Arts Council Wales – Written Evidence (LBC0292)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operational Plan This Year Reflects an Important Moment of Change

Foreword from the Chair and Chief Executive of the Arts Council of Wales These are challenging times for the publicly funded arts in Wales. This isn’t because people don’t care about them – the public are enjoying and taking part in the arts in large numbers. It isn’t because the work is poor – critical acclaim and international distinction tells us differently. The arts remain vulnerable because continuing economic pressures are forcing uncomfortable choices about which areas of civic life can argue the most persuasive case for support. Fortunately, the Welsh Government recognises and understands the value of arts and creativity. Even in these difficult times, the Government is increasing its funding to the Arts Council in 2017/18 by 3.5%. This vote of confidence in Wales’ artists and arts organisations is as welcome as it’s deserved. But economic austerity continues and this increases our responsibility to ensure that the benefits that the arts offer are available to all. If we want Wales to be fair, prosperous and confident, improving the quality of life of its people in all of the country’s communities, then we must make the choices that enable this to happen – hard choices that will require us to be clear about our priorities. We intend over the coming years to make some important changes – not recklessly or heedlessly, but because we feel that we must try harder to ensure that the benefits of the arts are available more fairly across Wales. It is time to tackle the lack of engagement, amongst those not traditionally able to take part in the arts and in those places where the chance to enjoy the arts is more limited. -

Planning the Destruction of Communities and Their Language Ron Jones

2203-IWALecture2006PaperD(E)JW 3/8/06 12:18 pm Page i Planning the Destruction of Communities and their Language Ron Jones National Eisteddfod Lecture Swansea 2006 i ISBN 1 904773 14 1 2203-IWALecture2006PaperD(E)JW 3/8/06 12:18 pm Page ii Planning the Distruction of Communities and their Language The Author Ron Jones is the founder and Executive Chairman of the Tinopolis group of companies. Tinopolis PLC is amongst the largest independent media companies in the UK. It has more than 400 full-time staff, having grown significantly during 2006 with the acquisition of The Television Corporation PLC. Headquartered in Llanelli the company also has offices in London, Glasgow, Cardiff and Oxford. The company produces over 2,900 broadcast hours of television programming a year. Amongst its better-known programmes are Question Time, the Ashes coverage, Wedi 3 and Wedi 7 and A Very Social Secretary, the drama-documentary on the life and loves of David Blunkett. Ron began his career with Arthur Andersen which he joined on leaving university. After qualifying as a Chartered Accountant he progressed to become a worldwide partner of Arthur Andersen S.A. During his career Ron handled a large number of the firm’s largest and most prestigious clients and worked in a number of countries. Ron was the founder Chairman of Real Radio, the commercial radio licence for south Wales and a joint venture between Tinopolis and the Guardian Media Group. He is a former member of the Council and the Court of Governors of the University of Wales, Swansea. -

Communities and Culture Committee Pwyllgor Cymunedau a Diwylliant

Communities and Culture Committee Pwyllgor Cymunedau a Diwylliant To consultees on the attached list Cardiff Bay Cardiff CF99 1NA July 2010 Dear Colleague, Communities and Culture Committee: inquiry into the ‘accessibility of arts and cultural activities in Wales’ The National Assembly for Wales’ Communities and Culture Committee is calling for evidence for its inquiry into ‘Accessibility of arts and cultural activities in Wales.’ Who are we, and why are we conducting this inquiry? The Communities and Culture Committee is a cross party committee, made up of Members from all 4 political parties represented at the National Assembly for Wales. It is responsible for examining the expenditure, administration and policy of the Welsh Government, and associated public bodies, in relation to Housing, Community Safety, Community Inclusion, the Welsh Language, Sport and Culture. One of the Welsh Government’s main commitments, outlined in ‘One Wales,’ was that ‘high-quality cultural experiences are available to all people, irrespective of where they live or their background.’ As a result of this commitment, many arts and cultural activities receive funding and support, directly or indirectly, from the Welsh Government. We intend to examine whether such investment has been effective in achieving the Welsh Government’s stated objective of widening accessibility to cultural experiences. We are also conscious that the current financial climate will inevitably put pressure on such support, and intend to consider what impact this may have on the Welsh Government’s stated objective of widening accessibility. Ffon / Tel: 029 20 9898736 E-bost / E-mail: sandy mewies.gov.uk We therefore consider that an inquiry into the accessibility of arts and cultural activities to be both timely, and within the remit of our cross-party Committee. -

