Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5131

Meem Library St. John's Colleae the grout St. John’s College’s Literary and Arts Magazine fall 2011 table of contents Page Title, Author 5 Shut Eye, Akiva Katz Photo by Ben Holme 6 Artwork by Isla Prieto 7 Mom, Zachary Hooper Photo by Andrew Peters 8 Untitled, Olivia Broustra 9 Photo by Rebecca Ahrens 10 Space Trip, Cheryl Abhold Photo by Haley Tethal 11 Untitled, Rhys Conger 12 Sand Dollar, Jillian Burgle 13 Grape Vine, Padraic O’Neill Photo by Audra Zook 14 The Storm, Charles Brogan 15 Photo by Rebecca Ahrens 16 Get Your Head Out of the Clouds, Arthur Lopez Photo by Rhys Conger 18 Metalhead Lament #27, Cheryl Abhold 19 Photo by Rebecca Ahrens 20 Photo by Mary Creighton 21 Passion Poem, Bryce Gorkins 22 The Self is an Empty Heart, Rhys Conger Alley Dog, Jillian Burgle 23 Photo by Andrew Peters 24 Girl Gone Wild, Sabina Rai Photo by Mary Creighton 25 Photo by Rhys Conger 26 Mercado San Telmo, Andrew Peters 27 Photo by Mary Creighton 29 Artwork by Isla Prieto 30 Photo by Rebecca Ahrens 2 table of contents Page Title, Author 31 Photo by Rebecca Ahrens 32 Psalm 51:3, Bryce Gorkins 33 Photo by Ben Holme 34 We Go Light Fires, Jillian Burgie 35 Artwork by Anastasia Kilani 36 Photo by Haley Tethal 38 Untitled, Padraic O’Neill 39 Photo by Mary Creighton 40 Photo by Andrew Peters 41 There is No Unturned Stone, Peter Horton 43 Photo by Rebecca Ahrens 44 Ode to the Interstate, Andrew Peters 45 Jared is an Elephant, John McAlmon 46 Photo by Rhys Conger 47 Excerpt from “The Ivory Tower,” Kurt Strom 48 Photo by Audra Zook 51 Photo by Mary Creighton -

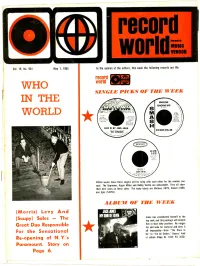

In the Opinion of the Editors, This Week the Following Records Arethe

record Formerly MUSIC VENDOR Vol. 19, No. 934 May 1, 1965 In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records arethe record WHO world //4 SINGLE PICKS OF THEWEEK IN THE !OPP' ENGINE Alamo n.,1,1)- ENGINE #9 5.1983 M Y61.33502 14.1075 1,66 WORLD Pred666dby 0 1965 Pu61,1.66 1161166d L Dove, JOBE TE 1061 C6..166. 1.50 A (BMI) 2,16 DM HLY.121205 45 REM Produced by SIX M.4737 hem .14my Kennel Mimm 6, .901111 NITS It 559 1011111915" BACK IN MY ARMS AGAIN 0, THE ,q EPIC',NA I /7 -4.'0W// I M 45 RPM 5-9791 JZSP 110415 196b,F660,6, (Bmn TIME: 2:24 L.Etc4-L -1°T,Y1ITI .44 ."C.:r11':,' Mo 7:;;,+, Within weeks these three singles will be vying with each other for thenumber one spot. The Supremes, Roger Miller and Bobby Vinton are unbeatable.They all show their best sides on these sides.The lucky labels are Motown (1015), Smash (1983) and Epic (5-9191). ALBUM OF THE WEEK (Morris) Levy And Jones has established himself in the (Soupy) Sales - The top rank, and this package will cement him in that lofty position.He ranges Great Duo Responsible far and wide for material and does it allimpeccably-from "The RaceIs For the Sensational On" to "I'm All Smiles." Buyers' kind Re -opening of N. Y.'s of album (Kapp KL 1433; KS 3433). Paramount. Story on Page 6. Paramount Show aRiot KHJ's 93 -Hour Cole Check BY DAVE FINKLE Disk Battle On and asso- NEW YORK-They alllaughed when Morris Levy HOLLYWOOD - KHJ radio ciates in his Phase Productionsannounced they were inaugu-has scheduled93consecutive rating their revived Paramountvaudeville -cum -movie showcasehoursofprogramming from first day of Pass- 29to 1 p.m. -

