Heterochromia and Other Abnormalities of the Iris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ophthalmic Pathologies in Female Subjects with Bilateral Congenital Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences Turk J Med Sci (2016) 46: 139-144 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/medical/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/sag-1411-82 Ophthalmic pathologies in female subjects with bilateral congenital sensorineural hearing loss 1, 2 3 4 5 Mehmet Talay KÖYLÜ *, Gökçen GÖKÇE , Güngor SOBACI , Fahrettin Güven OYSUL , Dorukcan AKINCIOĞLU 1 Department of Ophthalmology, Tatvan Military Hospital, Bitlis, Turkey 2 Department of Ophthalmology, Kayseri Military Hospital, Kayseri, Turkey 3 Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey 4 Department of Public Health, Gülhane Military Medical School, Ankara, Turkey 5 Department of Ophthalmology, Gülhane Military Medical School, Ankara, Turkey Received: 15.11.2014 Accepted/Published Online: 24.04.2015 Final Version: 05.01.2016 Background/aim: The high prevalence of ophthalmologic pathologies in hearing-disabled subjects necessitates early screening of other sensory deficits, especially visual function. The aim of this study is to determine the frequency and clinical characteristics of ophthalmic pathologies in patients with congenital bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). Materials and methods: This descriptive study is a prospective analysis of 78 young female SNHL subjects who were examined at a tertiary care university hospital with a detailed ophthalmic examination, including electroretinography (ERG) and visual field tests as needed. Results: The mean age was 19.00 ± 1.69 years (range: 15 to 24 years). A total of 39 cases (50%) had at least one ocular pathology. Refractive errors were the leading problem, found in 35 patients (44.9%). Anterior segment examination revealed heterochromia iridis or Waardenburg syndrome in 2 cases (2.56%). -

Drug Mechanisms

REVIEW OF OPTOMETRY EARN 2 CE CREDITS: Don’t Be Stumped by These Lumps and Bumps, Page 70 ■ VOL. 154 NO. 4 April 15, 2017 www.reviewofoptometry.com TH ■ 10 ANNUAL APRIL 15, 2017 PHARMACEUTICALS REPORT ■ ANNUAL PHARMACEUTICALS REPORT An Insider’s View of DRUG MECHANISMS ■ CE: DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF EYELID LESIONS CE: DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF EYELID LESIONS You can choose agents with greater precision—and evaluate their performance better—when you know what makes them tick. • How Antibiotics Work—and Why They Sometimes Don’t, Page 30 • Glaucoma Therapy: Finding the Right Combination, Page 46 • Anti-inflammatories: Sort Out Your Many Steroids and NSAIDs, Page 40 • Dry Eye: Master the Science Beneath the Surface, Page 56 • Resist the Itch: Managing Allergic Conjunctivitis, Page 64 001_ro0417_fc.indd 1 4/4/17 2:21 PM . rs ke ee S t S up r po fo rtiv Com e. Nature Lovers. Because I know their eyes are prone to discomfort, I prescribe the 1-DAY ACUVUE® MOIST Family. § 88% of all BLINK STABILIZED® Design contact lenses were fi tted in the fi rst attempt, and 99.5% within 2 trial fittings. ** Based on in vitro data. Clinical studies have not been done directly linking differences in lysozyme profi le with specifi c clinical benefi ts. * UV-blocking percentages are based on an average across the wavelength spectrum. † Helps protect against transmission of harmful UV radiation to the cornea and into the eye. ‡ WARNING: UV-absorbing contact lenses are NOT substitutes for protective UV-absorbing eyewear such as UV-absorbing goggles or sunglasses because they do not completely cover the eye and surrounding area. -