Communities, Equality and Local Government Committee National Assembly for Wales

INTRODUCTION As Wales‟ national centre for the performing arts we welcome this opportunity to provide evidence to the Committee‟s Inquiry. Attached with this document is a copy of our last Annual Review 2010-2011 and the Annual Review of Free and Participative Activity 2010-2011, both of which highlight how the Centre is extending people‟s horizons, and enriching lives through participation in arts activity. These publications form part of our submitted evidence. In this submission we wish to demonstrate how we deliver against one of our key founding objectives, which forms part of our Strategic Plan 2010-2015, approved by Welsh Government and the Arts Council of Wales, which is to be A place for people of all ages, background and experience to learn about and participate in the arts. This objective also mirrors the strategic priority of the Welsh Government, as outlined in „One Wales,’ which is to ensure that „high-quality cultural experiences are available to all people, irrespective of where they live or their background.‟ It also reflects the ambitions of the Arts Council of Wales through its draft Strategic Equality Plan. From the outset the vision for the Centre was that it was to be more than a place for people who could afford to buy a ticket. As the inscription on the front of the building states so eloquently In these stones horizons sing; in other words it is place where people‟s horizons are extended through the arts, and that means participating and engaging in arts activity as well as watching a performance. -

National Contemporary Art Gallery Wales: Preliminary Feasibility Study

National Contemporary Art Gallery Wales Preliminary Feasibility Study & Options Appraisal July 2018 Client: Museums, Archives and Libraries Division (MALD), Welsh Government Event Authors: Lucie Branczik and Becky Schutt Revision no: 02 Date: July 2018 Event Communications Ltd India House 45 Curlew Street London SE1 2ND +44 (0) 20 7378 9900 [email protected] www.eventcomm.com © Event Communications Ltd 2018 The right of Event Communications Ltd to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988. Front cover: Laura Ford, Cardiff Contemporary Festival Source: Laura Ford Contents Executive Summary 7 Appendices 1. Introduction 17 Appendix 1: Consultation List 138 2. Findings and Opportunities 23 Appendix 2: Site Visits 140 Contemporary Art in Wales 25 Appendix 3: Bibliography 142 Supply: Visual and Applied Arts Ecology 30 Appendix 4: List of Figures 144 Demand: Audiences 51 Appendix 5: The Market 147 Key Contexts 61 Appendix 6: Longlist Options 155 Sector Ambition 86 Appendix 7: Vision and Mission Examples 227 3. Purpose and Vision 91 4. The Options 97 5. Recommendations 103 6. Details of the Model 119 7. Recommended Next Steps 131 “In Britain, whenever people come across something new and exciting, but challenging, there is a tendency for them to run for cover, to want what they know and are comfortable with. To design a great new building takes courage on everyone’s part. I think we have a lot more explaining to do.” Zaha Hadid, 1995 Jonathan Glancey, “A monumental spot of local trouble” (The Independent, Jan 1995) 5 Kelly Best, Installation View. -

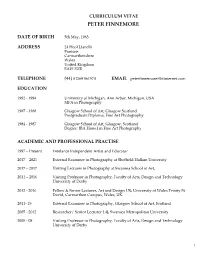

Peter Finnemore

CURRICULUM VITAE PETER FINNEMORE DATE OF BIRTH 5th May, 1963 ADDRESS 24 Heol Llanelli Pontiets Carmarthenshire Wales United Kingdom SA15 5UB TELEPHONE (44) 01269 861570 EMAIL [email protected] EDUCATION 1992 - 1994 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA MFA in Photography 1987 - 1988 Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow Scotland Postgraduate Diploma, Fine Art Photography 1984 - 1987 Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow, Scotland Degree: (BA Hons.) in Fine Art Photography ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL PRACTISE 1997 – Present Freelance Independent Artist and Educator 2017 – 2021 External Examiner in Photography at Sheffield Hallam University 2017 – 2017 Visiting Lecturer in Photography at Swansea School of Art, 2011 – 2016 Visiting Professor in Photography, Faculty of Arts, Design and Technology University of Derby 2012 - 2016 Fellow & Senior Lecturer, Art and Design (.5), University of Wales Trinity St David, Carmarthen Campus, Wales, UK. 2011- 15 External Examiner in Photography, Glasgow School of Art, Scotland 2005 - 2012 Researcher/ Senior Lecturer (.4), Swansea Metropolitan University 2005 - 08 Visiting Professor in Photography, Faculty of Arts, Design and Technology University of Derby 1 2009 -12 Phd External Supervisor (University of Wales Newport) Geraint Davies; Dimensions, Perceptions: Resonances from Durer’s MELENCOLIA I (2012). 2007 - 2009 Welsh Language Fellow of the Welsh National College– Photography (.5) University of Wales, Newport 2000 – 2005 Part Time Lecturer, Photography, Swansea Institute of Higher Education -

