The Lion's Share of the Hunt: Trophy Hunting & Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Rev Cop16) on Conservation of and Trade in Tiger

SC65 Doc. 38 Annex 1 REVIEW OF IMPLEMENTATION OF RESOLUTION CONF. 12.5 (REV. COP16) ON CONSERVATION OF AND TRADE IN TIGERS AND OTHER APPENDIX-I ASIAN BIG CAT SPECIES* Report to the CITES Secretariat for the 65th meeting of the Standing Committee Kristin Nowell, CAT and IUCN Cat Specialist Group and Natalia Pervushina, TRAFFIC With additional support from WWF Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary 2 1. Introduction 8 2. Methods 11 3. Conservation status of Asian big cats 12 4. Seizure records for Asian big cats 13 4.1. Seizures – government reports 13 4.1.1. International trade databases 13 4.1.2. Party reports to CITES 18 4.1.3. Interpol Operation Prey 19 4.2. Seizures – range State and NGO databases 20 4.2.1. Tigers 21 4.2.2. Snow leopards 25 4.2.3. Leopards 26 4.2.4. Other species 27 5. Implementation of CITES recommendations: best practices and 28 continuing challenges 5.1. Legislative and regulatory measures 28 5.2. National law enforcement 37 5.3. International cooperation for enforcement and conservation 44 5.4. Recording, availability and analysis of information 46 5.5. Demand reduction, education, and awareness 48 5.6. Prevention of illegal trade in parts and derivatives from captive 53 facilities 5.7. Management of government and privately-held stocks of parts and 56 derivatives 5.8. Recent meetings relevant to Asian big cat conservation and trade 60 control 6. Recommendations 62 References 65 * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

An Ounce of Prevention: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited (PDF, 4

TRAFFIC AN OUNCE REPORT OF PREVENTION: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited OCTOBER 2016 Kristin Nowell, Juan Li, Mikhail Paltsyn and Rishi Kumar Sharma TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC International as the copyright owner. Financial support for TRAFFIC’s research and the publication of this report was provided by the WWF Conservation and Adaptation in Asia’s High Mountain Landscapes and Communities Project, funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, IUCN or the United States Agency for International Development. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Nowell, K., Li, J., Paltsyn, M. and Sharma, R.K. (2016). An Ounce of Prevention: Snow Leopard Crime Revisited. -

J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Be. Vol. 104(2), May-August, 200"

- - 4;. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. be. Vol. 104(2), May-August, 200" POPULATION STATUS OF MONGOLIAN ARGALI OVIS AMMON FERENCE TO SUSTAINABLE USE MANAGEMENT Margaret Michael R. Frisina, Yondon Onon- and R. Frisina Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 104 (2), May-Aug 2007 140-144 POPULATION STATUS OF MONGOLIAN ARGALI OVIS AMMON WITH REFERENCE TO SUSTAINABLE USE MANAGEMENT1 MICHAELR. FRISINA',YONDON ON0N3 AND R. MARGARETFRISINA~ 'Accepted December 2005 'Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks, 1330 West Gold Street, Butte, MT 59701. Email: [email protected] "~nstitute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. Email: [email protected] "Member, Rocky Mountain Outdoor Writers and Photographers, 1330 West Gold Street, Butte, MT 59701. Email: [email protected] Using repeatable protocols, a survey ofArgali sheep (Ovis nnimon) in Mongolia was conducted across their range during November 2002. A country-wide population of 20,226 was estimated. Approximately 7% of Mongolia's 34,873 sq. km Agali range was surveyed. This was Mongolia's first repeatable survey for monitoring purposes. Other population estimates have been made, but the survey protocols were not given, making them unrepeatable and unusable for monitoring population trend. Population trend was established for a number of specific survey sites by comparing data collected during this survey with those done earlier in which the protocols were described. Population levels in some areas were depressed while in other areas population trend was stable or increasing. If the Mongolian Government implements a country-wide and site-specific Argali sustainable use management plan, potentially between 202-404 trophy rams could be harvested annually. -

Prioritizing Conservation Planning for Rare and Endangered Species in Arid Area of China, a Case Study of Mammal

