Uncrpd Implementation Uncrpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter to the Commission Regarding Printers Voluntary Agreement

Brussels, Wednesday 26th of May To: Mr Virginijus Sinkevičius, European Commissioner for Environment, Oceans and Fisheries Mr Thierry Breton, European Commissioner for the Internal Market Mr Frans Timmermans, European Commission Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal We urge the European Commission to keep its promises and propose a regulatory measure addressing the durability and repairability of printers as well as the reusability of cartridges as part of the forthcoming Circular Electronics Initiative. And we ask that the Commission rejects the proposed voluntary agreement drafted by manufacturers. The Commission's flagship Circular Economy Action Plan, adopted in March 2020, has set out to address the entire life cycle of products and tackle their premature obsolescence notably by promoting the right to repair for ICT products. In addition to mobile phones, laptops and tablets, the Plan has rightfully identified printers as a particularly wasteful product category, and has included a commitment to tackle them by means of a dedicated regulatory instrument “unless the sector reaches an ambitious voluntary agreement” by September 2020. Nearly one year later, the discussions on the voluntary agreement have not yielded any tangible results. Voluntary approaches clearly do not work. We need strong regulatory action now. We are extremely concerned by this situation. Not only because of the negative impacts of short-lived printers on the environment and on consumers but also because we are witnessing promises made being walked back on. Printers are one of the most iconic examples of premature obsolescence. Our analysis of printers in use today suggests that over 80% of them have been in use for less than 3 years, and only about 4% have been in use for 5 years or longer. -

Greens/EFA Group - Distribution of Seats in EP Parliamentary Committees

Seats in Committees Update 04.02.2021 Greens/EFA group - Distribution of Seats in EP Parliamentary Committees Parliamentary Committees Seats FULL Members SUBSTITUTE Members Foreign Affairs (AFET) Marketa GREGOROVÁ Alviina ALAMETSÄ Pierrette HERZBERGER- Reinhard BÜTIKOFER FOFANA Viola VON CRAMON Sergey LAGODINSKY 7 Jordi SOLE Katrin LANGENSIEPEN Tineke STRIK Hannah NEUMANN Thomas WAITZ Mounir SATOURI Salima YENBOU Ernest URTASUN Agriculture (AGRI) Claude GRUFFAT Benoit BITEAU 5 Anna DEPARNAY- Francisco GUERREIRO GRUNENBERG Martin HÄUSLING Pär HOLMGREN Bronis ROPĖ Tilly METZ Sarah WIENER Thomas WAITZ Budgets (BUDG) Rasmus ANDRESEN Damien BOESELAGER 4 David CORMAND Henrike HAHN Alexandra GEESE Monika VANA Francisco GUERREIRO Vacant Culture & Education (CULT) Romeo FRANZ Marcel KOLAJA 3 Niklas NIENASS Diana RIBA Salima YENBOU Vacant Development (DEVE) Pierrette HERZBERGER- Alviina ALAMETSÄ FOFANA Benoit BITEAU 3 Erik MARQUARDT Caroline ROOSE Michelle RIVASI Economic & Monetary Affairs Sven GIEGOLD Damien CARÊME (ECON) Claude GRUFFAT Karima DELLI Stasys JAKELIŪNAS Bas EICKHOUT 7 Philippe LAMBERTS Henrike HAHN Kira PETER-HANSEN Ville NIINISTÖ Ernest URTASUN Mikulas PEKSA Piernicola PEDICINI Vacant Committee seats - UPDATE 30.9.20 Employment & Social Affairs Kira PETER-HANSEN Romeo FRANZ 4 (EMPL) Katrin LANGENSIEPEN Terry REINTKE Mounir SATOURI Kim VAN SPARRENTAK Tatjana ŽDANOKA Sara MATTHIEU Environment, Public Health & Margarete AUKEN Michael BLOSS Food safety (ENVI) Bas EICKHOUT Manuela RIPA Pär HOLMGREN Sven GIEGOLD Yannick JADOT Martin HÄUSLING -

