Planning Your Coaching : Article for Coach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abdulhadi, Rabab. (2010). ‘Sexualities and the Social Order in Arab and Muslim Communities.’ Islam and Homosexuality. Ed. Samar Habib. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 463–487. Abercrombie, Nicholas, and Brian Longhurst. (1998). Audiences: A Sociological Theory of Performance and Imagination. London: Sage. Abu-Lughod, Lila. (2002). ’Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropolog- ical Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others.’ American Anthropologist 104.3: 783–790. Adams, William Lee. (2010). ‘Jane Fonda, Warrior Princess.’ Time, 25 May, accessed 15 August 2012. http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/ 0,28804,1990719_1990722_1990734,00.html. Addison, Paul. (2010). No Turning Back. The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Ahmed, Sara. (2004). The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Ahmed, Sara. (2010a). The Promise of Happiness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Ahmed, Sara. (2010b). ‘Killing Joy: Feminism and the History of Happiness.’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35.3: 571–594. Ahmed, Sara. (2011). ‘Problematic Proximities: Or Why Critiques of Gay Imperi- alism Matter.’ Feminist Legal Studies 19.2: 119–132. Alieva, Leila. (2006). ‘Azerbaijan’s Frustrating Elections.’ Journal of Democracy 17.2: 147–160. Alieva, Leila. (2009). ‘EU Policies and Sub-Regional Multilateralism in the Caspian Region.’ The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs 44.3: 43–58. Allatson, Paul. (2007). ‘ “Antes cursi que sencilla”: Eurovision Song Contests and the Kitsch-Drive to Euro-Unity.’ Culture, Theory & Critique 48: 1: 87–98. Alyosha. (2010). ‘Sweet People’, online video, accessed 15 April 2012. http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=NT9GFoRbnfc. -

Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., Et Al. Case

Case 15-10952-KJC Doc 712 Filed 08/05/15 Page 1 of 2014 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., et al.1 Case No. 15-10952-CSS Debtor. AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } SCOTT M. EWING, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On July 30, 2015, I caused to be served the: a) Notice of (I) Deadline for Casting Votes to Accept or Reject the Debtors’ Plan of Liquidation, (II) The Hearing to Consider Confirmation of the Combined Plan and Disclosure Statement and (III) Certain Related Matters, (the “Confirmation Hearing Notice”), b) Debtors’ Second Amended and Modified Combined Disclosure Statement and Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Combined Disclosure Statement/Plan”), c) Class 1 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 1 Ballot”), d) Class 4 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 4 Ballot”), e) Class 5 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 5 Ballot”), f) Class 4 Letter from Brown Rudnick LLP, (the “Class 4 Letter”), ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Corinthian Colleges, Inc. -

2020 Earth Sciences Alumni News

ALUMNI NEWS Issue 29 February 2020 for Alumni and Friends Inside: Madeleine Fritz: a Pioneer Female Geologist - pg 17 Field Education: Outer Banks, Trinidad, Turkey - pg 18 Alumni Night & Lab Tours - pg 24 Accolades for Barbara Sherwood Lollar - pg 4 Steve Scott 1941 –2019 1 Table of Contents Message from the Chair Message from the Chair 2 Welcome! It’s a privilege to write to you here again in Focusing on the Future 3 the Newsletter as Chair of our Department. Probably Awards, Honours and Appointments 4 the best part of my job is bridging among long-time Retirements 6 alumni, recent graduates, and our current group of New Staff 7 geoscientists. This year’s Newsletter documents an Departures 7 exceptional breadth of activities and happenings. Joubin-James Distinguished Visitors 8 Personal highlights for me include: joining Barbara Digger Gorman, Past and Present 8 Sherwood Lollar at Rideau Hall to recognize and to Class of 2019 9 celebrate her receipt of the NSERC Herzberg Medal; Student Awards 10 climbing high inside the ignimbrite fairy chimneys Earth Sciences Golf Tournament 12 in Cappadocia with students on our 10-day Donor Acknowledgements 13 adventures in Anatolia; enjoying a beer during the numerous performances of our departmental Faultsettos a cappella group; golfing on a perfect AESRC 13 autumn day with Geology alumni and friends at Nobleton Lakes (apologies to members of my foursome for my various forest/lake/bunker shots and Departmental Research 14 time spent digging potatoes into the Nobleton fairways…). Paleomagnatism Lab Closure 16 Who says the life of an academic Chair is drudgery? Madeleine Fritz 17 We are in the midst of two new hires this year and look forward to two new faculty colleagues: an Assistant Professor in Igneous Petrology/ Field Education 18 High-T Geochemistry and at the Associate/Full Professor level in Applied Geophysics to fill the endowed Teck Chair. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

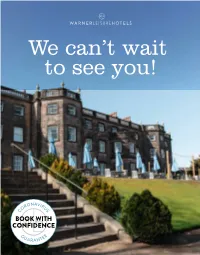

To See You! We Can't Wait

We can’t wait to see you! Britain’s getting booked Full refunds and free changes on all bookings in 2021 Warner’s Coronavirus Guarantee is free on every break in 2021. It gives the flexibility to cancel and receive a full refund, swap dates or change hotels if anything coronavirus-related upsets travel plans. That means holiday protection against illness, tier restrictions, isolation, hotel closure, or simply if you’re feeling unsure. 2 Mountgarret Lounge, Nidd Hall They say the best views come after the hardest climb. Truthfully, it’s been steeper than any of us could have imagined, two steps back for every one forward. But we can see the top now. And I can tell you that it’s never looked so good. We’re keen to make up for the holidays you’ve lost so have been working hard behind closed doors. All your favourites are back – what would Warner be without those amazing menus and shows – but we’re also injecting everything with a whole new lease of life. Disco Inferno The support we give the British entertainment industry is stronger than ever with music legends on stage and our unique spin on festivals, at least ten every month. We’re also celebrating the best of British food with brand-new menus and a £3m investment for more restaurants and lounges. Romeo & Juliet on summer lawns, gin festivals, afternoon tea with a twist, cycle trails, wellness retreats, a soul festival. I could go on… It’s exciting, hope you feel it too, especially Popham Suite, Littlecote House Hotel for what’s shaping up to be the year of the staycation. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Commencement Booklet