NOTZ EDFS PRIE Is Provided for Humanities Courses. Stunts

DOCUMENT BESUM 1. ED 211 442 ..10 C13 E45 / ! . AN ' AUTHOR Levine,, iPby H. TITLE Jumlistreet Humanities Project Learning Package. Curriculum Materials fcr Secondary Schtel Teachers and Students in Language Arts, faster)/ and Himavities. 'INSTITUTION National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH) , Washington, D.C\ Elementary and 6eccndary Program- i PUB DATE 81 NOTZ 215p. P EDFS PRIE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Black AchieveMent; Elack History; Blacks;,31cBlack Studies; Ethnic Studies; *Humanities Instruction; *Interdisciplinary 'Approach; *Language Arts; Musit Appreciation; *Music Eduation; Musicians; Secondary Education; *United States History; Units cf Study `ABSTRACI These language arts, U.S. history, and humanitges lessons for .secondary school student's are designed tc he used with "From Jumpstreet,A Stcry of Black Music," a series of13 half-hour terevIsiorli prOgrams. The'colorfgl-and rhythmic serifs explores the black muscal heritage from its African roots to its wide influence in.mcder/f American music. Each program of the series features ' performatmes end discussicn by talented contemporary entertainers, plusafilm clips and still photo sequences of Campus clack performers of,the past. This publication is divided into thr section's: language areit, history, and tht humanities. Each section beginswith a scope and sequence .outline. Examples oflesson activities fellow. point of view of . In the language arts lessons, students identify the the lyricist in selected songs by blacks,'participatein debate, give speeches, view and write a brief suinmary of the key ccnceptsin e. alven-teleyision program, and.create a dramatic scene based eke song lyric. The history lesso1s invelve'itudents in identifying characteristics of West African culture reflected in the music of black people; examining slavery, analyzing the music elpest-Civil War America, and comparing the Tanner in whichmusical etyles reflect social and political forces.A multicultural unit on dance and, poetry is provided for humanities courses. -

America the Beautiful and Other Poems from Gretna Green to Land's End

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 22^.|^to Darvarfc Colleae library FROM Afli#* (r*Z*oJ&li^eA*>U* t ni*. t »*. !/>--- 1.4. // i- •--('. -.0 .. .••-„,• -. ..- - Darvaro College library FROM £•--•*.«*#->-• 0 c-.it /V<. /.-> ... AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL AND OTHER POEMS FROM GRETNA GREEN TO LAND'S END A READING JOURNEY THROUGH ENGLAND By KATHARINE LEE BATES HI unrated Nel, $3.00 ROMANTIC LEGENDS OF SPAIN Bv GUSTAVO A. BECQUER Translated by Cornelia Frances Bates and Katharine Lee Bates llluitrated Net, f/.jo THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO. NEW YORK AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL AND OTHER POEMS BY KATHARINE LEE BATES NEW YORK THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY PUBLISHERS Copyright, 1911, By THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY. Published September, 1911. I 00 TO MARION PELTON GUILD 00 Thanks for permission to include in this volume poems already printed are rendered to the following periodicals! The Atlantic, Canadian Magazine, The Century, The Chautauquan, Christian Endeavor World, The Congrega- tionalist, The Cosmopolitan, The Critic, Everybody's Magazine, Oood Housekeeping, The Independent, Lip- pincott's Magazine, New England Magazine, The Out look, National Magazine, The Youth's Companion. The courtesy of the Chicago Madrigal Club is recog nized, too, and that of the Macmilian Publishing Com pany. CONTENTS I PAGE America the Beautiful 3 * Year of the Vision 4 Land of Hope 5 The Flag 8 The Peace-Maker 8 The Sea-Path 9 The First Voyage of John Cabot 14 Hudson's Third Voyage 14 Niagara 17" The Song of Niagara 17*" The American Coast 19 Memorial Day 20 Above the Battle . -