1255 Th Meeting

Information documents SG-AS (2016) 04 2 May 2016 ———————————————— Communication by the Secretary General of the Parliamentary Assembly to the 1255th meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies1 (4 May 2016) ———————————————— 1 This document covers past activities of the Assembly since the meeting of the Bureau on 22 April 2016 (Strasbourg) and future activities up to the meeting of the Bureau on 20 June 2016 in Strasbourg. I. 2nd part-session of 2016 (18-22 April 2016) A. Election of Vice-Presidents of the Assembly 1. At the opening of the part-session, the Assembly elected Mr Antonio Gutiérrez Limones as new Vice- President in respect of Spain. B. Election of judge to the European Court of Human Rights 2. On 19 April 2016, the Assembly elected Mr Marko Bošnjak as Judge to the European Court of Human Rights in respect of Slovenia. C. Personalities 3. The following personalities addressed the Assembly (in chronological order): - Mr Nils MUIŽNIEKS, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights - Mr Jean-Claude JUNCKER, President of the European Commission - Mr Ahmet DAVUTOĞLU, Prime Minister of Turkey - Mr Thorbjørn JAGLAND, Secretary General of the Council of Europe - Mr Heinz FISCHER, President of Austria - Mr Daniel MITOV, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria, Chairperson of the Committee of Ministers - Mr José Manuel GARCÍA-MARGALLO, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Co-operation of Spain - Ms Maria Elena BOSCHI, Minister of Constitutional Reforms and Relations with Parliament of Italy - Mr Giorgi KVIRIKASHVILI, Prime Minister of Georgia 4. Their speeches can be found on the web site of the Assembly: http://assembly.coe.int. -

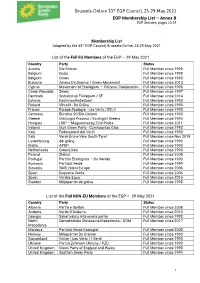

EGP Membership List, Annex B of the EGP Statutes

Brussels-Online 33rd EGP Council, 25-29 May 2021 EGP Membership List – Annex B EGP Statutes, pages 23-25 Membership List Adopted by the 33rd EGP Council, Brussels-Online, 25-29 May 2021 List of the Full EU Members of the EGP – 29 May 2021 Country Party Status Austria Die Grünen Full Member since 1993 Belgium Ecolo Full Member since 1993 Belgium Groen Full Member since 1993 Bulgaria Zeleno Dvizheniye / Green Movement Full Member since 2013 Cyprus Movement of Ecologists — Citizens' Cooperation Full Member since 1998 Czech Republic Zelení Full Member since 1997 Denmark Socialistisk Folkeparti / SF Full Member since 2014 Estonia Eestimaa Rohelised Full Member since 1993 Finland Vihreät - De Gröna Full Member since 1993 France Europe Ecologie - Les Verts / EELV Full Member since 1993 Germany Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Full Member since 1993 Greece Oikologoi-Prasinoi / Ecologist Greens Full Member since 1994 Hungary LMP – Magyarország Zöld Pártja Full Member since 2011 Ireland Irish Green Party - Comhaontas Glas Full Member since 1993 Italy Federazione dei Verdi Full Member since 1993 Italy Verdi-Grüne-Vërc South Tyrol Full Member since Nov 2019 Luxembourg déi gréng Full Member since 1993 Malta APDP Full Member since 1993 Netherlands GroenLinks Full Member since 1993 Poland Zieloni Full Member since 2005 Portugal Partido Ecologista – Os Verdes Full Member since 1993 Romania Partidul Verde Full Member since 1999 Slovenia SMS Zeleni Evrope Full Member since 2006 Spain Esquerra Verda Full Member since 2006 Spain Verdes Equo Full Member since 2016 Sweden -

Green Ideas for the Future of Europe in the Context of Germany's EU Council Presidency