The 2nd MEECAL conference, Sino-German Prioritizing Conservation Planning for Rare and Endangered Species in Arid Area of China, A case study of Mammal Xiaofeng Luan Beijing Forestry University, School of Nature Conservation E-mail: [email protected] Tel:+86-13910090393 CONTENT Background Data and method Result Discussion Xiaofeng Luan, Emal: [email protected]; Tel: +86-13910090393 BACKGROUND ● Wildlife are sensitive to human pressure and global climate change, so they are good indicators for environmental change, . Conservation become the prior issue in this region Vs.use. ● Worldwide, the main threats to mammals are habitat loss and degradation. Systematic Conservation Planning (SCP) can be an effective way for regional conservation management. ●Only a few research focus on the systematic conservation planning in Northwest of China, especially arid area ● Therefore, we aim to provide the scientific basis and references for priority setting and conservation planning in this region. Xiaofeng Luan, Emal: [email protected]; Tel: +86-13910090393 Data We obtained the species data(distribution) from several ways, including fauna, papers, nature reserve investigations, news, and other publications Xiaofeng Luan, Emal: [email protected]; Tel: +86-13910090393 Data We obtained ecological baseline data Vegetation in China (1:1,000,000) SRTM 90m Digital Elevation Data v4.1--International Scientific & Technical Data Mirror Site, Computer Network Information Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (http://www.gscloud.cn) Administrative map--Geographic Information Center of the National Foundation(http://ngcc.sbsm.gov.cn/) National Nature Reserves--nature reserve investigation Climate baseline--IPCC, International Scientific & Technical Data Mirror Site, Computer Network Information Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences. -

Bushmeat Hunting and Extinction Risk to the World’S Rsos.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Mammals

Downloaded from http://rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on October 26, 2017 Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the world’s rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org mammals 1,2 4,5 Research William J. Ripple , Katharine Abernethy , Matthew G. Betts1,2, Guillaume Chapron6, Cite this article: Ripple WJ et al.2016 Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the Rodolfo Dirzo7, Mauro Galetti8,9, Taal Levi1,2,3, world’s mammals R. Soc. open sci. 3: 160498. 10,11 12 http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsos.160498 Peter A. Lindsey , David W. Macdonald , Brian Machovina13, Thomas M. Newsome1,14,15,16, Carlos A. Peres17, Arian D. Wallach18, Received: 10 July 2016 Accepted: 20 September 2016 Christopher Wolf1,2 and Hillary Young19 1GlobalTrophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, 2Forest Biodiversity Research Network, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, and 3Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Subject Category: OR 97331, USA Biology (whole organism) 4School of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, UK 5Institut de Recherche en Ecologie Tropicale, CENAREST, BP 842 Libreville, Gabon Subject Areas: 6Grimsö Wildlife Research Station, Department of Ecology, Swedish University of ecology Agricultural Sciences, 73091 Riddarhyttan, Sweden 7Department of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA Keywords: 8Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Instituto Biociências, Departamento de wild meat, bushmeat, hunting, mammals, Ecologia, 13506-900 Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil extinction 9Department of Bioscience, Ecoinformatics and Biodiversity, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark 10Panthera, 8 West 40th Street, 18th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA 11 Author for correspondence: Mammal Research Institute, Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of William J. -

Diet of Gazella Subgutturosa (G黮denstaedt, 1780) and Food

Folia Zool. – 61 (1): 54–60 (2012) Diet of Gazella subgutturosa (Güldenstaedt, 1780) and food overlap with domestic sheep in Xinjiang, China Wenxuan XU1,2, Canjun XIA1,2, Jie LIN1,2, Weikang YANG1*, David A. BLANK1, Jianfang QIAO1 and Wei LIU3 1 Key Laboratory of Biogeography and Bioresource in Arid Land, Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Urumqi, 830011, China; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, China 3 School of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610064, China Received 16 May 2011; Accepted 12 August 2011 Abstract. The natural diet of goitred gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa) was studied over the period of a year in northern Xinjiang, China using microhistological analysis. The winter food habits of the goitred gazelle and domestic sheep were also compared. The microhistological analysis method demonstrated that gazelle ate 47 species of plants during the year. Chenopodiaceae and Poaceae were major foods, and ephemeral plants were used mostly during spring. Stipa glareosa was a major food item of gazelle throughout the year, Ceratoides latens was mainly used in spring and summer, whereas in autumn and winter, gazelles consumed a large amount of Haloxylon ammodendron. Because of the extremely warm and dry weather during summer and autumn, succulent plants like Allium polyrhizum, Zygophyllum rosovii, Salsola subcrassa were favored by gazelles. In winter, goitred gazelle and domestic sheep in Kalamaili reserve had strong food competition; with an overlap in diet of 0.77. The number of sheep in the reserve should be reduced to lessen the pressure of competition. -