Petitions Briefing

The Research Service Research Service # Y Gwasanaeth Ymchwil Research Service Petitions Briefing Y Pwyllgor Deisebau | 3 Hydref, 2017 Petitions Committee | 3 October 2017 Research briefing: To recognize the three hundredth anniversary of Williams Pantycelyn Petition number: P-05-776 Petition title: To recognize the three hundredth anniversary of Williams Pantycelyn Petition topic: We call on the Welsh Government to recognize and commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of the birth of William Williams, Pantycelyn this year (1717-2017). We believe that Williams Pantycelyn has laid the foundations for the modern Wales through all his hymns (over 900), his various literary works (90), and his tireless mission work for the gospel through the whole of Wales for 40 years. The Methodist Reformation of the 18th century, in which Williams played such a key part, led to the establishment of the first national organization in the history of Wales in 400 years, namely the Welsh Calvinistic Methodists (1811). That in turn triggered a series of further educational, social and political reforms which were instrumental in creating the Modern Wales. Pantycelyn therefore is more than just one of the major figures of the faith tradition in Wales. He is one of the major figures of our national story as Welsh people. It is incumbent upon the Welsh Government to recognize his immense contribution to our nation and we call on the Government to arrange an appropriate celebration once the members have returned to Cardiff in September. Additional information: 1 We note that the Welsh Government has organized similar celebrations to mark the Page contributions of two other prominent Welshmen recently. -

Arts in Education in the Schools of Wales Print Layout 1

An independent report for the Welsh Government into Arts in Education in the Schools of Wales by Professor Dai Smith September 2013 This Report is dedicated to the Memory of Professor Gareth Elwyn Jones (1939-2013) “Encapsulating many of the internal tensions and contradictions of change and development in Wales… has been education policy. At various moments in Welsh history, education has assumed an importance well beyond its normal parameters… and… since 1979, education has once more been central to discussion of Wales and Welshness” Professor Gareth Elwyn Jones Front cover: Gallery workshop at Ffotogallery (Photo Rowan Lear) Contents An independent report for the Welsh Government into Arts in Education in the Schools of Wales Preface by Professor Dai Smith 03 1. Summary of recommendations 04 Recommendations Definitions 2. The Claim of Wales: Cymru Fydd 06 Context Current practice/thinking in Wales What we can and should achieve 3. Evidence: The International perspective 15 Improved learner outcomes Role of the arts in improving literacy and numeracy, and in reducing the attainment gap Use of the arts across the curriculum Partnerships, training and support 4. Evidence from nearer home: Britain and Ireland 20 5. Arts in Education in Wales: current arrangements 24 The arts and the school curriculum for Wales ITT and CPD - how do these support the teaching of the arts? The role of the local authorities The role of the Arts Council of Wales and its funded organisations 6. Overview: Consultation key themes 33 7. Findings: analysis and recommendations 41 8. Conclusion: The case for Wales 47 Terms of reference 53 Glossary 54 Criw Celf, Ruthin Craft Centre 02 Preface This report carries with it a (good) health Much of what we learned from this Review was warning. -