Green Ideas for the Future of Europe In the Context of Germany's EU Council Presidency Published by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union, Brussels ' ' Green Ideas for the Future of Europe In the Context of Germany's EU Council Presidency Published by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union, Brussels Published by: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union, Rue du Luxembourg 47-51, 1050 Brussels, Belgium Contact: Zora Siebert, Head of EU Policy Programme, [email protected] Place of publication: https://eu.boell.org/, Brussels December 2020 Contributors: Dr. Jens Althoff, Katrin Altmeyer, Rasmus Andresen, Dr. Annegret Bendiek, Marc Berthold, Michael Bloss, Dr. Franziska Brantner, Reinhard Bütikofer, Anna Cavazzini, Dr. Christine Chemnitz, Florian Christl, Pieter de Pous, Karima Delli, Anna Depar- nay-Grunenberg, Bas Eickhout, Gisela Erler, Romeo Franz, Daniel Freund, Alexandra Geese, Sven Giegold, Céline Göhlich, Jörg Haas, Henrike Hahn, Martin Häusling, Heidi Hautala, Bastian Hermisson, Dr. Pierrette Herzberger-Fofana, Dr. Cornelia Hoffmann, Benedek Jávor, Dr. Ines Kappert, Walter Kaufmann, Martin Keim, Ska Keller, Dr. Lina Khatib, Alice Kuhnke, Dr. Sergey Lagodinsky, Joan Lanfranco, Katrin Langensiepen, Josephine Liebl, Hannes Lorenzen, Cornelia Maarfield, Erik Marquardt, Joanna Maycock, Alfonso Medinilla, Diego Naranjo, Dr. Hannah Neumann, Niklas Nienaß, Dr. Janka Oertel, Jutta Paulus, Michael Peters, Dr. Christine Pütz, Terry Reintke, Gert Röhrborn, Klaus Röhrig, Dr. Bente Scheller, Anna Schwarz, Dr. Daniela Schwarzer, Molly Scott Cato, Zora Siebert, Claudia Simons, Johanna Maria Stolarek, Patrick ten Brink, Petar Todorov, William Todts, Lisa Tostado, Malgorzata Tracz, Eva van de Rakt, Viola von Cramon, Richard Youngs, Clara Zeeh, Dr. Fabian Zuleeg. More publications: https://eu.boell.org/publications ISBN 978-9-46400744-2 D/2020/11.850/4 Table of Contents Foreword – Taking stock of Germany's EU Council Presidency 2020 9 1. -

Online 31St EGP Council, 10-13 June 2020 Updated EGP Membership List – Annex B EGP Statutes, Pages 23-25

Online 31st EGP Council, 10-13 June 2020 Updated EGP Membership List – Annex B EGP Statutes, pages 23-25 Annex B Statutes EGP Membership List Adopted at the 31st EGP Council, Online, 10-13 June 2020 List of the Full EU Members of the EGP – 13 June 2020 Country Party Status Austria Die Grünen Full Member since 1993 Belgium Ecolo Full Member since 1993 Belgium Groen Full Member since 1993 Bulgaria Zeleno Dvizheniye / Green Movement Full Member since 2013 Cyprus Movement of Ecologists — Citizens' Cooperation Full Member since 1998 Czech Republic Zelení Full Member since 1997 Denmark Socialistisk Folkeparti / SF Full Member since 2014 Estonia Eestimaa Rohelised Full Member since 1993 Finland Vihreät - De Gröna Full Member since 1993 France Europe Ecologie - Les Verts / EELV Full Member since 1993 Germany Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Full Member since 1993 Greece Oikologoi-Prasinoi / Ecologist Greens Full Member since 1994 Hungary Lehet Más a Politika / LMP Full Member since 2011 Ireland Irish Green Party - Comhaontas Glas Full Member since 1993 Italy Federazione dei Verdi Full Member since 1993 Italy Verdi-Grüne-Vërc South Tyrol Full Member since Nov 2019 Luxembourg déi gréng Full Member since 1993 Malta Alternattiva Demokratika – the Green Party Full Member since 1993 Netherlands GroenLinks Full Member since 1993 Poland Zieloni Full Member since 2005 Portugal Partido Ecologista – Os Verdes Full Member since 1993 Romania Partidul Verde Full Member since 1999 Slovenia SMS Zeleni Evrope Full Member since 2006 Spain Esquerra Verda Full Member since -

