Syllabus, Ezekiel and Daniel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Testament Theology

1 Seminar in Biblical Literature: Ezekiel (BIB 495) Point Loma Nazarene University Fall 2015 Professor: Dr. Brad E. Kelle Monday 2:45-5:30pm Office: Smee Hall (619)849-2314 [email protected] Office Hours: posted on door “Ah Lord Yahweh! They are saying of me, ‘Is he not always talking metaphors?’” (Ezek 20:49 [Eng.]). “There is much in this book which is very mysterious, especially in the beginning and latter end of it” –John Wesley (Explanatory Notes, 2281). COURSE DESCRIPTION (see also PLNU catalogue) This course engages the student in the study of the book of Ezekiel in English translation. Primary attention will be given to reading Ezekiel from various interpretive angles, examining the book section by section and considering major themes and motifs that run through the book, as well as specific exegetical issues. Instruction will be based upon English translations, although students who have studied Hebrew will be encouraged to make use of their skills. COURSE FOCUS The focus of this course is to provide a broad exegetical engagement with the book of Ezekiel. This engagement will involve study of the phenomenon of prophecy, the general background of Ezekiel the prophet and book, the literary and theological dynamics of the book, and the major interpretive issues in the study of Ezekiel. The aim of the course is to work specifically with the biblical text in light of the historical, social, and religious situation of the sixth century B.C.E. It will also explore, however, the meaning and significance of the literature within Christian proclamation as well as the diverse literary, theological, and methodological issues connected with these texts. -

(Leviticus 10:6): on Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible

1 “Do not bare your heads and do not rend your clothes” (Leviticus 10:6): On Mourning and Refraining from Mourning in the Bible Yael Shemesh, Bar Ilan University Many agree today that objective research devoid of a personal dimension is a chimera. As noted by Fewell (1987:77), the very choice of a research topic is influenced by subjective factors. Until October 2008, mourning in the Bible and the ways in which people deal with bereavement had never been one of my particular fields of interest and my various plans for scholarly research did not include that topic. Then, on October 4, 2008, the Sabbath of Penitence (the Sabbath before the Day of Atonement), my beloved father succumbed to cancer. When we returned home after the funeral, close family friends brought us the first meal that we mourners ate in our new status, in accordance with Jewish custom, as my mother, my three brothers, my father’s sisters, and I began “sitting shivah”—observing the week of mourning and receiving the comforters who visited my parent’s house. The shivah for my father’s death was abbreviated to only three full days, rather than the customary week, also in keeping with custom, because Yom Kippur, which fell only four days after my father’s death, truncated the initial period of mourning. Before my bereavement I had always imagined that sitting shivah and conversing with those who came to console me, when I was so deep in my grief, would be more than I could bear emotionally and thought that I would prefer for people to leave me alone, alone with my pain. -

Sovereign God, Daniel 4:28-37 What Is God Really Like #5

Sovereign God, Daniel 4:28-37 What is God Really Like #5 ✦Intro: Modern research has show that Nebuchadnezzer was the greatest monarch that Babylon or perhaps the East generally, has ever produced. He must have possessed an enormous command of human labor for nine tenths of Babylon itself and 19/20ths of all other ruins that in almost countless profusion cover the land, are composed of bricks stamped with his name. He appears to have built or restored almost every city and temple in the whole country. His inscriptions give an elaborate account of the immense works which he constructed in and about Babylon itself, abundantly illustration the boast, “Is not this great Babylon which I have built?” (Rawlinson, Historical Illustrations) Many inscriptions in cuneiform have been found, which describe the city. There is also an account by the Greek historian Herodotus, who visited the city of Babylon in about 460 BC. Here are some interesting things he recorded: ✦-The city was laid out in the form of a square, 14 miles on each side, and of enormous magnitude ✦-The brick wall was 56 miles long, 300 feet high, 25 feet thick with another wall 75 feet behind the first wall, and the wall extended 35 feet below the ground ✦-250 towers that were 450 feet high 1 Sovereign God, Daniel 4:28-37 What is God Really Like #5 ✦-A wide and deep moat that encircled the city ✦-The Euphrates River also flowed through the middle of the city. Ferry boats and a 1/2 mi. long bridge with drawbridges closed at night ✦Golden image of Baal and the Golden Table (both weighing over 50,000 lbs of solid gold.) ✦-2 golden lions, a solid gold human figure (18 feet high) ✦Nebuchadnezzar was our kinda guy. -

