Vietnamese Christians Sharing God's Beauty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's Theses UARC.0666

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8833tht No online items Finding Aid for the University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses UARC.0666 Finding aid prepared by University Archives staff, 1998 June; revised by Katharine A. Lawrie; 2013 October. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 August 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections UARC.0666 1 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses Creator: University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Identifier/Call Number: UARC.0666 Physical Description: 30 Linear Feet(30 cartons) Date (inclusive): 1958-1994 Abstract: Record Series 666 contains Master's theses generated within the UCLA Dance Department between 1958 and 1988. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Copyright of portions of this collection has been assigned to The Regents of the University of California. The UCLA University Archives can grant permission to publish for materials to which it holds the copyright. All requests for permission to publish or quote must be submitted in writing to the UCLA University Archivist. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], University of California, Los Angeles. Department of Dance Master's theses (University Archives Record Series 666). UCLA Library Special Collections, University Archives, University of California, Los Angeles. -

The Role of Dance in Haitian Vodou Dancing, Along with Singing And

The Role of Dance in Haitian Vodou Camille Chambers, University of Florida Dancing, along with singing and drumming, is a fundamental part of Haitian Vodou ritual ceremonies. Just as how the songs and the drums have a spiritual function and reflect a creolized heritage, dance holds a similar value in Vodou. As a religion that is kinesthetic in nature, dance is part of the physical manifestation of serving the lwa. Dance is not only an important part of Haitian Vodou but also of Haitian culture, in which there are two types of dance: secular and sacred (Dunham 1947: 15). For the purpose of this paper, the sacred dance will be addressed. Many anthropologists have studied ritual dances in the African diaspora of the Caribbean. Through the studies of dance in Haitian Vodou, the connection to spirituality and memory provided to the community through dance and music in Vodou ceremonies is evident. The community is a key element in Vodou ceremonies. Hebblethwaite argues that Vodou songs are important because they are the “living memory of a Vodou community” (2012: 2). Dance holds the same importance in preserving this “living memory.” Vodou songs educate about the lwa and the philosophy of Vodou and they signal the transitions between phases of the ceremony. Dance in Vodou also educates about the lwa and philosophy and through careful study of the different dances, one may also understand how dances change in the different phases of the ceremony. Before getting into the study of dances, the importance of drums must be addressed. Wilcken (2005) describes the drums as providing the fuel and guidance to the dance participants. -

Katherine Mansfield Gurdjieff's Sacred Dance

Katherine Mansfield and Gurdjieff’s Sacred Dance James Moore First published in Katherine Mansfield: In From the Margin edited by Roger Robinson Louisiana State University Press, 1994 The facts are singular enough: Katherine Mansfield, a young woman who could scarcely walk or breathe, absorbed in sacred dances that lie on the very cusp of human possibility. Some ideal of inner conciliation—neighbourly to the dancers’ purpose there— seems to have visited Katherine almost precociously. At twenty, she had written, “To weave the intricate tapestry of one’s own life, it is well to take a thread from many harmonious skeins—and to realise that there must be harmony.” i The tapestry she had achieved in the ensuing years had been a brave one: on a warp of suffering she had imposed a woof of literary success. Slowly, implacably, her body but not her spirit of search had failed her, and in her final extremity she arrived at a resolution: “Risk! Risk anything!” 2 So determined, she entered the gates of the Château du Preiuré, at Fontainbleau-Avon, on Tuesday, October 17, 1922, and there, at George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, she lived out her last, intense three months. There, on January 9, 1923, she died. Katherine Mansfield and Gurdjieff’s Sacred Dance. Copyright © James Moore 1994, 2006. 1 www.Gurdjieff-Biblography.com No one imagines that Mansfield’s fundamental significance lies outside her oeuvre, her individuality, and her life’s full spectrum of personal relationships; no one would claim some mystical apotheosis at Fontainebleau that overrode all that. -

Nordic Roots Dance Kari Tauring - 2014 "Dance Is a Feature of Every Significant Occasion and Event Crucial to Tribal Existence As Part of Ritual