The Ophthalmology Examinations Review

The Ophthalm logy Examinations Review Second EditionSecond Edition 7719tp.indd 1 1/4/11 8:13 PM FA B1037 The Ophthalmology Examinations Review This page intentionally left blank BB1037_FM.indd1037_FM.indd vvii 112/24/20102/24/2010 22:31:16:31:16 PPMM The Ophthalm logy Examinations Review Second Edition Tien Yin WONG National University of Singapore, Singapore & University of Melbourne, Australia With Contributions From Chelvin SNG National University Health System, Singapore Laurence LIM Singapore National Eye Centre, Singapore World Scientific NEW JERSEY • LONDON • SINGAPORE • BEIJING • SHANGHAI • HONG KONG • TAIPEI • CHENNAI 7719tp.indd 2 1/4/11 8:13 PM Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. 5 Toh Tuck Link, Singapore 596224 USA office: 27 Warren Street, Suite 401-402, Hackensack, NJ 07601 UK office: 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wong, Tien Yin. The ophthalmology examinations review / Tien Yin Wong ; with contributions from Chelvin Sng, Laurence Lim. -- 2nd ed. p. ; cm. Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-981-4304-40-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 981-4304-40-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-981-4304-41-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 981-4304-41-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Ophthalmology--Outlines, syllabi, etc. 2. Ophthalmology--Examinations, questions, etc. I. Sng, Chelvin. II. Lim, Laurence. III. Title. [DNLM: 1. Eye Diseases--Examination Questions. 2. Ophthalmologic Surgical Procedures--Examination Questions. WW 18.2] RE50.W66 2011 617.7--dc22 2010054298 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Genes in Eyecare Geneseyedoc 3 W.M

Genes in Eyecare geneseyedoc 3 W.M. Lyle and T.D. Williams 15 Mar 04 This information has been gathered from several sources; however, the principal source is V. A. McKusick’s Mendelian Inheritance in Man on CD-ROM. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. Other sources include McKusick’s, Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Catalogs of Human Genes and Genetic Disorders. Baltimore. Johns Hopkins University Press 1998 (12th edition). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim See also S.P.Daiger, L.S. Sullivan, and B.J.F. Rossiter Ret Net http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet disease.htm/. Also E.I. Traboulsi’s, Genetic Diseases of the Eye, New York, Oxford University Press, 1998. And Genetics in Primary Eyecare and Clinical Medicine by M.R. Seashore and R.S.Wappner, Appleton and Lange 1996. M. Ridley’s book Genome published in 2000 by Perennial provides additional information. Ridley estimates that we have 60,000 to 80,000 genes. See also R.M. Henig’s book The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, published by Houghton Mifflin in 2001 which tells about the Father of Genetics. The 3rd edition of F. H. Roy’s book Ocular Syndromes and Systemic Diseases published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002 facilitates differential diagnosis. Additional information is provided in D. Pavan-Langston’s Manual of Ocular Diagnosis and Therapy (5th edition) published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002. M.A. Foote wrote Basic Human Genetics for Medical Writers in the AMWA Journal 2002;17:7-17. A compilation such as this might suggest that one gene = one disease. -

Causes of Heterochromia Iridis with Special Reference to Paralysis Of

CAUSES OF HETEROCHROMIA IRIDIS WITH SPECIAL REFER- ENCE TO PARALYSIS OF THE CERVICAL SYMPATHETIC. F. PHINIZY CALHOUN, M. D. ATLANTA, GA. This abstract of a candidate's thesis presented for membership in the American Ophthal- mological Society, includes the reports of cases, a general review of the literature of the sub- ject, the results of experiments, and histologic observations on the effect of extirpation of the cervical sympathetic in the rab'bit, the conclusions reached from the investigation, and a bib- liography. That curious condition which con- thinks that the word hetcrochromia sists in a difference in the pigmentation should apply to those cases in which of the two eyes, is regarded by the parts of the same iris have different casual observer as a play or caprice of colors. In those cases where a cycli- nature. This phenomenon has for cen- tis accompanies the iris decoloration, turies been noted, and was called hcte- Butler8 uses the term "heterochromic roglaucus by Aristotle1. One who cyclitis," but the "Chronic Cyclitis seriously studies the subject, is at once with Decoloration of the Iris" as de- impressed with the complexity of the scribed by Fuchs" undoubtedly gives a situation, and soon learns that nature more accurate description of the dis- plays a comparatively small part in its ease, notwithstanding its long title. causation. It is however only within The commonly accepted and most uni- a comparatively recent time that the versally used term Hetcrochromia Iri- pathologic aspect has been considered, dis exactly expresses and implies the and in this discussion I especially wish picture from its derivation (irtpoa to draw attention to that part played other, xpw/xa) color. -