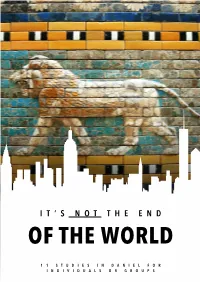

Daniel for Individuals Or Groups Start of Old Testament Period Creation

IT’S NOT THE END OF THE WORLD 11 STUDIES IN DANIEL FOR INDIVIDUALS OR GROUPS START OF OLD TESTAMENT PERIOD CREATION ADAM & EVE THE FALL Please do not republish republish not do Please NOAH THE FLOOD | BABEL ABRAHAM (c. 2165-1990) visualunit.me ISAAC (c. 2065-1885) | JACOB (c. 2000-1860) JOSEPH (c. 1910-1800) MOSES (c. 1525 - 1405) THE EXODUS (c. 1450) JOSHUA THE LAW THE PROMISED LAND BIBLE TIMELINE © Mark Barry 2008 All use. personal for copy to free feel but permission, without approximate. are dates THE JUDGES (c. 1380-1050) SAUL (reign 1050-1010) DAVID (reign 1010-970) SOLOMON (reign 970-930) THE TEMPLE (966) REHOBOAM (reign 930-913) JEROBOAM I (reign 930-909) SOUTHERN KINGDOM: JUDAH NORTHERN KINGDOM: ISRAEL ELIJAH (875-848) ISAIAH (740-681) ELISHA (848-797) MICAH (750-686) JONAH (785-775) KINGDOM HOSEA (750-715) JEREMIAH (626-585) DIVIDED OBADIAH (605-585) (922) EZEKIEL (593-571) 1st DEPORTATION (597) EXILE TO DANIEL (605-530) ASSYRIA 2nd DEPORTATION (586) JERUSALEM DESTROYED (722) EXILE TO 1st RETURN (538) BABYLON under ZERUBBABEL ZECHARIAH (520-480) (597-432) 2nd RETURN (458) under EZRA MALACHI (440-430) LAST RETURN (432) under NEHEMIAH END OF OLD TESTAMENT PERIOD BETWEEN THE TESTAMENTS (432-5 BC) START OF NEW TESTAMENT PERIOD JESUS BORN (5 BC) JESUS BEGINS PUBLIC MINISTRY (26 AD) JOHN THE BAPTIST JESUS’ DEATH, RESURRECTION + ASCENSION (30) PENTECOST (30) PAUL CONVERTED (35) 1st MISSIONARY JOURNEY (46-48) JAMES MARTYRED + PETER IMPRISONED (44) 2nd MISSIONARY JOURNEY (50-52) JERUSALEM COUNCIL (49-50) 3rd MISSIONARY JOURNEY (53-57) -

The Levite's Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander

Vetus Testamentum 68 (2018) 519-539 Vetus Testamentum brill.com/vt The Levite’s Concubine (Judg 19:2) and the Tradition of Sexual Slander in the Hebrew Bible: How the Nature of Her Departure Illustrates a Tradition’s Tendency Jason Bembry Emmanuel Christian Seminary at Milligan College [email protected] Abstract In explaining a text-critical problem in Judges 19:2 this paper demonstrates that MT attempts to ameliorate the horrific rape and murder of an innocent person by sexual slander, a feature also seen in Balaam and Jezebel. Although Balaam and Jezebel are condemned in the biblical traditions, it is clear that negative portrayals of each have been augmented by later tradents. Although initially good, Balaam is blamed by late biblical tradents (Num 31:16) for the sin at Baal Peor (Numbers 25), where “the people begin to play the harlot with the daughters of Moab.” Jezebel is condemned for sorcery and harlotry in 2 Kgs 9:22, although no other text depicts her harlotry. The concubine, like Balaam and Jezebel, dies at the hands of Israelites, demonstrating a clear pattern among the late tradents of the Hebrew Bible who seek to justify the deaths of these characters at the hands of fellow Israelites. Keywords judges – text – criticism – sexual slander – Septuagint – Josephus The brutal rape and murder of the Levite’s concubine in Judges 19 is among the most horrible stories recorded in the Hebrew Bible. The biblical account, early translations of the story, and the early interpretive tradition raise a number of questions about some details of this tragic tale. -

Ezekiel 16:1-14 Commentary

Ezekiel 16:1-14 Commentary PREVIOUS NEXT Ezekiel 16:1 Then the word of the LORD came to me, saying, (NASB: Lockman) AN OUTLINE OF EZEKIEL 16 An Allegory of Unfaithful Jerusalem (NIV) God's Unfaithful Bride (NET) God's Grace to Unfaithful Jerusalem (NASB) Jerusalem the Unfaithful (Good News Bible) Ezekiel 16:1-14 The Lord's Loving kindnesses to Jerusalem Ezekiel 16:15-34 Unfaithful Jerusalem's Harlotry Ezekiel 16:35-50 God's Judgment on Jerusalem Ezekiel 16:51-63 Sodom & Samaria Will be Restored (53-58) (GNB) Jerusalem Will Be Ashamed (53-58) (CEV) Covenant that Lasts Forever (59-63) (GNB) Warren Wiersbe - This long chapter contains some of the most vivid language found anywhere in Scripture. It is addressed to the city of Jerusalem but refers to the entire nation. The chapter traces the spiritual history of the Jews from “birth” (God’s call of Abraham) through “marriage” (God’s covenant with the people), and up to their “spiritual prostitution” (idolatry) and the sad consequences that followed (ruin and exile). The Lord takes His “wife” to court and bears witness of her unfaithfulness to Him. At the same time, the Lord is replying to the complaints of the people that He had not kept His promises when He allowed the Babylonians to invade the land. God did keep His covenant; it was Israel who broke her marriage vow and also broke the heart of her Lord and invited His chastening (Ezek. 6:9). But as we read the chapter, we must see not only the dark background of Israel’s wickedness but also the bright light of God’s love and grace. -

