The Dark Night of Ecological Despair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film, Philosophy Andreligion

FILM, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION Edited by William H. U. Anderson Concordia University of Edmonton Alberta, Canada Series in Philosophy of Religion Copyright © 2022 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy of Religion Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942573 ISBN: 978-1-64889-292-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: "Rendered cinema fimstrip", iStock.com/gl0ck To all the students who have educated me throughout the years and are a constant source of inspiration. It’s like a splinter in your mind. ~ The Matrix Table of contents List of Contributors xi Acknowledgements xv Introduction xvii William H. -

Christianity and the Climate Crisis in Auteur Cinema

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 3-10-2021 "Will God Forgive Us?": Christianity and the Climate Crisis in Auteur Cinema Margaret Alice Parson Louisiana State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Parson, Margaret Alice, ""Will God Forgive Us?": Christianity and the Climate Crisis in Auteur Cinema" (2021). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5477. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5477 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “WILL GOD FORGIVE US?”: CHRISTIANITY AND THE CLIMATE CRISIS IN AUTEUR CINEMA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Margaret Alice Parson B.A., Otterbein University, 2015 M.A., Ball State University, 2017 May 2021 For Tegan ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation, as with all dissertations, is a communal act. Without the massive support of my community, it never would have come into being. Most significantly, Dr. Bryan McCann. This project was completed because of your empathy and guidance. I can never thank you enough. The other members of my committee, Drs. Mack, Saas, and Shaffer have all offered their expertise and kindness in this project’s growth, and I of course am indebted to them for their comments and encouragement. -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE -

First Reformed De Paul Schrader Charlotte Selb

Document generated on 09/24/2021 1:02 p.m. 24 images First Reformed de Paul Schrader Charlotte Selb 1968… et après ? Number 187, June 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/88713ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Selb, C. (2018). Review of [First Reformed de Paul Schrader]. 24 images, (187), 158–159. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2018 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ POINT DE VUE First Reformed de Paul Schrader PAR CHARLOTTE SELB 158 En 1976, quelques jours avant que Taxi Driver ne remporte la Palme d’Or au festival de Cannes, son jeune scénariste Paul Schrader rencontre à Paris pour une entrevue son cinéaste culte Robert Bresson, alors en attente de reprendre le tournage de Le diable probablement. Schrader a publié quatre ans plus tôt Transcendental Style in Film, un livre consacré à Ozu, Dreyer et Bresson, qu’il considère être « le plus important artiste spirituel vivant ». La conversation entre les deux auteurs, parue dans le magazine Film Comment1, aborde longuement les thèmes de la spiritualité et du suicide. -

Film Review First Reformed (Paul Schrader, US 2017)

James Lorenz Film Review First Reformed (Paul Schrader, US 2017) Most of the initial critical response to Paul Schrader’s latest film has largely ig- nored the elephant in the room: the extensive influence of Journal d’un curé de campagne (Diary of a Country Priest, Robert Bresson, FR 1951) and Natt- vardsgästerna (Winter Light, Ingmar Bergman, SE 1963) on the film. This re- view seeks to remedy this failing by analysing First Reformed through an em- phasis on its relationship with these two films. This approach functions on three levels, which this review will explore sequentially: narrative, thematic concern and form. The plot of First Reformed is best summarised by considering these two ma- jor influences. Indeed, Schrader’s pastiche of these two films is to transpose Bresson’s protagonist from Diary of a Country Priest into the scenario that challenges Bergman’s protagonist at the beginning of Winter Light: Ernst Toller (Ethan Hawke) is Schrader’s conflicted minister and, like Bresson’s priest, he suffers simultaneously from a crisis of faith and from stomach pain caused by cancer. The events of the film are set in motion when – just as in Winter Light – a young wife brings her reluctant husband to Toller for counselling. Whereas Bergman’s troubled husband despairs at the threat of nuclear war, Schrader’s husband, Michael (Philip Ettinger), is an eco-activist tormented by the threat of climate change. With prophetic urgency, he argues that it is immoral to bring a child into the world because an environmental cataclysm is imminent. Bent on this apocalyptic vision, he reveals he wants his pregnant wife, Mary (Amanda Seyfried), to abort their unborn child. -

“El Reverendo”, Conciencia Y Culpabilidad. Federico García Serrano

El puente rojo. “El reverendo”, conciencia y culpabilidad. Federico García Serrano El reverendo, conciencia y culpabilidad (First Reformed, Paul Schrader, 2017) Un ex capellán military, el reverendo Ernst Toller, expulga su sentido de culpabilidad por la muerte de su hijo en la Guerra de Irak prestando servicios religiosos en la pequeña parroquia de Snowbridge, cerca de Nueva York, en las fechas en que se va a celebrar el 250 aniversario de su construcción. Buscando su ayuda espiritual acude a él la joven Mary, embarazada, que lucha por sacar de la depresión a su marido, Michael, un activista del ecologismo que no desea traer un hijo a un mundo degradado y en descomposición. Con el encuentro entre ambos hombres, dos mentes atribuladas por sus conciencias y su sentido de la culpabilidad entran en conexión, desencadenando una búsqueda intelectual que el reverendo Toller va escribiendo en su diario, una crónica que misteriosamente nace con una fecha explícita de caducidad. El planteamiento del film parte de la de culpa y la necesidad de encontrar la soledad espiritual de un hombre esperanza a través de la vida espiritual abrumado por sus problemas de despierta dentro de él una necesidad de conciencia que afronta el reto de búsqueda que, lejos de hacerle avanzar superarlos a través de la fe y de la hacia una salida, va ahondando en su entrega al servicio de sus feligreses. El desesperación, con un panorama que se encuentro con alguien que sirve para va viendo abocado a la autodestrucción, confrontar y exteriorizar sentimientos tanto del cuerpo como de la mente. -