Arts Council of Wales

Cyngor Celfyddydau Cymru Arts Council of Wales Thursday, 19 October 2017 Bethan Jenkins AM Chair Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay Cardiff CF99 1 NA ~'~~ `- Inquiry into non-public funding of the Arts Thank you for your invitation to meet with the Committee earlier in the month. Comparative figures for business investment During the Committee hearing, Jeremy Miles AM asked about business investment in Wales in comparison with England. In particular, he wanted to know whether the funding raised in England was disproportionate to population, or to the size of the economy. I undertook to see if I could establish whether such data existed. Having spoken to colleagues in the other UK Arts Councils, it's clear that there's no directly comparable data. This is partly because of the different remits of our various organisations — for example, Arts Council England funds museums, and Creative Scotland funds and develops the creative industries. In both cases this is in addition to the arts. This males comparisons difficult. UK-wide research used to be undertaken by Arts and Business UK. However, Arts Council England withdrew its funding for Arts and Business UK in 201 1 and the organisation ceased to operate. There has been no UK-wide research since. The possibility of reinstating a UK-wide survey is something that I'll discuss with colleagues. The last year for which UK survey data is available is 201 1. The relevance of data which is six years old is clearly questionable. However, I've included, for information, the analysis of business investment across the nations and regions contained in that research. -

Participation in the Arts

Participation in the Arts Maindee Festival (image: Rhys Webber) Inquiry by the National Assembly for Wales Communities, Equality and Local Government Committee: Participation in the Arts Written submission from the Arts Council of Wales March 2012 0 Contents 1. Introduction 2 Participation in the arts Routes to participation The value of taking part in the arts Barriers to participation Funding for participatory arts activity Arts Council funded activity 2. Participation in the Arts across Wales: the data 11 The Arts in Wales Survey 2010 The 2011 Omnibus Survey The 2011 Children’s Omnibus Survey 4. Promoting a positive approach to Equalities 20 The context Our plan of action 5. Concluding comments 22 Trends in patterns of arts participation The relationship between public funding and levels of participation The Arts Council’s Investment Review Alternative sources of funding The Arts Council and Local Government in Wales Taking action Appendices 1. Case study: Power of the Flame 27 2. Case study: Reach the Heights 28 3. Case Study: Splash Arts 29 4. Case Study: The Gwanwyn Festival for older people 31 5. Case Study: Hijinx Theatre Training Academy 32 6. About the Arts Council of Wales 33 1 1. Introduction Participation in the arts This submission focuses on the subject of this Inquiry: Participation in the Arts. Participation is different to attendance at arts events. There is, of course, some degree of ‘participation’ as an audience member. After all, the best art always draws in its audience and invokes an emotional response of some kind. However, we have spent time researching these issues and reviewing the relevant literature, and our view is informed by accepted practice in this field. -

1985 Arts Council Wales 2018-19 CONV.Indd

Arts Council of Wales Lottery Distribution Account 2018-19 HC 2524 £10.00 Arts Council of Wales Lottery Distribution Account 2018-19 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 35(5) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 (as amended by the National Lottery Act 1998) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 22 July 2019 22 July 2019 HC 2524 £10.00 The National Audit Office (NAO) helps Parliament hold government to account for the way it spends public money. It is independent of government and the civil service. The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Gareth Davies, is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO. The C&AG certifies the accounts of all government departments and many other public sector bodies. He has statutory authority to examine and report to Parliament on whether government is delivering value for money on behalf of the public, concluding on whether resources have been used efficiently, effectively and with economy. The NAO identifies ways that government can make better use of public money to improve people’s lives. It measures this impact annually. In 2018 the NAO’s work led to a positive financial impact through reduced costs, improved service delivery, or other benefits to citizens, of £539 million. © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. -

CULTURE in CARDIFF February 2020

A Short Scrutiny Report of the: Economy & Culture Scrutiny Committee CULTURE IN CARDIFF February 2020 Cardiff Council Report of the Economy & Culture Scrutiny Committee Short Scrutiny Study – Culture in Cardiff CONTENTS CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................. 2 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................ 3 TERMS OF REFERENCE ..................................................................................................................... 4 KEY FINDINGS ....................................................................................................................................... 5 RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................................................................................... 6 DEFINITIONS OF CULTURE ............................................................................................................... 7 ECONOMIC ROLE OF CULTURE ...................................................................................................... 7 PLACE-MAKING ROLE OF CULTURE ........................................................................................... 10 EXISTING LANDSCAPE ..................................................................................................................... 11 SUSTAINABLE FUTURE FOR CULTURE .....................................................................................