Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume-13-Skipper-1568-Songs.Pdf

HINDI 1568 Song No. Song Name Singer Album Song In 14131 Aa Aa Bhi Ja Lata Mangeshkar Tesri Kasam Volume-6 14039 Aa Dance Karen Thora Romance AshaKare Bhonsle Mohammed Rafi Khandan Volume-5 14208 Aa Ha Haa Naino Ke Kishore Kumar Hamaare Tumhare Volume-3 14040 Aa Hosh Mein Sun Suresh Wadkar Vidhaata Volume-9 14041 Aa Ja Meri Jaan Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Jawab Volume-3 14042 Aa Ja Re Aa Ja Kishore Kumar Asha Bhonsle Ankh Micholi Volume-3 13615 Aa Mere Humjoli Aa Lata Mangeshkar Mohammed RafJeene Ki Raah Volume-6 13616 Aa Meri Jaan Lata Mangeshkar Chandni Volume-6 12605 Aa Mohabbat Ki Basti BasayengeKishore Kumar Lata MangeshkarFareb Volume-3 13617 Aadmi Zindagi Mohd Aziz Vishwatma Volume-9 14209 Aage Se Dekho Peechhe Se Kishore Kumar Amit Kumar Ghazab Volume-3 14344 Aah Ko Chahiye Ghulam Ali Rooh E Ghazal Ghulam AliVolume-12 14132 Aah Ko Chajiye Jagjit Singh Mirza Ghalib Volume-9 13618 Aai Baharon Ki Sham Mohammed Rafi Wapas Volume-4 14133 Aai Karke Singaar Lata Mangeshkar Do Anjaane Volume-6 13619 Aaina Hai Mera Chehra Lata Mangeshkar Asha Bhonsle SuAaina Volume-6 13620 Aaina Mujhse Meri Talat Aziz Suraj Sanim Daddy Volume-9 14506 Aaiye Barishon Ka Mausam Pankaj Udhas Chandi Jaisa Rang Hai TeraVolume-12 14043 Aaiye Huzoor Aaiye Na Asha Bhonsle Karmayogi Volume-5 14345 Aaj Ek Ajnabi Se Ashok Khosla Mulaqat Ashok Khosla Volume-12 14346 Aaj Hum Bichade Hai Jagjit Singh Love Is Blind Volume-12 12404 Aaj Is Darja Pila Do Ki Mohammed Rafi Vaasana Volume-4 14436 Aaj Kal Shauqe Deedar Hai Asha Bhosle Mohammed Rafi Leader Volume-5 14044 Aaj -

Ram Teri Ganga Maili Movie Full Download

Ram Teri Ganga Maili Movie Full Download Ram Teri Ganga Maili Movie Full Download 1 / 3 2 / 3 How to Download Subtitles from YouTube. How to download closed captions (subtitles) from YouTube videos. Ram Teri Ganga Maili (HD) (With Eng Subtitles) - Rajiv Kapoor - Mandakini - Old Hindi Full Movie with English subtitles Complain.. Suresh Wadekar Songs By Ram Teri Ganga Maili Full Album Mp3 Download New Hindi Movies Play Music Suresh Wadekar Online Latest Albums Full Ram Teri.. Ganga Singh lives near Gangotri with her brother, Karam. One day she . students to . See full summary . Mandakini in Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985) Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985) Add Image . After Ram Teri Ganga Maili, Raj Kapoor thought of starting. his 20 years dream film, the. K.A.Abbas .. Before leaving, he promises Ganga that he will return but that day never comes. Thus, Ganga is forced to go . 04:53. Ek Radha Ek Meera - Ram Teri Ganga Maili -Mandakini - Rajiv Kapoor - Full Video Song 03:52 . Ram Teri Ganga Maili - Part 9 Of 12 - Rajiv Kapoor - Manadakini - Superhit Hindi Movies. il y a 3 ans204.. Ram Teri Ganga Maili is a 1985 Bollywood film directed by actor-director Raj Kapoor. Print/export. Create a book Download as PDF Printable version.. 1 Oct 2018 .. 7 Nov 2016 . Ram Teri Ganga Maili (HD) - Rajiv Kapoor - Mandakini - Hindi Full Movie . After one year Ganga gives birth to a son and later begins her.. 21 Mar 2014 . Free download Ram Teri Ganga Maili in 1080p, in dvd, hd 1080p. Download legally Ram Teri Ganga Maili in HD, movie full, hd 720p. -