Winter Theme Book Winter Theme

The Winter Theme Book Winter Theme Compiled Internet Sources By Judy Santos Judy’s Kids Family Daycare Page 1 of 213 The Winter Theme Book Contents: Activities and Games Songs, Poems and Fingerplays Books Websites Fact File Holidays Page 2 of 213 The Winter Theme Book Activities And Games Page 3 of 213 The Winter Theme Book Activity and Games Index Snowflakes Three Dimensional Snowman Frosty Winter scene Whipped Soap Snowman Snowman Craft Ideas Toothpick Snowflakes Snow Idea Snowmen Snow Scenes Jello in the Snow Catch Some Snowflakes Keep Some Snowflakes Make a Snow Gauge Make a Glacier Snow Scene in a Jar Bird Treats Borax Crystal Snowflake Sparkle Snow Paint Three Dimensional Snowmen Ice Painting A "Self-sticking" Snowflake Cereal Snowflakes Snow Scenes Circle Snowmen Snowflakes Shaving Cream Snow Science Animal Tracks Snow Bubbles Thermometer Snow angels Snow Colors Freeze Edible Snowmen Edible Glacier Snow "Slush Cones" Snow "Ice-cream" Popcorn Snowmen Winter Wonderland Make a rain/snow gauge. E-Z Building with Sugar Lumps! Parent Involvement: Home Activities Fishing For Ice Cubes Page 4 of 213 The Winter Theme Book Florida Winter Snow Day! Snow: Good For All On Earth Art Activity: Puff Paint Snow Winter In January Mini Winter Books Snow Flakes Snowflake Snacks Valentine Tips Counting Activity: "Snow Peanuts" Extension To Snow Peanuts Preschool Winter Tips Snowball Soap Cooking Popcorn Snowmen Cool Cooking: Snow Ice Cream Science Activity: A Melting Snowman Science: Melting Experiment #1 Science: Melting Experiment #2 Art Activity: -

Bound for Sacramento; Travel-Pictures of a Returned Wanderer, Translated from the German by Ruth Frey Axe, Introduction by Henry R

Bound for Sacramento; travel-pictures of a returned wanderer, translated from the German by Ruth Frey Axe, introduction by Henry R. Wagner Bound for Sacramento Carl Meyer Bound for Sacramento Travel-Pictures of a returned wanderer translated from the German by Ruth Frey Axe Introduction by Henry R. Wagner Saunders Studio Press Claremont, California 1938 COPYRIGHT 1938 BY THE SAUNDERS STUDIO PRESS PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA This first edition is limited to 450 copies Bound for Sacramento; travel-pictures of a returned wanderer, translated from the German by Ruth Frey Axe, introduction by Henry R. Wagner http://www.loc.gov/resource/calbk.083 which this is copy Number 75 The Saunders Studio Press wishes to thank Mr. Phil Townsend Hanna, who has so graciously given his permission to reprint the three chapters of this translation that appeared in Touring Topics, in the June, July, and October numbers of 1932, in order to make available the entire text; Mr. Henry R. Wagner for calling our attention to its merits and for his fine introduction and finally, the Huntington Library for permission to use photostats of the original in its collection. LINDLEY BYNUM, editor. VII Table of Contents Introduction IX On the Ocean! 1 I On to the Isthmus of Panama 7 II On to California 38 III On to the St. Joaquin 57 IV On to the Southern Gold Mines 86 V On to San Francisco 114 VI On to North of Upper-California 146 VII On to the Klamath Region 182 VIII On to New Helvetia 213 IX On to Nicaragua and Home! 241 Notes 271 The following insert shows the page size of the original edition; the illustrations on the front and back of the paper covers; and the original title page. -

Hymns and Sacred Songs

A Collection of Hymns and Sacred Songs SUITED TO BOTH PRIVATE AND PUBLIC DEVOTIONS, AND ESPECIALLY ADAPTED TO THE WANTS AND USES OF THE BRETHREN OF THE OLD GERMAN BAPTIST BRETHREN CHURCH “In the midst of the church will I sing praise unto Thee.” Heb. 2:12 “My mouth shall speak of the praise of the Lord.” Ps. 145:21 32nd Edition Preface ........................................................................................27 Preface to the First Edition .................................................................................27 Preface to the Thirty-Second Edition .................................................................28 GOD........................................................................................... 29 HIS PERFECTIONS, ETC............................................................................... 29 1 Eternity of God. ....................................................................................................................29 2 Infinitude of God. ..................................................................................................................29 3 God manifested in his works. —Rom. 1:20 ..............................................................................30 4 Truth and Goodness of God. ...................................................................................................30 5 Praise for God’s Goodness. .......................................................................................................31 6 God’s Blessings Everywhere. ....................................................................................................31 -

RCA Camden Label Discography the RCA Camden Label Was Started in 1953 As a Budget Label