Nordic Roots Dance Kari Tauring - 2014 "Dance is a feature of every significant occasion and event crucial to tribal existence as part of ritual. The first thing to emphasize is that early dance exists as a ritual element. It does not stand alone as a separate activity or profession." Joan Cass, Dancing Through History, 1993 In 1989, I began to study runes, the ancient Germanic/Nordic alphabet system. I noticed that many rune symbols in the 24 Elder Futhark (100 ACE) letters can be made with one body alone or one body and a staff and some require two persons to create. I played with the combination of these things within the context of Martial Arts. In the Younger futhark (later Iron Age), these runes were either eliminated or changed to allow one body to create 16 as a full alphabet. In 2008 I was introduced to Hafskjold Stav (Norwegian Family Tradition), a Martial Arts based on these 16 Younger Futhark shapes, sounds and meanings. In 2006 I began to study Scandinavian dance whose concepts of stav, svikt, tyngde and kraft underpinned my work with rune in Martial Arts. In 2011/2012 I undertook a study with the aid of a Legacy and Heritage grant to find out how runes are created with the body/bodies in Norwegian folk dances along with Telemark tradition bearer, Carol Sersland. Through this collaboration I realized that some runes require a "birds eye view" of a group of dances to see how they express themselves. In my personal quest to find the most ancient dances within my Norwegian heritage, I made a visit to the RFF Center (Rådet for folkemusikk og folkedans) at the University in Trondheim (2011) meeting with head of the dance department Egil Bakka and Siri Mæland, and professional dancer and choreographer, Mads Bøhle. -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Spring 2011 VOLUME 53 NUMBER 2 Dancing the Jsacred, Moving the World

SACRED DANCE GUILD OURNAL spRING 2011 VOLUME 53 NUMBER 2 Dancing the JSacred, Moving the World For our Sacred Dance Guild’s 50th Anniversary in 2008, Emmalyn Moreno, a SDG Lifetime Member from San Luis Rey, California, wrote, choreographed and recorded our 50th Anniversary Festival Song, “MOVING MYSTERIES.” Going on three years later, our SDG Board of Directors is happy to announce that “Moving Mysteries” is now SDG’s official song/dance or Body Prayer. People of the East, People of the West Come dance in the rising of the sun. People of the North, People of the South Moving Mysteries we are one… Emmalyn is a performing artist, pianist, composer, singer, dancer and teacher who celebrates her God-given talents in her Music and Dance Ministries. She has served both on the Board of SDG and as Faculty at our Festivals. “Moving Mysteries” is recorded on her “Sister Moon” release available on her website http://musicbyemmalyn.com. You can watch a few minutes of “Moving Mysteries” being danced at our 50th Anniversary Festival by going to Moving Mysteries Festi- val 2008, and clicking on the video on our SDG website. Keep exploring our website at www.sacreddanceguild.org. You will find a “Moving Mysteries” web page with stories, pictures, and suggestions for integrat- ing “Moving Mysteries” into your work, play projects and prayers. Emmalyn Moreno, a SDG Lifetime Member from San Luis Rey, California. Encore Dance Ensemble & Luther Conant School Students dancing “Moving Mysteries” at International Dance Day 2010 Performance in Acton, Massachusetts. -