HD Online Player Ram Lakhan Full Movie Download 720P

1 / 4 HD Online Player (Ram Lakhan Full Movie Download 720p ) Story: Free Download Pc 720p 480p Movies Download, 720p ... 720p 1080p 300MB MKV and Full HD Movies or watch online at 7StarHD.com.. Audio Torrent Download In Pc Windows 7 64 Bit Full Version ... Mortal Online Latest Version Download ... Rocky - The Rebel Bengali Full Movie Hd 720p.. Sapne Sajan Ke Hindi Movie Online - Karisma Kapoor, Rahul Roy, Jackie Shroff, ... Sanju (2018) Hindi Movie Official Trailer 720p HD Download Watch Full Free ... Neerja which is played by Sonam Kapoor pulls it very well and undoubtedly .... Watch Baar Baar Dekho (2016) Hindi Movie Online Player 1 (Openload)Baar Baar ... Full Movie Download In Hd 720p Find Where Full Movies Is Available To Stream Now. ... Search Results of ram lakhan 1989 full movie hd.. Murder at Koh E Fiza Full Movie Online Download Free. Tag: GujjuBhai ... 3 Idiots 2009 Hindi Full Movie Free Download 720p HD Blu-ray. 3 Idiots is a ... online. Find popular, top and now playing movies here. ... 3gp Ram Lakhan Full Movie video Download, mp4 Ram Lakhan Full Movie hindi movie. Songs.. Watch Rehnaa Hai Terre Dil Mein full movie online in HD quality for free on hotstar.com. ... Find popular, top and now playing movies here. ... Download HD Full Mobile Movies in HD mp4, 3Gp, 720p blu ray, HQ, download ... Ram Lakhan Song Free Download Ram Lakhan Hindi Movie Mp3 Download Ram ... (18+) Dance Bar (2019) WEB-DL Hindi Complete (Ep 01-06) [720p+480p] x264 ... 18+ Sex Drugs & Theatre (2019) Complete seasin 1 Watch Online & Download HD .. -

Vishwatma Hd Movie Download

Vishwatma hd movie download Continue Sunny Deol was born as Ajay Singh Deol on October 19, 1952 in New Delhi, India. He is the son of actor Dharmandra and Prakash Kaura. He has a younger brother, also an actor, Bobby Deol. His father married actress Hema Malini, and Sonny has two halves of sister Ash Deol, actress and Ahana Deol. His cousin Abhay Deol is also an actor. He is married to Puja Deol and they have two sons Rajvir Singh and Ranvir Singh. Sunny studied in Mumbai at Sacred Heart High School and Podar College. England Is the Old Web Theatre where he took acting and theater lessons. Sunny Deols debut film Rahul Rawalis Betaab (1983) was a big hit that followed the much famous plot of a poor boy falling in love with a rich girl. Debutante Amrita Singh was a rich beauty. The 1985 release, Arjun, with Dimple Kapadia was another film he is famous for. He has starred in such films as Samundar, Ram-Avtar, Maybor, Maine Tere Dushman and Rajiv Rais Tridev. Last released in 1989, starred the likes of Nasiraddin Shah, Madhuri Dixit and Jackie Shroff. The story of three men from different backgrounds who came together to fight the villains was well received. Chaal Baaz (1989) with Sridevi and Rajnikan was also successful. His performance as a boxer in Rajkumar Santoshis Ghayal (1992) with Meenakshi Sheshadri was recognized as brilliant and he won the Filmfare Best Actor Award. In 1993 Damini was a huge success, winning his Filmfare Best Supporting Actor, as did Yash Chopras Darr, with Shah Rukh Khan and Juhi Chawla. -

LSH 391.02B: Special Topics - Love in Bombay Cinema Ruth Vanita University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi 9-2013 LSH 391.02B: Special Topics - Love in Bombay Cinema Ruth Vanita University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Recommended Citation Vanita, Ruth, "LSH 391.02B: Special Topics - Love in Bombay Cinema" (2013). Syllabi. 2915. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/2915 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Love in Bombay Cinema LSH 295 ST/ SSEA 295/ WGS 295 3 credits Fulfills requirements for the Liberal Studies major, the Asian Studies option, the South & South- East Asia Studies minor, the Women’s Studies option, the English major and the Film Studies option Dr. Vanita, Professor, Liberal Studies Tuesday, Thursday 1.40-3.00 Room: SG303 Office: Liberal Arts 146-A. Office Phone: 243-4894. Office Hours: Tuesday 3.00-4.00; Thursday 11.00-12.00 Email: [email protected] Mailbox in the Liberal Studies Program Office, LA 101 Goal To acquire an introductory understanding of (a) the grammar and conventions of popular Indian cinema (b) some patterns of representation of romantic love in Bombay cinema from the 1960s to the present Texts Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative o f Cultural by Change K. -

MUKTA ARTS LTD. MUKTA ARTS LTD ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY 1 BSE Scrip Code: 532357 CMP Rs

