The Quality of First Amendment Speech Randall P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Law Mnemonics

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW MNEMONICS 1) PEG a violation of the Establishment Clause: P – The state statute or activity must have a primarily secular PURPOSE as opposed to the purpose of advancing or inhibiting religion E – The law’s primary or inevitable EFFECT must neither disapprove of nor endorse religion AND G – The law or conduct can’t foster excessive GOVERNMENTAL religious entanglement 2) A content-neutral regulation must be a reasonable SON of the First Amendment: S – The restriction must be justified by a SIGNIFICANT governmental interest O – The regulation must leave OPEN ample alternative channels of communication AND N – The regulation must be NARROWLY tailored to further the government’s goal, but doesn’t have to be least restrictive means of doing so 3) All commercial speech restrictions with STAN are valid: S – Government must have a SUBSTANTIAL INTEREST to restrict the speech T – Advertisements must be TRUTHFUL and concern lawful products and services A – Governmental restrictions must directly and materially ADVANCE the government’s “substantial interest” in enacting the law (and there must be “reasonable fit” between the state’s goal and means used to achieve that goal) N – The regulation must be NARROWLY-DRAWN and must not be more extensive than necessary to achieve the government’s substantial interest 4) The statute’s primary purpose must be a secular (non-religious) purpose, as opposed to a DOE purpose of Disapproving Or Endorsing religion 5) SLAP POP’S PAW is simply obscene, and is not constitutionally protected: SLAP – -

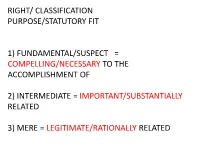

Right/ Classification Purpose/Statutory Fit

RIGHT/ CLASSIFICATION PURPOSE/STATUTORY FIT 1) FUNDAMENTAL/SUSPECT = COMPELLING/NECESSARY TO THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF 2) INTERMEDIATE = IMPORTANT/SUBSTANTIALLY RELATED 3) MERE = LEGITIMATE/RATIONALLY RELATED CHARLOTTESVILLE, PORTLAND - ALT RIGHT MARCHING IN REVERSE (LIBERAL COLLEGE TOWNS, JEWISH CITY) FACT SPECIFIC – WHAT SAID, WHERE 1. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH STREETS OR SIDEWALKS (COSTS AND LIABILITY) ? 2. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PUBLIC UNIVERSITY ? 3. RIGHT TO MARCH THROUGH CAMPUS OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITY ? ACTUALLY PRACTICE THIS – EVEN IN SMALL TOWNS. BASIC FIRST AMENDMENT FOUNDATION: 1) CONGRESS/STATE (14 AMENDMENT) CAN VIOLATE FIRST AMENDMENT (NOT EMPLOYER – NFL - KAPERNICK) 2) PRIVATE = TORT, NOT FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION 3) BEWARE IF NON SPEECH ELEMENT – CAN BE PUNISHED EG SPRAY PAINT ANTI-SEMETIC ON SCHOOL WALLS 4) MANY CRAZY LAWS AND ORDINANCES IN EXISTENCE. USSC DOES NOT REPEAL – STILL ON BOOKS 5) MANY PRACTICES VIOLATING THE FIRST AMENDMENT AREN’T CHALLENGED (EG PUBLIC PROFANITY ARREST) BASIC – WHAT IS THE MEANING OF FIRST AMENDMENT ? ASSUME NO KNOWLEDGE OF CASE LAW. EVERYONE IS A FIRST AMENDMENT LIBERAL. 1) MUSIC ? RHAPSODY IN THE RAIN (1966). 2) PROCREATE, INTERCOURSE, FORNICATE, FREAKING 3) GENOCIDE ? HATE SPEECH ? INTERNET TROLLS ? 4) SNOWDEN AND THE HACKIVISTS 5) TRY TO BRIBE JUDGE ? 6) WHEN CAN GOV’T ARREST ? BIG DATA AND PROBLEMS USA TODAY - AUGUST 19, 2019 1. CONNECTICUT – TRYING TO BUY HIGH CAPACITY RIFLE MAGAZINES ON LINE AND FACEBOOK “AN INTEREST IN COMMITTING A MASS SHOOTING”. COPS FOUND 2 GUNS, AMMUNITION, BODY ARMOR AND OTHER EQUIP. 2. FLORIDA – MULTIPLE TEXTS WITH PLANS TO COMMIT A MASS SHOOTING. “LARGE CROWD FROM 3 MILES AWAY. 100 KILLS WOULD BE NICE. -

Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 31 | Issue 5 Article 5 1-1980 Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California Robert C. Black Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert C. Black, Attorney Discipline for Offensive Personality in California, 31 Hastings L.J. 1097 (1980). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol31/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Attorney Discipline for "Offensive Personality" in California By ROBERT C. BLACK* According to one of the most venerable and dubious of legal fictions, everyone is presumed to know the law.' Fortunately for our peace of mind, most of us know little of the myriad laws we are obliged to obey. Although they never discuss the subject, lawyers are well aware that any serious attempt by the authorities to enforce all the en- actments which technically are in force would sabotage the social or- der.2 Despite the strictures of legal ethics,3 insofar as lawyers provide guidance for the practical conduct of real life they necessarily counte- nance and even commit nominal infractions routinely. With law, as with everything else, there can be too much of a good thing; and if there is anything we have too much of, it is law: "There is not much danger of erring upon the side of too little law. -

US Constitution First Amendment: an Overview

US Constitution first amendment: an overview The First Amendment of the United States Constitution protects the right to freedom of religion and freedom of expression from government interference. See U.S. Const. amend. I. Freedom of expression consists of the rights to freedom of speech, press, assembly and to petition the government for a redress of grievances, and the implied rights of association and belief. The Supreme Court interprets the extent of the protection afforded to these rights. The First Amendment has been interpreted by the Court as applying to the entire federal government even though it is only expressly applicable to Congress. Furthermore, the Court has interpreted, the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as protecting the rights in the First Amendment from interference by state governments. See U.S. Const. amend. XIV. Two clauses in the First Amendment guarantee freedom of religion. The establishment clause prohibits the government from passing legislation to establish an official religion or preferring one religion over another. It enforces the "separation of church and state." Some governmental activity related to religion has been declared constitutional by the Supreme Court. For example, providing bus transportation for parochial school students and the enforcement of "blue laws" is not prohibited. The free exercise clause prohibits the government, in most instances, from interfering with a person's practice of their religion. The most basic component of freedom of expression is the right of freedom of speech. The right to freedom of speech allows individuals to express themselves without interference or constraint by the government. The Supreme Court requires the government to provide substantial justification for the interference with the right of free speech where it attempts to regulate the content of the speech. -

Matal V. Tam & the Right to Own Disparaging Words

WHAT’S IN A NAME?: MATAL V. TAM & THE RIGHT TO OWN DISPARAGING WORDS I. INTRODUCTION In June 2017, the Supreme Court decided Matal v. Tam,1 a rare case in which intellectual property and First Amendment law collided.2 The principal question was whether the Lanham Act’s (“the Act”) Disparagement Clause was constitutional.3 While the Court had declined to answer this question with previous plaintiffs, such as the Washington Redskins (“the Redskins”), the Court granted certiorari to Simon Tam (“Tam”) and his Asian-American bandmates to decide whether the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) had wrongly denied trademark registration for their band name: The Slants.4 Tam and his bandmates (collectively “The Slants”) are more sympathetic plaintiffs than the Washington Redskins: they are Asian-Americans reclaiming an outdated term derogatory to Asian-Americans.5 The Redskins, on the other hand, operate under a long-reviled racist term for Native Americans, and at best, a slim minority of their members is Native American.6 The Slants won their Supreme Court case, but the Court left unresolved the next question, which is what this decision means for less-than-sympathetic parties like the Redskins.7 This paper will explore what rights individuals and organizations have in owning derogatory terminology. Part II provides the background of trademark registration criteria and benefits, a summary of the process to appeal rejected trademarks, an introduction to the Act and Disparagement Clause, and a brief overview of First Amendment law. Part III provides a history 1 137 S. Ct. 1744 (2017). 2 See generally id. -

First Amendment Tests from the Burger Court: Will They Be Flipped?