New Brunswick. Torrors of Dyspepsia

TIMES. NEW BRUNSWICK, N. J.: MONDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 19, 1872. PRICE THREE CENTS. er style very much," remarked So- RAILROAD TRAVEL. QNE MILLION OF LIVES SAVED! BUSINESS CA.iut. MISCELLANEOUS. THE DAILY TIMES. hia. If AVant a His one of the remarkable facts of this re- Pennsylvania Railroad — Sew markable age. Dot merely that BO many per- ABRICiHT THOUGHT. " Well, I don't agree with every- York Division sons are the victims of dyspepsia or indigestion, hing he says to me," was Kitty's ut its willing victims. Now, we would not be Beautiful Girls " What is the matter with you, mergetic answer. " And I have no I Auctione e r, nderstood to say that any one regards HOLIDAY PRESENT Ijspepsia with favor, or feuls disposed to rank Kitty?" asked Sophia Williamson,as ntention of conforming my taste and t among the luxuries of life. Far from it deas to his." 55 Albany Street, - WITH BEAUTIFUL CURLS. "hose who have experienced its torments her sister entered the room. Kitty GO TO ou'd scout such an idea. All dread it, and threw herselt on the lounge, a cross " Not while he devotes two-thirds N.EW r.-;uNS'A"i<:K. N. :.. ould gladly dispense with its unpleasant expression clouding her lace. if his time to Florence iTaynes," said attend sale* m c.tv or country. atniliarities. Mark Tapley, who was jolly WINTER ARRA\GEJIE\TS nder all the trying circumstances in which " I am not going to Sarah Willett's sabelle, a little spitelullyr e was plac d, never had an attack of dys- party in one of my old dresses. -

Download 2018 Festival Program

PHOTO COURTESY OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES/PHOTOFEST DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944), THE Inaugural Dr. Saul and Dorothy Kit DIRECTED BY BILLY WILDER. SHOWN FROM LEFT: BARBARA Film Noir Festival STANWYCK, FRED MACMURRAY THE STUFF THAT DREAMS ARE MADE OF Paris 1946 and american film Noir Lenfest Center for the Arts 615 West 129th Street, between Broadway and 12th Avenue arts.columbia.edu lenfest.arts.columbia.edu Dr. Saul and Dorothy Kit Film Noir Festival MARCH 21–25, 2018 Festival Introduction “It was during the summer of 1946 that the French public experienced the revelation of a new kind of American film.” Thus begins Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton’s Panorama du film noir amèricain (1955), the first book ever written about a type of film that, in America, still had no name: film noir. This festival—the first in a ten-year series devoted to noir’s legacy—returns us to that moment of revelation just over 70 years ago. The inaugural Dr. Saul and Dorothy Kit Film Noir Festival presents eight films that screened in Paris that season and inspired the label “film noir.” The story of that christening is familiar to film history. With the war over and a backlog of wartime Hollywood films playing in Parisian movie theaters, French audiences immediately perceived a break from the style and genres of 1930s American cinema. In an August 1946 essay “Un nouveau genre ‘policier’: L’aventure criminelle,” critic Nino Frank spoke of a new generation of filmmakers, led by John Huston and Billy Wilder, who rejected the humanism of directors like John Ford and Frank Capra to explore “criminal psychology” and the “dynamism of violent death” in films like The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Double Indemnity (1944). -

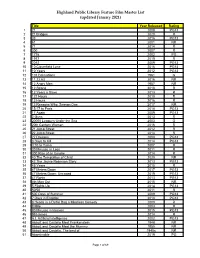

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (Updated January 2021)