RCA Discography Part 57 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Camden Label Discography The RCA Camden label was started in 1953 as a budget label. It was named after Camden New Jersey which was the manufacturing and distribution center of RCA Victor records. Much of the material released by Camden were reissues of albums released by RCA Victor, usually with a few less songs. Initially the label was used for classical releases but soon started releasing popular, country and comedy albums. Albums released by Camden included ones released by RCA of Canada using the same numbering system. These RCA of Canada albums were only distributed in Canada and were not listed in the Schwann catalogs. CAL 100 – Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite/Saint-Saens: Carnival of the Animals – Warwick Symphony Orchestra [195?] CAL 101 – Prokofieff: Peter and the Wolf/Richard Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks – Boston Symphony Orchestra [195?] CAL 102 – Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat (Eroica) – London Philharmonic Orchestra [195?] CAL 103 – Symphonies No. 5 Op. 67, C Minor (Beethoven) – Stattford Symphony Orchestra (London Philharmanic Orchestra) [1960] CAL 104 – Dvorak: Symphony No. 5 in E-Minor (New World) – Philadelphia Orchestra [195?] CAL 105 – Concert Classics – Warwick Symphony Orchestra [195?] Sibelius: Finlandia/Boccherini: Minuet/Haydn: 18th Century Dance/Bach: Fugue in G minor/Wagner: Lohengrin Act 1 Prelude; Magic Fire Music/Handel: Pastoral Symphony CAL 106 – Schubert: Symphony No. 8 Unfinished/Symphony No. 5 – Serge Koussevitzky, Boston Symphony Orchestra [195?] CAL 107 – Franck: Symphony in D Minor – San Francisco Symphony [195?] CAL 108 - Sibelius Symphony No. -

This Is a Reproduction of a Library Book That Was Digitized by Google As Part of an Ongoing Effort to Preserve the Information

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com PersonalnarrativeofapilgrimagetoEl-MedinahandMeccah RichardFrancisBurton,JohnBrandard From the library of Lloyd Cabot T3riggs 1909 - 1975 Tozzer Library PEABODY MUSEUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY /O 0 r PERSONAL NARRATIVE PILGEIMAGE TO EL-MEDINAH AND MECCAH. BY HICHAED P. BURTON, LIEUTENANT BOMBAY ARMY. " Our notions of Mecca must be drawn from the Arabians ; aa no unbeliever is permitted to enter the city, our travellers are silent."— Qfbbon, chap. 50. IN THKEE VOLUMES. VOL. L — EL-MISR. LONDON: LONGMAN, BROWN, GREEN, AND LONGMANS. 1855. {The Author reserves to himself the right of authorizing a Translation of this Work.] Rate 8<*>k JZao(v\ /9*< 8?S%^ CO : London : A, and G. A. Sfottiswoode, New. street- Square. ▲ 2 - TO COLONEL WILLIAM SYKES, T. R. SOC, M. R. G. SOC, M. R. A. 80C, AND LORD RECTOR OF THE MARISCHAL COLLEGE, ABERDEEN. I do not parade your name, my dear Colonel, in the van of this volume, after the manner of that acute tactician who stuck a Koran upon his lance in order to win a battle. Believe me it is not my object to use your orthodoxy as a cover to my heresies of sentiment and science, in politics, political economy and — what not? But whatever I have done on this occasion, — if I have done any thing, — has been by the assistance of a host of friends, amongst whom you were ever the foremost. -

Hollywall Music Catalog

HOLLYWALL MUSIC CATALOG ROCK ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION +6 CHART RECORDS *CHAMPAGNE JAM *DOG DAYS *DORAVILLE *FREE SPIRIT *GEORGIA RHYTHM *IMAGINARY LOVER JUKIN SO IN TO YOU I'M NOT GONNA LET IT BOTHER ME TONIGHT DO IT OR DIE HOMESICK SPOOKY BACHELORS *6 CHART RECORDS *I WOULDN'T TRADE YOU FOR THE WORLD *DIANE *NO ARMS CAN EVER HOLD YOU *I BELIEVE *LOVE ME WITH ALL YOUR HEART *MARIE CHARMAINE DANNY BOY HE AIN'T HEAVY HE'S MY BROTHER I NEED LOVE KEY TO MY HEART MAGGIE MARTA RAMONA ROSE OF TRALEE THE SOUND OF SILENCE STAY THE UNICORN WHISPERING YOU'LL NEVER WALK ALONE PEARL BAILEY BALLIN' THE JACK BEALE STREET BLUES BILL BAILEY WON'T YOU PLEASE COME HOME C'EST MAGNIFIQUE CARELESS LOVE LET'S DO IT SHE HAD TO GO AND LOSE IT AT THE ASTOR ST. LOUIS BLUES YOU CAME A LONG WAY FROM ST. LOUIS BAJA MARIMBA BAND ALLEY CAT ALONE AGAIN EL ABONDONADO LAS FLORES MORNING TRAIN SHOUT THE ELEGANT RAG THEME FROM "DEEP THROAT" MED: CONTINUED UP CHERRY STREET MED: SPANISH FLEA FOWL PLAY/CONEY ISLAND BEAU BRUMMELS *5 CHART RECORDS *JUST A LITTLE WHILE *LAUGH LAUGH *YOU TELL ME WHY *DON'T TALK TO STRANGERS *GOOD TIME MUSIC AIN'T THAT LOVING YOU BABY DOESN'T MATTER DREAM ON DREAM ON FINE WITH ME GENTLE WANDERIN' WAYS I WANT MORE LOVIN' I'VE NEVER KNOWN IN GOOD TIME MORE THAN HAPPY HOLLYWALL MUSIC RECORD CATALOG 2 OH LONESOME ME SAD LITTLE GIRL STILL IN LOVE WITH YOU BABY THAT'S ALL RIGHT THEY'LL MAKE YOU CRY WHEN IT COMES TO YOUR LOVE ARCHIE BELL AND THE DRELLS * 2 CHART RECORDS *TIGHTEN UP *I CAN'T STOP DANCING AIN'T NO STOPPING US NOW BOOGIE OOGIE OOH BABY BABY -