FIRST AMENDMENT TESTS FROM THE BURGER COURT: WILL THEY BE FLIPPED? David L. Hudson, Jr. † and Emily H. Harvey †† I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 52 II. THE LEMON TEST ..................................................................... 53 III. THE MILLER TEST .................................................................... 58 IV. THE CENTRAL HUDSON TEST ..................................................... 63 V. CONCLUSION ........................................................................... 66 I. INTRODUCTION When scholars speak of the Burger Court, they often mention the curtailing of individual rights in the criminal justice arena, 1 federalism decisions, 2 its “rootless activism,” 3 a failure in equal † David L. Hudson, Jr., is a Justice Robert H. Jackson Legal Fellow with the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) and the Newseum Institute First Amendment Fellow. He teaches at the Nashville School of Law and Vanderbilt Law School. He would like to thank his co-author Emily Harvey, the student editors of the Mitchell Hamline Law Review , and Azhar Majeed of FIRE. †† Emily H. Harvey is the senior judicial law clerk for the Hon. Frank G. Clement, Jr., of the Tennessee Court of Appeals. 1. See Yale Kamisar, The Warren Court and Criminal Justice: A Quarter-Century Retrospective , 31 TULSA L.J. 1, 14, 44 (1995); Steven D. Clymer, Note, Warrantless Vehicle Searches and the Fourth Amendment: The Burger Court Attacks the Exclusionary Rule , 68 CORNELL L. REV . 105, 129, 141, 144–45 (1982). 2. See David Scott Louk, Note, Repairing the Irreparable: Revisiting the Federalism Decisions of the Burger Court , 125 YALE L.J. 682, 686–87, 694, 710, 724–25 (2016); Lea Brilmayer & Ronald D. Lee, State Sovereignty and the Two Faces of Federalism: A Comparative Study of Federal Jurisdiction and the Conflict of Laws , 60 NOTRE DAME L. -

Courtside Paul M

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Popular Media Faculty and Deans 2005 Courtside Paul M. Smith Katherine A. Fallow Daniel Mach Aaron-Andrew P. Bruhl William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Smith, Paul M.; Fallow, Katherine A.; Mach, Daniel; and Bruhl, Aaron-Andrew P., "Courtside" (2005). Popular Media. 412. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media/412 Copyright c 2005 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media COURTSIDE BY PAUL M. SMITH, KATHERINE A. FALLOW, DANIEL MACH, AND AARON A. BRUHL As sometimes happens, the most dramatic efforts. Shortly thereafter, columnist a libertarian advocacy group, and the development at the Supreme Court for Robert Novak wrote a piece revealing attorneys general of thirty-four states and First Amendment lawyers in recent that "senior administration officials" the District of Columbia. The brief of the weeks probably was the denial of review told him that Wilson had been sent to attorneys general in support of certiorari in reporter's privilege cases arising Iraq on the recommendation of his wife, was particularly striking in arguing that from the disclosure of the identity of Valerie Plame, a CIA "operative." Critics the absence of a federal privilege frustrat Valerie Plame as a CIA operative-an of the Bush administration alleged that ed state policies because all of those action that resulted in the jailing of one White House officials leaked the infor states (in addition to almost every other prominent journalist. -

Limiting Political Contributions After Mccutcheon, Citizens United, and Speechnow Albert W

Florida Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 2 Article 1 January 2016 Limiting Political Contributions After McCutcheon, Citizens United, and SpeechNow Albert W. Alschuler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Albert W. Alschuler, Limiting Political Contributions After McCutcheon, Citizens United, and SpeechNow, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 389 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol67/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alschuler: Limiting Political Contributions After <i> McCutcheon</i>, <i>Cit LIMITING POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS AFTER MCCUTCHEON, CITIZENS UNITED, AND SPEECHNOW Albert W. Alschuler* Abstract There was something unreal about the opinions in McCutcheon v. FEC. These opinions examined a series of strategies for circumventing the limits on contributions to candidates imposed by federal election law, but they failed to notice that the limits were no longer breathing. The D.C. Circuit’s decision in SpeechNow.org v. FEC had created a far easier way to evade the limits than any of those the Supreme Court discussed. SpeechNow held all limits on contributions to super PACs unconstitutional. This Article argues that the D.C. Circuit erred; Citizens United v. FEC did not require unleashing super PAC contributions. The Article also considers what can be said for and against a bumper sticker’s declarations that “MONEY IS NOT SPEECH!” and “CORPORATIONS ARE NOT PEOPLE!” It proposes a framework for evaluating the constitutionality of campaign-finance regulations that differs from the one currently employed by the Supreme Court. -

Taking First Amendment Procedure Seriously: an Analysis of Process in Libel Litigation