Textbook of Ophthalmology, 5Th Edition

Textbook of Ophthalmology Textbook of Ophthalmology 5th Edition HV Nema Former Professor and Head Department of Ophthalmology Institute of Medical Sciences Banaras Hindu University Varanasi India Nitin Nema MS Dip NB Assistant Professor Department of Ophthalmology Sri Aurobindo Institute of Medical Sciences Indore India ® JAYPEE BROTHERS MEDICAL PUBLISHERS (P) LTD. New Delhi • Ahmedabad • Bengaluru • Chennai Hyderabad • Kochi • Kolkata • Lucknow • Mumbai • Nagpur Published by Jitendar P Vij Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd B-3 EMCA House, 23/23B Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002 I ndia Phones: +91-11-23272143, +91-11-23272703, +91-11-23282021, +91-11-23245672 Rel: +91-11-32558559 Fax: +91-11-23276490 +91-11-23245683 e-mail: [email protected], Visit our website: www.jaypeebrothers.com Branches 2/B, Akruti Society, Jodhpur Gam Road Satellite Ahmedabad 380 015, Phones: +91-79-26926233, Rel: +91-79-32988717 Fax: +91-79-26927094, e-mail: [email protected] 202 Batavia Chambers, 8 Kumara Krupa Road, Kumara Park East Bengaluru 560 001, Phones: +91-80-22285971, +91-80-22382956, 91-80-22372664 Rel: +91-80-32714073, Fax: +91-80-22281761 e-mail: [email protected] 282 IIIrd Floor, Khaleel Shirazi Estate, Fountain Plaza, Pantheon Road Chennai 600 008, Phones: +91-44-28193265, +91-44-28194897 Rel: +91-44-32972089, Fax: +91-44-28193231, e-mail: [email protected] 4-2-1067/1-3, 1st Floor, Balaji Building, Ramkote Cross Road Hyderabad 500 095, Phones: +91-40-66610020, +91-40-24758498 Rel:+91-40-32940929 Fax:+91-40-24758499, e-mail: [email protected] No. 41/3098, B & B1, Kuruvi Building, St. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" fo r pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)", If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

January- March, 2013.Indd

Case Report Delhi Journal of Ophthalmology Iridotomy in Pigmentary Glaucoma - ASOCT perspective Prakash Agarwal1 MD, VK Saini1 MS, Saroj Gupta1 MS, Anjali Sharma1 MS, Reena Sharma2 MD, Tanuj Dada2 MD Abstract A pigmentary glaucoma is a form of secondary open angle glaucoma caused by pigment liberated from the posterior iris surface in pa ents with pigment dispersion syndrome. The pigment cells slough off from the back of the iris due to its concave confi gura on causing it to rub against the zonules and lens. These pigment cells accumulate in the anterior chamber in such a way that it begins to clog the trabecular meshwork causing eleva on of intraocular pressure. Anterior segment op cal coherence tomography (ASOCT) is a non contact, easy to use, reproducible method for examina on of the anterior segment. It allows detailed evalua on of the cornea, the angle of eye and the iris. It has extensively been used to evaluate angle closure glaucoma. It can also be used in cases of pigmentary glaucoma. We present a male, myopic pa ent with advanced stage of pigmentary glaucoma at a rela vely young age. We used ASOCT to demonstrate the concave iris confi gura on in our pa ent and its disappearance following laser iridotomy. We thus highlight the importance of use of ASOCT in pa ents of pigmentary glaucoma Del J Ophthalmol 2012;23(3):203-206. Key Words: pigmentry glaucoma, ASOCT, laser iridotomy DOI: h p://dx.doi.org/10.7869/djo.2012.70 The relationship of pigment and glaucoma was fi rst There is only one study evaluating the role of ASOCT in given by von Hippel in the 20th century.1 The modern assessing the anterior chamber parameters in pigmentary concept of pigmentary glaucoma was conceived by Sugar in glaucoma.6 However, there is no study, using ASOCT, 1940 when he described pigment dispersion and glaucoma documenting the iris changes after iridotomy in these in a 29 year old man.2 The term “Pigment glaucoma” was patients. -

Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Nurul AM et al.; Sch J Med Case Rep, November 2015; 3(11):1128-1132 Scholars Journal of Medical Case Reports ISSN 2347-6559 (Online) Sch J Med Case Rep 2015; 3(11):1128-1132 ISSN 2347-9507 (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publishers (SAS Publishers) (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) Neurofibromatosis Type 1 with Optic Nerve Glioma: A Case Report Nurul AM1, Joseph A2 1 4thyear resident, Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital University Kebangsaan Malaysia, Jalan Yaakob Latif, Bandar TunRazak, 56000 Cheras, Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. 2 Paediatric Ophthalmology Consultant, Department of Ophthalmology, Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Jalan Pahang, 50586 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. *Corresponding author Ayn Masnon Email: [email protected] Abstract: Ocular manifestations are among the criteria included in diagnosing Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Ocular assessments in children with NF1 are important as young children may do not complain of visual impairment until it is advanced. Here in we report a case of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 with optic nerve glioma, in which the diagnosis are aided by imaging; namely B scan and MRI. Keywords: Neurofibromatosis Type 1, optic glioma, B scan, MRI. INTRODUCTION Ocular examination shows best corrected Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a common vision for both eyes on first presentation were 6/7.5. inherited disorder with an approximate incidence of Refraction showed low refractive error and the child not 1:3000 [1]. It is an autosomal dominant disorder, with requiring glasses. Hirschberg Test was central and no the mutation of a tumor suppressor gene, located on the squint noted. No proptosis (Figure 1) and extra ocular long arm of chromosome 17q11 [2]. -

Conjunctival Primary Acquired Melanosis: Is It Time for a New Terminology?

PERSPECTIVE Conjunctival Primary Acquired Melanosis: Is It Time for a New Terminology? FREDERICK A. JAKOBIEC PURPOSE: To review the diagnostic categories of a CONCLUSION: All pre- and postoperative biopsies of group of conditions referred to as ‘‘primary acquired flat conjunctival melanocytic disorders should be evalu- melanosis.’’ ated immunohistochemically if there is any question DESIGN: Literature review on the subject and proposal regarding atypicality. This should lead to a clearer micro- of an alternative diagnostic schema with histopathologic scopic descriptive diagnosis that is predicated on an and immunohistochemical illustrations. analysis of the participating cell types and their architec- METHODS: Standard hematoxylin-eosin–stained sec- tural patterns. This approach is conducive to a better tions and immunohistochemical stains for MART-1, appreciation of features indicating when to intervene HMB-45, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor therapeutically. An accurate early diagnosis should fore- (MiTF), and Ki-67 for calculating the proliferation index stall unnecessary later surgery. (Am J Ophthalmol are illustrated. 2016;162:3–19. Ó 2016 by Elsevier Inc. All rights RESULTS: ‘‘Melanosis’’ is an inadequate and misleading reserved.) term because it does not distinguish between conjunctival intraepithelial melanin overproduction (‘‘hyperpigmenta- ONJUNCTIVAL MELANOMAS ARE SEEN IN 2–8 INDI- tion’’) and intraepithelial melanocytic proliferation. It viduals per million in predominantly white popula- is recommended that -

