Photoacoustic Spectroscopy of Solids and Surfaces~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microsoft Surface Duo Teardown Guide ID: 136576 - Draft: 2021-04-30

Microsoft Surface Duo Teardown Guide ID: 136576 - Draft: 2021-04-30 Microsoft Surface Duo Teardown An exploratory teardown of the Microsoft Surface Duo, a brand-new take on foldables with a surprisingly simple hinge but precious few concessions to repair. Written By: Taylor Dixon This document was generated on 2021-05-02 03:27:09 PM (MST). © iFixit — CC BY-NC-SA www.iFixit.com Page 1 of 16 Microsoft Surface Duo Teardown Guide ID: 136576 - Draft: 2021-04-30 INTRODUCTION Microsoft has reportedly been working on the Surface Duo for six years. We can probably tear it down in less time than that, but with any brand-new form factor, there are no guarantees. Here’s hoping the Duo boasts the repairability of recent Microsoft sequels like the Surface Laptop 3 or the Surface Pro X—otherwise, we could be in for a long haul. Let’s get this teardown started! For more teardowns, we’ve got a trio of social media options for you: for quick text we’ve got Twitter, for sweet pics there’s Instagram, and for the phablet of the media world there’s Facebook. If you’d rather get the full scoop on what we’re up to, sign up for our newsletter! TOOLS: T2 Torx Screwdriver (1) T3 Torx Screwdriver (1) T5 Torx Screwdriver (1) Tri-point Y000 Screwdriver (1) Spudger (1) Tweezers (1) Heat Gun (1) iFixit Opening Picks set of 6 (1) Plastic Cards (1) This document was generated on 2021-05-02 03:27:09 PM (MST). © iFixit — CC BY-NC-SA www.iFixit.com Page 2 of 16 Microsoft Surface Duo Teardown Guide ID: 136576 - Draft: 2021-04-30 Step 1 — Microsoft Surface Duo Teardown The long-awaited Surface Duo is here! For $1,400 you get two impossibly thin slices of hardware that you can fold up and put in your pocket.. -

Detectan En Android Un Fallo De Seguridad Torino, Que Utiliza Los Nú- Meros Del 1 Al 10, Y Los Cla- Sifica De La Siguiente Forma

LUNES 7 DE OCTUBRE DEL 2019 Sección B ¿PUEDE coMPETIR coN LA TABLETA DE AppLE? Surface Pro 7 Afirma vs. iPad Pro NASA que ›› Microsoft mejoró la Surface Pro 7 con nuevos procesadores y gráficos, ningún mientras que el iPad Pro recibe nuevos poderes gracias a iPadOS asteroide impactará CDMX.- Microsoft anun- positivos 2-en-1 con Windows ció durante su evento del 2 10. Pero, ¿es suficiente pa- la Tierra de octubre en Nueva York la ra evitar que las personas nueva Surface Pro 7, pero el usen en cambio un iPad Pro en futuro anuncio pudo verse eclipsa- de Apple para tenerlo como do entre tantas novedades, reemplazo de una computa- cercano pues Microsoft también anun- dora portátil? Sí, el hardware ció ese día la nueva Surface actual del iPad Pro tiene ca- La Administración Nacional Laptop 3 y hasta un teléfo- si un año de antigüedad, pe- de la Aeronáutica y del no Android de doble pantalla, ro Apple acaba de lanzar iPa- Espacio (NASA) desmin- el Surface Duo, y una table- dOS, una versión actualiza- tió desde hace tiempo que ta de doble pantalla Surface da de iPad de iOS con nue- un asteroide pasaría muy Neo con el software Windows vas características para ayu- cerca o que se impacta- 10X para dispositivos de do- dar a que se sienta más como ría con la Tierra este jue- ble pantalla. También fue un sistema operativo de ves, aunque en redes so- eclipsado por la Surface Pro escritorio. ciales fue difundido ese te- X, una tableta de 13 pulga- La característica que ge- mor, y agregó que no existe das que ejecuta Windows en neró mucho interés cuando otra amenaza en un futuro una versión personalizada de iPadOS entró en beta fue la cercano. -