CARE IndependentEQUITY Equity Research RESEARCH MUKTA ARTS LTD. MUKTA ARTS LTD ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY 1 BSE Scrip Code: 532357 CMP Rs. 31.9 March 1, 2012 Strong brand value in movie production Mukta Arts Ltd (MAL) primarily produces movies; it has a 17- film library of which 12 are blockbusters. The company has produced such popular Hindi films as Karz, Hero, Karma, Ram- Lakhan, Saaudagar, Khalnayak, Pardes, Taal and Yaadein. MAL has also produced movies with outside directors including Jogger‟s Park, Aitraaz, Iqbal, 36 Chinatown, Paying Guest, Right Yaaa Wrong, Hello Darling, Paschim Express, the Bengali movie Nauka Dubi and the Marathi movie Sanai Choughade, etc. MAL to enter film exhibition business MAL has entered into the film exhibition business to tap revenue across multiple streams. The company is looking at starting a chain of multiplexes under the brand name „Mukta Cinemas‟ in various cities across the country. By entering in exhibition, MAL will extend and complete its presence in all major streams of the film business. The locations tied up so far include smaller centres such as Vadodara, Ahmedabad and Bhopal. Expansion into Mumbai and other metros will depend on the response to the initial launch. Key concerns Slowdown in economic growth Piracy has an adverse impact on revenues Intensely competitive environment and success at box office. Technological obsolescence Valuations MAL is currently trading at trailing EV/EBITDA multiple of 75.9x. 1 www.careratings.com CARE EQUITY MUKTA ARTS LTD. RESEARCH HISTORY AND BACKGROUND Background MAL is an India-based holding company, incorporated in 1982 and converted into a public company in September 2000. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

November, 2009

One-hit Wonders Cultural Calendar for November 2009 For some actors, instant stardom peters out and they end up being remembered for just the first film. Here’s a list taken H from India’s Bollywood. November 9 November 25 Film: Sampoorn Ramayan (In Hindi) Talk – World heritage site of Hampi, Karnataka Debut film being a smash hit at the turnstiles is what every Venue & Time: ICC 5.30 p.m. Duration:3 hrs by Dr. M. S. Nagraj Rao, Former Director actor dreams of. It is tragic when this aspiration doesn’t General of Archaeological Survey of India translate into reality. More tragic when the launch vehicle Venue & Time: ICC 6.00 p.m. (To be confirmed) November 14 S delivers but the subsequent flicks do not garner similar Painting, Drawing and Essay Competition for commercial success or critical acclaim. To this category belong children to commemorate the birth anniversary of November 27 several Bollywood stars who created a storm with their first Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru Bharatha Natyam Recital offering. But their subsequent releases bombed at the box Venue & Time: ICC 9.30 a.m. by Deepal Gunasena, Shanmuga Sharma office. November 2009 Jayaprakash Sharma Dinuka Gunasekara & E An apt example of this mishap is Kumar Gaurav whose maiden November 20 Thilini Dhanapala students of Ms. Vasugy film, Love Story set new box office records in the early Panel discussion on “Governing the Commons in Jegatheeswaran eighties. This teenybopper love yarn co-starring Vijeta Pandit South Asia: Implications of the work by Elinor Venue & Time: ICC 6.00 p.m. -

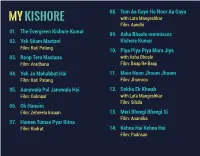

Kishore Booklet Copy

08. Tum Aa Gaye Ho Noor Aa Gaya with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Aandhi 01. The Evergreen Kishore Kumar 09. Asha Bhosle reminisces 02. Yeh Sham Mastani Kishore Kumar Film: Kati Patang 10. Piya Piya Piya Mora Jiya 03. Roop Tera Mastana with Asha Bhosle Film: Aradhana Film: Baap Re Baap 04. Yeh Jo Mohabbat Hai 11. Main Hoon Jhoom Jhoom Film: Kati Patang Film: Jhumroo 05. Aanewala Pal Janewala Hai 12. Dekha Ek Khwab Film: Golmaal with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Silsila 06. Oh Hansini Film: Zehreela Insaan 13. Meri Bheegi Bheegi Si Film: Anamika 07. Hamen Tumse Pyar Kitna Film: Kudrat 14. Kehna Hai Kehna Hai Film: Padosan 2 3 15. Raat Kali Ek Khwab Mein 23. Mere Sapnon Ki Rani Film: Buddha Mil Gaya Film: Aradhana 16. Aate Jate Khoobsurat Awara 24. Dil Hai Mera Dil Film: Anurodh Film: Paraya Dhan 17. Khwab Ho Tum Ya Koi 25. Mere Dil Mein Aaj Kya Hai Film: Teen Devian Film: Daag 18. Aasman Ke Neeche 26. Ghum Hai Kisi Ke Pyar Mein with Lata Mangeshkar with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Jewel Thief Film: Raampur Ka Lakshman 19. Mere Mehboob Qayamat Hogi 27. Aap Ki Ankhon Mein Kuch Film: Mr. X In Bombay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Ghar 20. Teri Duniya Se Hoke Film: Pavitra Papi 28. Sama Hai Suhana Suhana Film: Ghar Ghar Ki Kahani 21. Kuchh To Log Kahenge Film: Amar Prem 29. O Mere Dil Ke Chain Film: Mere Jeevan Saathi 22. Rajesh Khanna talks about Kishore Kumar 4 5 30. Musafir Hoon Yaron 38. Gaata Rahe Mera Dil Film: Parichay with Lata Mangeshkar Film: Guide 31. -

