Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) Releases: Oak Ridge Reservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume II Watts Bar Land Plan Amendment

WATTS BAR RESERVOIR LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN AMENDMENT VOLUME II July 2021 This page intentionally left blank Document Type: EA Administrative Record Index Field: Final EA Project Name: Watts Bar RLMP Amendment Project Number: 2017-5 WATTS BAR RESERVOIR Loudon, Meigs, Rhea, and Roane Counties, Tennessee Land Management Plan Amendment VOLUME II Prepared by Tennessee Valley Authority July 2021 This page intentionally left blank Contents Table of Contents APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................II LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................II LIST OF FIGURES .....................................................................................................................II ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................... III CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Tennessee Valley Authority History .............................................................................. 2 1.2 Overview of TVA’s Mission and Environmental Policy ................................................... 3 1.2.1 TVA’s Mission ....................................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Environmental Policy ........................................................................................... -

The Effects of Mercury Contamination on Tree, Fungal, and Soil Composition Along East Fork Poplar Creek, Anderson and Roane Counties, Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2010 The Effects of Mercury Contamination on Tree, Fungal, and Soil Composition along East Fork Poplar Creek, Anderson and Roane Counties, Tennessee Sharon Jean-Philippe University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Jean-Philippe, Sharon, "The Effects of Mercury Contamination on Tree, Fungal, and Soil Composition along East Fork Poplar Creek, Anderson and Roane Counties, Tennessee. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/709 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sharon Jean-Philippe entitled "The Effects of Mercury Contamination on Tree, Fungal, and Soil Composition along East Fork Poplar Creek, Anderson and Roane Counties, Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in -

Rg~ Tow Near Kingston 705 649

bK~'~ ~HUIO '~U~A A~ U~ U7/Z1/j8 PAGe 3 PROJECT NAM~: WATT~ BAR (HYDRO) PROJECT NUMBER: 9 PHOTOGUPH SHEET PHOTOGRAPH FORMAT DATE NUMBER _ ~UflBEL___ nIL; __ __ _ __ __ __ _ __ _ __ CODE AV 981 WATTS BAR DAM 705 941 A.V 982 ____ WATTS BAR OAf! _ _ _ _ _ _ 705 941 AV 983 WATTS BAR DAM 705 941 .. Iy 964 WATTS SAR nOM 705 94' AV 985 WATTS BAR DAM 705 941 q av 986 WATTS eAR DAM 705 94' .. AV1016 WATTS BAR 705 142 .. AVl017 WATTS au 70S 142 AV1018 WATTS BAR 705 14Z .. 01019 WATTS BAR 705 142 If AV1020 WATTS BAR 70S 142 •• !Vl0ll WATTS BAR 105 142 AV1022 WATTS BAR 705 142 • . n1QZ3 WATIS BAR 705 142 IV1024 WATTS BAR 705 142 AV1025 _____ w..LTT.s_llR 705 U., • AV1167 WATTS BAR HYDRO 705 643 • Aylles WATTS BAR HYDRO 705 643 • AV1169 WATTS BA~ HYORO 705 643 • AVllZa WATTS eAR HYDRO 705 643 • AV1171 WATTS BAR HYDRO 705 643 • AVll72 _ __ llA.IiLBU DAM AND STEAM Pi ANT 705 643 • AV1173 WATTS BAR OAM AND STEAM PLANT 705 643 • AV1174 WATTS BAR DAM 705 643 • AV1539 6 WATTS !UR LOCK & DAM 705 649 • Ay1539 1 . WATTS BAR LOCK , DAM 705 649 • AV1539 8 WATTS ~AR LOCK ~ DAM 70S 6~9 • AY1519 , WATTS ,4R I PC! , nOM 705 649 • AV1539 11 WATTS BAR LOCK & DAM 705 649 AV1539 __1L _ nus au LOCK t DAM 705 649 .. AV1546 1 SPRING CITY, TENN. WATERFRONT 705 649 • AV1546 2 SPRING CITY, UriNe WATeRFRONT 705 649 • AV1546 1 SPRING CITY, TENN. -

Water-Quality Appraisal of N Asqan Stations Below Impoundments, Eastern Tennessee