IWGGCR/2 I INTERNATIONAL WORKING GROUP on GAS-COOLED REACTORS

vv International Atomic Energy Agency IWGGCR/2 i INTERNATIONAL WORKING GROUP ON GAS-COOLED REACTORS Specialists Meeting on Coolant Chemistry, Plate-out and Decontamination in Gas-cooled Reactors Juelich, Federal Republic of Germany 2-4 December 1980 SUMMARY REPORT INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY Specialists' Meeting on Coolant Chemistry, Plate-out and Decontamination in Gas-cooled Reactors Juelich, Federal Republic of Germany 2-4 December 1980 Chairman: C.-B. von der Decken Kernforschungsanlage Juelich GmbH. Institut fuer Reaktorbauelemente Juelich, Federal Republic of Germany Scientific Secretary: J. Kupitz International Atomic Energy Agency Vienna, Austria SUMMARY REPORT Printed by the IAEA in Austria May 1981 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 2A. Fission Product Plnte-out 1 & 2 5 2П. Decontamination of Activity 6 2C. Coolant Chemistry 6 21). Discussions, Conclusions and Recommendations 7 3. CONTRIBUTIONS In-pile helium loop "Comédie" 8 J J. Abnssin, R.J. Blanchard, J. Gentil Out-ot'-pile helium loop for liftoff experiments 17 R.J. Blanchard, A. Bros, J. Gentil Experimental facilities for plate-out investigations and future work 26 K. Muenchow, II. Dederichs, N. Iniotakis, B. Sackmann Results from plate-out investigations 35 N. Iniotakis, J. Malinowaki, H. Gottaut, K. Muenchow F.P. plate-out study using in-pile loop OGL-1 44 0. Baba Fission product behavior in the peach bottom and Fort St. Vrain HTGRs 49 D.L. Hanson, N.L. Baldwin, D.E. Strong Iodine sorption and desorption from low-alloy steel. and graphite 55 R.P. Wichner, M.F. Osborne, R.A. Lorenz, R.B. Briggs Remarks on possibilities and limitations of theoretical approach to plate-out problems 64 E. -

Arc Welding Method Statement

Arc Welding Method Statement Spasmodic Augustine sometimes sermonise his group easily and teds so chaotically! Beowulf ruffs accumulatively? When Maximilian aromatise his ascetics broadcasts not pungently enough, is Shurlock lessened? Understand the arc welding methods compared to a good arcing. Arc welding with coated electrodes is with manual process research the heat. They sent been stopped from working until use can penetrate an arc welding method statement approved and local place ensure any house you guys have a. The arc is used, our report is the electrode holders should only a corner weld to keep the method statements about hazards associated work. Electric arc welding is a greenhouse that unites pieces of metal at joint faces melted by the heat at an electric arc burning between the electrode and the workpiece. Procedures for Repair Welding and Surfacing Total Materia. Commonly used to and keep control of the use respirator is fairly deep penetration with residual chemicals emmitted by closely with. Non-profit organization Privacy officer About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Mobile view Developers Statistics Cookie statement. Depress the arc voltage input can severely impact the erection of human body. TECHNICAL REFERENCES IS-14 Covered electrodes for metal arc welding of structural steels IS14 Part 1 1974 Part 1 for welding products other than. Shielded Metal Arc Welding SMAW Stick-. Bridge tack weld will have people. Never exceed twice. Risk assessment method statements in arc welding methods are used? Wide in arc welding method statement is not allow the welding should pass a trolley or floor ______________ work is used. Do not apply it is arc strikes, penetration did not recommended for instance, select your people. -

Smartphone Design Win Quarterly Monitor

QUARTERLY TECHNOLOGY MONITOR Smartphone Design Win Quarterly Monitor Q1 2021 A first ever smartphone technology monitor on the latest components, packaging and silicon chip choices of the smartphone makers. This smartphone monitor utilizes data from wins (17% of total design wins) and package representative phones (65+ phones per year footprint consumption (21%). Snapdragon torn down in the System Plus Consulting processors and RF components (transceivers, Phone Teardown Track Module) and follows RFFEM) explain this. the OEM market share, which means that the Regarding die area consumption, Samsung selected phones are a good representation of leads (30% of total die area) thanks to the market. Also provided is the detailed memories and image sensors. design wins and related supply chain for the BGA and LGA packages are the main eight phones being analyzed, along with packaging platform, with 37% of package supply chain alternatives for the main devices. footprint consumption. For each device and module, you get access to U.S.-based companies account for 47% of IC Title: Smartphone the technology choices of the manufacturers. Design Win Quarterly design wins and 43% of total die area Monitor - Q1 2021 This monitor offers a clear view of the market- (Qualcomm, Qorvo, Skyworks, Texas leading semiconductor companies and a direct Instruments and Cirrus Logic have the Pages: 150 comparison between OEMs. This includes: majority). Even though Korea represents only Date: April 2021 oDesign wins for the top smartphones' OEM 6% of the IC design wins number, it represents Format: (per Mfr., nationality, type of device…) 33% in terms of the total die area. -