COMMENCEMENT Class of 2018 MAY 26, 2018 10:00 AM UPPER LAWN Cañada College welcomes you—the Class of 2018—into the ranks of the proud alumni of Cañada College. We also welcome your families and friends to this 50th year celebration, mindful and appreciative of their contribution to your achievement through their support, sacrifice and encouragement. President’s Welcome Welcome to the 50th Commencement Ceremony at Cañada College! Today’s Commencement is a magnificent celebration of our students and the remarkable accomplishments and successes they have achieved. Our graduates, and their loved ones, joining in this celebration today will be hearing inspiring speeches about the bright, promising future that lies ahead for our graduates. Collectively, we share in the excitement of where the next journey may take them. Graduates are also encouraged at the time of Commencement to look back on their experiences – to reflect on what lessons they have learned, who influenced them, and how they have grown and changed. We know that this reflection is important. As students of Cañada College and of life, you’re neither at the beginning or the end of your journey. Instead, you’re somewhere in-between – in the middle you might say. You may not know what lies ahead and you can’t go back and relive the past; you’re simply in the moment. Sometimes it’s challenging to be in the moment; to fully inhabit, explore, and experience every moment – and to be open to what might present itself to you. While in the present moment, you might find that you can be more open to a different point of view; you might be able to quiet all the voices telling you what you should do; you might find the courage to make a difficult choice; you might find some unexpected joy. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

THE BULLETIN the MONTHLY MAGAZINE of the MORGAN THREE-WHEELER CLUB Affiliated to the ACU and MSA: Non-Territorial CLUB WEBSITE

MTWC Group Events in Nov to check with your GO see contact details p 29 6 Nov: Brooklands group meeting at New Inn, Send, Surrey. 6 Nov: East Anglia Group meeting, The Bull Woolpit. 12.00 Noon. 13 Nov: Y.N.D. group meeting, Carbrook hall S9 2FJ. 13 Nov: Far Far South West, Film show, Three Mile Stones, Truro, 19.00hrs. 14 Nov: West Mids group meeting, Fruiterers Arms, Ombersley, 20.00hrs. 14 Nov: North West Group, Lunch at The Smoker, A556, Plumley, WA16 0TY. 14 Nov: Far Far South West Group, Drive it run from London Inn Summercourt to St Breward for lunch. Start 10.00hrs. 15 Nov: Lancs Lakes Sub-group, Anniversary/pre-Christmas meal. Royal Oak, Garstang 19.00hrs. 20 Nov: Far South West group meeting, The Huntsman. 20 Nov: East Anglia Group meeting, Hare Arms, Stow Bardulph, 20.00hrs. 21 Nov: East Mids Group meeting, Royal Oak, Brandon. 20.00hrs. 22 Nov: South West Group meeting, The Crossways Inn, West Huntspill A38. 27 Nov: Y.N.D. Group meetingReindeer Inn, WR4 4RL. 28 Nov: West Mids Group meeting, Clent Club, 20.00hrs. 30 Nov: Oxford Sub-group meeting, The Star Inn , Stanton St Joseph, 20.00hrs. 30 Nov: North West group meeting, The Whipping Stocks, Over Peover, 20.00hrs. Very important announcement The Night Trial will now take place on the night of Saturday 1st and Sunday 2nd December and NOT as previously stated the 10th & 11th November. This is because the ACU do not allow competitions on Remembrance Sunday! NIGHT TRIAL 1st & 2nd DECEMBER Contents. -

The African-American Emigration Movement in Georgia During Reconstruction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Summer 6-20-2011 The African-American Emigration Movement in Georgia during Reconstruction Falechiondro Karcheik Sims-Alvarado Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sims-Alvarado, Falechiondro Karcheik, "The African-American Emigration Movement in Georgia during Reconstruction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/29 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN EMIGRATION MOVEMENT IN GEORGIA DURING RECONSTRUCTION by FALECHIONDRO KARCHEIK SIMS-ALVARADO Under the Direction of Hugh Hudson ABSTRACT This dissertation is a narrative history about nearly 800 newly freed black Georgians who sought freedom beyond the borders of the Unites States by emigrating to Liberia during the years of 1866 and 1868. This work fulfills three overarching goals. First, I demonstrate that during the wake of Reconstruction, newly freed persons’ interest in returning to Africa did not die with the Civil War. Second, I identify and analyze the motivations of blacks seeking autonomy in Africa. Third, I tell the stories and challenges of those black Georgians who chose emigration as the means to civil and political freedom in the face of white opposition. In understanding the motives of black Georgians who emigrated to Liberia, I analyze correspondence from black and white Georgians and the white leaders of the American Colonization Society and letters from Liberia settlers to black friends and families in the Unites States. -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People..