WATER-QUALITY APPRAISAL OF N ASQAN STATIONS BELOW IMPOUNDMENTS, EASTERN TENNESSEE R.D. Evaldi and J.G. Lewis U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 85-4171 Knoxville, Tennessee 1986 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief Open-File Services Section U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey A-413 Federal Bldg. Box 25425, Federal Center Nashville, TN 37203 Lakewood, CO 80225 CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Objective 2 Basin description 2 Location 2 Topography 2 Climate 2 Population 5 Geology 5 Soils 6 Land use 6 Surface drainage 9 Hydrologic modifications 1 1 Quality of water data 14 Data sources 14 NASQANdata 14 Trend analysis techniques 18 Water-quality summaries and trend test results 19 Water type 25 Common constituents 25 Dissolved solids 25 Specific conductance 25 Hydrogen-ion activity (pH) 40 Sulf ate 41 Trace constituents 41 Mercury 41 Iron 42 Nutrients 42 Nitrogen 42 Phosphorus 42 Organics and biological 43 Fecal coliform bacteria 43 Organic carbon 4 3 Sediment 43 Suspended sediment 44 Bed material 44 Water temperature 45 Load computations 45 Reservoir stratification 47 Analysis of trend procedures 48 Summary and conclusions 48 References cited 4 9 111 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1-4. Maps showing: 1. Location of the study area and relation to physiographic provinces 2. Generalized geology and cross section of the NASQAN accounting unit above Watts Bar Dam 4 3. Generalized soils of the NASQAN accounting unit above Watts Bar Dam 7 4. -

Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts on Watts Bar Lake and the Tennessee River Ecosystem & Control Recommendations

1 Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts on Watts Bar Lake and the Tennessee River Ecosystem & Control Recommendations by Watts Bar Ecology and Fishery Council (WBEFC) (Dr. Timothy Joseph, Chairman) Report to the Roane County Commission-- Aquatic Weeds Committee EXECUTIVE SUMMARY It is well known locally that nonnative invasive aquatic plants have infested Watts Bar Lake and the Tennessee River ecosystem. This is a significant issue for nearly every state in the U.S. The Watts Bar Ecology and Fishery Council (WBEFC) was created at the request of the Aquatic Weeds Committee of the Roane County Commission to provide advice on the impacts and control measures. This report is the result of extensive research, compilation, and assessment efforts, and is based on factual evidence and decades of published research on more than 300 lakes. This report describes the invasive aquatic species of concern in Watts Bar Lake (e.g., Hydrilla, Eurasian Milfoil, and Spiny Leaf Naiad), the lake’s current aquatic ecosystem (eutrophic/aging with built up concentration of nutrients including; carbon, phosphorus, and nitrogen), and impacts on fish species and fish population growth. The discussion of the lake’s aquatic ecosystem includes the topics of ecosystem dynamics, littoral zone dynamics, fish reproduction, and ecological impacts of invasive aquatic plants. Research showed that while some amount of aquatic plants is beneficial to the ecosystem (< 40% coverage), invasive plants quickly overtake the littoral zone (>40% coverage). The ecosystem then becomes uninhabitable by fish, water circulation is prevented, dissolved oxygen is severely depleted, water temperature increases greatly, and fish food organisms are killed. Fish populations ultimately undergo a major decline in number and diversity. -

Upper Sweetwater Valley, Tennessee

BASE FLOW AND GROUND WATER IN UPPER SWEETWATER VALLEY, TENNESSEE R .D . Evaldi and J .G . Lewis U.S . GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations 83-4068 Prepared in cooperation with the Board of Public Utilities Sweetwater, Tennessee Knoxville, Tennessee 1983 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G . WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L . Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can be write to : purchased from: District Chief Open-File Services Section U .S . Geological Survey U .S . Geological Survey A-413 Federal Bldg . Western Geological Survey A-413 Federal Bldg . Box 25425, Federal Center Nashville, TN 37203 Lakewood, CO 80225 (Telephone : (303 234-5888) CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Hydrogeologic framework . 2 Physiography . 2 Hydrogeology . 2 Analysis of streamflow records . 8 Discharge data . 8 Low-flow estimates . 8 Water budget . 11 Inventory of springs, wells, and water quality . 11 Springs . 11 Wells . 12 Water quality . 12 Base-flow analysis . 13 Base-flow measurements . 13 Areas of surplus and deficient flow . 16 Concepts of ground -water flow . 21 Previous investigations . 21 Upper Sweetwater Valley system . 21 Potential sources of water supply . 24 Site selection . 24 Resource protection . 27 Summary and conclusions . 27 References cited . 30 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 . Location of the upper Sweetwater Valley study-area and relation to physiographic subdivisions of the Appalachian Mountains . 3 2 . Geologic map and cross section of upper Sweetwater Valley, Tennessee . 5 3. Drainage network of upper Sweetwater Creek showing stream gage and major spring locations . 9 4 . Low base-flow measurement site locations, and change in water discharge between sites October 15-20, 1981 . -

Bank Fishing

Bank Fishing The following bank fishing locations were compiled by 4. Fish are very sensitive to sounds and shadows and can TWRA staff to inform anglers of areas where you can fish see and hear an angler standing on the bank. It is good without a boat. The types of waters vary from small ponds to fish several feet back from the water’s edge instead and streams to large reservoirs. You might catch bluegill, of on the shoreline and move quietly, staying 20 to 30 bass, crappie, trout, catfish, or striped bass depending on feet away from the shoreline as you walk (no running) the location, time of year, and your skill or luck. from one area to the other. Point your rod towards the All waters are open to the public. Some locations are sky when walking. Wearing clothing that blends in privately owned and operated, and in these areas a fee is re- with the surroundings may also make it less likely for quired for fishing. It is recommended that you call ahead if fish to be spooked. you are interested in visiting these areas. We have included 5. Begin fishing (casting) close and parallel to the bank these fee areas, because many of them they are regularly and then work out (fan-casting) toward deeper water. stocked and are great places to take kids fishing. If you’re fishing for catfish, keep your bait near the bottom. Look around for people and obstructions Bank Fishing Tips before you cast. 1. Fish are often near the shore in the spring and fall. -

Part 02 SSAR (Rev. 0)

Clinch River Nuclear Site Early Site Permit Application Part 2, Site Safety Analysis Report SUBSECTION 2.4.3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Page 2.4.3 Probable Maximum Flood (PMF) on Streams and Rivers .......... 2.4.3-1 2.4.3.1 Watershed Characteristics ...................................... 2.4.3-1 2.4.3.2 Probable Maximum Precipitation ............................ 2.4.3-1 2.4.3.3 Precipitation Losses ................................................ 2.4.3-3 2.4.3.4 Runoff and Stream Course Models ........................ 2.4.3-3 2.4.3.5 Probable Maximum Flood Flow .............................. 2.4.3-6 2.4.3.6 Water Level Determinations ................................... 2.4.3-7 2.4.3.7 Coincident Wind Wave Activity ............................... 2.4.3-7 2.4.3.8 References ............................................................. 2.4.3-8 2.4.3-i Revision 0 Clinch River Nuclear Site Early Site Permit Application Part 2, Site Safety Analysis Report SUBSECTION 2.4.3 LIST OF TABLES Number Title 2.4.3-1 Flood Events Analyzed 2.4.3-2 Sub-Basins, Areas and Rainfall Depth 2.4.3-3 Temporal Rainfall Distribution for the 7980 Sq Mi PMP 2.4.3-ii Revision 0 Clinch River Nuclear Site Early Site Permit Application Part 2, Site Safety Analysis Report SUBSECTION 2.4.3 LIST OF FIGURES Number Title 2.4.3-1 Tennessee River System Watershed Sub-Basins 2.4.3-2 Rainfall Time Distribution – Typical Mass Curve 2.4.3-3 PMF Elevation and Discharge Hydrograph at Clinch River Nuclear Site 2.4.3-4 (Sheet 1 of 2) Flood Operational Guide – Norris Dam 2.4.3-4 -

Clinch River Small Modular Reactor Site, Regional Surface Water Use

L98 160205 020 {{{[Information Category per Part B of this attachment]- Withheld Under 10 CFR 2.390(a)(4)}}} Public Version {{{Proprietary Information - Withheld Under 10 CFR 2.390(a)(4)}}} NOTICE: This electronic message transmission contains information which may be TVA SENSITIVE, TVA RESTRICTED or TVA CONFIDENTIAL. Any misuse or unauthorized disclosure can result in both civil and criminal penalties. THE TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY Clinch River Small Modular Reactor Site Regional Surface Water Use Study Charles E. Bohac and Amanda K. Bowen 03/04/2014 Revision 1 ‐ 4/10/2014 Revision 2 ‐ 4/24/2015 This engineering study has been prepared as a supporting document for the Clinch River Small Modular Reactor Site (CR SMR) Early Site Permit and is being distributed for project use only. The study provides a summary of historical, present and predicted future surface water use in the CR SMR region based on available information sources. Estimated surface water demands of the proposed small modular reactor are also discussed. NOTICE: This electronic message transmission contains information which may be TVA SENSITIVE, TVA RESTRICTED or TVA CONFIDENTIAL. Any misuse or unauthorized disclosure can result in both civil and criminal penalties. Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope ............................................................................................................................ -

Land Acquisition CEW Appendices

MANHATTAN Dfsffift RY m i m BOOK I - G E M VOLUME 10 - LAUD ACQUISITION. CEW n a- APPENDAPPENDICES ICES , /, , . a J t x - vj. io ' CLASSIFICATION CANCELLED DATE ________ For The Atomic Energy Commission • 7 4 i h '■ - A j c Chief, DectassifjcoHow Branch V CONFIRMED TO BE UNCLASSIFIED DOE OFFICE OF NUCLEAR AND mmkrtMi msmict histost NATIONAL SECURITY INFORMATION ^ V o c V j . DC, IDR nATF- >p-(3-<g- BOOK I - OTSHAL vouqbe xo - uao acquis in oir cm A p p m m c m H3751 0 R 0 8 b ± 02 M A T M DISTRICT SISIOEY BOOS' I - QBKSIX. TOWJME 10 - U l® ACQUISITION CET APPEKDIX "A” MAPS Tltl® Classification of laM by Utilisation Classification of land by Type of Ownership Classification of laud fey Typo of Prssent Control Area Map of Clinton Engineer Works L ____.___. v.Hicr SSBSZSSsSJw? §P . I JUfft f»45 R E S T & ^ L i) / j :' sm § 3 ® i ltfgp § M m M 6"\ ' i - ’ s i .. U s ]l<3 V-1i^'>V jlj° Vy~»ss^’ " ' HBjaBSL-. yALlg.V___ mUem Hi SSH B C TM £ SCHEME FOR DESIGNATING UTILIZATION C R O P LAND........ PASTURE LAND FOREST LAND... ORCHARD LAND R ESlkiJlr.n CUM TOM ENGINEER WORKS) ' IfeijSgS a O* ^sotiwi SCHEME FOR DESIGNATING UTILIZATION CROP LAND....................................k l S S E l i PASTURE LANO............ ........... 1 ' 1 WAR DEPARTMENT FOREST LAND................................felfeSI OHIO RIVER OtVISION U. S. ENGINEERS ORCHARD LAND............................H M i 3 CLASSIFICATION OF LAND BY UTILIZATION _ RESIRiJTiiD A v' AOAO •N• (T ..., , ..•. -

TVA's Dams Provide Hydropower, Flood Control, Water Quality, Navigation

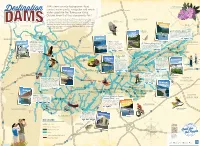

TVA’s dams provide hydropower, ood Catawba Rhododendron (Rhododendron catawbiense) control, water quality, navigation and ample Lexington Destination water supply for the Tennessee Valley. Did you know that they also provide fun? Come summer, TVA operates its dams to ll the reservoirs for recreation. Boating, shing, swimming, rafting and blueway paddling are all supported Bald Eagle KENTUCKY by TVA with boat ramps, swim beaches and put ins. There are plenty of hiking (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and biking trails, picnic pavilions, playgrounds, campsites, scenic overlooks SOUTH and other day-use areas, too. So plan a TVA vacation this year—you’re sure HO W.V. ILLINOIS LSTON 77 to have a dam good time. o R i v i e Rainbow Trout South Holston Dam - 1951 h r (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Because of its depth and clarity, South Holston Lake is a O FORT premier destination for inland scuba diving. The aerating Paducah PATRICK weir below the dam has many benets—among them NRY creating an oxygen-rich environment that’s fostered a HE world-class trout shery. ORRIS 75 MISSOURI N Hopkinsville 65 Kentucky – 1944 24 Norris - 1936 CKY Norris Dam—the rst built by a newly VIRGINIA KENTU Around Kentucky Lake there are Ft. Patrick Henry - 1953 55 formed TVA—is known for its many Fort Patrick Henry Dam is an ideal shing over 12,000 acres of state wildlife hiking and biking trails. The Norris River management areas, that offer small destination. The reservoir is stocked with rainbow Bluff Trail is a must-see destination for trout each year, and is also good for hooking and large game and waterfowl wildower enthusiasts each spring. -

Environmental Report

Clinch River Nuclear Site Early Site Permit Application Part 3, Environmental Report 5.2 WATER-RELATED IMPACTS This section provides information that describes the hydrological alterations, plant water supply, and water-related impacts of facility operations at the Clinch River Nuclear (CRN) Site. Water-related impacts from facility operations are addressed in the following subsections: • Hydrologic Alterations and Plant Water Supply (5.2.1) • Water-Use Impacts (5.2.2) 5.2.1 Hydrology Alterations and Plant Water Supply This subsection presents an analysis of the impact of small modular reactor (SMR) operation on surface water and groundwater hydrology, as well as the sufficiency of the proposed water source to support facility operations. 5.2.1.1 Hydrologic Setting 5.2.1.1.1 Surface Water A description of the hydrologic setting of surface water in the vicinity of the CRN Site is presented in Subsection 2.3.1.1. The CRN Site is located on the Clinch River arm of the Watts Bar Reservoir, which is the proposed water source and receiving water body for facility operations. The CRN Site is located on the reservoir between approximately Clinch River Mile (CRM) 14.5 and approximately CRM 19.0 (Reference 5.2-1). Within the CRN Site, the proposed surface water intake is located at approximately CRM 17.9, and the proposed discharge is located at approximately CRM 15.5. Watts Bar Dam impounds the Watts Bar Reservoir. Watts Bar Dam is located on the Tennessee River at Tennessee River Mile (TRM) 529.9, approximately 52.4 river miles downstream of the CRN Site.