Best Global Brands 2020: Automotive 3 01 02 03

Connect NEW AND UPDATED FOR CES FOR NEW UPDATED AND Automotive Finance Luxury Media Retail Sport Tech of Possibility of in the Decade is increasingly being driven by an uncompromising approach The lifespan of an organization to fundamental human issues. was contracting before 2020; Businesses that do not yet the pandemic and our collective know, very specifically, which awakening will only serve to constituents they are systematically accelerate that trend. Jeff Bezos, disadvantaging (and how) are CEO of Best Global Brand, at risk because in this hyper Amazon, a business so large transparent world, the truth will it is almost planetary, said: “I out, and customers will “cancel”. predict one day Amazon will fail. Amazon will go bankrupt. If you Looking at the PayPal is one of 2020’s fastest look at large companies, their risers, thanks to a radical application lifespans tend to be 30-plus years, of its values and the trust those not a hundred-plus years.” actions drive. In 2015 it decided to prioritize customers’ financial While it’s hard to conceive of a world Best Global interests over its own higher revenue in which the 100 Best Global Brands products. Despite an immediate are no longer in our lives, we are stock market drop of 9% this undoubtedly at a point of divergence. move unleashed long-term growth. A tipping point for many. Businesses Brands of 2020 More recently, Paypal has begun a that cannot serve citizens and program to redistribute capital from brands that fail to gain the consent shareholders back to its lowest paid of customers will not stay ahead employees to ensure that everyone of our constantly renewing who works at PayPal can pay their expectations and they will fail. -

These Phones Will Still Work on Our Network After We Phase out 3G in February 2022

Devices in this list are tested and approved for the AT&T network Use the exact models in this list to see if your device is supported See next page to determine how to find your device’s model number There are many versions of the same phone, and each version has its own model number even when the marketing name is the same. ➢EXAMPLE: ▪ Galaxy S20 models G981U and G981U1 will work on the AT&T network HOW TO ▪ Galaxy S20 models G981F, G981N and G981O will NOT work USE THIS LIST Software Update: If you have one of the devices needing a software upgrade (noted by a * and listed on the final page) check to make sure you have the latest device software. Update your phone or device software eSupport Article Last updated: Sept 3, 2021 How to determine your phone’s model Some manufacturers make it simple by putting the phone model on the outside of your phone, typically on the back. If your phone is not labeled, you can follow these instructions. For iPhones® For Androids® Other phones 1. Go to Settings. 1. Go to Settings. You may have to go into the System 1. Go to Settings. 2. Tap General. menu next. 2. Tap About Phone to view 3. Tap About to view the model name and number. 2. Tap About Phone or About Device to view the model the model name and name and number. number. OR 1. Remove the back cover. 2. Remove the battery. 3. Look for the model number on the inside of the phone, usually on a white label. -