THRU the BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel

THRU THE BIBLE EXPOSITION Ezekiel: Effective Ministry To The Spiritually Rebellious Part XXXIII: Illustrating Israel's Great Pain From God's Discipline (Ezekiel 24:15-27) I. Introduction A. When God disciplines man for sin, His discipline is very painful that it might produce the desired repentance. B. Ezekiel 24:15-27 provides an illustration of this truth, and we view this passage for our insight (as follows): II. Illustrating Israel's Great Pain From God's Discipline, Ezekiel 24:15-27. A. God made Ezekiel a moving illustration of the painful shock his fellow Hebrew captives would experience at the fall of Jerusalem in God's judgment, the destruction of their beloved temple and children, Ezek. 24:15-24: 1. After God's prophet in Ezekiel 24:1-14 announced that the Babylonian army had begun its siege of Jerusalem, the Lord told Ezekiel that He was going to take the delight of his eyes, Ezekiel's wife, away from him in death with a "blow," that is, to take her life very suddenly, Ezekiel 24:15-16a NIV. 2. Regardless of the intense shock of such event, Ezekiel was not to mourn or weep, not to let tears run from his eyes, but to sigh silently, to perform no public mourning act for the dead, Ezek. 24:16b-17a. Rather, he was to bind on his turban, put on his sandals, not cover the lower part of his face nor eat any food, highly unusual behavior for a man who had just tragically, suddenly lost his beloved wife, Ezekiel 24:17b NIV. -

Ezekiel 14:9 Ezekiel Speaks of Those Who Abuse Their Prophetic Office

1 Ted Kirnbauer God Deceives the Prophets In Ezekiel 14:9 Ezekiel speaks of those who abuse their prophetic office. There he states that the false prophets speak deceptive words because God has deceived them. This of course generates a lot of questions: If God deceives people, how can He be Holy? How do we know that the gospel isn’t a deception of God as well? How can people be responsible for believing a deception if God is the one deceiving them? Answers to these questions would take volumes to explore, but hopefully, the following work by DA Carson and the comments that follow will shed a little light on the subject. Excurses - Sovereignty and Human Responsibility The sovereignty of God and human responsibility is not an easy concept with a simple solution. D.A. Carson does a good job at explaining the relationship between the two. The following comments are taken from A Call To Spiritual Reformation under the chapter entitled “A Sovereign and Personal God.” He says: I shall begin by articulating two truths, both of which are demonstrably taught or exemplified again and again in the Bible: 1. God is absolutely sovereign, but his sovereignty never functions in Scripture to reduce human responsibility. 2. Human beings are responsible creatures – that is, they choose, they believe, they disobey, they respond, and there is moral significance in their choices; but human responsibility never functions in Scripture to diminish God's sovereignty or to make God absolutely contingent. My argument is that both propositions are taught and exemplified in the Bible. -

Daily Bible Study “The Tragedy of Hearing Only” Ezekiel 33:30-33 February 27

Daily Bible Study “The Tragedy of Hearing Only” Ezekiel 33:30-33 February 27 – March 5, 2011 THE LORD’S DAY & MONDAY – This week we take a break from our study of the gospel of Mark as we look back into the old Testament to a passage I pray God would use to speak to you through His Word and by His Spirit and challenge you to evaluate your level of love and service to Him. We will be looking at the prophet Ezekiel with Ezekiel 33:30-33 as our main text. Read this passage of Scripture and ask God to help you evaluate your own level of love and service to Him. The prophet Ezekiel, whose name means "strengthened by God", was a man that God called to speak for Him to His exiled people Israel. Ezekiel was himself a captive exiled from his homeland. There were many "false prophets" who were speaking a positive message to the people, assuring them of a speedy return to Judah. Meanwhile, Ezekiel prophesied the truth, which included the foretelling of the destruction of their beloved Jerusalem. Ezekiel also spoke at length to the future restoration of Israel and the final blessings of the Messianic Kingdom. In Ezekiel chapter 1 we are introduced to the prophet and we read of a vision Ezekiel had of God's glory ( Ezekiel 1:1-28 ) and then God speaks to him in chapter 2 ( Ezekiel 1:28 - 2:9) . Read our text for the week in Ezekiel 33:30-33 : “ As for you, son of man, the children of your people are talking about you beside the walls and in the doors of the houses; and they speak to one another, everyone saying to his brother, ‘Please come and hear what the word is that comes from the LORD.’ So they come to you as people do, they sit before you as My people, and they hear your words, but they do not do them; for with their mouth they show much love, but their hearts pursue their own gain. -