Dancing in Body and Spirit: Dance and Sacred Performance In

DANCING IN BODY AND SPIRIT: DANCE AND SACRED PERFORMANCE IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY BEGUINE TEXTS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Jessica Van Oort May, 2009 ii DEDICATION To my mother, Valerie Van Oort (1951-2007), who played the flute in church while I danced as a child. I know that she still sees me dance, and I am sure that she is proud. iii ABSTRACT Dancing in Body and Spirit: Dance and Sacred Performance in Thirteenth-Century Beguine Texts Candidate’s Name: Jessica Van Oort Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Joellen Meglin This study examines dance and dance-like sacred performance in four texts by or about the thirteenth-century beguines Elisabeth of Spalbeek, Hadewijch, Mechthild of Magdeburg, and Agnes Blannbekin. These women wrote about dance as a visionary experience of the joys of heaven or the relationship between God and the soul, and they also created physical performances of faith that, while not called dance by medieval authors, seem remarkably dance- like to a modern eye. The existence of these dance-like sacred performances calls into question the commonly-held belief that most medieval Christians denied their bodies in favor of their souls and considered dancing sinful. In contrast to official church prohibitions of dance I present an alternative viewpoint, that of religious Christian women who physically performed their faith. The research questions this study addresses include the following: what meanings did the concept of dance have for medieval Christians; how did both actual physical dances and the concept of dance relate to sacred performance; and which aspects of certain medieval dances and performances made them sacred to those who performed and those who observed? In a historical interplay of text and context, I thematically analyze four beguine texts and situate them within the larger tapestry of medieval dance and sacred performance. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 228 SP 030 589 AUTHOR Beal, Rayma

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 299 228 SP 030 589 AUTHOR Beal, Rayma K., id.; Berryman-Miller, Sherrill, Ed TITLE Dance for the Ulder Adult. Focus on Dance XI. INSTITUTION American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, Reston, VA. National Dance Association. REPORT NO ISBN-0-88314-385-2 PUB DATE 88 NOTE 176p.; Photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM AAHPERD Publications, P.O. Box 704, 44 Industrial Park Center, Waldorf, MD 20601 ($12.95 plus postage and handling). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) -- Guides General (050) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not AvailabLe from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Curriculum Development; *Dance; *Educational Resources; *Older Adults; Physical Fitness; *Program Development; Research ABSTRACT This monograph is a collection of articles designed to expand the information network, identify current programs, and provide research in the field of dance/movement and gerontology. Different approaches, techniques, and philosophies are documented by indi.fiduals who are active in the field. Articles are organized into six sections: (1) guidelines for activities with older adults; (2) programodelF; (3) research; (4) curricular program models; (5) intergenerational dance; and (6) resources. References accompany each article. The sixth section on selected reasons for dance and the older adult identifies: (1) books; (2) special publications; (3) selected articles from periodicals; (4) papers, monographs, proceedings and unpublished manuscripts; (5) masters and doctors degree theses; (6) films, videotapes, slides; (7) records, audiocassettes, manuals; (8) program and resource persons; (9) periodicals; and (10) agencies and organizations. (JD) *************mx*********x********************************vcx************ * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

Residency Packet V.3 Pages

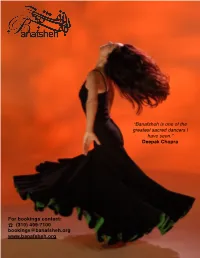

“Banafsheh is one of the greatest sacred dancers I have seen.” Deepak Chopra For bookings contact: ☎ (310) 499-7100 [email protected] www.banafsheh.org Banafsheh Internationally acclaimed Persian dance artist and educator, Banafsheh has been performing and teaching throughout North America, Europe, Turkey and Australia for a decade. In addition to contemporary Middle Eastern dance technique, Banafsheh teaches self-empowerment through dance, the inner dimensions of movement and experiential anatomy. Recognized for her fusion of high-level dance technique with spirituality, Banafsheh’s electrifying and wholly original dance style embodies the sensuous ecstasy of Persian Dance with the austere rigor of Sufi whirling – and includes elements of Flamenco, Tai Chi, and the Gurdjieff sacred Movements. Rumi lives through Banafsheh! Her movement is comprised in part by the Persian alphabet she has translated into gestures, which when put together she dances out poetic stanzas mostly from Rumi. With an MFA in Dance from UCLA and MA in Chinese Medicine, Banafsheh combines her dance expertise with the Taoist view of the internal functioning of the body, the Chakra system, Western Anatomy and Sufism to uncover movement that is at once healing, self-illuminating and connected to Spirit. The certification program she has founded, called Dance of Oneness® is about conscious embodiment. Known for her original movement vocabulary as well as high artistic and educational standards, Banafsheh comes from a long lineage of pioneering performing artists. Her father, the legendary Iranian filmmaker and actor, Parviz Sayyad is the most famous Iranian of his time. Banafsheh is one of the few bearers of authentic Persian dance in the world which is banned in her native country of Iran, and an innovator of Sufi dance previously only performed by men. -