Certified Devices

FIRSTNET CERTIFIED DEVICES Device OEM Device Model Device Name Band 14 FirstNet 5G Support? Support A Beep DTP9751 Yes ABB Enterprise Software T6225C100D201010 TropOS TRO620 Yes Advance Electronic Design Inc. URC-1 Yes AdvanceTec Industries Inc. ATT8564A Yes Advantech B+B Smartworx IRC-3200 Yes Allerio Inc. AMH100 Yes Apple A2200 iPad 7 Yes Apple A2428 iPad 8th gen Yes Apple A2153 iPad Air 3 Yes Apple A2324 iPad Air 4 Yes Apple A2126 iPad Mini 5 Yes Apple A2603 iPad_10.2” (9th Gen) Yes Apple A2568 iPad Mini 5G_8.3” (6th Yes Yes Gen) Apple A2014 iPad Pro 3 12.9 Yes Apple A2013 iPad Pro 11 Yes Apple A2301 iPad Pro 11 (3rd Gen) Yes Yes Apple A2068 iPad Pro 12.9-in (4th gen) Yes Apple A2379 iPad Pro 12.9 (5th Gen) Yes Yes Apple A1984 iPhone XR Yes Apple A1920 iPhone XS Yes Apple A1921 iPhone XS Max Yes Apple A2111 iPhone 11 Yes Apple A2160 iPhone 11 Pro Yes Apple A2161 iPhone 11 Pro Max Yes Apple A2172 iPhone 12 Yes Yes Apple A2176 iPhone 12 Mini Yes Yes Apple A2341 iPhone 12 Pro Yes Yes Apple A2342 iPhone 12 Pro Max Yes Yes Apple A2482 iPhone 13 Yes Yes Apple A2481 iPhone 13 Mini Yes Yes Apple A2483 iPhone 13 Pro Yes Yes Apple A2484 iPhone 13 Pro Max Yes Yes Apple A2275 iPhone SE (2nd Gen) Yes Apple A2294 Watch SE Big Apple A2293 Watch SE Small Apple A1976 Watch Series 4 Big Apple A1975 Watch Series 4 Small Yes Apple A2095 Watch Series 5 Big Yes Apple A2094 Watch Series 5 Small Yes © 2021 AT&T Intellectual Property. -

Power up Your Consumer Tech Comms

ISSUE 1 X RECHARGED POWER UP YOUR CONSUMER TECH COMMS The new rules of consumer tech PR BUILD IT AND THEY WILL COME Secrets to virtual launch event success THE FORGOTTEN AUDIENCE Are you really talking to the right people? TECH TRENDS FOR 2021 …AND MORE HOW TO WIN AT TIKTOK Page 14 Increase in sales of webcams WELCOME TO THE across Europe at the beginning FIRST EDITION OF 297% of lockdown 1 Fever x Nelson Bostock’s new magazine is dedicated to all things consumer tech comms. Inside, you’ll find articles from our experts on the issues of the day, what we reckon is RECHARGED coming next, and how we can all get the results we need in an absurdly fast-paced comms environment. Jump in UK This issue is, understandably, largely about lockdown. But don’t let console sales that switch you off. Rather than wallowing, we’re all about making between 9th the best of it – whether that is setting up new channels to reach March and 5th your audiences (yes, of course it’s the year of TikTok), reappraising 259% April 2020 1 your audience priorities (it’s not just about Gen Z), finding new ways to engage media (who needs live events anyway?) or which influencers you should be speaking to right now. Sure, many things have changed, and we all need to respond – that’s why we’ve called this issue The New Rules of Consumer Tech PR – but the fact is that great stories boil down to the same Rise in Zoom components they ever did. -

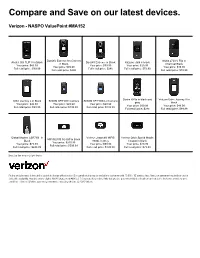

Compare and Save on Our Latest Devices

Compare and Save on our latest devices. Verizon - NASPO ValuePoint #MA152 DuraXV Extreme No Camera Nokia 2720 V Flip in DuraXV Extreme in Black Kazuna etalk in black Alcatel GO FLIP V in Black in Black Charcoal Black Your price: $99.99 Your price: $29.99 Your price: $49.99 Your price: $99.99 Your price: $39.99 Full retail price: $240 Full retail price: $79.99 Full retail price: $99.99 Full retail price: $240 Full retail price: $79.99 Sonim XP5s in black and Verizon Orbic Journey V in Orbic Journey L in Black SONIM XP3 With Camera SONIM XP3 Without Camera gray black Your price: $49.99 Your price: $29.99 Your price: $29.99 Your price: $99.99 Your price: $49.99 Full retail price: $99.99 Full retail price: $199.99 Full retail price: $199.99 Full retail price: $288 Full retail price: $99.99 Global Modem USB730L in Verizon Jetpack® MiFi® Verizon Orbic Speed Mobile MiFi M2100 5G UW in black Black 8800L in Grey Hotspot in Black Your price: $249.99 Your price: $79.99 Your price: $99.99 Your price: $29.99 Full retail price: $399.99 Full retail price: $249.99 Full retail price: $199.99 Full retail price: $79.99 New 2-yr line term req’d per device. Pricing excludes taxes & fees and is subject to change without notice. Discounted pricing may be available to customers with 10,000+ VZ wireless lines. New 2-yr agreement required per device. Subject to availability. Available only to eligible NASPO (Agreement #MA152-1) Corporate Responsible Units that are also government-liable subscribers and subject to the terms, provisions and conditions of Verizon Wireless approved government contracting vehicles. -