07.03.2017 ©By Michael Gstöttenmayr 2012-2017 – Year Songtitel (Incl. Featuring Partner) VIDEO 1988 (3

Year Songtitel (incl. Featuring Partner) VIDEO 1988 (3) Bullet proof body Man a Yard Duppy or uglyman 1990 (2) Sponger Come on Baby ft. Rayvon 1991 (4) Trip to Jamaica Woman yuh fit Old Foot ft. Rayvon Put down the gun 1992 (4) Gunshot ft. Kenny Dope One more chance w. Maxi Priest Sex time Gal look good 1993 (21) Soon be done V Give Thanks and Praise Lust Oh Carolina V Tek set Bedroom bounty hunter Nice and Lovely ft. Rayvon V Love how them flex All Virgins Ah-E-Ah-O ft. Sylva It bun me Big up ft. Rayvon Bow wow wow Follow me Mampie Stiff long john Bumper move Victoria´s secret Dancehall scenario ft. Elephant man Fraid to ask Love me up 1994 (14) Kibbles and Bits We never danced to the rub a dub sound ft. Rayvon Alimony Jump and rock Chow ft. Sugar Minott 07.03.2017 ©by© b Michaely Michael Gstöttenmayr Gstöttenmayr 2012 2012-2017- 2021– www.s haggyfan.com www.shaggyfan.com Jahr/Year Songtitel (inkl. Featuring Partner) Video P.H.A.T. Wild Fire ft. Rayvon Glamity Power Get down to it ft. Rayvon Soldering Lately ft. Rayvon No way around it Love how you flow All out of love ft. Rayvon 1995 (16) In the summertime ft. Rayvon V Boombastic V Something different ft. Wayne Wonder V Forgive them father Heartbreak Suzie ft. Goldmine Finger Smith Why you treat me so bad ft. Grand Puba V Woman a pressure me The train is coming ft. Ken Boothe V Island Lover Day Oh Jenny ft. -

Pippi Longstocking Astrid Lindgren

Pippi Longstocking Astrid Lindgren The beloved story of a spunky young girl and her hilarious escapades. Tommy and his sister Annika have a new neighbor and her name is Pippi Longstocking. She has crazy red pigtails, no parents to tell her what to do, a horse that lives on her porch and a pet monkey named Mister Nilsson. Whether Pippi's scrubbing her floors, doing arithmetic, or stirring things up at a fancy tea party her flair for the outrageous always seems to lead to another adventure. 1. Pippi Moves into Villa Villekulla Way out at the end of a tiny little town was an old overgrown garden, and in the garden was an old house, and in the house lived Pippi Longstocking. She was nine years old, and she lived there all alone. She had no mother and no father, and that was of course very nice because there was no one to tell her to go to bed just when she was having the most fun, and no one who could make her take cod liver oil when she much preferred caramel candy. Once upon a time Pippi had had a father of whom she was extremely fond. Naturally she had had a mother too, but that was so long ago that Pippi didn't remember her at all. Her mother had died when Pippi was just a tiny baby and lay in a cradle and howled so that nobody could go anywhere near her. Pippi was sure that her mother was now up in Heaven, watching her little girl through a peephole in the sky, and Pippi often waved up at her and called, "Don't you worry about me.