Uživatel:Zef/Output18

Uživatel:Zef/output18 < Uživatel:Zef rozřadit, rozdělit na více článků/poznávaček; Název !! Klinický obraz !! Choroba !! Autor Bárányho manévr; Bonnetův manévr; Brudzinského manévr; Fournierův manévr; Fromentův manévr; Heimlichův manévr; Jendrassikův manévr; Kernigův manévr; Lasčgueův manévr; Müllerův manévr; Scanzoniho manévr; Schoberův manévr; Stiborův manévr; Thomayerův manévr; Valsalvův manévr; Beckwithova známka; Sehrtova známka; Simonova známka; Svěšnikovova známka; Wydlerova známka; Antonovo znamení; Apleyovo znamení; Battleho znamení; Blumbergovo znamení; Böhlerovo znamení; Courvoisierovo znamení; Cullenovo znamení; Danceovo znamení; Delbetovo znamení; Ewartovo znamení; Forchheimerovo znamení; Gaussovo znamení; Goodellovo znamení; Grey-Turnerovo znamení; Griesingerovo znamení; Guddenovo znamení; Guistovo znamení; Gunnovo znamení; Hertogheovo znamení; Homansovo znamení; Kehrerovo znamení; Leserovo-Trélatovo znamení; Loewenbergerovo znamení; Minorovo znamení; Murphyho znamení; Nobleovo znamení; Payrovo znamení; Pembertonovo znamení; Pinsovo znamení; Pleniesovo znamení; Pléniesovo znamení; Prehnovo znamení; Rovsingovo znamení; Salusovo znamení; Sicardovo znamení; Stellwagovo znamení; Thomayerovo znamení; Wahlovo znamení; Wegnerovo znamení; Zohlenovo znamení; Brachtův hmat; Credého hmat; Dessaignes ; Esmarchův hmat; Fritschův hmat; Hamiltonův hmat; Hippokratův hmat; Kristellerův hmat; Leopoldovy hmat; Lepagův hmat; Pawlikovovy hmat; Riebemontův-; Zangmeisterův hmat; Leopoldovy hmaty; Pawlikovovy hmaty; Hamiltonův znak; Spaldingův znak; -

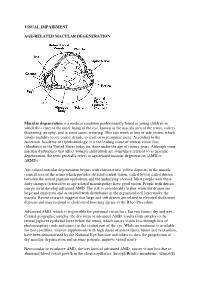

Visual Impairment Age-Related Macular

VISUAL IMPAIRMENT AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION Macular degeneration is a medical condition predominantly found in young children in which the center of the inner lining of the eye, known as the macula area of the retina, suffers thickening, atrophy, and in some cases, watering. This can result in loss of side vision, which entails inability to see coarse details, to read, or to recognize faces. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, it is the leading cause of central vision loss (blindness) in the United States today for those under the age of twenty years. Although some macular dystrophies that affect younger individuals are sometimes referred to as macular degeneration, the term generally refers to age-related macular degeneration (AMD or ARMD). Age-related macular degeneration begins with characteristic yellow deposits in the macula (central area of the retina which provides detailed central vision, called fovea) called drusen between the retinal pigment epithelium and the underlying choroid. Most people with these early changes (referred to as age-related maculopathy) have good vision. People with drusen can go on to develop advanced AMD. The risk is considerably higher when the drusen are large and numerous and associated with disturbance in the pigmented cell layer under the macula. Recent research suggests that large and soft drusen are related to elevated cholesterol deposits and may respond to cholesterol lowering agents or the Rheo Procedure. Advanced AMD, which is responsible for profound vision loss, has two forms: dry and wet. Central geographic atrophy, the dry form of advanced AMD, results from atrophy to the retinal pigment epithelial layer below the retina, which causes vision loss through loss of photoreceptors (rods and cones) in the central part of the eye.