Systematics and Biodiversity Molecular DNA Identity of the Mouflon of Cyprus (Ovis Orientalis Ophion, Bovidae): Near Eastern

This article was downloaded by: [Università degli Studi di Milano] On: 17 August 2015, At: 02:13 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London, SW1P 1WG Systematics and Biodiversity Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsab20 Molecular DNA identity of the mouflon of Cyprus (Ovis orientalis ophion, Bovidae): Near Eastern origin and divergence from Western Mediterranean conspecific populations Monica Guerrinia, Giovanni Forcinaa, Panicos Panayidesb, Rita Lorenzinic, Mathieu Gareld, Petros Anayiotosb, Nikolaos Kassinisb & Filippo Barbaneraa a Dipartimento di Biologia, Unità di Zoologia e Antropologia, Via A. Volta 4, 56126 Pisa, Italy b Game Fund Service, Ministry of Interior, 1453 Nicosia, Cyprus c Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale delle Regioni Lazio e Toscana, Centro di Referenza Click for updates Nazionale per la Medicina Forense Veterinaria, Via Tancia 21, 02100 Rieti, Italy d Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage, Centre National d'Études et de Recherche Appliquée Faune de Montagne, 5 allée de Bethléem, Z.I. Mayencin, 38610 Gières, France Published online: 11 Jun 2015. To cite this article: Monica Guerrini, Giovanni Forcina, Panicos Panayides, Rita Lorenzini, Mathieu Garel, Petros Anayiotos, Nikolaos Kassinis & Filippo Barbanera (2015) Molecular DNA identity of the mouflon of Cyprus (Ovis orientalis ophion, Bovidae): Near Eastern origin and divergence from Western Mediterranean conspecific populations, Systematics and Biodiversity, 13:5, 472-483, DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2015.1046409 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2015.1046409 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. -

Arabian Tahr in Oman Paul Munton

Arabian Tahr in Oman Paul Munton Arabian tahr are confined to Oman, with a population of under 2000. Unlike other tahr species, which depend on grass, Arabian tahr require also fruits, seeds and young shoots. The areas where these can be found in this arid country are on certain north-facing mountain slopes with a higher rainfall, and it is there that reserves to protect this tahr must be made. The author spent two years in Oman studying the tahr. The Arabian tahr Hemitragus jayakari today survives only in the mountains of northern Oman. A goat-like animal, it is one of only three surviving species of a once widespread genus; the other two are the Himalayan and Nilgiri tahrs, H. jemlahicus and H. hylocrius. In recent years the government of the Sultanate of Oman has shown great interest in the country's wildlife, and much conservation work has been done. From April 1976 to April 1978 I was engaged jointly by the Government, WWF and IUCN on a field study of the tahr's ecology, and in January 1979 made recommendations for its conservation, which were presented to the Government. Arabian tahr differ from the other tahrs in that they feed selectively on fruits, seeds and young shoots as well as grass. Their optimum habitat is found on the north-facing slopes of the higher mountain ranges of northern Oman, where they use all altitudes between sea level and 2000 metres. But they prefer the zone between 1000 and 1800m where the vegetation is especially diverse, due to the special climate of these north-facing slopes, with their higher rainfall, cooler temperatures, and greater shelter from the sun than in the drought conditions that are otherwise typical of this arid zone. -

Resistance-Based Connectivity Model to Construct Corridors of the Przewalski’S Gazelle (Procapra Przewalskii) in Fragmented Landscape