Ezekiel 33. the Turning Point

1 What do you need to know when your world is turned upside down? Ezekiel 33. The Turning Point [33:21] What do you need to know, what should you do, when everything you have taken for granted, the foundational assumptions on which you have built your life, are knocked away in a moment? What do you need to know then? And where can you find a better foundation, a surer foundation on which to build your life? With the uttering of one doom laden sentence “The city has been struck down” Ezekiel 33: 21 In the twelfth year of our exile, in the tenth month, on the fifth day of the month, a fugitive from Jerusalem came to me and said, “The city has Been struck down.” The exiles in Babylon, those to whom Ezekiel has prophesied for the last seven years, have to face the end of everything they have taken for granted and the destruction of their cherished hope. No King of the line of David reigning in Jerusalem – David’s dethroned descendant a prisoner of the pagan Nebuchednezzar no temple. The footstool of the LORD that was meant to make the city inviolable – in ashes, and with it no sacrifice or worship no city of Jerusalem, Zion – the city of God – in ruins, and their families dead or enslaved no land, the land the LORD had promised their fathers, the land to which they longed to return, lost to them forever Where could they now find hope for release and return, for freedom and consolation, for their continuing existence as a people? It is hard to exaggerate the impact of that one sentence. -

Does Ezekiel 28:11–19 Affirm the Fall of Satan in Genesis 1:1–2 As Claimed in the Gap Theory?

VIEWPOINT || JOURNAL OF CREATION 32(3) 2018 Does Ezekiel 28:11–19 affirm the fall of Satan in Genesis 1:1–2 as claimed in the gap theory? Joel Tay and KeeFui Kon The gap theory claims that Ezekiel 28:11–19 and Isaiah 14:12–15 refer to the fall of Satan in the mineral Garden of Eden before Creation Week. This event is said to have occurred in between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2. Gap proponents are intimidated by secular geologists who claim that the earth is billions of years old. By inserting billions of years between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2, gap proponents assume that this allows them to reconcile Scripture with the idea of long ages. This paper demonstrates that the passage in Ezekiel 28 cannot relate to this supposed time gap even if the passage refers to the fall of Satan. If the text is understood as a reference to the fall of Satan, we would still be required to interpret the timing of Satan’s fall as an event that occurred after the sixth day of creation, and the final judgment of Satan is reserved for fire rather than water. We show that the gap theory is an extrabiblical and artificial construct that has been imposed upon the text of Genesis 1:1–2, and that Ezekiel 28 is actually problematic for the gap theory. ap theory claims that there was a previous earth that was 5. God destroyed the earth and everything in it with a Gcreated and then destroyed billions of years ago because worldwide Flood that produced the fossils and rock layers of the rebellion of Lucifer. -

REPENT and LIVE! Ezekiel 18:1-32 Key Verse

REPENT AND LIVE! Ezekiel 18:1-32 Key Verse: 31-32 “Rid yourselves of all the offenses you have committed, and get a new heart and a new spirit. Why will you die, people of Israel? For I take no pleasure in the death of anyone, declares the Sovereign Lord. Repent and live!” Today we’re going to begin a three part study of some highlights from the book of Ezekiel. Why Ezekiel? Ezekiel is alluded to heavily throughout Revelation, because the purpose of the book of Ezekiel was to help God’s people understand and respond to God’s judgment. In Revelation 16 we learned that all judgment is from God alone, and there were two reactions: God’s people say “just and true are your judgments” (Rev 16:5-7) and those belonging to the devil curse God and refuse to repent (16:9,11,21). It seems God has appointed us to study Revelation at this time. How are we responding to God’s judgment on the world? The simple truth is that sickness only exists in the world as a result of sin—my sin. In Ezekiel 18, God convicts his people to stop blaming others, take responsibility for their sin and respond correctly. Ezekiel gives us a unique glimpse into God’s heart and purpose in bringing judgment. It is such a relevant study for us today. According to 1:1-2 Ezekiel was a priest, the son of Buzi, and was among the exiles in Babylon. Because they had broken their marriage covenant with God and forgotten his love and grace, God brought up Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon against them who carried into exile some 10,000 plus of the nobility and middle class first in 605BC—which we can read about in Daniel—and the full exile in 597 BC which included Ezekiel and his wife.