immediately accessible. -

Support the Socialist Alternative in 1992!

• AUSTRALIA $2.00 • BELGIUM BF60 • CANADA $2.00 • FRANCE FF1 0 • ICELAND Kr150 • NEW ZEALAND $2.50 • SWEDEN Kr1 0 • UK £1.00 • U.S. $1 .50 INSIDE Socialist candidate arrested at Peoria Caterpillar rally THE - PAGE 2 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 56/ NO. 14 April 10. 1992 Defend Support the socialist abortion alternative in 1992! rights! Tens of thousands of supporters of abor Warren and DeBates campaign against tion rights will be marching in the streets of Washington. D.C.. April 5. This demonstra tion will be an important countermobilization two parties of war, racism, depression to the unrelenting attacks by the government BY GREG McCARTAN WASHINGTON. D.C. - The Socialist EDITORIAL Workers Party candidates for U.S. president and vice-president. James Warren and Es and right-wing forces against a woman's telle DeBates, kicked off their campaign at right to choose. a national press conference here March 31. The Jan. 22, 1973, Supreme Court de The two candidates said they will join c ision legalizing abortion was a historic victory for the rights of women. Be fore supporters across the country for the next the Roe v. Wade decree abortion was ille eight months campaigning to present a so cialist alternative, raise an internationalist gal in most states. Thousands of women and working-class voice, and build the fight were made to bear children against their against the increasingly reactionary course will or forced into an illegal and danger ous back-alley abortion. of the two parties of big business - the Democrats and Republicans. -

Dobbs Appeals for AFL-CIO Aid to Negro Bus-Boycotters

Tammany Boss Rules t h e MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Ballot Ban Vol. XX - No. 42 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, OCTOBER 15, 1956 Price 10 Cents By Daniel Roberts On Oct. 5, the boss o f Tammany H all, Carmine De- Sapio, who is also the New York Secretary of State, ruled the Socialist Workers Party off the ballot. DeSapio acted through Barnett J. Nova, his E x -^ ecutive Deputy. Nova had pre SWP Candidate for Governor of sided over an administrative Michigan, in this issue.) Earlier Dobbs Appeals for AFL-CIO hearing (reported in last week’s this year, the liberal Democratic Militant) of challenges to the Administration arbitrarily ruled BWiP nominating petitions and the SWP off the Michigan ballot to similar petitions of the Social c(n a technicality. ist Labor Party. Nova upheld the •Once before, in 1946, the Dem challenges, although attorneys ocratic Party illegally knocked fo r both parties proved them to the SWP o ff the ballot in New be permeated with fraud. , York. The SWP fought its way Aid to Negro Bus-Boycotters The Socialist Workers Party back in 1948, 1950, 1952 and i$ now investigating possibilities 1964. of legal action against the high Once before, in 1952, the etate Women Farrñers Protest Gov’t Farm Policy handed decision of the New York Administration in Michigan, party chief. In fighting for the high-handedly ruled tie SWP off Tallahassee Officials democratic right of a minority the ballot. The iSWP fought back party to be represented on the there and then, too.