Highland Public Library Feature Film Master List (updated January 2021) Title Year Released Rating 1 21 2008 PG13 2 21 Bridges 2020 R 3 33 2016 PG13 4 61 2001 NR 5 71 2014 R 6 300 2007 R 7 1776 2002 PG 8 1917 2019 R 9 2012 2009 PG13 10 10 Cloverfield Lane 2016 PG13 11 10 Years 2012 PG13 12 101 Dalmatians 1961 G 13 11.22.63 2016 NR 14 12 Angry Men 1957 NR 15 12 Strong 2018 R 16 12 Years a Slave 2013 R 17 127 Hours 2010 R 18 13 Hours 2016 R 19 13 Reasons Why: Season One 2017 NR 20 15:17 to Paris 2018 PG13 21 17 Again 2009 PG13 22 2 Guns 2013 R 23 20000 Leagues Under the Sea 2003 G 24 20th Century Women 2016 R 25 21 Jump Street 2012 R 26 22 Jump Street 2014 R 27 27 Dresses 2008 PG13 28 3 Days to Kill 2014 PG13 29 3:10 to Yuma 2007 R 30 30 Minutes or Less 2011 R 31 300 Rise of an Empire 2014 R 32 40 The Temptation of Christ 2020 NR 33 42 The Jackie Robinson Story 2013 PG13 34 45 Years 2015 R 35 47 Meters Down 2017 PG13 36 47 Meters Down: Uncaged 2019 PG13 37 47 Ronin 2013 PG13 38 4th Man Out 2015 NR 39 5 Flights Up 2014 PG13 40 50/50 2011 R 41 500 Days of Summer 2009 PG13 42 7 Days in Entebbe 2018 PG13 43 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag a Mindless Comedy 2000 R 44 8 Mile 2003 R 45 90 Minutes in Heaven 2015 PG13 46 99 Homes 2014 R 47 A.I. -

History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ "The Town Clock Church" History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ

"The Town Clock Church" History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ "The Town Clock Church" History of the First Reformed Church New Brunswick, NJ by the Rev. Dr. J David Muyskens published by the Consistory 1991 FOREWORD The last time someone compiled a history of First Reformed Church was when Dr. Richard H. Steele presented his Historical Discourse Delivered at the Celebration of the One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the First Reformed Dutch Church, New Brunswick, N.J. That was on October 1, 1867. The discourse was published by the Consistory. There are still a few copies in existence of that volume. But it seems time for an update. My work on writing the history of First Church began with a series of Wednesday evening lectures during lent some years ago. My research continued since then as I read consistory minutes, old newsletters, and talked to some of the older members of the congregation compiling the story that follows on these pages. It is a story in which the hand of God is evident. It is the story of dedicated people who gave much in the service of Christ. It is the story of a church which has played a central role in the life of its community. For a time it was known as ''the Town Clock Church' as its tower has housed the town clock of the city of New Brunswick for one hundred and sixty years. Its earliest names reflected the fact that it was a church organized to serve its community. The names expressed the geographic location of its congregation. -

First Reformed

first reformed In FIRST REFORMED volgen we een dominee die aangedaan?’, vraagt Michael hem tijdens hun zich na de dood van zijn zoon staande probeert eerste gesprek. Het is een vraag die Toller te houden binnen een kleine Nederlands- tijdens de gehele film zal achtervolgen. Hervormde kerkgemeenschap. Zijn Het is interessant om te zien hoe regisseur Paul wankelende relatie met God wordt vervolgens Schrader (CAT PEOPLE, maar ook de schrijvende nóg verder op de proef gesteld. man achter klassiekers als TAXI DRIVER en RAGING BULL) een politiek beladen onderwerp Dominee Toller (meeslepende rol van Ethan als klimaatverandering in religieus licht zet. Hawke) wordt op een kwade dag om hulp FIRST REFORMED wil laten zien dat het klimaat gevraagd door de zwangere Mary. Haar man wél degelijk een onderwerp is waar de kerk zijn Michael, een radicale milieuactivist die ervan verantwoordelijkheid voor moet nemen, als overtuigd is dat de wereld niet meer te redden onderdeel van goed rentmeesterschap. De film valt, blijkt depressief. De alarmbellen gingen bij doet dit via kraakheldere cinematografie en een Mary rinkelen toen ze een bomgordel in hun fascinerend, multidimensionaal garage vond en nu wil ze dat Toller ervoor zorgt hoofdpersonage dat het verhaal bijna in zijn dat Michael weer de oude wordt. Dat blijkt nog eentje lijkt te dragen. knap lastig te zijn. De dominee heeft het namelijk al moeilijk regie: Paul Schrader genoeg met zichzelf: hij vecht al een tijd met met: Amanda Seyfried, Ethan Hawke, Cedric the zijn geloof doordat hij zijn zoon heeft verloren. Entertainer En ergens vindt hij dat Michael in zijn kritiek op USA 2018 • drama, thriller • 113 min. -

Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (2Nd Edition)

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 24 Issue 1 April 2020 Article 52 March 2020 Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (2nd edition) Michael Gibson Vanderbilt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Part of the Religion Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Gibson, Michael (2020) "Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (2nd edition)," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 24 : Iss. 1 , Article 52. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol24/iss1/52 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (2nd edition) Abstract This is a book review of Paul Schrader's Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, 2nd edition (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018). Keywords film, cinema, eligion,r mysticism, aesthetics, Paul Schrader, Martin Scorsese, Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, Stanley Kubrick, slow cinema Author Notes Michael Gibson is a senior acquisitions editor at Lexington Books, the academic imprint of Rowman & Littlefield, and contributing editor in film for The Bias magazine. He is a PhD candidate at anderbiltV University and author of a forthcoming monograph on film director Stanley Kubrick (Rutgers University Press). This book review is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol24/iss1/52 Gibson: Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (2nd edition) Schrader, Paul, Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer.