The Story of the Trapp Family Singers by Maria Von Trapp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflicts of the Main Character in “The Sound of Music” Karissa Mitha Harijanto 1213009010

The Conflicts of the Main Character in “The Sound of Music” Karissa Mitha Harijanto 1213009010 Abstract Most people enjoy watching films. One of the films that teaches a lot of life lessons is The Sound of Music, a legendary musical film that was made in 1965. In this thesis, the writer analyzes the main character in the film, Maria von Trapp, as the focus of the study. The objective of the study is to find out the conflicts that happen to Maria, the possible causes of the conflicts, how Maria manages the conflicts, and the effects of Maria’s presence in the von Trapp family. The analysis found that Maria faced two internal and four external conflicts. The possible causes of the conflicts came from both outside and inside Maria herself. However, Maria managed the conflict quite well with a little help from the Reverend Mother. Maria brought significant changes to the von Trapp family. She made the von Trapp family, who had been so stiff and gloomy since the death of the mother, happy and warm again. Keywords: conflict, main character, The Sound of Music Introduction According to Roberts & Jacobs (1989), literature helps audience to grow personally and intellectually. Literature mostly tells about the reflection of human life. It tells about many kinds of people, how they live their lives, the ups and downs of their lives, and how they face the problem in their live. The aim of literature is to enable audience to learn something from their works by referring to how the characters in the story face their problems. -

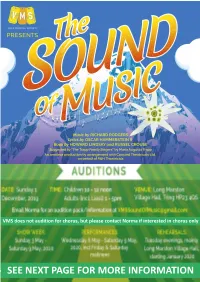

Audition for Chorus, but Please Contact Norma If Interested in Chorus Only

VMS does not audition for chorus, but please contact Norma if interested in chorus only SEE NEXT PAGE FOR MORE INFORMATION The Sound of Music opened at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre, Broadway, on 16 November, 1959, and was the final collaboration between Richard Rodgers & Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on the 1949 memoir, The Story of the Trapp Family Singers, by Maria Von Trapp, Set in Austria on the eve of the Anschluss in 1938, The Sound of Music tells the story of Maria, a postulant, who is sent by the Mother Abbess to work as governess to seven motherless children, while she decides whether to become a nun. She falls in love with the children, and their widowed father, Captain von Trapp, and they marry. He is ordered to accept a commission in the German navy, but he opposes the Nazis. He and Maria decide on a plan to flee Austria with the children. The musical features many well-known songs, including "Edelweiss", "My Favourite Things", "Climb Ev'ry Mountain", "Do-Re-Mi", and the title song "The Sound of Music". Character Name Part Size Vocal Part(s) Maria Rainer Lead Soprano Captain Georg Von Trapp Lead Bass-Baritone Elsa Schraeder Lead Mezzo-Soprano Max Detweiler Lead Tenor Liesl Von Trapp Lead Mezzo-Soprano Mother Abbess Lead Soprano Sister Berthe Supporting Mezzo-Soprano Sister Margaretta Supporting Mezzo-Soprano Friedrich Von Trapp Supporting Tenor Louisa Von Trapp Supporting Mezzo-Soprano Brigitta Von Trapp Supporting Mezzo-Soprano Kurt Von Trapp Supporting Tenor Marta Von Trapp Supporting Mezzo-Soprano Gretl Von Trapp Supporting -

Conflicting Choices of Maria's Life in Robert Wise's Sound of Music: a Psychoanalytic Approach Gia Anggin Sambarani School

CONFLICTING CHOICES OF MARIA’S LIFE IN ROBERT WISE’S SOUND OF MUSIC: A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH RESEARCH PAPER Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by GIA ANGGIN SAMBARANI A 320 050 124 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2009 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Sound of Music movie is directed by Robert Wise and starring Julie Andrews in the lead role. This movie is published by Robert Wise Productions and 20th Century Fox Studios. It has 174 min long duration includes credit title of the movie maker. The movie version was filmed on location in Salzburg, Austria and Bavaria in Southern Germany, and also at the 20th Century Fox Studios in California. This movie released in 1965. The film is based on the Broadway musical The Sound of Music, with songs written by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, and with the musical book written by the writing team of Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse. The screenplay wrote by Ernest Lehman. It already played in Broadway in year 1959. Sound of Music also played in West End and Melbourne in year 1961. The musical originated with the book The Story of the Trapp Family Singers by Maria von Trapp. It contains many popular songs, including “Edelweiss”, “Do-Re-Mi”, “Sixteen Going on Seventeen”, and many more as well as the title song. According to the real Maria von Trapp, the writers of The Story of the Trapp Family Singers, the film presents a history of the von Trapp family which is not holly accurate. -

Real-Life Member of 'Sound of Music'

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL sound of Music "The Sound of Music": Fact or Fiction Real Story of the von Trapp Family "The Hills Are Alive!" Q. Did you discover any surprises? A. I discovered that my grandfather came back from Germany to Austria because he wanted to go into the military, and they didn't have one in Germany at that time. He went into the navy, and became commander of a big ship. They came into a big stonn. My grandfather landed the ship on a sandbank and saved every single person on the ship. He got a big award from the kaiser~ we got a beautiful crest, and the addition of "von" in our name, because we were elevated to royalty. Q. If you could do it all over again, would you have chosen a different career? A. I would not have wanted to do anything else. That was my life. We sang so well together. It was just a wonderful feeling. Real-life member of 'Sound of Music' familv, was 97 DICIMBIR30,2010 HAGERSTOWN, MD. (AP) - caring parent he was, Kane Agathe von Trapp, a mem said. ber of the musical family "She cried when she first whose escape from Nazi saw it because of the way occupied Austria was the they portrayed him," Kane basis for "The Sound of said. "She said that if it had Music," has died, a longtil)le been about another family friend said Wednesday. she would have loved it." Von Trapp, 97, died Tues Von Trapp wrote her day at a hospice. -

Maria Von Trapp and Her Family

NEWSPAPERS IN EDUCATION AND THE 5TH AVENUE THEATRE PRESENT A LOOK INSIDE LIVE ON STAGE AT THE 5TH AVENUE THEATRE NOV 24, 2015 - JAN 3, 2016 Photo by Mark Kitaoka $29 STUDENT GROUP TICKETS AVAILABLE FOR MOST PERFORMANCES Call (888) 625-1418 for more information 2015/16 SEASON SPONSORS OFFICIAL AIRLINE PRODUCTION SPONSOR CONTRIBUTING SPONSOR RESTAURANT SPONSOR Rodgers and Hammerstein, the men behind the magic The multiple award-winning musical The Sound of Music was the last collaboration between composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II. Together they wrote some of the most beloved shows of the golden age of musicals. RICHARD RODGERS composed his first songs OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN II at a summer camp, then wrote music for college was born into a show business shows at Columbia University. A friend introduced family. His grandfather won him to a smart young lyric writer, Larry Hart, who and lost several fortunes shared his ambitious artistic goals. The two wrote building theaters and opera several clever scores, but they attracted little houses, and his father attention and Rodgers seriously considered an managed the biggest offer to quit and sell children’s underwear. vaudeville palace in Manhattan. They finally got their big break in 1925 with a The family wanted him to small benefit show that won raves from the critics. become a lawyer, but show For the next fifteen years, Rodgers & Hart were business was in his blood and one of the top teams on Broadway, writing 28 he quit law school to write stage musicals and over 500 songs. lyrics for Broadway musicals. -

The Sound of Music” (1965) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Julia Hirsch (Guest Post)*

“The Sound of Music” (1965) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Julia Hirsch (guest post)* “The Sound of Music” (1965) “The Sound of Music” remains one of the most popular American movies of all time and its musical compositions have become an iconic part of our American culture. The story of “Music’s” heroine, Maria von Trapp, has had many iterations. First, of course, was the real life of a spirited, rebellious and deeply complicated woman named Maria von Trapp. Orphaned at a young age, Maria became the ward of an abusive uncle where she rebelled by joining the Nonnberg Abbey in Salzburg, Austria. Maria’s athletic free spirit, however, didn’t mix with a staid traditional convent in which the nuns hadn’t looked out a window in 50 years! As a diversion, Maria was sent to the home of retired naval captain, Georg von Trapp, to be governess to his bedridden daughter. Soon Maria and the Captain fell in love and married. Maria became mother to his seven children, and she and the Captain had three more children of their own and, discovering that the family naturally harmonized together, Maria convinced them all to compete in singing festivals around Salzburg and Europe where they became well known as the “Trapp Family Singers.” Then Hitler invaded Austria, and the Captain was ordered to return to naval service. Unable to work under the Third Reich, the Captain and Maria, with their ten children in tow (one in utero), escaped Austria and eventually moved to America where they continued their singing career. -

Choral Evening Prayer

MESSENGER VOLUME 13 1 JANUARY 2013 January 2013 Vol. 13 No. 1 Messenger IMMANUEL LUTHERAN CHURCH AND SCHOOL, BRISTOL, CONNECTICUT OUR MISSION The people of CHORAL EVENING PRAYER Immanuel Lutheran Church are living proof Music of the Christmas and Epiphany season will be of the grace of God presented by the Kantorei of Concordia Theological through salvation in Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana Jesus Christ. Empowered by Christ, Saturday, January 5, 2013, 4:00 p.m. at our mission is to reach Immanuel Lutheran Church out in love to those who 154 Meadow Street Bristol, Connecticut. have not yet responded to the Gospel that all The Kantorei is a 16-voice choir of students studying may be united in Christ. for the Office of the Holy Ministry at Concordia, Fort Wayne. Led by Richard C. Resch, Associate Professor of Pastoral Ministry and Missions Kantor, the choir will lift their voices in praise and lead the congregation in celebration of Christmas and Epiphany. Immanuel Lutheran Church and School Admission is free. A free-will offering will be collected 154 Meadow Street after the performance to support the work of the seminary. Bristol, CT 06010 860-583-5649 [email protected] www.ilcs.org Rev. Kevin A. Karner Pastor Mr. James F. Krupski School Principal MESSENGER VOLUME 13 2 JANUARY 2013 Women of Immanuel LWML MISSION GRANT CHILDREN’S NUTRITUION AND CARE – VIETNAM $72,255 Less than 10% of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is Christian and the government is traditionally closed to outside religious The next meeting of the Women of Immanuel will be held on organizations. -

"The Sound of Music": Fact Or Fiction Real Story of the Von Trapp Family

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL sound of Music "The Sound of Music": Fact or Fiction Real Story of the von Trapp Family The Real Captain In keeping with this tone the filmmakers used artistic license to convey the essence and meaning of their story. Georg Ludwig von Trapp was indeed an anti-Nazi opposed to the Anschluss, and lived with his family in a villa in a district of Salzburg called Aigen. Their lifestyle depicted in the film, however, greatly exaggerated their standard of living. The actual family villa, located at TraunstraBe 34, Aigen 5026, was large and comfortab1e but not nearly as grand as the mansion depicted in the film. The house was also not their ancestral home, as depicted in the film. The family had previously lived in homes in Zell Am See and Klosterneuburg after being forced to abandon their actual ancestral home in Pola following World War I. Georg moved the family to the Salzburg villa shortly after the death of his first wife, Agathe Whitehead, in 1922.[!_44] In the film, Georg is referred to as "Ca_:g_tain", but his actual family title was "Ritter" (German for "knight"), a b-ereditary knighthood the equivalent of which in the United Kingdom is a baronetcy. Austrian nol:>ility, moreover, was legally abolished in 1919 and the nobiliary particle von was proscribed after World War I, so he was legal1y "Georg Trapp". Both the title and the prepositional nobiliary particle von, however, continued to be widely used unofficially as a matter of courtesy.[i44] Georg was offered a position in the Kriegsmarine, but this occurred before the Anschluss. -

Carrie Underwood Stages Biggest Tour of Career with “The Storyteller Tour – Stories in the Round” Launches with Back to Back Sold out Shows

Information for Release: Carrie Underwood Stages Biggest Tour of Career with “The Storyteller Tour – Stories in the Round” Launches with Back to Back Sold Out Shows Nashville, TN – (February 3, 2016) – Carrie Underwood’s “Storyteller Tour - Stories in the Round” launched on Saturday in Jacksonville, FL, and continued Monday in Atlanta, GA, both to sold-out 360-degree crowds. The tour's 17 semi-trucks and 8 buses rolled into Greensboro, NC for the third show tonight to continue its highly-successful 2016 run. Already fans and critics are raving about her stand-out performances coupled with the dramatic in-the-round stage production. The show "is a no-expense-spared spectacle that highlights her approachable beauty, her roar of a voice and a substantive set of songs that have commanded the charts since her 'American Idol' victory a long decade ago," expressed the Atlanta Journal Constitution. "The in-the-round setup commissioned by Underwood allows for unparalleled vantage points- and even those in the arena's highest peaks could watch one of four oval video screens situated above each side of the stage." And says the Florida Times-Union, "Lasers and swaying spotlights and fireworks and explosions all added to the spectacle. But make no mistake, Underwood was the star of the show." Underwood, known for her vocal prowess and the ability to create stellar performance moments in any realm, concert, television, or recordings, spent much of 2015 working with her team to create her most spectacular concert tour to date. Barry Lather (Rihanna, Mariah Carey, Usher, Michael Jackson) is the tour’s Creative Director and Butch Allen (Metallica, The Eagles, Eric Church, No Doubt) is Production & Lighting Designer. -

F I Biography

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL sound of Music VON TRAPP FAMILY Maria Agatha Franziska Gobertina von Trapp (1914 to 2014) Maria Agatha Franziska Gobertina von Trapp (28 Maria Franziska von Trapp September 1914 - 18 February 2014) was the second-oldest ,. daughter of Georg von Trapp and his first wife, Agathe Whitehead 1 2 f von Trap_p.[ J[ rshe was a member of the Tr~p Family Singers, \-- whose lives inspired the musical and film The Sound of Music. She was portrayed by Heather Menzies as the character "Louisa". t She died at age 99, and was the last surviving sibling portrayed in • l the film.[2 ] j Maria Von Trapp Birth - 28th September 1914 Death - February 2014 - Read more about this here (maria-von-trai:2.1~- Petition for Naturalization, 1948 dies.html) Born Maria Agatha Parents - Agathe Von Trapp and Georg Von Trapp Franziska Gobertina Children - None van Trapp Job - Singer and missionary in Papua New Guinea 28 September 1914 Zell am See, Random Fact - Maria visited her ancestral home in 2008 §alzbu~g, t,ustria- Hungary Maria (born in 1914) lived in Stowe, Vermont, after 27 years of Died 18 February 2014 m issionary work in New Guinea. She went back to Salzburg from (aged 99) time to time. Maria von Trapp died on 28 March 1987, at the age Stowe, Vermont, U.S. of 82 in Morrisville, Vermont. Occupation Singer and Catholic missionary Maria: After spending 30 years as a missionary in New Guinea, died at Children 1 the age of 82 in 1987 and now rests alongside her husband on "their Parent(s) Geo_rg van Trapp property in Vermont. -

DICK's Sporting Goods Announces Opening of CALIA by Carrie Underwood Pop-Up Shops in Three Cities This Holiday Season

PRESS RELEASE DICK'S Sporting Goods Announces Opening Of CALIA By Carrie Underwood Pop-Up Shops In Three Cities This Holiday Season 10/28/2020 PITTSBURGH, Oct. 28, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- DICK'S Sporting Goods (NYSE: DKS), the largest U.S.-based, omni- channel sporting goods retailer, announced the opening of three temporary pop-up-shop locations for CALIA by Carrie Underwood, a tness and lifestyle brand created ve years ago in partnership with Grammy®-award winning superstar, Carrie Underwood. The line has become one of the Company's top-selling women's brands. These temporary stores will provide guests with a unique shopping experience heading into the holiday season. Physical retail shops will open in Austin, TX and Santa Monica, CA. Additionally, one mobile pop-up experience will be available in various locations in and around Nashville, TN. All three retail locations will be open to customers October 28 through December 31. "Like in so many other areas of our business, we see a lot of opportunity to continue to expand CALIA by Carrie Underwood as the athletic apparel category continues to strengthen," said Lauren Hobart, President, DICK'S Sporting Goods. "With our women's business being a strong focus for us this year, and CALIA having such strong success, it felt like the right time to launch these CALIA pop-up locations. We hope to introduce the line to even more women through this new and exciting experience." Since its launch, CALIA by Carrie Underwood has exclusively been available in DICK'S Sporting Goods brick-and- mortar locations and online at calia.com and dicks.com. -

My-Favorite-Songs.Pdf

Maria von Trapp’s Childhood Folk Songs Austrian Folk Songs Translated by Maria von Trapp with Photos and Stories from Her Life The scenic picture on the front cover is the view Maria had each day as a child while she and her siblings lived with their grandmother in Zell am See, Salzburg. The photograph is courtesy of Dietmar Sochor (www.zellamsee-kaprun.com). Most of the members of the von Trapp family were not only endowed with the gift of music but were also talented in the arts. The family’s creativity runs the gamut from sculpting, painting, weaving, illuminated manuscripts and photography to book illustration, as is demonstrated by the drawings in this book by Maria’s niece, Georgia von Trapp. Veritas Press, Lancaster, Pennsylvania ©2008 by Veritas Press 800-922-5082 www.VeritasPress.com ISBN 978-1-932168-73-0 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission from Veritas Press, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior, written permission from Veritas Press. Printed in the United States of America. Dedication To “God from whom all Blessings flow” To our Father, our two Mothers, all of my Sisters and Brothers, and our Teachers Contents A, A, A, the Cat Went on Her Way [Track 1] 2 Blue Jeans [Track 2] 4 Good Old Stork [Track 3] 6 The Cuckoo and the Donkey [Track 4] 8 Hi, Hi, Lullaby [Track 5] 11