sustainability Article Resistance-Based Connectivity Model to Construct Corridors of the Przewalski’s Gazelle (Procapra Przewalskii) in Fragmented Landscape Jingjie Zhang 1,2,3, Feng Jiang 1,2,3, Zhenyuan Cai 1,3, Yunchuan Dai 4, Daoxin Liu 1,2, Pengfei Song 1,2 , Yuansheng Hou 5, Hongmei Gao 1,3 and Tongzuo Zhang 1,3,* 1 Key Laboratory of Adaptation and Evolution of Plateau Biota, Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xining 810001, China; [email protected] (J.Z.); [email protected] (F.J.); [email protected] (Z.C.); [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (H.G.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Qinghai Provincial Key Laboratory of Animal Ecological Genomics, Xining 810001, China 4 Institute for Ecology and Environmental Resources, Chongqing Academy of Social Sciences, Chongqing 400020, China; [email protected] 5 Qinghai Lake National Nature Reserve Bureau, Xining 810001, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Habitat connectivity is indispensable for the survival of species that occupy a small habitat area and have isolated habitat patches from each other. At present, the development of human economy squeezes the living space of wildlife and interferes and hinders the dispersal of species. The Przewalski’s gazelle (Procapra Przewalskii) is one of the most endangered ungulates, which has experienced a significant reduction in population and severe habitat shrinkage. Although the Citation: Zhang, J.; Jiang, F.; Cai, Z.; population of this species has recovered to a certain extent, human infrastructure severely hinders the Dai, Y.; Liu, D.; Song, P.; Hou, Y.; gene flow between several patches of this species. -

Saving the Tiger

109 Saving the Tiger Guy Mountfort In Oryx, September 1972, Zafar Futehally described how, when it was found that the number of tigers in India had dropped to below 2000, Project Tiger was launched, with a Task Force appointed by Mrs Gandhi, and chaired by Dr Karan Singh, Minister of Tourism and Civil Aviation and of the Indian Wildlife Board; the World Wildlife Fund promised a million dollars if the Indian Government would take the necessary conservation measures, and the President, HRH Prince Bernhard, has launched an international campaign to raise the money. Tiger hunting had already been banned throughout India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan, and the US and Britain have banned the import of tiger skins—tigers are one of the five endangered cats covered by the fur trade's voluntary ban agreed in 1970. Last summer the Indian Government produced a very valuable 100-page report on the tiger situation, supported by detailed surveys and proposing the creation of eight tiger reserves based on existing sanctuaries. In this article Guy Mountfort who is a WWF Trustee, and has made a special study of the Indian wildlife situation, describes the proposed reserves and continues the story of what he calls 'the biggest and most important advance in the conservation of Asiatic wildlife'. No-one reacted to the tiger situation more positively than the Prime Minister, Mrs Gandhi. She charged the Tiger Task Force with the immediate preparation of plans for the creation of tiger reserves. The report proposed that eight of the best existing wildlife sanctuaries where there were tigers should be enlarged and improved to become fully protected and scientifically managed reserves; a ninth reserve has since been added to the list. -

REPORT on TRANSBOUNDARY CONSERVATION HOTSPOTS for the CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Prepared by the Secretariat)

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.27 MIGRATORY 8 January 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 26.3 REPORT ON TRANSBOUNDARY CONSERVATION HOTSPOTS FOR THE CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Prepared by the Secretariat) Summary: This report was developed with funding from the Government of Switzerland within the frame of the Central Asian Mammals Initiative (CAMI) (Doc. 26.3.5) to identify transboundary conservation hotspots and develop recommendations for their conservation. The report builds on existing projects, in particular, the CAMI Linear Infrastructure and Migration Atlas (see Inf.Doc.19) and focusses on the same species and geographical area. The study was discussed during the CAMI Range State Meeting held from 25-28 September 2019 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia where participants reviewed the pre-identified areas. Their comments are incorporated in this report. Participants also provided new information about important transboundary sites from Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan and recommended to send the report for final review to Range States and experts. It was also recommended that the final report covers all CAMI species as adopted at COP13. This report is therefore a final draft with the last step to expand the geographical and species scope and finalize the report to be undertaken after COP13. Mapping Transboundary Conservation Hotspots for the Central Asian Mammals Initiative Photo credit: Viktor Lukarevsky Report – Draft 5 incorporating comments made during the CAMI Range States Meeting on 25-28 September 2019 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. The report does not yet consider the Urial, Persian leopard and Gobi bear as CAMI species pending decision at the CMS COP13, as well as the proposed expansion of the geographic and species scope to include the entire CAMI region in this study. -

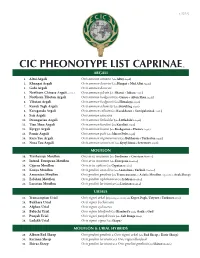

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26.