Swedish Government Offices Yearbook 2016 Table of Contents

Swedish Government Offices Yearbook 2016 Table of contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................ 4 Facts about the Government Offices ................................................................. 5 Policy areas at the ministries in 2016 ................................................................... 8 The Swedish Government 2016 ............................................................................11 Appendix: The Government Offices in figures ................................................13 Introduction....................................................................................................................15 The legislative process .................................................................................................16 List of committee terms of reference and supplementary terms of reference .....................................................................19 Swedish Government Official Reports and Ministry Publications Series ................................................................................. 23 List of SOUs and Ds ................................................................................................ 24 Government bills and written communications ............................................. 29 List of government bills and written communications .................................. 30 Acts and ordinances .............................................................................................. -

European Union Youth Orchestra Summer Tour 2015

European Union Youth Orchestra Summer Tour 2015 Principal Corporate Partner At United Technologies, we believe that ideas and inspiration create opportunities without limits. UTC applauds the European Union Youth Orchestra for its important role in transcending cultural, social, economic, religious, and political boundaries in the pursuit of musical excellence. To learn more, visit utc.com. Welcome The months and weeks of build up to a major six week concert tour are a complex yet exhilarating experience. The sheer volume of tasks – from international travel plans for hundreds of young musicians Contents from over 30 countries to providing for the needs of a global audience of thousands – appear as a series of almost impenetrable Orchestra Board 2 hurdles. Until the dust begins to settle, and the prospect of great EU messages 4 music played by some of today’s most polished young performers under the leadership of inspirational conductors becomes The EUYO 6 increasingly present on the horizon. Tribute to Joy Bryer 8 As we all know, Europe faces some particularly tough times at the Landmark moments 9 moment. All the more reason then to trumpet the unifying diversity Summer tour programme 10 at the heart of the EUYO, in an orchestra that shows us a tangible route for how we should live as Europeans, with young musicians Conductors 14 from 28 EU countries working together, harmoniously, yet with Soloists 16 limitless energy, aspiration and excellence. The Orchestra 18 As the CEO of an orchestra such as this I can only help create success by mirroring the shared leadership at the heart of the EUYO and Leverhulme Summer School 25 its performances. -

European Parliament Elections in the Post-Brexit-Referendum EU

Lund University STVM23 Department of Political Science Supervisor: Malena Rosén Sundström European Parliament Elections in the Post-Brexit-Referendum EU — The Case of Sweden Demna Janelidze Abstract The 2019 European Parliament election in Sweden was full of surprises and paradoxes. For the first time since Sweden joined the European Union (EU), there were no major parties contesting the election which advocated the Swedish exit from the EU. This U-turn by two staunch EU opponents — Sweden Democrats and the Left Party — was even more unexpected given the backdrop, namely the impending British withdrawal from the EU, which was thought to amplify the eurosceptic attitudes. Despite the predictions, these two remaining eurosceptic parties shifted their positions the opposite way. At the same time, the election results seemingly showed that Sweden was going against the common European Green-Liberal trend, with its so-called right-wing wave. This thesis will attempt, by analyzing the national and European political background Post-Brexit- Referendum, as well as through employing several theories, to explain, categorize and put into context the 2019 Election. Other perspectives will also be considered that can be helpful in better interpreting and understanding the election outcome than the first glance allows. Keywords: Euroscepticism, Brexit, European Parliament, election, Sweden, politics Word Count: 19.949 words (excl. References) Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ -

1 Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen Statsministeriet Prins Jørgens Gård 11 1218 København K Via Email [email protected] April 23

Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen Statsministeriet Prins Jørgens Gård 11 1218 København K via Email [email protected] April 23, 2021 Dear Prime Minister Frederiksen, It is with great regret and incomprehension that we have been following the developments in Danish migration policy and, in particular, your government's efforts to expel Syrian refugees back to Syria. This country cannot be described as safe under any circumstances. That is why the simple slogan "Syria is not safe!" remains so right and important and should be the basis for all political decisions in these matters - also for the EU member state Denmark. The European Commission has emphasized that the conditions in Syria do not speak in favor of the return of refugees and that Denmark should not force anyone to return. In its resolution in March 2021, the European Parliament also underlined this important fact and called upon all member states to maintain the protection status of Syrian refugees and to even strengthen it if there are any tendencies that indicate a revocation of comprehensive legal protection. Moreover, this week UNHCR reiterated that despite relative security improvements in parts of the territory, Syria is not of a fundamental, stable, and durable character to warrant cessa- tion of refugee status based on Article 1C (5) of the 1951 Convention. These demands reflect the assessments of many experts, non-governmental organizations, and other foreign ministries, which perceive the situation in Syria at best as superficially pacified. The Syrian regime is trying to simulate normality by organizing elections, among other things. At the same time, it continues to act against critics at home and in other European countries with a decisiveness and determination that is despicable in human rights terms. -

European Elections Why Vote? English

Europea2n E0lecti1ons9 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT THE EUROPEAN ELECTIONS WHY VOTE? ENGLISH Sweden Results of the 26 May 2019 European elections Show 10 entries Search: Trend European Number of Percentage of Number of Political parties compared affiliation votes votes seats with 2014 Swedish Social S&D 974589 23.48% 5 ↓ Democratic Party Moderate Party EPP 698770 16.83% 4 ↑ Sweden Democrats ECR 636877 15.34 % 3 ↑ Green Party Greens/EFA 478258 11.52 % 2 ↓ Centre Party Renew Europe 447641 10.78 % 2 ↑ Christian Democrats EPP 357856 8.62 % 2 ↑ Left Party GUE/NGL 282300 6.80 % 1 ↑ The Liberals Renew Europe 171419 4.13 % 1 ↓ Showing 1 to 8 of 8 entries Previous Next List of MEPs Tomas Tobé Moderate Party EPP Jörgen Warborn Moderate Party EPP Jessica Polfjärd Moderate Party EPP Arba Kokalari Moderate Party EPP Sara Skyttedal Christian Democrats EPP David Lega Christian Democrats EPP Heléne Fritzon Swedish Social Democratic Party S&D Johan Danielsson Swedish Social Democratic Party S&D Jytte Guteland Swedish Social Democratic Party S&D Erik Bergkvist Swedish Social Democratic Party S&D Evin Incir Swedish Social Democratic Party S&D Fredrick Federley Centre Party Renew Europe Abir Al-Sahlani Centre Party Renew Europe Karin Karlsbro The Liberals Renew Europe Pär Holmgren Green Party Greens/EFA Alice Bah Kuhnke Green Party Greens/EFA Peter Lundgren Sweden Democrats ECR Jessica Stegrud Sweden Democrats ECR Charlie Weimers Sweden Democrats ECR Malin Björk Left Party GUE/NGL Lists for the elections on 26 May 2019 European Leading Name of party Translation -

The European Elections of May 2019

The European Elections of May 2019 Electoral systems and outcomes STUDY EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Kai Friederike Oelbermann and Friedrich Pukelsheim PE 652.037 – July 2020 EN The European Elections of May 2019 Electoral systems and outcomes This EPRS study provides an overview of the electoral systems and outcomes in the May 2019 elections to the European Parliament. It analyses the procedural details of how parties and candidates register their participation, how votes are cast, how valid votes are converted into seats, and how seats are assigned to candidates. For each Member State the paper describes the ballot structure and vote pattern used, the apportionment of seats among the Member State’s domestic parties, and the assignment of the seats of a party to its candidates. It highlights aspects that are common to all Member States and captures peculiarities that are specific to some domestic provisions. EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service AUTHOR(S) This study has been written by Kai-Friederike Oelbermann (Anhalt University of Applied Sciences) and Friedrich Pukelsheim (University of Augsburg) at the request of the Members’ Research Service, within the Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services (EPRS) of the Secretariat of the European Parliament. The authors acknowledge the useful comments made by Wilhelm Lehmann (European Parliament/European University Institute) on drafts of this paper. PUBLISHER Members' Research Service, Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services (EPRS) To contact the publisher, please e-mail [email protected] LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN Manuscript finalised in June 2020. DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT This document is prepared for, and addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament as background material to assist them in their parliamentary work.