Taking First Amendment Procedure Seriously: An Analysis of Process in Libel Litigation SUSAN M. GiLLEs* This Article addresses a critical problem in libel law: when should established procedural rules be altered to protect free speech. The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that special or modified proceduralrules are necessary to safeguard First Amendment interests. Yet, as Professor Gilles demonstrates, the Court has failed to articulate a rationalefor determining what proceduralrules should apply in libel cases. Instead, it has proceeded on a case by case basis, granting and denying procedural breaks without explanation. While the process created by the Court seems highly effective at safeguardingfree speech interests, a second glance reveals that jury error is rampant, with reversal, remand, and damage reduction rates running at over 70%. Professor Gilles argues that the Court has created a procedural quagmire which serves neitherplaintiffs, defendants, nor the FirstAmendment. Professor Gilles then reexamines what we mean by First Amendment process. She contends that the problems of the current system stem from the Court's preoccupation with accuracy and its failure to recognize the equally vital goals of speed and efficiency. Professor Gilles argues that ifthe Court adopted a more balancedapproach, giving consistent consideration of all three goals, it could rationalize and improve the process for deciding libel cases. This Article concludes by offering a number of specific reforms toward that end. "[It is important to ensure not only that the substantiveFirst Amendment standardsare sound, but also that they are applied through reliable procedures.,,1 I. INTRODUCTION I have often imagined a debate between Justices Brennan and Black over the case of New York Times Co. -

Free Speech for Lawyers W

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 28 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 2001 1-1-2001 Free Speech for Lawyers W. Bradley Wendel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation W. Bradley Wendel, Free Speech for Lawyers, 28 Hastings Const. L.Q. 305 (2001). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech for Lawyers BYW. BRADLEY WENDEL* L Introduction One of the most important unanswered questions in legal ethics is how the constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression ought to apply to the speech of attorneys acting in their official capacity. The Supreme Court has addressed numerous First Amendment issues in- volving lawyers,' of course, but in all of them has declined to consider directly the central conceptual issue of whether lawyers possess di- minished free expression rights, as compared with ordinary, non- lawyer citizens. Despite its assiduous attempt to avoid this question, the Court's hand may soon be forced. Free speech issues are prolif- erating in the state and lower federal courts, and the results betoken doctrinal incoherence. The leader of a white supremacist "church" in * Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University School of Law. LL.M. 1998 Columbia Law School, J.D. 1994 Duke Law School, B.A. -

MORSE V. FREDERICK

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2006 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus MORSE ET AL. v. FREDERICK CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 06–278. Argued March 19, 2007—Decided June 25, 2007 At a school-sanctioned and school-supervised event, petitioner Morse, the high school principal, saw students unfurl a banner stating “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS,” which she regarded as promoting illegal drug use. Consistent with established school policy prohibiting such messages at school events, Morse directed the students to take down the banner. When one of the students who had brought the banner to the event—respondent Frederick—refused, Morse confiscated the banner and later suspended him. The school superintendent upheld the suspension, explaining, inter alia, that Frederick was disciplined because his banner appeared to advocate illegal drug use in violation of school policy. Petitioner school board also upheld the suspension. Frederick filed suit under 42 U. S. C. §1983, alleging that the school board and Morse had violated his First Amendment rights. The Dis- trict Court granted petitioners summary judgment, ruling that they were entitled to qualified immunity and that they had not infringed Frederick’s speech rights. -

Brief Amici Curiae of Goldwater Institute

No. 19-988 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- LIVING ESSENTIALS, LLC; INNOVATION VENTURES, LLC, Petitioners, v. STATE OF WASHINGTON, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The Washington Court Of Appeals, Division One --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE GOLDWATER INSTITUTE, CATO INSTITUTE, AND REASON FOUNDATION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- ILYA SHAPIRO JACOB HUEBERT* TREVOR BURRUS SCHARF-NORTON CENTER CATO INSTITUTE FOR CONSTITUTIONAL 1000 Mass. Ave. NW LITIGATION AT THE Washington, DC 20001 GOLDWATER INSTITUTE (202) 842-0200 500 E. Coronado Rd. [email protected] Phoenix, AZ 85004 (602) 462-5000 MANUEL S. KLAUSNER litigation@ LAW OFFICE OF goldwaterinstitute.org MANUEL S. KLAUSNER *Counsel of Record 333 S. Grand Ave., Ste. 4200 Los Angeles, CA 90071 (213) 617-0414 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Under the “prior substantiation” doctrine, a busi- ness may be held liable for making a factual claim if a court concludes the business lacked adequate