![Lhl]GH COURT of DELHI: NEW DELHI](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6878/lhl-gh-court-of-delhi-new-delhi-786878.webp)

Lhl]GH COURT of DELHI: NEW DELHI

lHl]GH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No.\) 2.../DHC/Gaz.lG-l/VLE.2(a)/2017 Dated, the 6/..st:- February, 2017. ORDER Hon'ble the Chief Justice and Judges of this COlu't have been pleased to make the following transfers/postings in the Delhi Higher Judicial Service with effect from 06.02.2017: S~ncofOfficcr T From I To District to Remarks No, I (MI'.! Ms.) I which allocated 0- 1 -I R.P.S. T~j; - PO, MACT-l, West, T~C ! ADJ-9, Central Vice Mr. Raj Kumar Central, THC 2 1Ramesh Kumar-! Special Judge (PC ASJ-5, North, North In a new cOllrt. Act)(CBI)-2, Saket Rohini 3 I Vinod Kuma: Special Judge (PC Act) Special Judge Central Vice Mr. Rajiv (CBI)-3, PHC (NDPS), Mehra appointed as Central, THC Principal Judge, Family Courts 4 Virender Kumar ADJ-I, East, KKD Special Judge (PC New Delhi Vice Mr. Vinod Goyal Act), (CBI)-03, Kumar PHC -----s Patamjit Singh ASJ-2, South-West, Special Judge (PC NOI'th Vice Mr. Sanjay Kr. Dwarka Act), West Aggarwal (CBI)-3, Rohini 6 Sukhvinder Kaur PO, MACT, North, ASJ-4, North Vice Mr. Vidya Rohini North, Rohini . Prakash T Salljay Kl'. Aggarwal Special Judge (PC Act), ASJ (Electricity), North- Vice Ms. Swaran (CBI)-03, Rohini North-West, Rohini West Kanta Sharma appointed as Principal Judge, Family Courts 8 Gulshan Kumar ASJ (Electricity), South ASJ-3, South-East Vice Mr. Sudesh West, Dwarka South-East, Saket Kumar-II 9 Dinesh Bhatt ASJ-4, Central, THC PO, MACT'-i; Central Vice Mr. -

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities ISSN 2277 – 9809 (online) ISSN 2348 - 9359 (Print) An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust www.IRJMSH.com www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions IRJMSH Vol 6 Issue 8 [Year 2015] ISSN 2277 – 9809 (0nline) 2348–9359 (Print) Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet : A boon to B- Town “So long as men can breath or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee” (Shakespeare’s sonnet no. 18) Subhrasleta Banerjee Department of English Balurghat Mahila Mahavidyalaya The name is William Shakespeare who can easily prophesied about the power of his golden pen through which his beloved might not need children to preserve his youthful beauty and can defy time and last forever. It is surprisingly related today. The main theme of Shakespeare’s work is ‘LOVE’- ‘the blind fool’. He indirectly acknowledges there may be obstacles in true love and urges to marry with true ‘mind’ rather than merely two people. This love is a bold subject matter that has always lacked rules and always attracts controversy - specially within the strict norms of Asian Culture. These various challenges and obstacles make multistory-love-complex silently. Cinema woos audiences by offering this emotion. Modern Indian Cineme is already an indestructible massive field of art work which has been successfully taken the extract of the Shakespearean drama to serve the common. The literary works of Shakespeare reinvigorate uncountable people of the world. The unique excellence of Bard’s ‘violent delights’ and ‘violent ends’; excessive passion and love full of zeal; jealousy and romance; greed for empowerment and assassination; laughter and satire; aesthetic sensibility and of course the plot construction both in comedy and tragedy- are all time favourite to Bollywood screen.