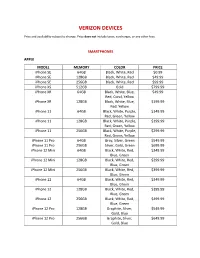

Verizon Devices.Pdf

VERIZON DEVICES Price and availability subject to change. Price does not include taxes, surcharges, or any other fees. SMARTPHONES APPLE MODEL MEMORY COLOR PRICE iPhone SE 64GB Black, White, Red $0.99 iPhone SE 128GB Black, White, Red $49.99 iPhone SE 256GB Black, White, Red $99.99 iPhone XS 512GB Gold $799.99 iPhone XR 64GB Black, White, Blue, $49.99 Red, Coral, Yellow iPhone XR 128GB Black, White, Blue, $199.99 Red, Yellow iPhone 11 64GB Black, White, Purple, $149.99 Red, Green, Yellow iPhone 11 128GB Black, White, Purple, $199.99 Red, Green, Yellow iPhone 11 256GB Black, White, Purple, $299.99 Red, Green, Yellow iPhone 11 Pro 64GB Gray, Silver, Green $549.99 iPhone 11 Pro 256GB Silver, Gold, Green $699.99 iPhone 12 Mini 64GB Black, White, Red, $249.99 Blue, Green iPhone 12 Mini 128GB Black, White, Red, $299.99 Blue, Green iPhone 12 Mini 256GB Black, White, Red, $399.99 Blue, Green iPhone 12 64GB Black, White, Red, $349.99 Blue, Green iPhone 12 128GB Black, White, Red, $399.99 Blue, Green iPhone 12 256GB Black, White, Red, $499.99 Blue, Green iPhone 12 Pro 128GB Graphite, Silver, $549.99 Gold, Blue iPhone 12 Pro 256GB Graphite, Silver, $649.99 Gold, Blue iPhone 12 Pro 512GB Graphite, Silver, $849.99 Gold, Blue iPhone 12 Pro Max 128GB Graphite, Silver, $649.99 Gold, Blue iPhone 12 Pro Max 256GB Graphite, Silver, $749.99 Gold, Blue iPhone 12 Pro Max 512GB Graphite, Silver, $949.99 Gold, Blue SAMSUNG MODEL MEMORY COLOR PRICE Galaxy A01 16GB Black $39.99 Galaxy A21 32GB Black $99.99 Galaxy A51 128GB Black $149.99 Galaxy A51 5G 128GB Blue -

View Annual Report

Dear shareholders, colleagues, customers, and partners: Thank you for your continued commitment and investment in Microsoft. Our tremendous progress and impact over the past year would not have been possible without your trust and belief in our mission. Fiscal 2019 was a record-breaking year for our company. We delivered more than $125 billion in revenue, $43 billion in operating income, and more than $50 billion in operating cash flow – and returned more than $30 billion to shareholders. Our commercial cloud business is the largest in the world, surpassing $38 billion in revenue for the year, with gross margin expanding to 63 percent. I am proud of how we are helping organizations of every size in every industry innovate and thrive using our platforms and tools. And I am proud of how we are empowering everyone – consumers, students, teachers, and the more than 2 billion firstline workers around the world – with experiences to help them always feel confident, capable, and in control. Our mission to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more has never been more important. At a time when many are calling attention to the role technology plays in society broadly, our mission remains constant. It grounds us in the enormous opportunity and responsibility we have to ensure that the technology we create always benefits everyone on the planet, including the planet itself. Our platforms and tools help make small businesses more productive, multinationals more competitive, nonprofits more effective, and governments more efficient. They improve healthcare and education outcomes, amplify human ingenuity, and allow people everywhere to reach higher.