An Investigation Into Circle Dance As a Medium to Promote Occupational Well-Being Ana Lucia Borges Da Costa

AN INVESTIGATION INTO CIRCLE DANCE AS A MEDIUM TO PROMOTE OCCUPATIONAL WELL-BEING ANA LUCIA BORGES DA COSTA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Bolton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 Table of Contents Table of figures .............................................................................................. 7 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................... 9 Dedication ...................................................................................................... 10 PhD Thesis Abstract ................................................................................... 11 Prologue ......................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................... 15 1.1 Contextualising circle dance ......................................................16 1.2 Motivation for conducting the investigation ..........................19 1.3 The rationale for the investigation ............................................19 1.4 Research questions .......................................................................22 1.5 Structure of the thesis ..................................................................23 Chapter 2 Occupational therapy, circle dance and well- being .... 26 2.1 The conceptual foundation of occupational therapy ..............27 1.1.1 Defining occupational therapy -

University of Movement Giving the Body Credit on Today’S Campuses

MOVEMENT MENU: Fresh Events at MovingArtsNetwork.com CONSCIOUS #6 SPRING 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER Soul Motion Inner-Activating with Vinn Martí Shiva Rea, UCLA graduate, transforms the learning curve. University of Movement GIVIng THE BODY CREDIT ON TODAY’S CAMPUSES PLUS AQua MantRA Lyric of Laban DIVING Into DIGItaL Decoding the DNA of Dance UPLIFTING TRendS 10 Shiva Rea shapes a perfect Natarajasana at the Devi Temple in Chidambaram, India. 16 14 5 MENTOR Lyric of Laban Rudolf Laban created a system for mapping movement that is still in use today. Ahead of FEATURES his time in the early 20th century, he created a poetic language of science and motion. 7 WARMUPS 10 Minister of Soul • Recession-proof Trendspotting Departments Diving into the mystery of the present moment • Let Your Moves Be Your Music with Vinn Martí. Editor Mark Metz shares a day of • Debbie Rosas: The Body’s Business movement with the founder of Soul Motion. • Disco Revival Saves Lives 20 VITALITY Drink Up! 14 Laura Cirolia follows her intuition to discover Dance, Dance, Education natural truths about the water we drink and why The convergence of mind and body is good news proper hydration is so important. IN D in the world of academia. 23 SOUNDS Diving into Digital ON PU R 14 In higher education, the buzzword is embodiment. Eric Monkhouse demystifies the digital options facing DJs today and provides helpful tips for EWIJK / New curricula embrace the body at interdisciplinary D O L institutions around the country. performing live with a laptop. -

The Evolution of Sacred Dance in the Judeo-Christian Tradition

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Religion 1967 The Evolution of Sacred Dance in the Judeo-Christian Tradition Jade Luerssen '67 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/religion_honproj Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Luerssen '67, Jade, "The Evolution of Sacred Dance in the Judeo-Christian Tradition" (1967). Honors Projects. 20. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/religion_honproj/20 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. THE EVOLUTION OF SACRED DANCE / IN THE JUDEO-CHRISTIAN TRADITION BY JADE LUERSSEN /} Submitted for Honors Work In the Department of Religion-Philosophy Illinois \vesleyan University Bloomington, Illinois I,,"......I.1no, i \", - S '8Sic:;:'an U�iv. Libraries Bloom1n�t�n T1l �'N�� Accepted by then Department of Religion- Philosophy of Illinois Wesleyan University in fulfillment of the requirement for departmental honors. / ��� £,{j)g� Pro ject Advisor Illinois Wesleyan Unlv. Libraries Bloominut.on Tll �1?A' TABLE OF CONTENTS I.